In my extensive experience with industrial machinery, I have observed that the drive gear shafts in large ball mills play a critical role in overall system reliability and operational costs. These gear shafts are often subjected to severe loading conditions, leading to frequent maintenance and replacement cycles. Traditionally, many ball mills utilize an integrated shaft-gear design, where the gear and shaft are forged as a single component. This approach, while common, presents significant drawbacks in manufacturing, maintenance, and economic efficiency. The primary issue lies in the fact that the gear, being a consumable part with a typical lifespan of 6 to 12 months, necessitates replacement far more often than the shaft, which is usually treated as a long-term component unless catastrophic failure occurs. However, with the integrated design, the entire assembly must be replaced, resulting in substantial material waste and increased downtime. This insight prompted me to undertake a comprehensive redesign project, focusing on separating the gear from the shaft to create a modular system. The core objective was to enhance the manufacturability, improve heat treatment uniformity, reduce spare parts consumption, and ultimately boost economic performance, all while ensuring the structural integrity and safety of the drive gear shafts. This article details my first-person perspective on the design process, strength verification, and practical outcomes of this improvement initiative for large ball mill drive gear shafts.

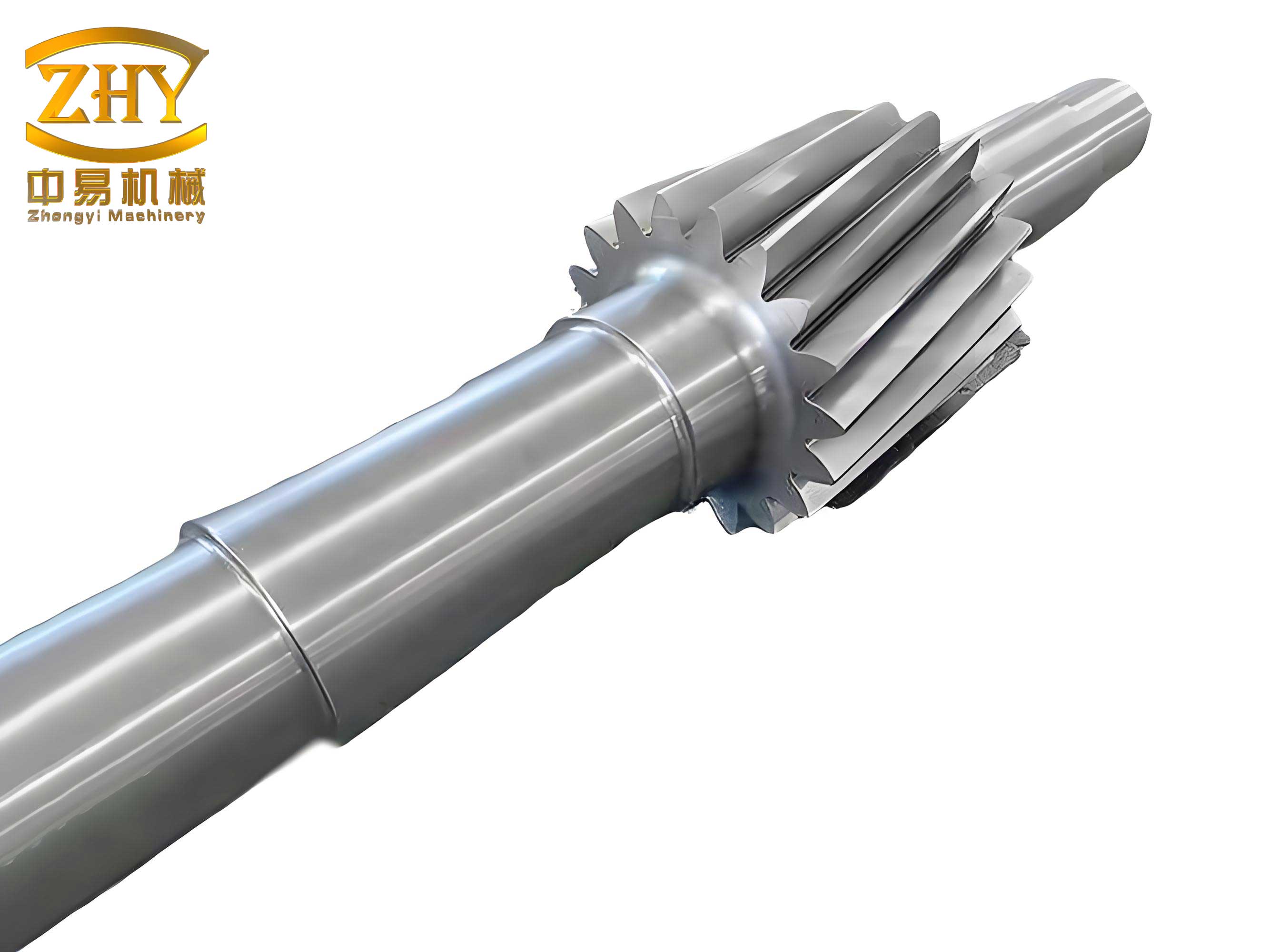

The ball mill in question is a crucial piece of equipment in mineral processing operations. Its drive system consists of a large synchronous motor connected via a gear coupling to an open-drive pinion shaft. This pinion, a key component among the drive gear shafts, meshes with a large ring gear fixed to the mill shell, thereby inducing rotational motion. The original manufacturer’s design featured an integrated shaft-gear assembly, as conceptually illustrated. This monolithic construction posed several challenges from a production standpoint. Forging such a large, complex blank was difficult and led to significant material wastage. Machining the gear teeth on such a component was cumbersome, and achieving consistent heat treatment across the different sections—the shaft requiring toughness and the gear teeth requiring surface hardness—was problematic. These manufacturing hurdles indirectly increased the procurement cost of these critical gear shafts and potentially compromised their service life.

My redesign philosophy centered on decoupling the gear from the shaft. The new configuration maintains all critical interface dimensions with existing components like couplings and bearings to ensure direct retrofit compatibility. The axial thrust from the gear, directed toward the motor, is managed by a dedicated shoulder on the shaft. I selected a fit diameter of Φ232 mm for the shaft-gear interface. To minimize stress concentration and reduce the forging size, the shoulder height was set at 9 mm with a generous transition fillet of R4. For assembly ease, the gear bore includes a 20 mm deep lead-in chamfer and is equipped with lifting screw holes. The resulting separated gear and shaft design is fundamentally more serviceable and economical. The following table summarizes the key design changes for these crucial gear shafts:

| Design Parameter | Original Integrated Design | Improved Modular Design |

|---|---|---|

| Component Structure | Single forged piece (Shaft & Gear) | Two separate pieces: Shaft and Gear |

| Gear Bore | N/A (Integral) | Φ232 mm fit diameter with lead-in chamfer |

| Shaft Shoulder | N/A | Height = 9 mm, Fillet R4 for axial location |

| Heat Treatment | Potentially non-uniform | Individual optimization for shaft (core toughness) and gear (surface hardness) |

| Replacement Strategy | Replace entire expensive assembly | Replace only the worn gear, reuse the shaft |

However, this modification significantly reduces the cross-sectional area of the shaft at the gear mounting location, which is the point of maximum bending moment. Therefore, a rigorous strength analysis of the new drive gear shafts was imperative to guarantee safety under full operational load. The fundamental load parameters for the mill are: transmitted power $P = 400 \text{ kW}$, shaft rotational speed $n = 187 \text{ r/min}$, gear normal module $m_n = 16 \text{ mm}$, pitch diameter $d_{div} = 433.8 \text{ mm}$, and helix angle $\beta = 5^\circ 15’$. The shaft material is 40Cr alloy steel, quenched and tempered to an ultimate tensile strength $\sigma_b = 700 \text{ MPa}$.

The force analysis on the gear, which is transmitted to the gear shafts, is the foundation of the stress calculation. The torque transmitted is:

$$ T = 9550 \times \frac{P}{n} = 9550 \times \frac{400}{187} \approx 20427.8 \text{ N·m} $$

The gear forces are then calculated as follows:

– Tangential Force: $$ F_t = \frac{2T}{d_{div}} = \frac{2 \times 20427.8}{0.4338} \approx 94180.7 \text{ N} $$

– Radial Force: $$ F_r = F_t \cdot \frac{\tan(\alpha_n)}{\cos(\beta)} = 94180.7 \times \frac{\tan(20^\circ)}{\cos(5.25^\circ)} \approx 34423.4 \text{ N} $$

– Axial Force: $$ F_x = F_t \cdot \tan(\beta) = 94180.7 \times \tan(5.25^\circ) \approx 8654 \text{ N} $$

Additionally, an allowance is made for an additional circumferential force $F_0$ due to coupling misalignment, typically taken as 30% of the nominal coupling force:

$$ F_0 = 0.3 \times \frac{2T}{d_{coupling}} = 0.3 \times \frac{2 \times 20427.8}{0.432} \approx 28371.9 \text{ N} $$

The shaft is modeled as a simply supported beam with concentrated loads. The reaction forces at the bearings (supports A and B) are calculated in two planes. The following table compiles the calculated reaction forces and bending moments, which are critical for assessing the stress on the gear shafts:

| Load Case & Plane | Calculation | Value (N or N·m) |

|---|---|---|

| Horizontal Reactions (Gear Loads) | $R_{AZ} = (F_r \cdot a – F_x \cdot d_{div}/2) / (a+b)$ | 15039.2 N |

| $R_{BZ} = F_r – R_{AZ}$ | 19384.2 N | |

| Vertical Reactions (Gear Loads) | $R_{AY} = R_{BY} = F_t / 2$ | 47090.4 N |

| Reactions (Misalignment Force $F_0$) | $R_{A0} = F_0 \cdot c / (a+b)$ | 35711.7 N |

| $R_{B0} = F_0 + R_{A0}$ | 64083.6 N | |

| Bending Moment at C (Horizontal) | $M_{CZ}’ = R_{BZ} \cdot b$ | 8374 N·m |

| Bending Moment at C (Vertical) | $M_{CY} = R_{AY} \cdot a$ | 20343 N·m |

| Resultant Bending Moment at C (Gear Loads) | $M_C’ = \sqrt{(M_{CZ}’)^2 + (M_{CY})^2}$ | 21999 N·m |

| Bending Moment from $F_0$ at B | $M_{B0} = F_0 \cdot c$ | 30784 N·m |

| Worst-Case Total Moment at C | $M_C = M_C’ + \frac{1}{2}M_{B0}$ | 37391 N·m |

| Transmitted Torque | $T$ (as above) | 20427.8 N·m |

The critical section for these drive gear shafts is at point C, where the gear is mounted, due to the combination of maximum bending moment, torque, and the stress concentration from the keyway. The stress state is analyzed considering fatigue strength. The bending stress is treated as fully reversed (symmetrical cycle) with an amplitude $\sigma_a$:

$$ \sigma_a = \frac{M_C}{W} $$

where $W$ is the section modulus for the shaft with a single keyway. For a shaft diameter $d = 232 \text{ mm}$ and key dimensions $b=56 \text{ mm}$, $t=2 \text{ mm}$:

$$ W = \frac{\pi}{32}d^3 – \frac{b t (d – t)^2}{2d} = \frac{\pi}{32} \times (0.232)^3 – \frac{0.056 \times 0.002 \times (0.232 – 0.002)^2}{2 \times 0.232} \approx 1.117 \times 10^{-3} \text{ m}^3 $$

Thus,

$$ \sigma_a = \frac{37391}{1.117 \times 10^{-3}} \approx 33.5 \text{ MPa} $$

The mean bending stress $\sigma_m = 0$ for symmetrical cycling.

The safety factor against bending fatigue $S_\sigma$ is calculated using the modified Goodman approach:

$$ S_\sigma = \frac{\sigma_{-1}}{\frac{K_\sigma}{\beta \varepsilon_\sigma} \sigma_a + \psi_\sigma \sigma_m} = \frac{\sigma_{-1}}{\frac{K_\sigma}{\beta \varepsilon_\sigma} \sigma_a} $$

For 40Cr material, the endurance limit $\sigma_{-1} = 320 \text{ MPa}$. The stress concentration factor for the keyway $K_\sigma = 1.89$, surface finish factor $\beta = 0.9$, size factor $\varepsilon_\sigma = 0.54$. Therefore,

$$ S_\sigma = \frac{320}{\frac{1.89}{0.9 \times 0.54} \times 33.5} \approx 2.45 $$

The torsional shear stress is considered as a pulsating (repeated) load. The shear stress amplitude and mean are equal:

$$ \tau_m = \tau_a = \frac{T}{2 W_\rho} $$

where $W_\rho$ is the torsional section modulus:

$$ W_\rho = \frac{\pi}{16}d^3 – \frac{b t (d – t)^2}{2d} \approx 2.343 \times 10^{-3} \text{ m}^3 $$

Thus,

$$ \tau_m = \tau_a = \frac{20427.8}{2 \times 2.343 \times 10^{-3}} \approx 4.4 \text{ MPa} $$

The safety factor against torsional fatigue $S_\tau$ is:

$$ S_\tau = \frac{\tau_{-1}}{\frac{K_\tau}{\beta \varepsilon_\tau} \tau_a + \psi_\tau \tau_m} $$

For 40Cr, $\tau_{-1} \approx 185 \text{ MPa}$, $K_\tau = 1.71$, $\varepsilon_\tau = 0.6$, $\psi_\tau = 0.21$.

$$ S_\tau = \frac{185}{\frac{1.71}{0.9 \times 0.6} \times 4.4 + 0.21 \times 4.4} \approx 12.4 $$

The combined safety factor $S$ for the gear shafts at the critical section is given by:

$$ S = \frac{S_\sigma \cdot S_\tau}{\sqrt{S_\sigma^2 + S_\tau^2}} = \frac{2.45 \times 12.4}{\sqrt{2.45^2 + 12.4^2}} \approx 2.4 $$

Since the allowable safety factor $[S]$ for such applications typically ranges from 1.3 to 2.5, and $S > [S]$, the redesigned drive gear shafts are confirmed to be safe under the specified operating conditions. This verification process underscores the robustness of the new modular design for these critical gear shafts.

Furthermore, the strength of the key connection, which transmits torque between the gear and the shaft in the new design, must be verified. The key selected is a parallel flat key (A-type) with dimensions $b \times h \times L = 56 \times 32 \times 400 \text{ mm}$. The working length is $l = L – b = 344 \text{ mm}$. The compressive bearing stress $\sigma_{jy}$ on the key is calculated assuming uniform pressure:

$$ \sigma_{jy} = \frac{2T}{d \cdot k \cdot l} $$

where the contact height $k = h/2 = 16 \text{ mm}$, and $d = 232 \text{ mm}$ is the shaft diameter.

$$ \sigma_{jy} = \frac{2 \times 20427.8}{0.232 \times 0.016 \times 0.344} \approx 32 \text{ MPa} $$

For material combinations of steel (shaft) and steel (gear hub), the allowable bearing stress $[\sigma]_{jy}$ is typically in the range of 100 to 120 MPa. Since $\sigma_{jy} < [\sigma]_{jy}$, the key connection for these gear shafts is more than adequate, ensuring reliable power transmission.

The economic impact of redesigning the drive gear shafts into a modular format has been profoundly positive. The separation of the gear from the shaft dramatically improves manufacturing logistics. The gear can now be produced using standard gear-cutting and heat-treating processes, leading to higher quality and consistency. The shaft, as a simpler forging, is easier and cheaper to manufacture. This broadens the supplier base and introduces competitive pricing. The following table quantifies the cost benefits observed, highlighting the advantage of maintaining separate inventory for these gear shafts:

| Cost Component | Original Integrated Shaft-Gear | Improved Modular System | Savings per Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procurement Cost (per assembly) | 28,000 currency units | Gear: 10,000 + Shaft: 13,000 = 23,000 | 5,000 currency units |

| Annual Replacement Cost* | 28,000 (full assembly) | 10,000 (gear only, shaft reused) | 18,000 currency units |

| Manufacturing Lead Time | Longer (complex forging/machining) | Shorter (simpler components, parallel processing) | Reduced downtime |

| Inventory Holding Cost | High (expensive single item) | Lower (can stock gears separately, fewer shafts) | Reduced capital tie-up |

*Assuming an annual gear replacement cycle and an infinite shaft life under normal conditions.

In practical application, the first set of improved modular gear shafts was installed and has been operating smoothly. The equipment runs with stability, and the gear wear pattern is even and predictable. Remarkably, the service life of the pinion gear has extended to approximately 18 months, exceeding the typical lifespan of the original integrated design, while the dedicated drive shaft remains in excellent condition, validating the durability engineered into these new gear shafts. This outcome not only reduces direct spare parts expenditure but also minimizes production interruptions, contributing significantly to overall plant productivity. The success of this project demonstrates that a thoughtful, analytically-backed redesign of fundamental components like drive gear shafts can yield substantial technical and economic rewards, enhancing the sustainability and profitability of industrial milling operations.

To further generalize the design principles, the stress analysis methodology applied here can be encapsulated in a set of universal formulas for verifying similar gear shafts. The bending stress amplitude is always critical:

$$ \sigma_a = \frac{M_{max}}{W} \quad \text{with} \quad W = \frac{\pi}{32}d^3 – \frac{b t (d – t)^2}{2d} \text{ for a keyed shaft}. $$

The fatigue safety factors are governed by material properties and stress concentrators:

$$ S_\sigma = \frac{\sigma_{-1}}{\left(\frac{K_\sigma}{\beta \varepsilon_\sigma}\right) \sigma_a}, \quad S_\tau = \frac{\tau_{-1}}{\left(\frac{K_\tau}{\beta \varepsilon_\tau}\right) \tau_a + \psi_\tau \tau_m}, \quad S = \frac{S_\sigma S_\tau}{\sqrt{S_\sigma^2 + S_\tau^2}}. $$

These equations form the cornerstone of reliable gear shafts design. Additionally, the key stress check remains:

$$ \sigma_{jy} = \frac{2T}{d \cdot k \cdot l} \leq [\sigma]_{jy}. $$

By adhering to these verification steps and embracing modularity, the lifecycle management of drive gear shafts becomes more efficient, cost-effective, and reliable, setting a benchmark for improvements in heavy machinery power transmission systems.