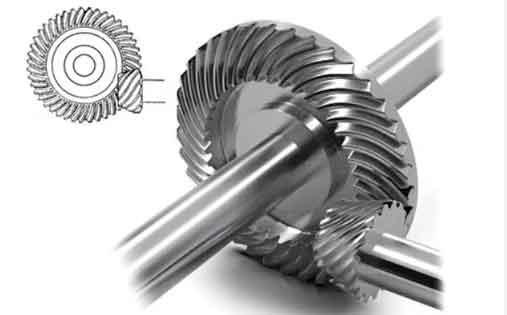

In recent years, we have witnessed remarkable progress in the design and manufacturing of spiral bevel gears and hypoid gears, driven by advancements in computational technology, information science, and fundamental engineering principles. These gears are critical components in various mechanical transmission systems, particularly in automotive, aerospace, and industrial machinery, where demands for high speed, heavy load capacity, and lightweight construction are ever-increasing. The tooth surface geometry of spiral bevel gears is inherently tied to the machining processes, with traditional systems like Gleason, Klingelnberg, and Oerlikon dominating the landscape. Among these, the Gleason system remains the most widely adopted, and thus, our discussion will primarily focus on its methodologies and evolution. This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state-of-the-art in design, contact performance analysis, manufacturing technologies, and dynamics of spiral bevel gears, while also outlining future research directions. We will incorporate tables and mathematical formulations to summarize key concepts, enhancing clarity and depth.

The development of spiral bevel gears hinges on precise tooth surface generation and optimization to ensure efficient power transmission, minimal noise, and reduced vibration. We observe that modern approaches have shifted from empirical methods to analytical and computational techniques, enabling better control over gear performance. In this review, we delve into the intricacies of design and contact analysis, manufacturing innovations, dynamic behavior, and prospective research areas, all from a first-person perspective as researchers and engineers engaged in this field. The integration of computer-aided design (CAD), finite element analysis (FEA), and computer numerical control (CNC) machining has revolutionized how we approach spiral bevel gears, making it possible to achieve higher accuracy and reliability.

Design and Contact Analysis Research Status

Traditionally, the Gleason technique has been the cornerstone for designing spiral bevel gears, based on the “local conjugation principle.” This method involves cutting the gear tooth surface first, then selecting a reference point to determine first- and second-order contact parameters such as position, normal vector, and normal curvature for the pinion tooth surface that achieves line contact with the gear. The key challenge lies in modifying the normal curvature at the reference point to derive machining adjustment parameters, which often requires iterative trial-and-error and extensive experience. Mathematically, this can be expressed using differential geometry. For instance, the tooth surface equation for a spiral bevel gear can be represented as:

$$ \mathbf{r}(u, v) = [x(u, v), y(u, v), z(u, v)] $$

where \( u \) and \( v \) are parameters defining the surface. The normal curvature \( \kappa_n \) at a point is given by:

$$ \kappa_n = \frac{L du^2 + 2M du dv + N dv^2}{E du^2 + 2F du dv + G dv^2} $$

Here, \( E, F, G \) are the first fundamental form coefficients, and \( L, M, N \) are the second fundamental form coefficients. The Gleason method adjusts these coefficients to achieve desired contact patterns, but it offers limited control over higher-order parameters.

To address these limitations, the local synthesis method was introduced. This approach specifies the direction of the contact path, the rate of change of transmission ratio, and the length of the instantaneous contact ellipse’s major axis at the reference point. Using differential geometry, we derive the principal curvatures and directions for the pinion tooth surface, enabling effective pre-control of meshing performance near the reference point. The local synthesis method optimizes second-order contact parameters, but it does not account for higher-order effects, which can lead to issues like severe curvature of the contact path or rapid changes in ellipse dimensions, resulting in undesirable contact patterns such as rhombic, fishtail, or trapezoidal shapes.

The third-order contact analysis theory extends this by employing mathematical tools like curvature tensors and moving frames. This framework allows us to compute not only instantaneous transmission ratios, accelerations, and contact ellipse shapes but also higher-order accelerations and geodesic curvature of the contact path. By optimizing third-order contact parameters using redundant machine settings, we can achieve improved contact performance throughout the meshing cycle. The governing equations for third-order analysis involve Taylor expansions of the tooth surface equations. For example, the deviation from the reference point can be expressed as:

$$ \Delta \mathbf{r} = \frac{1}{2} \mathbf{r}_{uu} \Delta u^2 + \mathbf{r}_{uv} \Delta u \Delta v + \frac{1}{2} \mathbf{r}_{vv} \Delta v^2 + \text{higher-order terms} $$

where subscripts denote partial derivatives. This method provides a comprehensive tool for designing high-quality point-contact conjugate tooth surfaces for spiral bevel gears.

In terms of tooth profile design, the concept of non-zero displacement has been proposed, breaking away from traditional height modifications. This allows flexible selection of displacement coefficients based on meshing performance requirements, facilitating optimization for low noise and high load capacity. The displacement coefficients \( x_1 \) and \( x_2 \) for gear and pinion can be optimized using objective functions such as minimizing transmission error or maximizing contact ratio. A table summarizing different design methods and their key features is presented below:

| Design Method | Key Parameters Controlled | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Gleason | First- and second-order contact parameters | Widely used, empirical reliability | Iterative, requires experience |

| Local Synthesis | Contact path direction, transmission ratio change rate, ellipse axis length | Pre-control near reference point | No control over higher-order effects |

| Third-Order Analysis | Up to third-order contact parameters | Comprehensive performance control | Computationally intensive |

| Non-Zero Displacement | Displacement coefficients | Flexible optimization | Dependent on manufacturing constraints |

Another innovative approach is the active design method based on functional requirements, which directly designs the contact path, instantaneous contact ellipse dimensions, and higher-order accelerations during meshing. This enables the generation of various transmission error curves with desired shapes and variations, offering a holistic description of tooth surface behavior. However, this method requires Free-form gear machining centers for implementation. The mathematical formulation for active design involves solving inverse problems to derive tooth surface coordinates from specified contact conditions. For instance, given a desired transmission error function \( \Delta \phi(\theta) \), we can solve for the tooth surface modifications.

High-tooth spiral bevel gears have also been explored to increase the contact ratio, thereby enhancing meshing smoothness and load capacity. The design based on transmission error for high contact ratio spiral bevel gears aims to maximize actual contact ratio by optimizing tooth surface geometry, reducing internal excitations, and minimizing vibration and noise. The contact ratio \( \epsilon \) can be calculated as:

$$ \epsilon = \frac{\text{Length of contact path}}{\text{Base pitch}} $$

By expanding the contact area through careful design, we can achieve values of \( \epsilon \) greater than 2, significantly improving performance.

Recent advancements in tooth contact analysis (TCA) have leveraged finite element methods for loaded contact analysis. This allows us to obtain loaded transmission error curves and actual contact ratios under operational conditions. The finite element formulation for contact between spiral bevel gears involves solving the equilibrium equations:

$$ \mathbf{K} \mathbf{u} = \mathbf{F} $$

where \( \mathbf{K} \) is the stiffness matrix, \( \mathbf{u} \) is the displacement vector, and \( \mathbf{F} \) is the load vector. Contact constraints are applied using penalty methods or Lagrange multipliers. Additionally, concepts like equivalent load adjustment values and transmission angle displacement coordination have been introduced to improve loaded contact analysis accuracy.

In scenarios with manufacturing errors and deformations, elastic contact analysis methods have been developed. By decomposing elastic deformations into support, body, and contact components, we can predict changes in geometric quantities and establish contact conditions for elastic tooth surfaces. This leads to active design methods that ensure expected loaded contact performance from the initial design stage. The edge contact problem has been addressed using vector cross-products between tooth surface normals and top cone normals to define edge curves, enabling more accurate TCA and loaded tooth contact analysis (LTCA). Integrating local synthesis, TCA, and LTCA into a closed-loop optimization framework represents a novel approach for refining spiral bevel gear designs.

Furthermore, real tooth surface deviations due to machining errors and heat treatment distortions are critical research topics. Real tooth surfaces can be modeled as the sum of a theoretical surface function and a deviation function, measured using CNC coordinate measuring machines. Spline functions, such as bicubic cylindrical splines, approximate the deviation, facilitating TCA for real surfaces. This allows compensation during cutting by transferring gear errors to the pinion tooth surface.

Modern Manufacturing Technology Overview

The manufacturing of spiral bevel gears is closely linked to advancements in machine tools. Historically, the introduction of tool tilt methods marked a significant breakthrough, and with the addition of变性机构, machining techniques became more sophisticated. However, the advent of CNC technology has transformed the landscape, particularly with Free-form gear machining centers that offer unprecedented flexibility in tooth surface generation. These centers can realize arbitrary relative motions between the cutter and workpiece, enabling the implementation of advanced design theories.

For instance, methods have been developed to emulate traditional cradle-type machine motions on Free-form CNC machines through equivalent transformations. The basic theory for cutting on five-axis CNC gear machines involves determining machining parameters from tooth surface design parameters. The mathematical model for generating tooth surfaces on such machines can be expressed as:

$$ \mathbf{T}_{\text{workpiece}} = \mathbf{T}_{\text{cutter}} \cdot \mathbf{R}(\theta) \cdot \mathbf{T}_{\text{offset}} $$

where \( \mathbf{T} \) denotes transformation matrices, \( \mathbf{R} \) is a rotation matrix, and \( \theta \) is the workpiece rotation angle. This allows precise control over cutter position and orientation.

Moreover, research has focused on implementing spiral bevel gear machining on universal five-axis CNC machines. By converting traditional adjustment parameters into NC motion parameters through coordinate transformations, we can achieve relative motions between tool and workpiece. This democratizes high-quality gear manufacturing, making it accessible without specialized gear cutters. A comparison of manufacturing technologies is summarized in the table below:

| Manufacturing Technology | Key Features | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Cradle Machines | Mechanical adjustments, tool tilt | Proven reliability | Limited flexibility, skill-dependent |

| Free-Form CNC Machines | Five-axis联动, arbitrary motions | High flexibility, precise control | High cost, complex programming |

| Universal Five-Axis CNC | Conversion of traditional parameters | Cost-effective, versatile | Requires software integration |

The integration of CAD/CAM systems with CNC machines has streamlined the production of spiral bevel gears, allowing for rapid prototyping and customization. We emphasize that the design and manufacturing of spiral bevel gears are increasingly becoming digital, with simulation-driven approaches reducing physical trials.

Dynamics of Spiral Bevel Gears

As spiral bevel gears trend towards higher speeds and lighter weights, dynamic issues like vibration and noise have become prominent. Dynamic load calculations for hypoid gears have been developed, considering time-varying meshing stiffness and transmission errors. The nonlinear dynamics of spiral bevel gear systems can be modeled using single-degree-of-freedom equations:

$$ m \ddot{x} + c \dot{x} + k(t) x = F(t) $$

where \( m \) is the equivalent mass, \( c \) is the damping coefficient, \( k(t) \) is the time-varying meshing stiffness, and \( F(t) \) is the external excitation. The meshing stiffness \( k(t) \) varies with tooth contact conditions and can be derived from LTCA results.

Studies have established nonlinear dynamic equations for spiral bevel gear systems, solving for frequency response curves, phase diagrams, time histories, and dynamic loads. The influence of pre-control parameters from local synthesis on system vibration has been investigated, highlighting the importance of integrating geometric design with dynamic analysis. For instance, optimizing tooth surface modifications can reduce transmission error fluctuations, thereby mitigating vibrations. The equation for nonlinear vibration with backlash can be expressed as:

$$ \ddot{\theta} + 2 \zeta \omega_n \dot{\theta} + \omega_n^2 \theta + \gamma \theta^3 = \epsilon \cos(\Omega t) $$

where \( \theta \) is the angular displacement, \( \zeta \) is the damping ratio, \( \omega_n \) is the natural frequency, \( \gamma \) is the nonlinear coefficient, and \( \epsilon \) and \( \Omega \) are excitation amplitude and frequency, respectively. Numerical methods like shooting and parameterization are used to find periodic solutions.

We note that dynamic analysis is crucial for ensuring the reliability and quiet operation of spiral bevel gears in demanding applications. Future work should focus on coupled multi-body dynamics models that account for housing flexibility and lubrication effects.

Research Prospects

Based on our review, we propose several directions for future research in spiral bevel gears and hypoid gears. First, there is a need to develop integrated design methodologies that combine tooth surface geometry, mechanical stress analysis, and system dynamics. Such holistic approaches would simultaneously address geometric precision, load capacity, and vibration suppression, leading to optimal performance. This could involve multi-objective optimization frameworks using algorithms like genetic algorithms or particle swarm optimization.

Second, we advocate for the establishment of a modern system integrating computers, CNC gear machines, and CNC coordinate measuring machines into a seamless design-manufacture-inspection loop. This digital thread would enable real-time feedback and adaptive manufacturing, reducing errors and improving quality. For example, in-process measurement data could be used to update cutting parameters dynamically.

Third, considering the current industrial practices, optimizing tooth surface mismatch to achieve higher-order transmission error curves for noise reduction is essential. This involves fine-tuning the mismatch amount \( \Delta \Sigma \) between gear and pinion tooth surfaces to control contact patterns under load. The mismatch can be expressed as:

$$ \Delta \Sigma = \kappa_{p} – \kappa_{g} $$

where \( \kappa_{p} \) and \( \kappa_{g} \) are the curvatures of pinion and gear surfaces, respectively. By optimizing \( \Delta \Sigma \), we can design transmission error curves with parabolic or cubic shapes that are less sensitive to misalignments.

Fourth, developing theories and methods for manufacturing spiral bevel gears on universal five-axis CNC machines is crucial for wider adoption. This includes creating post-processors and simulation tools to convert design parameters into NC code, ensuring that high-quality gears with excellent contact performance and low noise can be produced cost-effectively.

Fifth, optimizing the design of high-contact-ratio spiral bevel gears requires careful selection of contact path direction, instantaneous contact ellipse dimensions, and first- and second-derivatives of transmission ratio. The goal is to maximize actual contact ratio while minimizing sensitivity to installation and manufacturing errors. This can be formulated as an optimization problem:

$$ \text{Minimize } f(\mathbf{x}) = w_1 \cdot \text{sensitivity} + w_2 \cdot (1/\epsilon) $$

subject to constraints on contact stress and tooth strength, where \( \mathbf{x} \) includes design variables like pressure angle and spiral angle, and \( w_1, w_2 \) are weighting factors.

In conclusion, the field of spiral bevel gears is evolving rapidly, with interdisciplinary approaches bridging design, manufacturing, and dynamics. We believe that continued innovation in computational tools, materials, and processes will further enhance the performance and applications of spiral bevel gears. Our perspective underscores the importance of collaborative research between academia and industry to translate theoretical advances into practical solutions, ensuring that spiral bevel gears meet the challenges of modern engineering systems.