In the evolving landscape of offshore oil and gas exploration, the demand for robust and reliable jack-up platforms has intensified, particularly as operations extend into deeper and more hostile marine environments. The primary challenge lies in ensuring the structural integrity and stability of these platforms, where the increasing length of the legs exacerbates issues related to buoyancy and load transfer. A critical component in addressing this challenge is the locking mechanism that secures the platform’s legs to the hull, transferring the immense operational loads safely. This article presents a comprehensive design study, from my perspective as an engineering researcher, focusing on an innovative special worm gear and screw locking mechanism. The core of this system revolves around a screw gear transmission, which offers superior self-locking capability and compact design. Throughout this discussion, the term screw gear will be emphasized to underscore the integral role of this component in the proposed mechanism.

The conventional locking systems employed in many platforms, such as hydraulic pin systems or pneumatic locks, present limitations in deep-water applications, including discontinuous locking heights, high hydraulic pressure requirements, and complex leg machining. The gear-rack climbing system with toothed wedge locks represents an advancement, yet there is significant room for optimization in terms of weight, cost, and operational efficiency. My research is driven by the necessity for localization and technological independence in this sector, aiming to develop a locking system that is not only performant but also economically viable and manufacturable domestically. The proposed mechanism utilizes a vertically arranged dual-screw system actuated by a special worm gear drive, engaging toothed locking bars via wedge blocks. This design promises simplicity, reliability, and enhanced load distribution.

To understand the context, it is essential to review the prevalent locking schemes. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of three historical locking mechanisms, highlighting their drawbacks which motivate the new design.

| Locking Mechanism Type | Primary Operating Principle | Key Advantages | Major Disadvantages for Deep Water |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydraulic Pin Locking for Truss Legs | Hydraulic cylinders insert pins through aligned holes in the leg and hull. | Structurally simple, early adoption. | Shear stress on pins limits capacity; discontinuous locking height; long operational cycle; high-precision leg machining required. |

| Pneumatic Locking System | Compressed air actuates clamps or brakes to grip the leg. | Rapid actuation potential. | Less reliable under extreme, constant loads; sensitive to marine environment; requires complex air supply systems. |

| Gear-Rack System with Toothed Wedge Lock | Motor-driven pinions climb leg racks; separate toothed wedges are hydraulically driven to lock. | Continuous locking height; high load capacity. | Can be bulky; wedge alignment critical; system complexity can be high. |

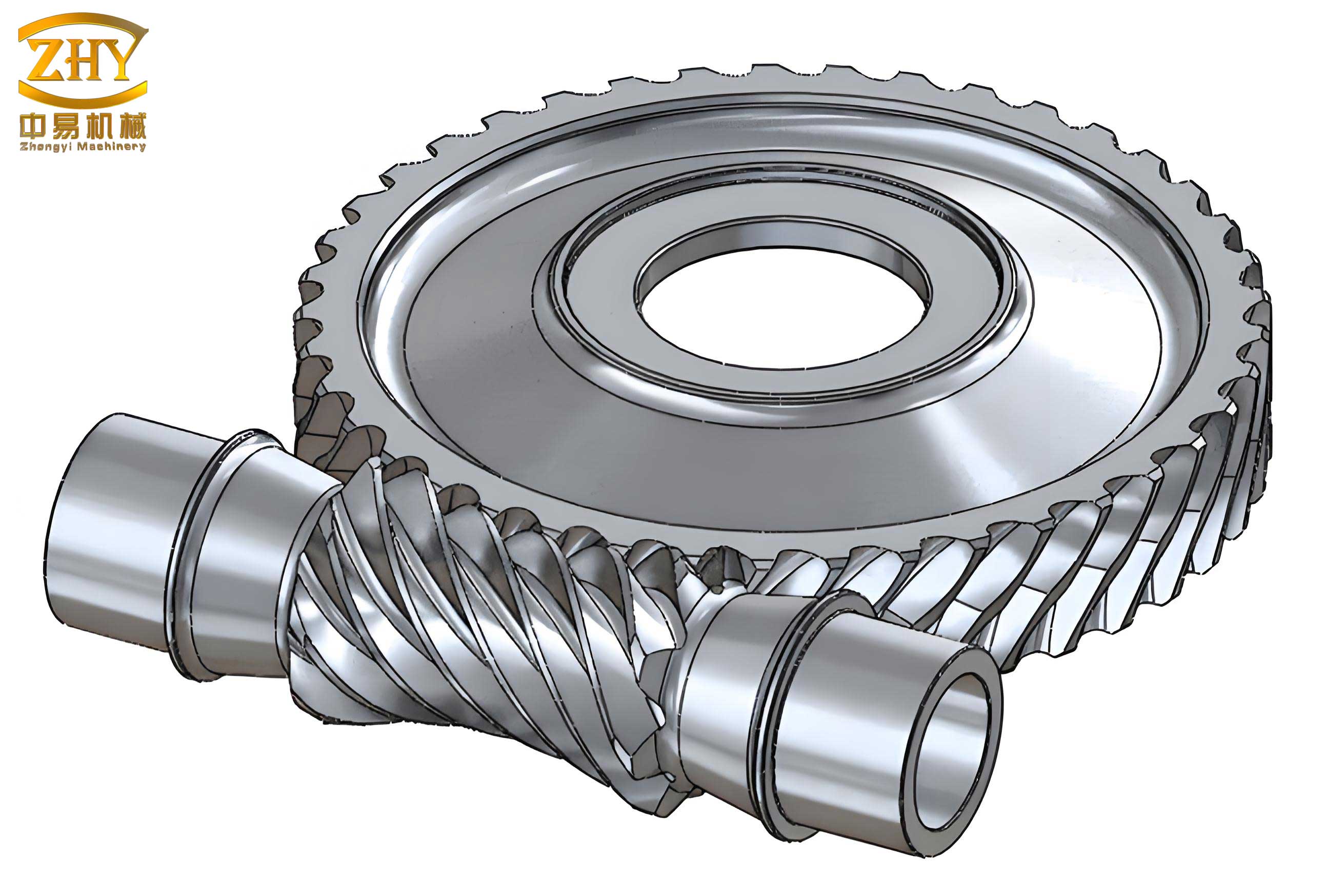

The proposed special worm gear and screw mechanism is conceived to mitigate these disadvantages. The core innovation lies in integrating a worm gear drive with a threaded screw, creating a highly efficient screw gear actuator. The fundamental operation involves six locking teeth per leg, each independently controlled by an upper and a lower screw assembly. These screws are driven by hydraulic motors via worm gear reducers. The worm gear’s internal bore is threaded, meshing directly with the screw’s threads, forming the essential screw gear pair. This configuration transforms the rotational motion of the worm wheel into precise linear motion of the screw, which then pushes a wedge block to clamp the locking tooth against the leg’s rack. The self-locking property of the worm drive, when the lead angle is less than the equivalent friction angle, is crucial for maintaining the lock without continuous power input.

The locking sequence for a single chord (one of the multiple leg columns) is methodical. First, the platform is lowered to the operational air gap. The lower screw assembly adjusts the height of the locking tooth. A side-thrust hydraulic cylinder then pushes the locking tooth into engagement with the leg rack. Subsequently, the upper hydraulic motor activates, rotating the worm gear and causing the upper screw to advance downward, forcing the upper wedge block to press on the locking tooth. Similarly, the lower motor drives the lower screw upward, engaging the lower wedge block. This dual-wedge action constrains the tooth both vertically and horizontally. After this pre-loading sequence is completed for all six teeth on a leg, the hydraulic systems are depressurized, transferring the entire leg load onto the six upper screw assemblies. Finally, the lower screws are adjusted upward to share the load, completing the secure locking process. The unlocking procedure is essentially the reverse, facilitated by the reversible hydraulic drive.

The mechanical design of the special worm gear and screw assembly requires detailed analysis. Let’s denote the worm gear as the driving element and the screw as the driven element in this screw gear pair. The primary kinematic relationship defines the linear travel of the screw per revolution of the worm gear. If the worm gear has \( N_w \) teeth and its internal thread has a lead \( L_s \) (distance advanced per revolution of the screw relative to the gear), the linear displacement \( \Delta x \) of the screw for a worm gear rotation angle \( \theta_w \) (in radians) is given by:

$$ \Delta x = \frac{L_s}{2\pi} \cdot \frac{\theta_w}{N_w} $$

However, since the worm gear is rotated by a worm with a single start or multi-start thread, the overall gear ratio \( i \) between the worm input shaft and the screw output is substantial. For a worm with \( z_1 \) starts and a worm gear with \( z_2 \) teeth, the speed ratio is \( i = z_2 / z_1 \). The screw’s lead \( L_s \) is a fixed property of its thread. Therefore, the final linear speed \( v_s \) of the screw relative to the input angular speed \( \omega_{in} \) of the worm shaft is:

$$ v_s = \frac{L_s}{2\pi} \cdot \omega_{in} \cdot \frac{1}{i} = \frac{L_s \cdot \omega_{in} \cdot z_1}{2\pi \cdot z_2} $$

The force analysis is critical for sizing components. The screw essentially acts as a power screw under high axial load \( F_a \), which is the reaction force from the wedge block clamping the locking tooth. The torque \( T_s \) required at the screw to overcome this load, neglecting friction in the wedge interface initially, is related to the screw’s efficiency. For a square thread (often assumed for power screws), the torque to raise the load is:

$$ T_s = \frac{F_a \cdot d_m}{2} \left( \frac{l + \pi \mu d_m \sec \alpha}{\pi d_m – \mu l \sec \alpha} \right) $$

Where:

\( d_m \) = mean diameter of the screw thread,

\( l \) = lead of the screw thread (\( L_s \)),

\( \mu \) = coefficient of friction between screw and worm gear internal thread,

\( \alpha \) = thread half-angle (0° for square thread, so \( \sec \alpha = 1 \)).

This torque \( T_s \) must be supplied by the worm gear. The torque on the worm gear \( T_g \) is related to the axial force on the screw. For a screw gear pair, the transmission efficiency \( \eta_{sg} \) from the worm gear rotation to screw translation can be derived. The input torque to the worm gear from the worm, \( T_{in} \), considering the worm gear drive efficiency \( \eta_{wg} \), is:

$$ T_{in} = \frac{T_g}{\eta_{wg}} = \frac{T_s}{ \eta_{sg} \cdot \eta_{wg} } $$

The self-locking condition for the entire mechanism is twofold: the worm drive must be self-locking, and the screw thread itself should also be self-locking to prevent back-driving. For the worm drive, self-locking occurs when the lead angle \( \gamma \) of the worm is less than the equivalent friction angle \( \phi \):

$$ \gamma < \phi = \arctan(\mu_{worm}) $$

Where \( \mu_{worm} \) is the coefficient of friction in the worm-worm gear mesh. For the screw thread, self-locking requires that the thread’s lead angle \( \lambda_s \) (where \( \tan \lambda_s = l / (\pi d_m) \)) is less than the friction angle \( \phi_s = \arctan(\mu) \). The proposed design carefully selects these angles to ensure that the screw gear assembly remains locked under load even if hydraulic pressure is lost.

The structural design of the components, such as the worm gear housing, screw, and wedge blocks, involves finite element analysis (FEA) to ensure stress levels are within permissible limits. The following table outlines key design parameters and material considerations for the primary components of the screw gear locking unit.

| Component | Primary Function | Key Design Parameters | Material & Treatment | Critical Stress Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worm Gear (with internal thread) | Convert hydraulic motor torque into rotary motion; engage with screw via internal threads. | Number of teeth \( z_2 \), module, pressure angle, internal thread pitch \( L_s \), lead angle. | Phosphor bronze (CuSn12) for good wear resistance and friction properties. | Bending stress at tooth root; contact stress at worm mesh; shear stress in threaded section. |

| Screw (Power Screw) | Translate rotary motion into linear force to actuate wedge blocks. | Major diameter, minor diameter, mean diameter \( d_m \), lead \( l \), thread type (square/trapezoidal). | Alloy steel (e.g., 4140) heat-treated to high tensile strength. | Combined axial compressive and torsional shear stress; thread bearing and shear stress. |

| Worm Shaft | Drive the worm gear; connected to hydraulic motor. | Number of starts \( z_1 \), lead angle \( \gamma \), module, shaft diameter. | Case-hardened steel (e.g., 20MnCr5) for high surface hardness. | Torsional shear stress; bending stress; contact stress with worm gear. |

| Upper/Lower Wedge Block | Transfer screw force to locking tooth; provide horizontal constraint via wedge angle. | Wedge angle \( \beta \), contact surface area, hardness. | Tool steel (e.g., D2) with surface hardening. | Hertzian contact stress against tooth; compressive stress. |

| Locking Tooth | Engage with leg rack; transmit platform load to wedges and screws. | Tooth profile (matching leg rack), width, root thickness. | High-strength, low-alloy steel (HSLA), quenched and tempered. | Bending stress as a cantilever; contact stress with rack and wedge. |

The load distribution among the six locking teeth is paramount for system reliability. Assuming the total vertical load \( P_{total} \) on one leg is equally shared by the six teeth in an ideal static condition, each tooth carries \( F_{tooth} = P_{total} / 6 \). However, due to manufacturing tolerances and elastic deformations, the load may not be perfectly uniform. The screw adjustment capability allows for fine-tuning to approach uniform loading. The force on each screw \( F_a \) is related to the wedge angle \( \beta \). From the wedge equilibrium, the horizontal reaction \( F_h \) (provided by the side-thrust cylinder initially and then by friction) and the vertical clamping force \( F_v \) (equal to \( F_{tooth} \)) are related by:

$$ F_v = 2 F_a \tan(\beta + \phi_w) $$ for the upper and lower wedges combined, assuming symmetrical wedging.

Where \( \phi_w \) is the friction angle at the wedge-tooth interface. Therefore, the required screw force \( F_a \) per tooth is:

$$ F_a = \frac{F_{tooth}}{2 \tan(\beta + \phi_w)} $$

A smaller wedge angle \( \beta \) reduces the required screw force but also reduces the mechanical advantage for unlocking and may compromise self-locking of the wedge interface. An optimal angle, typically between 5° and 15°, must be chosen. This force \( F_a \) is the axial load used in the screw torque calculation earlier.

The hydraulic system design must deliver sufficient torque and speed. The required hydraulic motor torque \( T_{motor} \) for each screw drive is:

$$ T_{motor} = \frac{T_{in}}{G_{reducer}} $$

where \( G_{reducer} \) is any additional gear reduction between the motor and the worm shaft. The worm gear drive itself provides the primary reduction. The hydraulic pressure \( p \) required, given a motor displacement \( D_m \) and efficiency \( \eta_m \), is:

$$ p = \frac{2\pi \cdot T_{motor}}{D_m \cdot \eta_m} $$

System reliability under dynamic ocean loads (waves, wind, currents) requires analysis beyond static loading. The locking mechanism must withstand fatigue cycles and shock loads. The dynamic amplification factor for the leg load can be significant. Using a simplified model, the dynamic load \( P_{dynamic} \) can be estimated from the static load \( P_{static} \) and a dynamic factor \( D_f \) derived from platform response analysis:

$$ P_{dynamic} = D_f \cdot P_{static} $$

where \( D_f \) may range from 1.2 to 2.0 depending on sea state. The screw gear assembly must be designed for this peak load. Fatigue analysis for the screw threads, a critical stress concentrator, involves calculating the alternating stress amplitude. For a fully reversing load (which is not the case here, as the load is mostly compressive), the Goodman criterion can be adapted. The mean stress \( \sigma_m \) and alternating stress \( \sigma_a \) in the screw root can be estimated. Given the high mean load, the focus is on ensuring the maximum stress under \( P_{dynamic} \) is below the yield strength with a safety factor, and the stress range is below the endurance limit for the material.

The efficiency of the overall screw gear transmission chain is a product of individual efficiencies: worm gear mesh efficiency \( \eta_{worm} \), screw gear (internal thread) efficiency \( \eta_{screw} \), and bearing efficiencies. The overall efficiency \( \eta_{total} \) from hydraulic motor input to mechanical work output on the wedge is low, typical for worm drives, but this is acceptable given the intermittent operation and the paramount need for self-locking. The efficiency of the worm gear itself depends on the lead angle and friction. An approximate formula for efficiency \( \eta_{worm} \) when driving (input is worm) is:

$$ \eta_{worm} = \frac{\tan \gamma}{\tan(\gamma + \phi)} $$

For the screw gear part (screw thread), the efficiency \( \eta_{screw} \) for raising the load is:

$$ \eta_{screw} = \frac{\tan \lambda_s}{\tan(\lambda_s + \phi_s)} $$

Thus, the total drive efficiency for the locking action is roughly \( \eta_{total} \approx \eta_{worm} \cdot \eta_{screw} \cdot \eta_{bearings} \). This low efficiency actually contributes to the self-locking characteristic, as it implies high friction that reserves back-driving.

Manufacturing and assembly considerations for the special worm gear are crucial. The internal threading of the worm gear to mate precisely with the screw is a non-standard machining operation. It requires specialized equipment to ensure the thread axis is concentric with the worm gear’s pitch circle and that the lead accuracy is maintained. The heat treatment processes for the different components must be carefully sequenced to avoid distortions that could affect the screw gear engagement. Furthermore, the assembly of the worm gear, bearings, and seals into the housing must allow for proper preloading of the tapered roller bearings to handle the combined axial and radial loads from the screw.

Comparative performance metrics between the proposed special worm gear system and a conventional pure hydraulic wedge lock (without a screw gear) can be tabulated. The following table illustrates these comparisons based on analytical models and assumed operational parameters for a typical deep-water jack-up platform.

| Performance Metric | Proposed Special Worm Gear & Screw Mechanism | Conventional Hydraulic Direct Wedge Lock | Remarks / Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Locking Capability | Inherent from both worm drive and screw thread; positive mechanical lock. | Relies on hydraulic pressure holding or non-return valves; susceptible to leakage. | The screw gear design provides fail-safe mechanical locking. |

| Load Distribution Control | Precise via individual screw adjustment; allows fine-tuning for equal load sharing. | Limited by hydraulic circuit balancing; less precise. | Enhanced structural integrity and longevity. |

| System Weight (for equivalent capacity) | Potentially lower due to efficient force amplification of screw; compact gear reducers. | Heavier due to larger hydraulic cylinders and associated structures. | Important for platform payload and stability. |

| Unlocking Speed & Control | Controlled, reversible via hydraulic motors; speed governed by motor RPM and gear ratio. | Fast but can be jerky; controlled by valve response. | Smooth operation protects components. | Maintenance & Servicing | Modular screw gear units; mechanical components standard (gears, bearings, screws). | Frequent seal replacements in hydraulic cylinders; potential for fluid leaks. | Reduced environmental risk and operational downtime. |

| Manufacturing Complexity | High for custom worm gear with internal thread (screw gear pair). | Lower for standard hydraulic components. | Justified by superior performance and localization benefits. |

| Energy Consumption per Lock Cycle | Higher instantaneous torque required but for shorter motor run time. | Continuous pressure may be needed to maintain lock if not mechanically locked. | Overall energy use may be comparable or lower due to intermittent operation. |

The mathematical modeling for system optimization involves several variables. We can formulate an optimization problem to minimize the total weight or maximize the safety factor. Let \( \mathbf{X} \) be a vector of design variables: worm gear module \( m \), number of teeth \( z_2 \), screw mean diameter \( d_m \), screw lead \( l \), wedge angle \( \beta \), etc. The objective function \( f(\mathbf{X}) \) could be the total mass of the locking unit for one leg. Constraints \( g_j(\mathbf{X}) \leq 0 \) include:

– Maximum stress in screw ≤ allowable stress / safety factor.

– Contact stress in worm mesh ≤ allowable pitting stress.

– Self-locking conditions: \( \gamma < \phi \) and \( \lambda_s < \phi_s \).

– Geometric constraints (e.g., housing size limits).

– Required locking time: Total screw travel \( \Delta x_{total} \) achieved within specified time \( t_{lock} \), relating to motor speed.

Solving this requires iterative methods or computational optimization tools. For instance, the screw diameter and lead influence both strength and efficiency. A larger diameter increases strength but also increases the required torque for a given load, as seen in the torque equation. The lead affects the travel speed and self-locking. The optimal screw gear configuration balances these factors.

Prototyping and testing are the next logical steps. A full-scale prototype of one screw gear actuator would undergo bench testing to verify torque-speed characteristics, efficiency, self-locking under load, and fatigue life. Strain gauges on the screw and housing would measure actual stresses. The data would validate the analytical and FEA models. Subsequently, integration into a test rig simulating a leg section would demonstrate the coordinated operation of all six units.

In conclusion, the design of a special worm gear and screw locking mechanism for jack-up platforms presents a compelling solution to the challenges posed by deep-water operations. The heart of this system, the integrated screw gear actuator, provides a robust, self-locking, and controllable means of load transfer. Through detailed mechanical analysis, incorporating formulas for kinematics, force, torque, and efficiency, the design parameters can be optimized. The use of tables to compare performance and list design specifications clarifies the advantages over conventional systems. This screw gear-based approach promises enhanced safety, reliability, and operational flexibility, contributing significantly to the goal of domesticating critical offshore technology. Future work will focus on refining the manufacturing process for the special worm gear, conducting extensive dynamic load testing, and exploring advanced materials to further reduce weight and increase the longevity of this vital screw gear locking mechanism.