In my extensive experience with rotating machinery, the integrity of gear shafts is paramount to operational reliability. I recently investigated a critical failure involving gear shafts in a large air compressor at a power plant. These gear shafts are essential components, transmitting torque and supporting rotational dynamics within the system. The plant had initiated a localization program to replace expensive imported gear shafts with domestically manufactured versions to reduce costs. However, the first batch of these domestic gear shafts suffered premature fracture during service, falling far short of the design life expectancy. This prompted a detailed forensic analysis to uncover the root causes. My investigation employed a multi-faceted approach, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), metallographic examination, and hardness testing, complemented by a comparative study of an intact imported gear shaft. The findings reveal significant insights into the failure mechanisms and underscore the critical design and material considerations for such gear shafts.

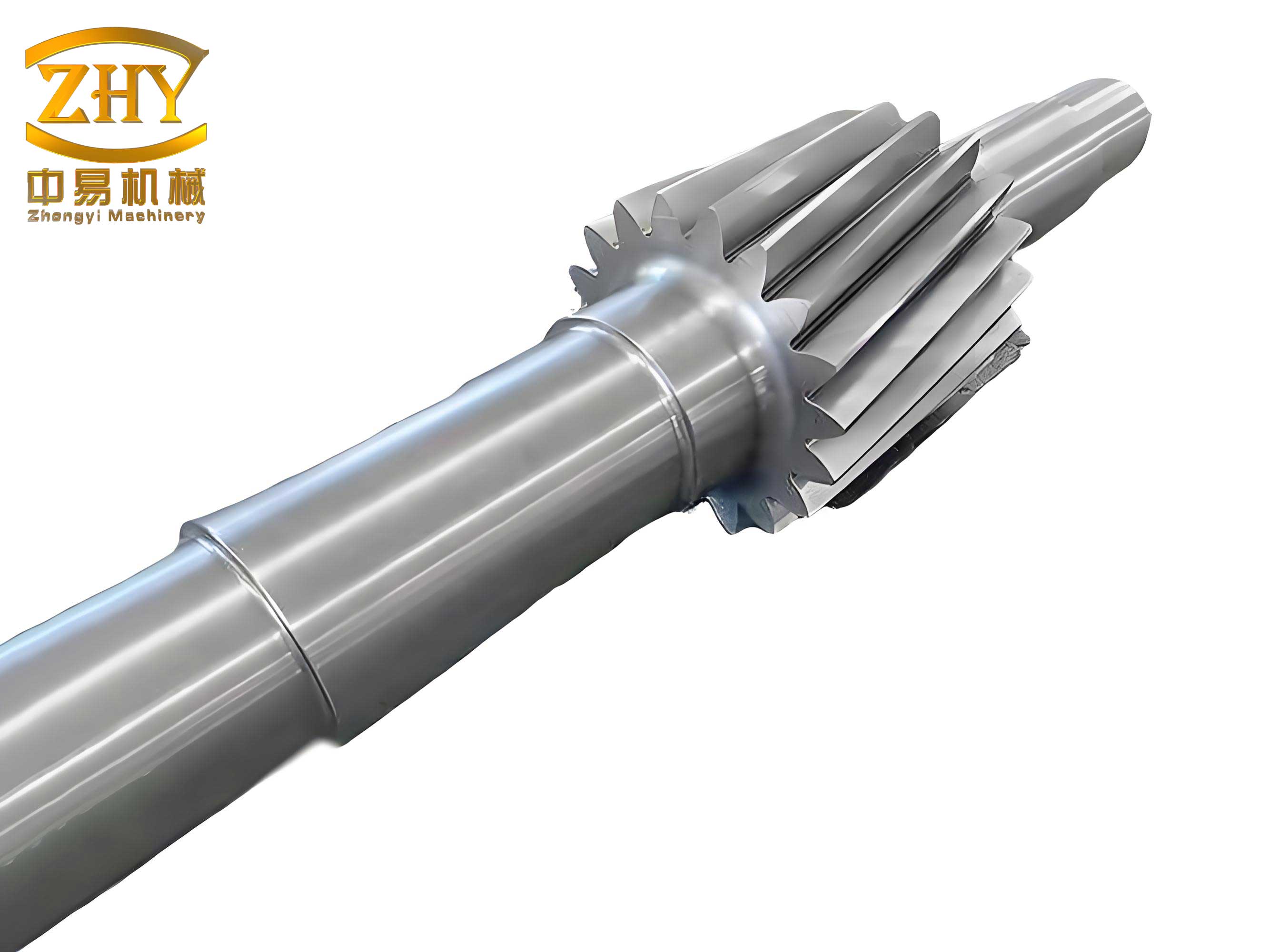

The primary objective was to determine why these gear shafts failed. Gear shafts, by their function, are subjected to complex cyclic loads. The specific gear shaft in question connects to an impeller via a unique triangular-profile end with a deep axial slot and a central threaded hole. This design aims to provide a frictional grip and drive transmission without additional pins. A bolt is tightened into the threaded hole, causing the slotted end to expand and clamp the impeller securely. My analysis began with a macroscopic and microscopic examination of the fracture surface.

The fracture occurred at the stress concentration site—the root of the axial slot where the shaft’s cross-section transitions. A low-magnification view of the fracture surface revealed definitive beach marks, characteristic of fatigue crack propagation. The crack initiation site was pinpointed to the sharp corner line at the slot root. Interestingly, the initial cracking appeared linearly along this entire corner line for approximately 1 mm before transitioning into a classic radial fatigue propagation pattern from the outer sharp corner of the slot root. SEM analysis of the fracture origin and propagation zones showed no evidence of detrimental冶金 defects like intergranular facets or excessive inclusions. The micro-mechanisms were typical of fatigue in a high-strength steel, with striations visible in the propagation region. This indicates that the failure of these gear shafts was initiated by fatigue.

To understand the contributing factors, I conducted a thorough comparative analysis of the material and manufacturing state between the failed domestic gear shafts and a reference imported gear shaft. The results are summarized in the following table, which highlights key disparities critical to the performance of gear shafts.

| Parameter | Domestic Gear Shaft | Imported Gear Shaft |

|---|---|---|

| Material Approx. | Similar to 12Cr2Ni4 steel | Similar to French 16CN6 steel |

| Key Alloying Element (Ni) | Higher Nickel Content | Lower Nickel Content |

| Core Microstructure | Tempered Martensite | Mixed Tempered Martensite & Bainite |

| Core Micro-hardness (HV0.1) | 437 HV | 354 HV |

| Estimated Tensile Strength (Rm) | ~1400 N/mm² | ~1150 N/mm² (estimated) |

| Slot Surface Treatment | Chrome Plating (~0.1 mm thick) | No Plating (Machined Surface) |

| Plating Micro-hardness (HV0.1) | ~1000 HV | N/A |

| Slot Machining Method | Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM) | Precision Grinding |

| Slot Root Geometry | Sharp Right-Angle Corner (No radius) | Sharp Right-Angle Corner (No radius) |

The material strength of the domestic gear shafts was significantly higher. Using the empirical relationship between hardness and tensile strength for ferrous materials, we can estimate:

$$ R_m \approx k \times HV $$

where \( k \) is an empirical constant (approximately 3.2-3.3 for quenched and tempered steels). For the domestic gear shaft core hardness of 437 HV:

$$ R_m^{domestic} \approx 3.25 \times 437 \approx 1420 \, N/mm^2 $$

This high strength, while often desirable for wear resistance in gear teeth, has implications for toughness and notch sensitivity. The notch sensitivity factor \( q \) can be approximated for high-strength steels subjected to fatigue:

$$ q = \frac{1}{1 + \frac{a}{\sqrt{r}}} $$

where \( r \) is the notch root radius (effectively zero for a sharp corner), and \( a \) is a material constant. For a sharp corner, \( q \) approaches 1, indicating full theoretical stress concentration. The actual stress concentration factor \( K_t \) for such a geometry is very high, often exceeding 3. The presence of a hard, brittle chrome plating layer on the domestic gear shafts introduced additional complications. The plating, with a hardness around 1000 HV, contained numerous micro-cracks. This layer creates residual tensile stresses at the surface and reduces the coefficient of friction. The lowered friction coefficient means that a higher bolt preload \( F_b \) is required to achieve the same clamping force \( F_c \) between the gear shaft and the impeller, according to the relationship:

$$ F_c = \mu \times F_b $$

where \( \mu \) is the coefficient of friction. A lower \( \mu \) necessitates a larger \( F_b \) to prevent slippage, thereby increasing the bending stress \( \sigma_b \) at the slot root during assembly. The bending stress can be modeled for the slotted cantilever-like section:

$$ \sigma_b = \frac{M \cdot y}{I} = \frac{(F_b \cdot L) \cdot (d/2)}{(\pi d^4 / 64)} $$

simplified for a circular cross-section near the root, but the actual triangular profile and slot complicate this. The key point is that increased preload directly raises the stress at the critical point.

The failure sequence for these gear shafts can be reconstructed as follows. During the installation of the impeller, the bolt tightening induced a high bending stress at the sharp corner of the slot root on the domestic gear shaft. The combination of a severe stress concentration (\(K_t\)), high material strength with lower ductility, and the embrittling effect of the chrome plating led to the initiation of micro-cracks along the entire corner line. This initial cracking likely occurred during assembly or the very early stages of operation. Once initiated, these micro-cracks served as potent fatigue crack starters. During compressor operation, the gear shaft is subjected to cyclic torsional and bending loads from the impeller. The stress intensity factor range \( \Delta K \) at the crack tip drives fatigue propagation:

$$ \Delta K = Y \Delta \sigma \sqrt{\pi a} $$

where \( Y \) is a geometry factor, \( \Delta \sigma \) is the cyclic stress range, and \( a \) is the crack length. The high stress concentration and residual stresses from plating ensured that \( \Delta K \) exceeded the threshold \( \Delta K_{th} \) for crack propagation even at relatively low operational loads. The crack then propagated in a stable fatigue manner, marked by beach lines, until the remaining cross-section could no longer support the load, leading to final overload fracture. The imported gear shaft, despite having the same sharp corner geometry, survived longer because its lower core hardness and absence of chrome plating resulted in a better stress-strain response, higher fracture toughness, and a more favorable friction condition requiring lower assembly preload. The toughness \( K_{IC} \) of a material generally decreases with increasing strength for similar steel grades. For high-strength steels used in gear shafts, the trade-off is critical:

$$ K_{IC} \propto \frac{1}{\sqrt{R_m}} $$

approximately for many alloy steels. The domestic gear shaft’s higher \( R_m \) implies a lower \( K_{IC} \), making it more susceptible to crack initiation from small defects or sharp notches.

The design philosophy for these gear shafts appears to have been misapplied during localization. Gear shafts often require differential property optimization along their length. The gear mesh section requires high surface hardness for wear resistance, typically achieved through case carburizing. However, the impeller connection end requires high friction, good ductility, and high fatigue strength—not necessarily high surface hardness. The domestic version incorrectly applied a uniform surface hardening concept via chrome plating to the entire end, which is detrimental. The following table contrasts the functional requirements and optimal treatments for different sections of such gear shafts.

| Gear Shaft Section | Primary Function | Key Mechanical Requirement | Optimal Surface Treatment | Desired Core Property |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gear Teeth Region | Transmit torque via meshing | High Surface Wear Resistance, High Contact Fatigue Strength | Case Carburizing or Nitriding | Tough, strong core to support hardened case |

| Impeller Connection End (Triangular Profile & Slot) | Clamp and drive impeller without slip | High Friction Coefficient, High Fatigue Strength, Good Notch Toughness | Phosphating or No treatment (Precision Machined) | Moderate Strength with High Ductility/Toughness |

| Bearing Journals | Rotate within bearings | High Wear Resistance, Good Dimensional Stability | Induction Hardening or Grinding to fine finish | Consistent hardness |

Therefore, the premature fracture of the domestic gear shafts was not due to a single flaw but a confluence of detrimental factors stemming from an incomplete understanding of the system’s mechanics. The primary cause was an inappropriate design and specification for the impeller end of the gear shafts, focusing on hardness over holistic performance. Specifically: 1) The application of a hard, crack-prone chrome plating at the high-stress slot root introduced tensile residual stresses, reduced friction (necessitating higher assembly stress), and provided easy crack initiation sites. 2) The excessively high core material strength (approx. 1400 N/mm²) reduced the material’s strain accommodation capacity and increased its notch sensitivity, making it less tolerant of the inevitable stress concentrator. 3) The sharp, right-angled corner at the slot root acted as a severe stress concentrator, with a theoretical stress concentration factor \( K_t \) that can be estimated for a shaft with a circumferential groove. For a groove with a flat-bottomed (sharp) root, \( K_t \) can be in the range of 4-5 or higher for bending. The fatigue strength reduction factor \( K_f \) is then:

$$ K_f = 1 + q (K_t – 1) $$

With \( q \approx 1 \) for this high-strength steel and sharp notch, \( K_f \approx K_t \). This drastically reduces the effective endurance limit \( \sigma_e’ \) of the material at that point:

$$ \sigma_e = \frac{\sigma_e’}{K_f} $$

where \( \sigma_e’ \) is the plain specimen endurance limit. For high-strength steels, \( \sigma_e’ \) is often approximately 0.5 of the tensile strength, but with a high \( K_f \), the component endurance limit can fall below the operational stress amplitude.

Based on this comprehensive analysis, I recommend the following corrective and preventive measures to enhance the fatigue performance and service life of these critical gear shafts. These measures are aimed at fundamentally improving the stress-strain state at the slot root and aligning the material properties with functional needs.

1. Eliminate Chrome Plating on the Impeller Connection Surface: The chrome plating on the slot and triangular profile must be completely removed from the specification. This will eliminate the associated residual tensile stresses, micro-cracks, and low friction coefficient. Instead, the surface should be finely machined or ground to a specified roughness to ensure an optimal friction grip with the impeller bore. Alternative surface treatments like phosphating could be considered if a controlled, slightly increased friction coefficient is needed without introducing significant embrittlement.

2. Optimize the Core Material Hardness and Toughness: The material grade and heat treatment for the gear shafts should be revised. The target for the impeller connection region should be a lower core hardness, akin to the imported shaft’s ~350 HV, which corresponds to a tensile strength around 1150 N/mm². This provides a better combination of strength and toughness. The gear teeth section can still be separately case-hardened to achieve high surface hardness. This differential heat treatment requires careful process control but is standard for high-performance gear shafts. The material selection could also be reviewed; a steel with better hardenability and toughness at moderate strength levels, such as a modified Ni-Cr-Mo grade, might be more suitable than the original high-Ni steel used in the domestic version.

3. Redesign the Slot Root Geometry to Mitigate Stress Concentration: The most critical mechanical improvement is introducing a radius at the sharp corner of the slot root. Even a small radius \( r \) can dramatically reduce \( K_t \). For a shaft with a circumferential groove under bending, the stress concentration factor can be approximated by Peterson’s formula:

$$ K_t = 1 + \frac{A}{\sqrt{r/d}} $$

where \( A \) is a constant depending on the groove geometry, and \( d \) is the shaft diameter. Introducing a radius changes the condition from a sharp corner (\( r \approx 0 \), \( K_t \to \infty \) theoretically) to a manageable stress riser. For example, if we design for a radius \( r = 1.0 \, mm \) at the slot root, \( K_t \) could be reduced to below 2. This would lead to a proportional increase in fatigue life \( N_f \), which is related to the stress range via the Basquin’s law:

$$ \sigma_a = \sigma_f’ (2N_f)^b $$

where \( \sigma_a \) is the stress amplitude, and \( \sigma_f’ \) and \( b \) are material constants. Reducing the local stress amplitude by a factor of \( 1/K_f \) through geometry improvement can increase fatigue life by orders of magnitude. The revised design should mandate a specified minimum root radius, and the slot should be manufactured using precision grinding instead of EDM to ensure better surface integrity and avoid the recast layer and micro-cracks associated with EDM, especially in high-strength steels for gear shafts.

In conclusion, the failure of the domestic gear shafts was a textbook case of fatigue fracture initiated at a stress concentrator, exacerbated by inappropriate material properties and surface treatment. The analysis underscores that successful design and manufacturing of critical components like gear shafts require a systems approach that considers assembly stresses, operational loads, and the nuanced property requirements of different component sections. The corrective measures of removing harmful plating, optimizing core hardness, and introducing a radius at the critical notch are straightforward yet powerful. Implementing these changes will fundamentally improve the stress state at the failure-prone location, thereby restoring and potentially exceeding the expected service life of these gear shafts. This case study serves as a crucial reminder for all engineers involved in the design and localization of high-stakes mechanical components like gear shafts: prioritizing holistic fitness-for-purpose over isolated material properties is key to reliability.