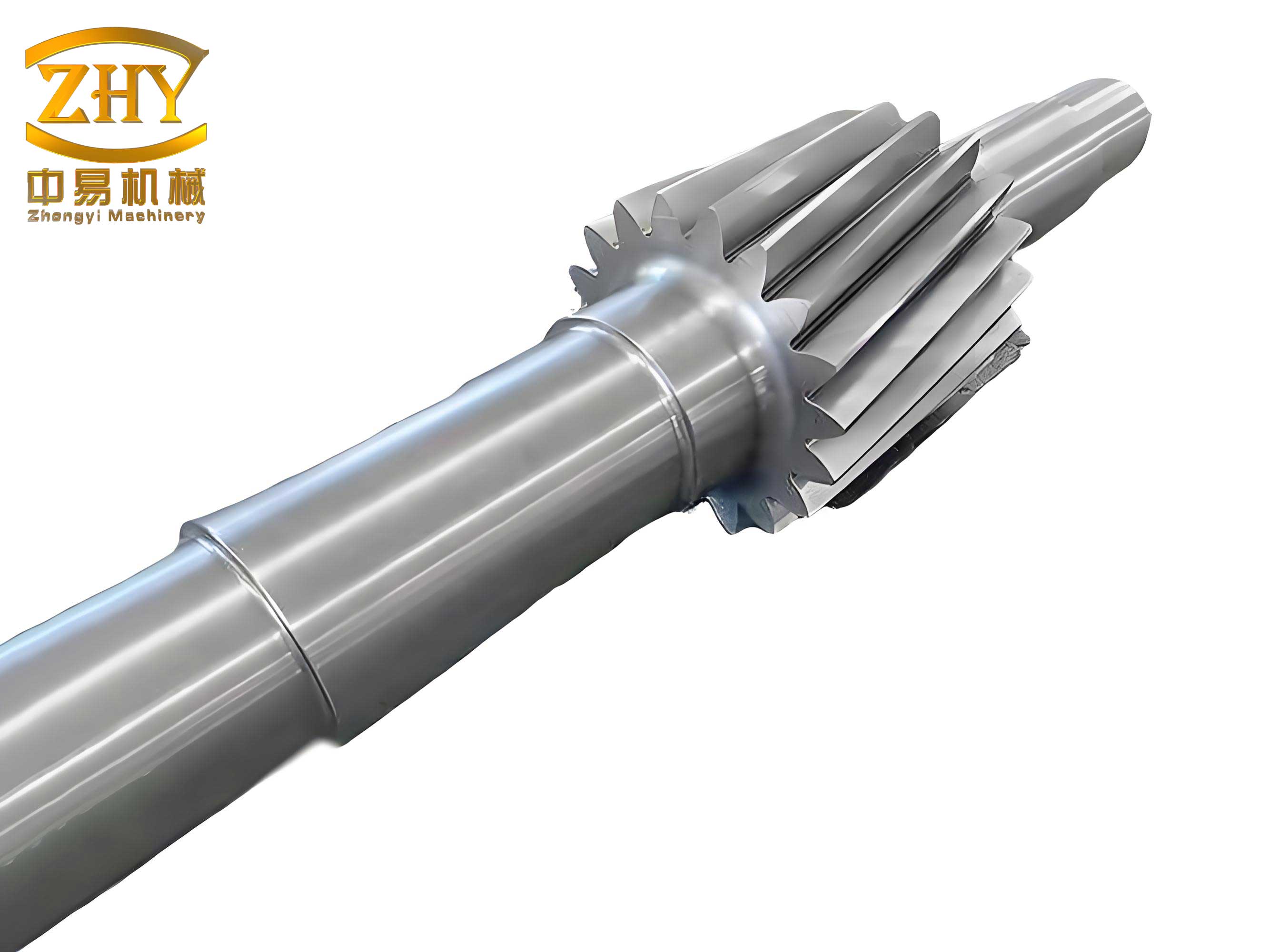

The gear shaft stands as a quintessential component within the power transmission systems of myriad mechanical equipment, most notably in reducers and gearboxes. These reducers, in turn, form the operational core of large-scale engineering machinery such as cranes, hoists, and construction equipment. Consequently, the structural integrity of the gear shaft, characterized by its static strength and stiffness, is not merely a determinant of the reducer’s service life but fundamentally influences the overall reliability and safety of the host machinery. This is of paramount importance in high-risk environments like mining and construction, where failure carries severe consequences. Therefore, a rigorous analysis of the static performance metrics of a gear shaft is an indispensable step in the design and validation process. The design of a gear shaft involves numerous structural parameters—both axial and radial dimensions—whose influence on its static characteristics is neither uniform nor intuitively obvious. Identifying and prioritizing the parameters to which these characteristics are most sensitive can dramatically enhance design efficiency and lead to more robust, optimized configurations. This treatise, therefore, delves into the comprehensive static and sensitivity analysis of a gear shaft, employing finite element methods and orthogonal experimental design to extract actionable design intelligence.

The foundation of any structural integrity assessment for a component like the gear shaft lies in static analysis. This involves determining the stress, strain, and deformation fields when the component is subjected to its maximum expected working loads. For a typical gear shaft in a multi-stage reducer, these loads are complex and multi-directional. They include radial and axial forces induced by both helical and bevel gears, as well as the transmitted torque. The primary static characteristics of interest are the maximum von Mises equivalent stress, which indicates the onset of yield according to the maximum distortion energy theory, and the maximum deformation, which is a direct measure of static stiffness.

The mathematical basis for static analysis in linear elasticity is governed by the equilibrium equations, constitutive relations (Hooke’s Law), and strain-displacement equations. For a three-dimensional continuum, the relationship between stress $\boldsymbol{\sigma}$ and strain $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}$ is given by:

$$\boldsymbol{\sigma} = \mathbf{D} \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}$$

where $\mathbf{D}$ is the material elasticity matrix. For an isotropic material like the 40Cr alloy steel commonly used for gear shafts, this matrix is defined by the Young’s modulus $E$ and Poisson’s ratio $\nu$. The static equilibrium condition, ignoring dynamic effects, is:

$$\nabla \cdot \boldsymbol{\sigma} + \mathbf{b} = 0$$

where $\mathbf{b}$ represents body forces. The finite element method (FEM) discretizes the complex geometry of the gear shaft into a mesh of simpler elements, transforming these continuous equations into a solvable system of linear algebraic equations:

$$\mathbf{K} \mathbf{u} = \mathbf{F}$$

Here, $\mathbf{K}$ is the global stiffness matrix assembled from individual element matrices, $\mathbf{u}$ is the nodal displacement vector, and $\mathbf{F}$ is the global force vector representing applied loads and constraints.

In our analysis, a gear shaft model is constructed and simplified by omitting non-critical features like keyways and small fillets to reduce computational cost without sacrificing result fidelity for the primary structural response. The material properties assigned are standard for 40Cr steel, as summarized in the table below.

| Material Property | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material | – | 40Cr Alloy Steel | – |

| Density | $\rho$ | 7850 | kg/m³ |

| Young’s Modulus | $E$ | 2.11 x 10⁵ | MPa |

| Poisson’s Ratio | $\nu$ | 0.277 | – |

| Yield Strength | $\sigma_y$ | 785 | MPa |

| Safety Factor (Selected) | $n$ | 1.7 | – |

| Allowable Stress | $[\sigma]$ | $\sigma_y / n \approx 461.8$ | MPa |

The loads are carefully applied to simulate real operating conditions. The forces from the helical and bevel gears are calculated from the input torque and gear geometry. For a helical gear, the tangential force $F_t$, radial force $F_r$, and axial force $F_a$ are derived from the transmitted torque $T$ and gear parameters like the pressure angle $\alpha_n$ and helix angle $\beta$:

$$F_t = \frac{2T}{d_m}, \quad F_r = F_t \frac{\tan \alpha_n}{\cos \beta}, \quad F_a = F_t \tan \beta$$

where $d_m$ is the mean pitch diameter. These forces are applied as distributed loads over the respective gear contact surfaces on the gear shaft to avoid artificial stress concentrations. Similarly, bearing reactions are applied as constraints. The resulting finite element model, typically meshed with solid (e.g., SOLID185/186) or tetrahedral elements, is then solved to obtain the stress and displacement fields.

The results of the static analysis for the example gear shaft reveal critical insights. The maximum von Mises stress is found to be approximately 94.8 MPa, located at the shoulder fillet transition between the bevel gear mounting section and the adjacent bearing seat. This stress concentration is typical in stepped shafts. Crucially, this maximum working stress is significantly lower than the material’s allowable stress of 461.8 MPa, confirming that the gear shaft possesses adequate static strength under the prescribed loads. The maximum deformation, occurring near another transitional section, is on the order of a few microns (e.g., 0.005 mm), indicating high static stiffness. This compliance check ensures that deflections do not adversely affect gear meshing accuracy or bearing operation.

While verifying that a design meets basic strength requirements is essential, the more sophisticated task is understanding *how* the design parameters influence performance. This is the realm of sensitivity analysis. For a gear shaft with many geometric parameters ($l_1, l_2, …, d_1, d_2, …$), sensitivity analysis quantitatively determines the rate of change of a performance function $f$ (e.g., maximum stress, mass, deflection) with respect to changes in a design variable $x_j$. The first-order local sensitivity $S_j$ at a given design point is defined as the partial derivative:

$$S_j = \frac{\partial f(\mathbf{X})}{\partial x_j}$$

where $\mathbf{X}$ is the vector of all design variables. A larger absolute value of $S_j$ indicates that the performance metric $f$ is more sensitive to variations in $x_j$. This information is invaluable for guiding optimization efforts, tightening manufacturing tolerances on critical dimensions, and performing robust design.

Several methods exist for sensitivity analysis, including direct analytic methods (requiring differentiable functions and access to solver gradients), finite difference methods, and sampling-based methods like the Design of Experiments (DoE). For complex, non-linear, or implicit functions—common in FEM results—sampling methods like Orthogonal Experimental Design (OED) are highly effective and algorithm-agnostic. OED employs specially constructed orthogonal arrays to sample the multi-dimensional design space efficiently with a minimal number of experiments (simulation runs).

In applying OED to the gear shaft, we select the maximum working stress $\sigma_{max}$ as the target response function $f$. We identify 11 key geometric parameters as factors. Each factor is assigned three levels (e.g., nominal, ± a small delta). An appropriate orthogonal array, such as an $L_{27}(3^{13})$ array which can accommodate 13 factors at 3 levels in only 27 runs, is chosen. The experimental layout defines 27 distinct geometric configurations of the gear shaft. For each run $i$, an FE model is built and solved to obtain the response $\sigma_{max}^{(i)}$.

The results are then analyzed using range analysis. For each factor $j$, we calculate the mean response $\bar{K}_{jm}$ at each level $m$ (e.g., $\bar{K}_{j1}$ is the average $\sigma_{max}$ for all experiments where factor $j$ was at level 1). The range $R_j$ for factor $j$ is the difference between the maximum and minimum of these level means:

$$R_j = \max(\bar{K}_{j1}, \bar{K}_{j2}, \bar{K}_{j3}) – \min(\bar{K}_{j1}, \bar{K}_{j2}, \bar{K}_{j3})$$

The factor with the largest $R_j$ has the greatest influence on the maximum stress of the gear shaft. Furthermore, the trend of the level means indicates the monotonicity of the effect—whether increasing the parameter increases or decreases the stress. For a two-level simplification, the sensitivity magnitude $|S_j|$ is proportional to the range and inversely proportional to the step size $\Delta x_j$ between levels:

$$|S_j| \approx \frac{R_j}{2 \Delta x_j}$$

The application of this methodology to our case study yields a clear hierarchy of parameter influence. The results, synthesized from the comprehensive experimental matrix, can be summarized as follows. The table below presents a conceptual summary of the sensitivity ranking for key parameters of the gear shaft.

| Rank | Structural Parameter | Description (Typical) | Relative Influence on $\sigma_{max}$ | Probable Effect (Trend) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $l_1$ | Axial length of first bearing span | Highest | Significant, non-linear |

| 2 | $d_5$ | Diameter of a central shaft section | Very High | Strong, inverse relationship |

| 3 | $d_4$ | Diameter of gear mounting section | High | Strong, inverse relationship |

| 4 | $l_5$ | Axial position of a load application point | Moderate-High | Moderate |

| 5 | $l_6$ | Axial overhang length | Moderate | Moderate |

| 6 | $d_2$ | Diameter of a transitional section | Moderate | Moderate |

| 7 | $l_3$ | Axial length of a gear section | Moderate-Low | Low |

| 8 | $l_2$ | Axial length within a bearing span | Low | Low |

| 9 | $l_4$ | Axial distance between features | Low | Low |

| 10 | $d_3$ | Diameter of another shaft section | Low | Very Low |

| 11 | $d_1$ | Diameter of a small bearing journal | Lowest | Negligible for global stress |

The profound insight here is that not all dimensions are created equal. The axial length $l_1$ (e.g., the distance between two bearing supports adjacent to the high-stress region) exhibits the dominant influence on the maximum stress in the gear shaft. This aligns with beam theory principles, where span length dramatically affects bending moment. Following closely are the diameters $d_5$ and $d_4$. According to the bending stress formula for a circular shaft, $\sigma_b \propto M / d^3$, where $M$ is the bending moment. The cubic relationship explains the high sensitivity; a small increase in these diameters drastically reduces bending stress. Conversely, parameters like $d_1$, which is typically on a remotely loaded and well-supported section, show minimal impact on the global peak stress. This sensitivity map provides a powerful directive: design optimization or tolerance analysis should focus primarily on $l_1$, $d_5$, and $d_4$ to efficiently control the stress state of the gear shaft.

The implications of this integrated static and sensitivity analysis extend far beyond a single design verification. For the design engineer, it transitions the process from iterative trial-and-error to a knowledge-driven activity. The methodology establishes a formal workflow: (1) Develop a validated FE model of the gear shaft under operational loads. (2) Conduct a baseline static analysis to ensure compliance with strength and stiffness criteria. (3) Define critical performance metrics and identify the full set of variable geometric parameters. (4) Employ an OED-based sensitivity study to rank these parameters by their influence. (5) Utilize this ranking to guide subsequent detailed optimization, where only the most sensitive parameters are varied, drastically reducing the search space and computational cost.

This approach is universally applicable to the design of power transmission components. For instance, in the development of a high-torque, compact gear shaft for aerospace or automotive applications, where weight is at a premium, the sensitivity analysis directly informs a mass minimization routine. The designer can aggressively adjust low-sensitivity dimensions to shed weight while carefully tuning high-sensitivity parameters like critical diameters and bearing spans to manage stress. Furthermore, in the context of robust design and manufacturing, knowing the sensitivity allows for the intelligent allocation of tolerances. Tight tolerances can be specified for high-sensitivity parameters like $d_4$ and $d_5$ to ensure consistent performance, while lower-sensitivity dimensions can have looser, more cost-effective tolerances.

In conclusion, the gear shaft is a component whose reliable function is critical to system safety and performance. A comprehensive analysis that marries detailed finite element-based static analysis with systematic, orthogonal-experiment-driven sensitivity analysis provides a deep and actionable understanding of its structural behavior. We conclusively demonstrate that the subject gear shaft meets all static strength requirements, with a maximum working stress well below the material’s allowable limit. More importantly, we distill the complex interplay of eleven design parameters into a clear hierarchy of influence, identifying the bearing span length and key section diameters as the primary drivers of stress performance. This hierarchical insight is the key to efficient optimization, robust design, and intelligent manufacturing of not only this specific gear shaft but also a broad class of analogous rotating power transmission components. The formalized methodology presented serves as a robust template for advancing from mere design verification to proactive, performance-driven design synthesis.