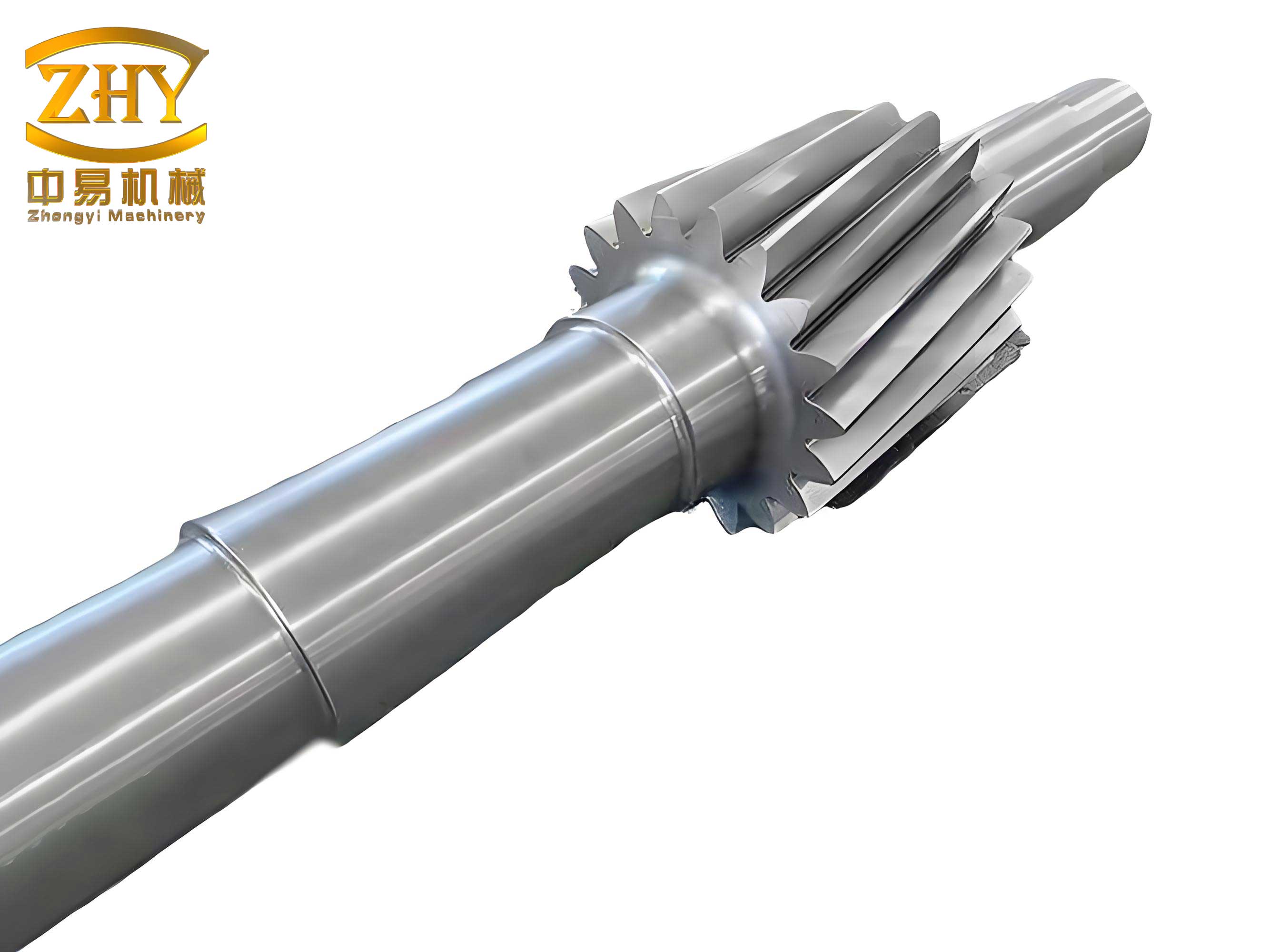

In the design of heavy-duty industrial machinery such as ball mills, the connection between the gear shaft and other components is a critical aspect that directly impacts performance, reliability, and safety. As an engineer focused on mechanical design, I often encounter challenges in selecting the optimal connection method for transmitting high torque under dynamic loads. This article delves into the detailed process of determining the connection between a ball mill’s pinion gear shaft and a semi-coupling, emphasizing the interplay between keyed and interference fits. Through rigorous analysis, calculations, and practical insights, I aim to provide a comprehensive guide that can be applied to similar design scenarios. The gear shaft, being a central element in power transmission, requires meticulous attention to ensure it can withstand operational stresses without failure.

The ball mill in question is driven by a variable-frequency motor with a power rating of 1500 kW and a speed of 200 r/min. This motor connects to the pinion gear shaft via a coupling, and the connection must reliably transmit substantial torque while accommodating shock loads inherent in milling operations. The gear shaft is made of 35CrMo steel, while the semi-coupling is constructed from 45# steel. The interface involves a nominal diameter of 275 mm and an effective engagement length of 320 mm. Given the diameter-to-length ratio of approximately 0.86, this qualifies as a short connection, which poses unique design considerations due to potential stress concentrations and alignment issues. My goal was to evaluate and select a connection method that ensures efficient torque transmission without compromising structural integrity.

Initially, I considered using a standard parallel key connection due to its simplicity and ease of assembly. For a shaft diameter of 275 mm, referring to mechanical design handbooks, a key with nominal dimensions of 63 mm in width and 32 mm in height was selected. The shaft segment length is 332 mm, allowing for a key length of 300 mm in an A-type configuration to maximize load-bearing capacity. The torque to be transmitted is calculated as follows: $$T = 9549 \times \frac{P}{n} = 9549 \times \frac{1500}{200} = 71,617.5 \, \text{Nm} \approx 71.62 \, \text{kNm}$$ where \(P\) is power in kW and \(n\) is speed in r/min. To assess the key’s suitability, I performed strength checks for compressive and shear stresses. The compressive stress on the key is given by: $$p = \frac{2T}{d_f \cdot k \cdot l} \leq \sigma_{pp}$$ where \(d_f = 275 \, \text{mm}\) is the shaft diameter, \(k = 0.5h = 16 \, \text{mm}\) is the effective key height, and \(l = L – b = 300 – 63 = 237 \, \text{mm}\) is the working length. The allowable compressive stress \(\sigma_{pp}\) is 60 MPa for the materials used. Substituting the values: $$p = \frac{2 \times 71.62 \times 10^6}{275 \times 16 \times 237} = 137.36 \, \text{MPa}$$ This exceeds the allowable limit, indicating that the key alone would fail under compressive loads. Similarly, the shear stress is calculated as: $$\tau = \frac{2T}{d_f \cdot b \cdot l} \leq \tau_p$$ with an allowable shear stress \(\tau_p = 60 \, \text{MPa}\): $$\tau = \frac{2 \times 71.62 \times 10^6}{275 \times 63 \times 237} = 34.89 \, \text{MPa}$$ While the shear stress is within limits, the compressive stress is critical. Even with a double-key arrangement (assuming 1.5 keys effective), the compressive stress reduces to \(137.36 / 1.5 = 91.57 \, \text{MPa}\), still above the allowable value. Thus, a keyed connection alone is insufficient for this gear shaft application, necessitating an alternative or combined approach.

Given the limitations of keyed connections, I explored interference fits as a viable method for torque transmission. Interference fits rely on frictional forces generated by radial pressure between the gear shaft and coupling, offering high torque capacity and improved alignment. For this critical connection, where disassembly might be required for maintenance, I selected an H7/r6 fit—a transition fit with moderate interference. This choice balances manufacturability and precision, with the hole tolerance at IT7 grade and the shaft at IT6 grade. According to standard tables, the nominal diameter of 275 mm for H7/r6 yields a minimum interference of \([\delta_{\text{min}}] = 0.042 \, \text{mm}\) and a maximum interference of \([\delta_{\text{max}}] = 0.126 \, \text{mm}\). To evaluate the feasibility, I calculated the minimum contact pressure required to transmit the torque: $$p_{f,\text{min}} = \frac{2T}{\pi d_f^2 l_f \mu}$$ where \(l_f = 320 \, \text{mm}\) is the engagement length and \(\mu = 0.14\) is the coefficient of friction for a heated assembly process. Substituting values: $$p_{f,\text{min}} = \frac{2 \times 71.62 \times 10^6}{\pi \times 275^2 \times 320 \times 0.14} = 13.46 \, \text{MPa}$$ The minimum effective interference needed to generate this pressure is derived from elastic theory: $$\delta_{e,\text{min}} = p_{f,\text{min}} d_f \left( \frac{C_a}{E_a} + \frac{C_i}{E_i} \right)$$ Here, \(E_a = 200 \, \text{GPa}\) and \(E_i = 230 \, \text{GPa}\) are the elastic moduli of the semi-coupling (45# steel) and gear shaft (35CrMo), respectively. The rigidity coefficients are calculated as: $$C_a = \frac{1 + (d_f / d_a)^2}{1 – (d_f / d_a)^2} + \nu_a \quad \text{and} \quad C_i = \frac{1 + (d_i / d_f)^2}{1 – (d_i / d_f)^2} – \nu_i$$ where \(d_a = 450 \, \text{mm}\) is the outer diameter of the coupling, \(d_i = 0 \, \text{mm}\) (solid shaft), and Poisson’s ratios are \(\nu_a = 0.3\) and \(\nu_i = 0.31\). Thus: $$C_a = \frac{1 + (275/450)^2}{1 – (275/450)^2} + 0.3 = 2.49, \quad C_i = \frac{1 + 0}{1 – 0} – 0.31 = 0.69$$ Plugging into the equation: $$\delta_{e,\text{min}} = 13.46 \times 275 \times \left( \frac{2.49}{200 \times 10^3} + \frac{0.69}{230 \times 10^3} \right) = 0.0572 \, \text{mm}$$ This exceeds the minimum available interference of 0.042 mm, suggesting that the interference fit alone may not reliably transmit the torque. To check the upper limit, I computed the maximum allowable pressure based on material yield strengths. For the semi-coupling, the yield strength \(\sigma_{sa} = 345 \, \text{MPa}\), and for the gear shaft, \(\sigma_{si} = 390 \, \text{MPa}\). The maximum pressures are: $$p_{fa,\text{max}} = \frac{1 – (d_f / d_a)^2}{\sqrt{3 + (d_f / d_a)^2}} \sigma_{sa} = \frac{1 – (275/450)^2}{\sqrt{3 + (275/450)^2}} \times 345 = 117.69 \, \text{MPa}$$ $$p_{fi,\text{max}} = \frac{1 – (d_i / d_f)^2}{2} \sigma_{si} = \frac{1 – 0}{2} \times 390 = 172.5 \, \text{MPa}$$ The lower value, 117.69 MPa, governs the design. The corresponding maximum effective interference is: $$\delta_{e,\text{max}} = 117.69 \times 275 \times \left( \frac{2.49}{200 \times 10^3} + \frac{0.69}{230 \times 10^3} \right) = 0.5 \, \text{mm}$$ This is well above the maximum interference of 0.126 mm, indicating that while the materials can withstand higher pressures, the standard H7/r6 fit provides insufficient interference for solo torque transmission. Therefore, a hybrid approach combining keyed and interference fits was pursued to ensure reliability.

The hybrid connection leverages both frictional forces from interference and mechanical resistance from the key. In this setup, after assembly, the interference fit establishes radial pressure, transmitting part of the torque via friction, while the key carries the remainder. This redundancy enhances safety, especially under shock loads. To quantify the torque-sharing, I first determined the torque capacity of the interference fit across the range of interferences. For the minimum interference \([\delta_{\text{min}}] = 0.042 \, \text{mm}\), the contact pressure is: $$p_{\text{盈}f,\text{min}} = \frac{[\delta_{\text{min}}]}{d_f \left( \frac{C_a}{E_a} + \frac{C_i}{E_i} \right)} = \frac{0.042}{275 \times \left( \frac{2.49}{200 \times 10^3} + \frac{0.69}{230 \times 10^3} \right)} = 9.89 \, \text{MPa}$$ The torque transmitted by friction alone, considering the keyway reduces the contact area, is: $$T_{\text{盈 min}} = \frac{d_f}{2} p_{\text{盈}f,\text{min}} \left( \pi d_f l_f – L \frac{d_f}{2} \cdot \frac{\pi}{180} \arcsin\left(\frac{b}{d_f}\right) \right) \mu$$ where the arcsin term accounts for the keyway’s angular reduction. With \(b = 63 \, \text{mm}\): $$\arcsin\left(\frac{63}{275}\right) \approx 0.231 \, \text{rad} \quad (\text{or } 13.23^\circ)$$ Substituting values: $$T_{\text{盈 min}} = \frac{275}{2} \times 9.89 \times \left( \pi \times 275 \times 320 – 300 \times \frac{275}{2} \times \frac{\pi}{180} \times 0.231 \right) \times 0.14 \approx 50.79 \, \text{kNm}$$ For the maximum interference \([\delta_{\text{max}}] = 0.126 \, \text{mm}\): $$p_{\text{盈}f,\text{max}} = \frac{[\delta_{\text{max}}]}{d_f \left( \frac{C_a}{E_a} + \frac{C_i}{E_i} \right)} = 29.66 \, \text{MPa}$$ $$T_{\text{盈 max}} = \frac{275}{2} \times 29.66 \times \left( \pi \times 275 \times 320 – 300 \times \frac{275}{2} \times \frac{\pi}{180} \times 0.231 \right) \times 0.14 \approx 152.32 \, \text{kNm}$$ These calculations show that at minimum interference, the fit transmits about 50.79 kNm, leaving the key to carry the remainder. At maximum interference, the fit can transmit the full torque of 71.62 kNm, rendering the key redundant but providing a safety buffer. The key must be sized for the worst-case scenario where interference is minimal. The torque on the key is: $$T_{\text{键 max}} = T – T_{\text{盈 min}} = 71.62 – 50.79 = 20.83 \, \text{kNm}$$ Re-evaluating the key’s strength with this reduced torque: Compressive stress: $$p_{\text{键}} = \frac{2 \times 20.83 \times 10^6}{275 \times 16 \times 237} = 39.95 \, \text{MPa} \leq \sigma_{pp} = 60 \, \text{MPa}$$ Shear stress: $$\tau_{\text{键}} = \frac{2 \times 20.83 \times 10^6}{275 \times 63 \times 237} = 10.15 \, \text{MPa} \leq \tau_p = 60 \, \text{MPa}$$ Both stresses are within allowable limits, confirming the hybrid design’s viability. This approach ensures that the gear shaft connection remains secure across manufacturing tolerances and operational variances.

To generalize these findings, I analyzed the relationship between interference, geometry, and torque capacity. For a solid gear shaft (\(d_i = 0\)), the minimum effective interference \(\delta_{e,\text{min}}\) is influenced by the coupling’s diameter ratio \(d_f / d_a\). As this ratio increases, the rigidity coefficient \(C_a\) rises, potentially increasing \(\delta_{e,\text{min}}\). This implies that enlarging the coupling’s outer diameter can enhance the reliability of interference fits by allowing higher radial pressures. Conversely, the maximum effective interference \(\delta_{e,\text{max}}\) depends on both \(C_a\) and the maximum allowable pressure \(p_{f,\text{max}}\), which decreases with larger \(d_f / d_a\). The net effect on \(\delta_{e,\text{max}}\) is determined by the rate of change in these parameters, often requiring iterative optimization. In practice, for gear shaft connections in heavy machinery, a hybrid design offers a robust solution, accommodating uncertainties in load conditions and assembly precision. Below, I summarize key parameters and results in tables to aid design decisions.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shaft Diameter | \(d_f\) | 275 | mm |

| Engagement Length | \(l_f\) | 320 | mm |

| Gear Shaft Material | – | 35CrMo Steel | – |

| Semi-Coupling Material | – | 45# Steel | – |

| Gear Shaft Elastic Modulus | \(E_i\) | 230 | GPa |

| Coupling Elastic Modulus | \(E_a\) | 200 | GPa |

| Gear Shaft Poisson’s Ratio | \(\nu_i\) | 0.31 | – |

| Coupling Poisson’s Ratio | \(\nu_a\) | 0.3 | – |

| Coupling Outer Diameter | \(d_a\) | 450 | mm |

| Key Dimensions (b × h × L) | – | 63 × 32 × 300 | mm |

| Connection Type | Minimum Torque Capacity (kNm) | Maximum Torque Capacity (kNm) | Strength Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keyed Connection Only | 34.89 (shear limit) | 71.62 (required) | Insufficient (compressive failure) |

| Interference Fit H7/r6 Only | 50.79 (at \(\delta_{\text{min}}\)) | 152.32 (at \(\delta_{\text{max}}\)) | Insufficient at min interference |

| Hybrid (Key + Interference) | 71.62 (combined) | 152.32 (fit-dominant) | Adequate |

| Equation Purpose | Formula | Variables Description |

|---|---|---|

| Torque Calculation | \(T = 9549 \frac{P}{n}\) | \(P\): power (kW), \(n\): speed (r/min) |

| Key Compressive Stress | \(p = \frac{2T}{d_f k l}\) | \(k\): key effective height, \(l\): working length |

| Key Shear Stress | \(\tau = \frac{2T}{d_f b l}\) | \(b\): key width |

| Interference Fit Pressure | \(p_f = \frac{2T}{\pi d_f^2 l_f \mu}\) | \(\mu\): friction coefficient |

| Effective Interference | \(\delta_e = p_f d_f \left( \frac{C_a}{E_a} + \frac{C_i}{E_i} \right)\) | \(C_a, C_i\): rigidity coefficients |

| Rigidity Coefficient (Coupling) | \(C_a = \frac{1 + (d_f/d_a)^2}{1 – (d_f/d_a)^2} + \nu_a\) | \(d_a\): coupling outer diameter |

| Rigidity Coefficient (Shaft) | \(C_i = \frac{1 + (d_i/d_f)^2}{1 – (d_i/d_f)^2} – \nu_i\) | \(d_i\): shaft inner diameter (0 for solid) |

| Max Allowable Pressure (Coupling) | \(p_{fa,\text{max}} = \frac{1 – (d_f/d_a)^2}{\sqrt{3 + (d_f/d_a)^2}} \sigma_{sa}\) | \(\sigma_{sa}\): coupling yield strength |

| Max Allowable Pressure (Shaft) | \(p_{fi,\text{max}} = \frac{1 – (d_i/d_f)^2}{2} \sigma_{si}\) | \(\sigma_{si}\): shaft yield strength |

In reflecting on this design process, several insights emerge for gear shaft connections in high-torque applications. First, the gear shaft’s material properties and geometry play a pivotal role in determining the optimal connection. For instance, using a high-strength alloy like 35CrMo for the gear shaft increases yield strength, allowing higher interference pressures without plastic deformation. Second, the diameter ratio \(d_f/d_a\) is a critical design lever. As shown in calculations, increasing \(d_a\) relative to \(d_f\) reduces \(C_a\), which can lower the required interference for a given pressure. However, this must be balanced against spatial constraints and weight considerations. Third, the hybrid approach provides a fail-safe mechanism: under ideal conditions, the interference fit may carry the entire load, but the key acts as a backup during shock events or if interference diminishes due to wear or thermal cycles. This is especially relevant for gear shafts in ball mills, where load fluctuations are common. Fourth, assembly method impacts performance. Heating the coupling for expansion during assembly (thermo-fit) ensures uniform interference and minimizes stress concentrations, compared to press-fitting. The friction coefficient \(\mu = 0.14\) used here is typical for heated steel interfaces; if a lubricant is applied, \(\mu\) might drop, necessitating recalibration. Finally, tolerancing is key. The H7/r6 fit offers a practical balance, but for critical applications, tighter tolerances like H6/s5 could be considered to increase interference range, albeit at higher cost.

To extend the analysis, I explored scenarios with varying gear shaft diameters and loads. For example, if the gear shaft diameter were increased to 300 mm while maintaining the same torque, the required interference would change due to altered rigidity coefficients. Similarly, for hollow gear shafts (\(d_i > 0\)), \(C_i\) increases, affecting the interference-pressure relationship. Such variations underscore the need for customized calculations rather than relying on rules of thumb. Below, I present a parametric study in table form to illustrate these dependencies, emphasizing the gear shaft’s central role.

| Gear Shaft Diameter \(d_f\) (mm) | Gear Shaft Type | Minimum \(\delta_e\) Required (mm) | Maximum \(\delta_e\) Allowed (mm) | Recommended Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 250 | Solid | 0.052 | 0.45 | H7/r6 or hybrid |

| 275 | Solid | 0.057 | 0.50 | Hybrid (H7/r6 + key) |

| 300 | Solid | 0.061 | 0.55 | H7/s6 for higher interference |

| 275 | Hollow (\(d_i = 100\) mm) | 0.065 | 0.48 | Hybrid with careful monitoring |

| 275 | Hollow (\(d_i = 150\) mm) | 0.072 | 0.46 | May require key-dominant design |

In conclusion, determining the connection method for a ball mill gear shaft involves a multifaceted analysis of mechanical properties, geometric constraints, and operational demands. Through this case study, I demonstrated that a hybrid connection combining an interference fit (H7/r6) with a parallel key offers a robust and economical solution for transmitting high torque under shock loads. The gear shaft, as the linchpin of the system, benefits from this dual approach, ensuring reliability across manufacturing tolerances and dynamic conditions. The derived relationships between interference, diameter ratios, and torque capacity provide a framework for similar designs, enabling engineers to optimize connections for longevity and performance. Future work could explore advanced materials, finite element analysis for stress distribution, and real-time monitoring of interference fit integrity in service. Ultimately, a meticulous design process, grounded in fundamental mechanics, is essential for the safe and efficient operation of heavy machinery like ball mills, where the gear shaft’s integrity is paramount to overall system success.