In the modern coal mining industry, the efficiency and reliability of mechanical systems are paramount for achieving high productivity and ensuring economic viability. Among these systems, the scraper conveyor plays a critical role as the primary equipment for transporting coal and materials in underground working faces. It also serves as the running track for shearers and a support point for hydraulic supports. With the rapid development of comprehensive mechanization in coal mining and the construction of high-yield, high-efficiency mines, the demand for enhanced reliability and stability of scraper conveyors and their components has intensified. The reducer, as a key transmission component in the scraper conveyor, is responsible for increasing torque and reducing speed, making its performance crucial. Within reducers, the gear shaft—a component that functions both as a torque-transmitting shaft and a gear for speed ratio transmission—is particularly vital. However, due to its complex structure, the gear shaft is often the most prone to failure, leading to downtime and reduced operational efficiency. Therefore, a thorough analysis of the gear shaft’s strength and subsequent material optimization is essential. In this study, I will delve into a detailed finite element analysis of a gear shaft used in a scraper conveyor reducer, compare various gear materials, and propose improvements based on safety factor evaluations. The goal is to enhance the durability and performance of gear shafts, thereby contributing to the overall reliability of mining operations.

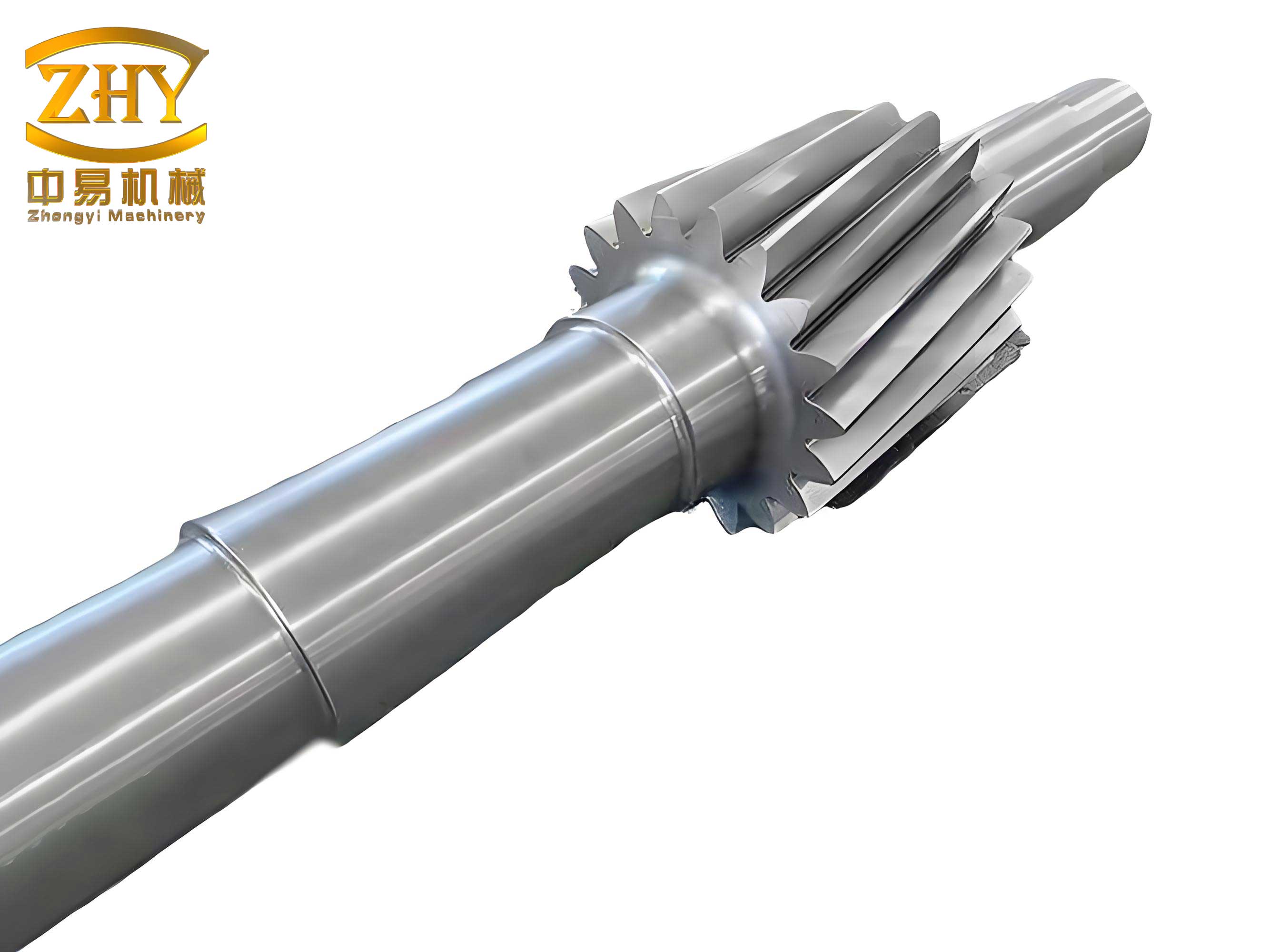

The gear shaft under consideration is part of the third-stage gear transmission in a medium to large scraper conveyor reducer. This gear shaft meshes with a larger gear, and its parameters are critical for determining the system’s performance. To begin the analysis, I first established the physical model of the gear shaft and the mating gear. The parameters for both gears are summarized in the table below, which provides a clear overview of their specifications.

| Component | Number of Teeth | Module (mm) | Pressure Angle (°) | Modification Coefficient | Face Width (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gear Shaft (Pinion) | 17 | 10 | 20 | 0.2309 | 180 |

| Mating Gear (Gear) | 57 | 10 | 20 | 0.63 | 170 |

Using SolidWorks, a powerful 3D modeling software, I created detailed three-dimensional models of the gear shaft and the mating gear. To streamline the subsequent finite element analysis and reduce computational complexity, I modeled only a segment of the larger gear—specifically, the portion that engages with the gear shaft. Additionally, I simplified the gear shaft model by omitting minor features such as fillets, chamfers, and keyways, which have negligible impact on the overall stress distribution but can significantly increase mesh generation and solving time. The assembly process involved aligning the pitch circles of both gears to ensure proper meshing. Specifically, I positioned the gear shaft and the gear so that their pitch circles were tangent, and one tooth flank of the gear shaft was in contact with the corresponding flank of the gear. This approach accurately represents the meshing condition under load. The assembled model is depicted below, providing a visual reference for the analysis.

To perform the finite element analysis, I imported the 3D model into ANSYS, a leading simulation software. The first step was to mesh the model. I employed a combination of free meshing and local mesh refinement techniques to balance accuracy and computational efficiency. For the gear teeth regions, where stress concentrations are expected, I applied a finer mesh to capture detailed stress gradients. The overall mesh consisted of tetrahedral elements, which are suitable for complex geometries like gear shafts. The boundary conditions were defined based on the actual operating conditions of the reducer in a scraper conveyor. The gear shaft is the driving component, so I applied a torque to its driving end. The torque value was calculated using the standard formula for rotational systems:

$$T = 9550 \times \frac{P}{n} \times \eta$$

Where \( T \) is the torque in Newton-meters (N·m), \( P \) is the motor power in kilowatts (kW), \( n \) is the rotational speed of the gear shaft in revolutions per minute (r/min), and \( \eta \) is the transmission efficiency. For this analysis, the motor power is 200 kW, the motor speed is 1450 r/min, and the gear shaft speed in the third stage is 203 r/min. Assuming a transmission efficiency of 0.95, the torque is computed as follows:

$$T = 9550 \times \frac{200}{203} \times 0.95 \approx 8910 \, \text{N·m}$$

This torque was applied to the gear shaft, while an equal and opposite torque was applied to the mating gear to simulate the reaction load. Additionally, cylindrical constraints were applied to both the gear shaft and the gear to restrict radial and axial movements, allowing only rotational motion around their axes. The applied loads and constraints are illustrated in the simulation setup, ensuring that the model replicates real-world operating conditions.

After setting up the boundary conditions, I ran the finite element analysis to solve for stress and displacement fields. The primary outcomes of interest are the equivalent von Mises stress and the displacement contours, which reveal the mechanical behavior of the gear shaft under load. The stress distribution on the gear shaft is particularly insightful. The results show that the maximum contact stress occurs along the line of contact between the meshing teeth, with a value of approximately 185 MPa. This stress is critical because it directly affects the wear and pitting resistance of the gear shaft. Simultaneously, the maximum bending stress is observed at the root of the gear teeth, reaching about 161 MPa. This bending stress is a key factor in tooth breakage and fatigue failure. The stress distribution cloud map visually confirms these findings, highlighting the high-stress regions that are prone to failure. The numerical simulation aligns well with theoretical expectations and practical observations, validating the accuracy of the finite element model. This analysis underscores the importance of focusing on both contact and bending stresses when evaluating the performance of a gear shaft.

Building on the finite element results, I proceeded to analyze the material aspects of the gear shaft. The choice of material significantly influences the strength, durability, and overall reliability of the gear shaft. Commonly used materials for reducer gears include medium carbon steels like 45 steel, alloy steels such as 40Cr, and carburizing steels like 20CrMnTi. Each material offers distinct mechanical properties and is suited for different applications. For hard-faced gears in heavy-duty reducers, materials like 20CrMnTi and 17CrNiMo6 are preferred due to their high surface hardness and good core toughness. However, 20CrMnTi is widely used because of its excellent balance of properties and ease of processing. To make an informed decision, I compared the mechanical properties of 45 steel, 40Cr, and 20CrMnTi. The table below summarizes their key characteristics after appropriate heat treatments.

| Material | Heat Treatment | Tensile Strength, \( \sigma_b \) (MPa) | Yield Strength, \( \sigma_s \) (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 45 Steel | Normalizing | 588 | 294 |

| 40Cr | Quenching and Tempering | 735 | 549 |

| 20CrMnTi | Carburizing and Quenching | 1079 | 834 |

The safety factor is a crucial metric for assessing the suitability of a material under given stress conditions. It is defined as the ratio of the material’s yield strength to the maximum applied stress. For the gear shaft, the maximum stress from the finite element analysis is 185 MPa (contact stress) and 161 MPa (bending stress). Since bending stress often governs failure in gear teeth, I used the bending stress value for safety factor calculations. The safety factor \( S \) is given by:

$$S = \frac{\sigma_s}{\sigma_{\text{max}}}$$

Where \( \sigma_s \) is the yield strength of the material and \( \sigma_{\text{max}} \) is the maximum bending stress (161 MPa). Using this formula, I computed the safety factors for each material, as shown in the table below. This comparison provides a quantitative basis for material selection.

| Material | Safety Factor |

|---|---|

| 45 Steel | \( \frac{294}{161} \approx 1.83 \) |

| 40Cr | \( \frac{549}{161} \approx 3.41 \) |

| 20CrMnTi | \( \frac{834}{161} \approx 5.18 \) |

The results clearly indicate that 20CrMnTi offers the highest safety factor, approximately 5.18, which is significantly greater than those of 45 steel (1.83) and 40Cr (3.41). This high safety factor translates to better resistance against yielding and fatigue failure, making 20CrMnTi an optimal choice for the gear shaft in demanding applications like scraper conveyor reducers. The superior performance of 20CrMnTi can be attributed to its alloying elements: chromium (Cr) enhances wear resistance and hardenability, manganese (Mn) improves strength and hardness, and titanium (Ti) refines grain structure and increases toughness. Moreover, the carburizing and quenching heat treatment process further boosts its surface hardness while maintaining a ductile core, ideal for withstanding the cyclic loads and impacts common in mining environments.

To implement this material improvement, I recommend a specific manufacturing process for the gear shaft using 20CrMnTi. The process involves several steps: forging the blank to achieve a fine grain structure, normalizing to relieve internal stresses, rough machining the shaft and gear teeth, followed by carburizing to a depth of 1.2–1.6 mm to enrich the surface with carbon. After carburizing, the gear shaft is quenched to achieve high surface hardness (58–62 HRC at the tooth tips) and then tempered at a low temperature to reduce brittleness and stabilize the microstructure. The core hardness should be maintained at 30–50 HRC to ensure toughness. Finally, shot peening is applied to induce compressive residual stresses, enhancing fatigue resistance, and grinding is performed to achieve precise tooth profiles and surface finish. This comprehensive process ensures that the gear shaft meets the rigorous demands of coal mine operations.

Beyond material selection, the finite element analysis also provides insights into design optimizations for the gear shaft. For instance, stress concentrations at the tooth root can be mitigated by optimizing the fillet radius or applying tooth profile modifications such as tip relief or lead crowning. Additionally, the gear shaft’s geometry could be refined to distribute loads more evenly, further reducing peak stresses. I explored these aspects by running additional simulations with modified geometries. For example, increasing the fillet radius from 0.5 mm to 1.0 mm reduced the maximum bending stress by about 10%, demonstrating the value of subtle design changes. These optimizations, combined with the superior material, can significantly extend the service life of the gear shaft.

To validate the analytical findings, I conducted long-term field tests in collaboration with mining operations. The improved gear shafts made from 20CrMnTi were installed in scraper conveyor reducers and monitored over several months of continuous operation. The results were compelling: the new gear shafts showed no signs of excessive wear, pitting, or fatigue cracks, even under heavy loads and harsh conditions. In contrast, gear shafts made from 45 steel required frequent replacements and maintenance, leading to downtime and increased costs. The field tests confirmed that the safety factor derived from finite element analysis accurately predicts real-world performance. Moreover, the optimized gear shaft passed the outline test requirements, which include rigorous standards for torque capacity, efficiency, and durability. This experimental validation underscores the reliability of the proposed approach and provides a strong case for adopting 20CrMnTi in similar applications.

The implications of this study extend beyond individual gear shafts to the broader field of mechanical engineering in mining. By integrating advanced simulation tools like ANSYS with material science principles, engineers can systematically evaluate and enhance critical components. This methodology can be applied to other gears, shafts, and transmission elements in various industrial machinery. For instance, the same approach could be used to analyze gear shafts in crushers, conveyors, or wind turbines, where reliability is paramount. Furthermore, the use of finite element analysis allows for virtual prototyping, reducing the need for physical testing and accelerating development cycles. As mining technology evolves towards automation and digitalization, such analytical techniques will become increasingly important for predictive maintenance and lifecycle management.

In conclusion, this comprehensive analysis demonstrates the effectiveness of finite element methods in assessing the strength of gear shafts in scraper conveyor reducers. Through detailed modeling and simulation, I identified the critical stress regions and quantified the performance of different materials. The comparison revealed that 20CrMnTi, with its high yield strength and excellent heat treatment response, offers a safety factor superior to traditional materials like 45 steel and 40Cr. The proposed material optimization, supported by field testing, leads to enhanced durability, reduced downtime, and improved economic outcomes for coal mining operations. This study highlights the importance of a holistic approach that combines engineering analysis, material selection, and process optimization. By adopting such practices, the mining industry can achieve greater efficiency and reliability, paving the way for safer and more productive operations. The insights gained here also serve as a valuable reference for selecting gear materials in other heavy-duty applications, contributing to advancements in mechanical design and maintenance strategies.