In the design and application of electric valve actuators, the reliability and efficiency of the power transmission system are paramount. As the core mechanical transmission component, the performance of the screw gear set directly determines the actuator’s operational life, torque output, and control precision. Through extensive experimentation and analysis, I have focused on a critical yet often oversimplified parameter: the hardness matching between the worm (screw) and the worm wheel (gear). This article details my investigation, presenting a methodology for selecting optimal hardness pairings based on empirical data, and delves into the underlying wear mechanisms and efficiency implications. The goal is to move beyond conditional calculations and provide actionable guidelines to enhance the durability and performance of these ubiquitous power transmission elements.

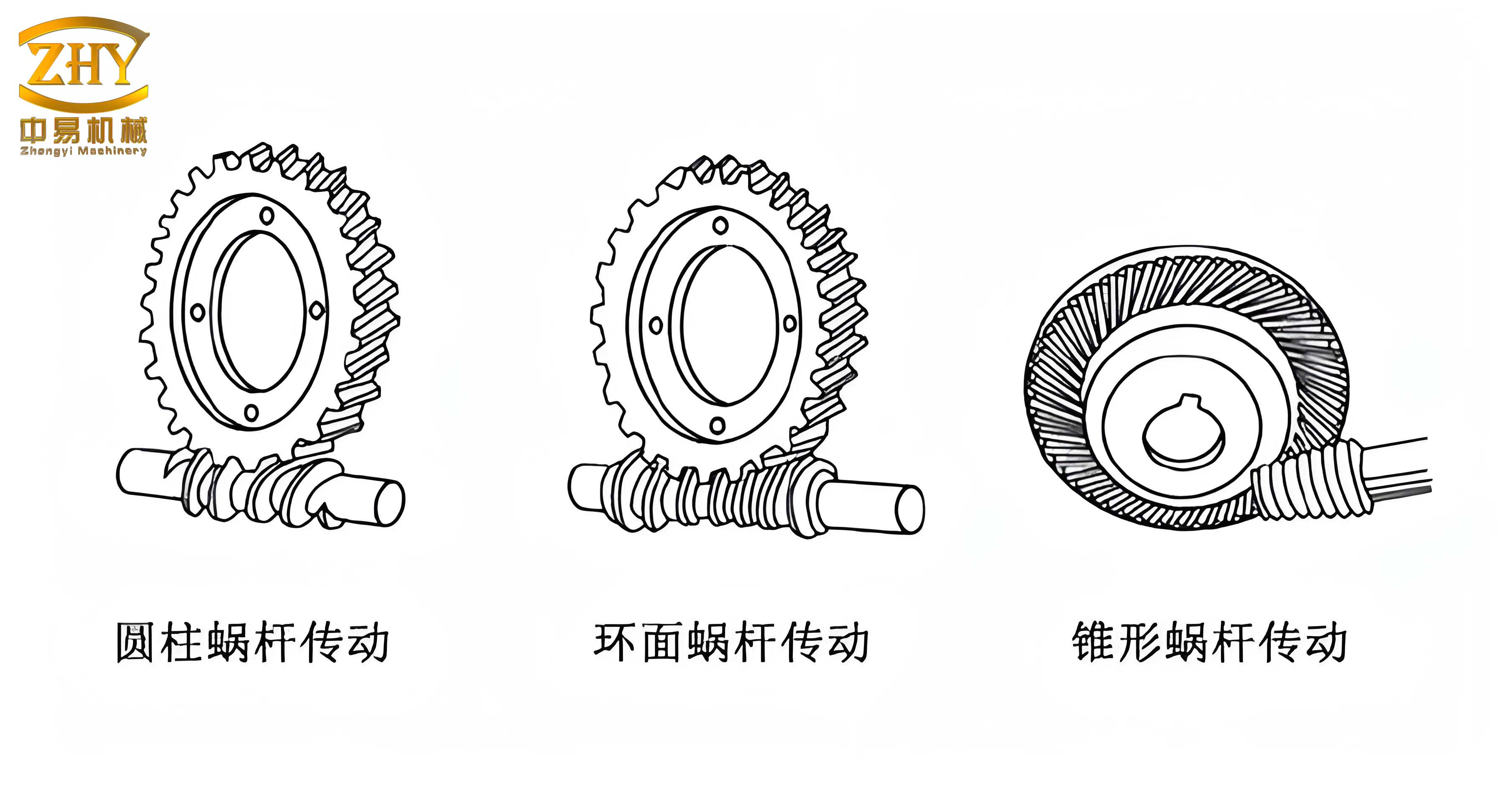

The fundamental role of a screw gear assembly within an electric actuator is to reduce the high speed of the electric motor to a lower, more usable output speed while significantly amplifying torque. The motion originates from the motor-driven worm, which engages with the teeth of the worm wheel. This wheel is directly connected to the stem of a valve or damper. A critical aspect of this design is its inherent self-locking tendency under certain conditions, which is beneficial for holding a valve position without continuous power input. The interaction between the worm and wheel is not purely rolling; it involves significant sliding contact along the tooth profiles. This sliding action, while enabling compact design and high reduction ratios, is the primary source of friction, heat generation, and ultimately, wear. Theoretically, the contact involves elastic and plastic deformation. When the material properties, particularly hardness, are mismatched, the softer component undergoes accelerated wear through mechanisms like abrasion, adhesion (scuffing or scoring), and fatigue pitting. Severe wear leads to a catastrophic decline in transmission efficiency and eventual failure of the screw gear set.

The selection of materials for screw gears in these applications varies widely. Common pairings include a hardened steel worm with a bronze alloy worm wheel, a steel worm with a cast iron wheel, or other non-ferrous wheel materials. The wear predominantly manifests on the teeth of the worm wheel, as it is typically the softer of the two. Failure modes include tooth bending fatigue fracture (common in cast iron wheels), adhesive wear (galling), abrasive wear, and surface fatigue pitting. A comprehensive theoretical model for predicting anti-scuffing and anti-wear performance remains elusive. Therefore, design often relies on conditional calculations for surface contact strength and tooth bending strength, supplemented heavily with experimental validation. Factors such as lubrication regime (boundary, mixed, or elastohydrodynamic), assembly alignment, and thermal management further complicate the prediction, making controlled testing of material and hardness combinations essential.

The experimental setup was designed to isolate and measure the influence of hardness matching on the performance of a screw gear pair. A standardized test rig was constructed, consisting of a fixed-specification motor directly coupled to the worm shaft. This worm engaged with the test worm wheel, which was connected to a programmable torque load and a precise speed sensor. The key to the methodology was measuring performance under a “stall-torque” condition. For each screw gear pair, the output was progressively locked. The motor was run until it stalled (reached its maximum stall torque), and the maximum output torque transmitted through the gear set at the point of stall was recorded. This method effectively captures the maximum transmissible torque, which is directly related to the system’s efficiency under peak load and provides accelerated wear conditions for observation. Since every component except the worm and wheel pair remained constant across all tests, any variation in measured output torque or observed wear could be attributed directly to the properties of the screw gear set under investigation.

The transmission efficiency of the screw gear pair, under the defined test conditions, can be derived from the power balance. The input power from the motor is related to its stall torque and speed, while the output power is zero at stall, but the transmitted torque is measurable. A more practical metric for comparison is the normalized output torque. However, for analytical purposes, the efficiency at the point just before stall can be conceptually expressed. The general efficiency formula for a worm gear set is:

$$

\eta = \frac{P_{out}}{P_{in}} = \frac{T_{out} \cdot \omega_{out}}{T_{in} \cdot \omega_{in}}

$$

Where \( \eta \) is the efficiency, \( T \) is torque, and \( \omega \) is angular velocity. In our controlled test, with constant motor input parameters (\(T_{motor-stall}\), \( \omega_{motor-no-load} \)), the measured output stall torque \( T_{out-stall} \) becomes the primary variable of interest. A higher \( T_{out-stall} \) for the same input indicates a more efficient screw gear pair with lower frictional losses. Therefore, we can define a comparative efficiency factor \( \eta_{comp} \) proportional to the output torque:

$$

\eta_{comp} = k \cdot T_{out-stall}

$$

Where \( k \) is a constant encapsulating the fixed motor parameters and gear ratio. The absolute value of efficiency is less critical here than the relative trend across different hardness combinations. The wear was qualitatively assessed post-test by examining the tooth surfaces of both the worm and the wheel for signs of adhesion (material transfer), abrasion (scoring), pitting, or plastic deformation.

Three distinct material pairings were tested, with the worm wheel hardness being the independent variable within each set.

Experimental Group 1: Case-Hardened Steel Worm vs. High-Strength Aluminum Bronze Wheel

The worm was manufactured from 15CrMn steel, with its thread surface case-hardened via carburizing to a depth of 0.5-0.8 mm, achieving a final surface hardness of approximately 60 HRC. The worm wheel was cast from ZCuAl9Fe4Ni4Mn2 (a high-strength nickel-aluminum bronze). Wheels with a range of bulk hardness values were procured and tested.

| Worm Wheel Hardness (HB) | Measured Output Stall Torque, \( T_{out} \) (N·m) | Comparative Efficiency Factor, \( \eta_{comp} \) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 110 | 660 | 17.6 |

| 123 | 880 | 23.4 |

| 131 | 1100 | 29.3 |

| 139 | 1350 | 35.9 |

| 150 | 1520 | 40.4 |

| 163 | 1680 | 44.7 |

| 175 | 1720 | 45.7 |

| 188 | 1790 | 47.6 |

Wear Observation: For wheels with hardness below 140 HB, severe abrasive wear (scratching) was observed on the wheel teeth. Significant transfer of bronze onto the hardened steel worm surface (plating or adhesion) was evident. This phenomenon diminished as wheel hardness increased.

Experimental Group 2: Through-Hardened Alloy Steel Worm vs. Standard Aluminum Bronze Wheel

The worm was made from 40Cr alloy steel, heat-treated to a through-hardness of 260 HB via quenching and tempering. The worm wheel material was ZCuAl10Fe3 (a standard aluminum bronze).

| Worm Wheel Hardness (HB) | Measured Output Stall Torque, \( T_{out} \) (N·m) | Comparative Efficiency Factor, \( \eta_{comp} \) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 108 | 890 | 23.7 |

| 112 | 1120 | 29.8 |

| 120 | 1220 | 32.4 |

| 125 | 1350 | 35.9 |

| 128 | 1400 | 37.2 |

| 131 | 1550 | 41.2 |

| 135 | 1690 | 44.9 |

| 142 | 1800 | 47.9 |

Wear Observation: Wear modes were predominantly mild abrasive wear and incipient surface fatigue pitting. Material transfer from the wheel to the worm was minimal. The wear scars were less severe overall compared to Group 1 at similar low hardness levels.

Experimental Group 3: Case-Hardened Steel Worm vs. Standard Aluminum Bronze Wheel

This group combined the hard worm from Group 1 (15CrMn, 60 HRC) with the wheel material from Group 2 (ZCuAl10Fe3).

| Worm Wheel Hardness (HB) | Measured Output Stall Torque, \( T_{out} \) (N·m) | Comparative Efficiency Factor, \( \eta_{comp} \) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 110 | 580 | 15.4 |

| 116 | 610 | 16.2 |

| 125 | 680 | 18.1 |

| 132 | 750 | 19.9 |

| 139 | 790 | 21.0 |

| 147 | 990 | 26.3 |

| 153 | 1080 | 28.7 |

| 158 | 1380 | 36.7 |

Wear Observation: This combination exhibited the most severe adhesive wear. For wheels with hardness below approximately 140 HB, extensive damage and gouging occurred on the wheel teeth. The bronze transfer to the hard worm surface was copious and pronounced, indicating a strong tendency for galling and seizure under load.

Analysis of Hardness Matching and Performance

The data from these systematic tests reveal profound insights into the behavior of screw gear sets under load. A primary performance threshold was established based on a common design requirement for the actuator: a minimum output stall torque of 1100 N·m. Analyzing which combinations met or exceeded this threshold provides the first key guideline.

1. The Critical Minimum Wheel Hardness: For screw gear sets utilizing a hardened steel worm, the worm wheel hardness must exceed a critical value to achieve acceptable performance and life. In all groups featuring a hardened worm (Groups 1 & 3), the output torque remained below the 1100 N·m threshold until the wheel hardness reached approximately 130-140 HB. Specifically, for the high-strength bronze in Group 1, the threshold torque was achieved at 131 HB. For the standard bronze paired with the same hard worm in Group 3, the torque did not reliably meet the threshold until the hardness approached 150 HB. This leads to a fundamental design rule: For electric actuator screw gears with a hardened steel worm, the bronze worm wheel should have a minimum bulk hardness of 130 HB, with a target of 140-150 HB or higher for optimal performance. Wheels softer than this limit suffer rapid, catastrophic wear, rendering the actuator unfit for industrial service.

2. The Role of Hardness Difference (ΔHB): The experiments clearly demonstrate that the absolute hardness difference between the worm and the wheel is a critical parameter. We can define this difference as:

$$

\Delta HB = |HB_{worm} – HB_{wheel}|

$$

In Group 2, where the through-hardened worm had a hardness of 260 HB, the ΔHB ranged from ~118 to ~152. This relatively smaller difference (compared to the ~400+ HB difference in groups with a case-hardened worm) correlated with generally higher efficiency factors at lower wheel hardness and less severe adhesive wear. The screw gear pair exhibited more “compatible” wear characteristics. Conversely, in Groups 1 and 3, the extremely high worm surface hardness created a massive ΔHB. While a high ΔHB can be beneficial for wear resistance if the wheel is sufficiently hard, it becomes detrimental if the wheel is too soft, as seen in Group 3. The data suggests an optimal window for ΔHB exists—large enough to ensure the worm resists wear, but not so large as to promote aggressive plowing and adhesion when paired with a moderately hard wheel. An excessively large ΔHB with a soft wheel leads to low efficiency and high wear rates, as the hard asperities on the worm easily penetrate and plough through the soft wheel material. The wear volume \( W \) can be conceptually related to hardness and load by an abrasive wear model:

$$

W \propto \frac{K \cdot L \cdot s}{H}

$$

Where \( K \) is a wear coefficient, \( L \) is the load, \( s \) is the sliding distance, and \( H \) is the hardness of the softer material (the wheel). This explains why increasing wheel hardness (H) directly reduces wear volume. However, the wear coefficient \( K \) itself changes with the material pairing and the severity of interaction, which is influenced by ΔHB.

3. The Influence of Wheel Material Grade: Comparing Group 1 and Group 3 is instructive. Both used the same hard worm but different bronze alloys. At similar hardness levels, the high-strength nickel-aluminum bronze (Group 1) consistently showed higher output torque and efficiency than the standard aluminum bronze (Group 3). For example, at a wheel hardness of ~139 HB, Group 1 produced 1350 N·m, while Group 3 produced only 790 N·m. This underscores that hardness alone is not a sufficient metric; the underlying material’s strength, microstructure, and anti-galling properties are crucial. The nickel-aluminum bronze inherently offers better resistance to adhesive wear and higher fatigue strength, contributing to superior screw gear performance even at equivalent hardness.

4. Wear Mechanism Transition: The post-test observations map a transition in wear mechanism based on hardness matching:

- Very Low Wheel Hardness (<130 HB) with Hard Worm: Dominated by severe adhesive wear (galling) and abrasive wear. High material transfer, low efficiency.

- Moderate Wheel Hardness (130-180 HB) with Hard Worm: Wear shifts towards milder abrasive wear and surface fatigue. Material transfer reduces significantly, efficiency rises and stabilizes.

- Moderate Wheel Hardness with Through-Hardened Worm (Smaller ΔHB): Primarily fatigue pitting and mild abrasion. Minimal adhesion, highest efficiency stability across the range.

This transition highlights the importance of selecting a hardness pair that promotes benign wear modes (like fatigue) over catastrophic ones (like adhesion).

Synthesis and Design Guidelines for Screw Gears

Integrating these experimental results leads to a coherent framework for specifying screw gear hardness in electric valve actuators. The following guidelines and formulas can aid in the selection process.

Guideline 1: Establish Minimum Wheel Hardness.

For bronze worm wheels paired with steel worms (case-hardened or through-hardened), specify a minimum bulk hardness of 130 HB. For critical or high-load applications, increase this minimum to 140-150 HB. This provides a safety margin against the rapid wear zone.

Guideline 2: Optimize the Hardness Difference.

Avoid extreme hardness differences when the wheel is of moderate hardness. While a very hard worm is desirable, ensure the wheel is proportionally hard enough to withstand interaction. A target ΔHB can be approximated. For preliminary design with bronze wheels:

– For case-hardened worms (>55 HRC / ~550 HB), aim for wheel hardness >140 HB (ΔHB < ~410).

– For through-hardened worms (e.g., 250-300 HB), a wheel hardness of 130-180 HB provides a good balance (ΔHB ~70-170).

Guideline 3: Prioritize High-Performance Bronze Alloys.

When efficiency and longevity are critical, select bronze alloys known for high strength and anti-galling properties (e.g., nickel-aluminum bronzes like ZCuAl9Fe4Ni4Mn2) over standard alloys, even at similar hardness levels.

Guideline 4: Consider a Comparative Performance Estimator.

Based on the trend data, the relative performance of a screw gear pair can be initially gauged by a simplified empirical relation. While not a substitute for testing, an estimator for the comparative efficiency factor (\( \eta_{comp} \)) can be framed as a function of worm wheel hardness (\( HB_w \)) and the material pairing factor (\( C_m \)):

$$

\eta_{comp} \approx C_m \cdot (HB_w – HB_{critical}) \quad \text{for} \quad HB_w > HB_{critical}

$$

Where:

\( HB_{critical} \) is approximately 100-110 HB (the point where efficiency trendlines from our data tend to intercept the low-torque region).

\( C_m \) is a material coefficient derived from testing (e.g., higher for high-strength bronze with a hard worm, lower for standard bronze with the same worm).

For the tested pairs, approximate linear fits in the effective operating range (HB_w > 130) yield:

– Group 1 (Hard Worm/High-Strength Bronze): \( \eta_{comp} \approx 0.50 \cdot (HB_w – 110) \)

– Group 2 (Through-Hard Worm/Std. Bronze): \( \eta_{comp} \approx 0.55 \cdot (HB_w – 100) \)

– Group 3 (Hard Worm/Std. Bronze): \( \eta_{comp} \approx 0.43 \cdot (HB_w – 110) \)

These simplistic linear models illustrate the steeper performance gain with hardness for more compatible pairs (Group 2) and the lower baseline performance of the problematic pair (Group 3).

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

The performance of a screw gear set in an electric actuator is not solely determined by geometric design and lubrication; it is intimately governed by the tribological partnership between the worm and wheel, for which hardness matching is a master variable. This investigation substantiates that a bronze worm wheel hardness below 130 HB is generally unacceptable for industrial duty, leading to poor efficiency and rapid failure. Furthermore, it reveals that an excessively large hardness differential, particularly when coupled with a softer, less capable bronze alloy, exacerbates adhesive wear mechanisms. The optimal path is to select a high-integrity bronze alloy and specify a hardness sufficiently high to work in concert with a hard worm, thereby promoting favorable surface fatigue wear over destructive galling and abrasion.

Controlling worm hardness is relatively straightforward through established heat treatment processes. The greater challenge lies in consistently achieving the specified hardness and metallurgical quality in the cast bronze worm wheel, as it is influenced by foundry practice, alloy composition, cooling rates, and possible post-casting treatments. Future work should focus on correlating bulk hardness with microstructural features (phase distribution, grain size) and developing non-destructive testing methods to ensure each screw gear component meets the required tribological standard. By mastering hardness matching, we move closer to reliably engineering screw gear sets that deliver maximum efficiency and longevity in the demanding environment of valve automation.