In mechanical engineering, screw gears, particularly the Archimedes type, are widely used for transmitting motion and power between non-intersecting shafts. As a designer, I have extensively utilized SolidWorks, a powerful 3D CAD software, to create accurate parametric models of these screw gear components. This article details my firsthand approach to modeling and assembling Archimedes screw gears, emphasizing the underlying mathematical equations and the step-by-step procedures within SolidWorks. The parametric design not only accelerates the development cycle but also lays a solid foundation for subsequent finite element analysis, mechanism simulation, and even CNC machining. Through this process, the significance of screw gear geometry in precision engineering becomes profoundly clear.

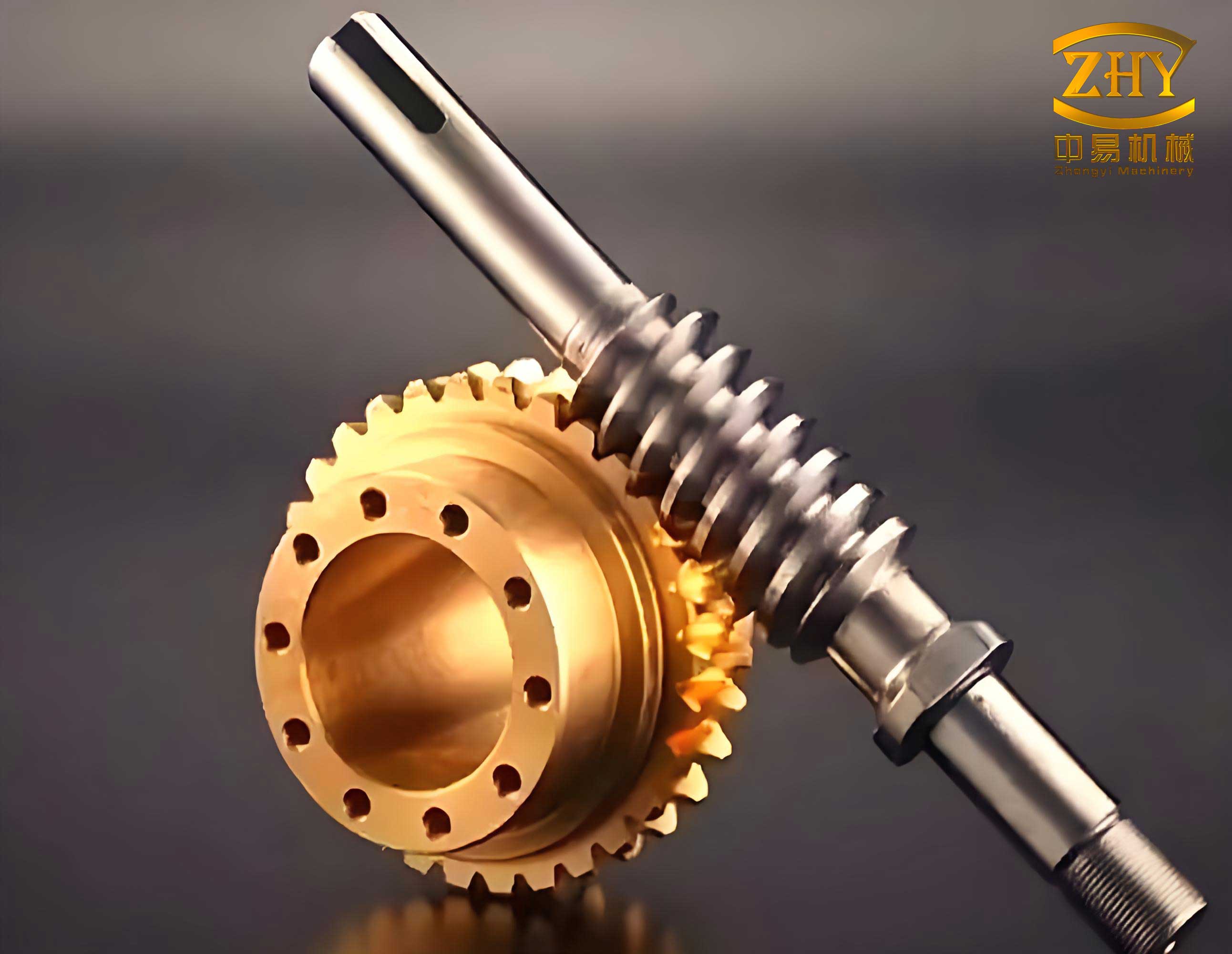

The fundamental geometry of an Archimedes screw gear pair involves a worm (the screw) and a worm wheel. In the middle plane, their engagement resembles that of a rack and pinion. The worm’s axial profile is trapezoidal, while the worm wheel’s tooth profile in this plane is an involute. Understanding these profiles mathematically is crucial for accurate 3D modeling.

For the Archimedes worm, the tooth flank is generated by a trapezoidal section performing a helical motion around the worm axis. The coordinates of key points on this axial profile are essential. Let’s define the parameters: module \(m\), pressure angle \(\alpha = 20^\circ\), addendum coefficient \(h_a^* = 1\), dedendum coefficient \(c^* = 0.2\), worm pitch diameter \(d_1 = m q\), where \(q\) is the diameter factor. The axial pitch is \(p_a = \pi m\). The addendum height is \(h_a = h_a^* m\), and the dedendum height is \(h_f = (h_a^* + c^*) m\). The worm’s reference circle radius is \(r_1 = m q / 2\). The coordinates of points on the trapezoidal profile in the axial plane can be expressed. For point 1 (on the dedendum circle) and point 3 (on the addendum circle), the equations are:

$$x_1 = p_a / 4 – h_f \tan \alpha, \quad y_1 = r_{f1} = r_1 – h_f$$

$$x_3 = p_a / 4 + h_a \tan \alpha, \quad y_3 = r_{a1} = r_1 + h_a$$

Points 2 and 4 are symmetric to points 1 and 3 about the y-axis. This trapezoid, when swept along a helix defined on the worm’s pitch cylinder, creates the precise worm thread. The helix is characterized by its lead angle \(\gamma\), where \(\tan \gamma = \frac{m z_1}{d_1}\), with \(z_1\) being the number of worm starts.

Modeling the worm wheel is more intricate. Its tooth profile in the middle plane is an involute curve. The parametric equations for an involute, starting from the base circle, are fundamental for any screw gear design. Let \(r_2\) be the worm wheel’s pitch radius, \(r_2 = m z_2 / 2\), where \(z_2\) is the number of teeth. The base circle radius is \(r_b = r_2 \cos \alpha\). The involute coordinates \((x, y)\) for a given roll angle \(u\) (in radians) are:

$$x = r_b (\sin u – u \cos u)$$

$$y = r_b (\cos u + u \sin u)$$

This involute defines one side of the tooth space. The other side is its mirror image. However, the three-dimensional form of the worm wheel tooth is not a simple extrusion; it is a helicoidal surface guided by the mating worm’s geometry. The guiding helix for the worm wheel tooth is a segment of the worm’s helix on the pitch cylinder. For a point on this helix, with the center distance \(a = r_1 + r_2\) and the worm’s lead angle \(\gamma\), the parametric equations in 3D space are:

$$x = a – r_1 \cos \theta$$

$$y = r_1 \sin \theta$$

$$z = r_1 \theta \tan \gamma$$

Here, \(\theta\) varies, typically over a range corresponding to the worm wheel’s wrap angle, such as from \(-\pi/2\) to \(\pi/2\) radians. This helix acts as the sweep path for the tooth profile, ensuring correct meshing with the screw gear partner.

To solidify these concepts, let’s consider a concrete example. I will design a screw gear pair with the following specifications: module \(m = 4 \text{ mm}\), worm diameter factor \(q = 10\), number of worm starts \(z_1 = 1\), number of worm wheel teeth \(z_2 = 40\), and center distance \(a = 100 \text{ mm}\). From these, we derive key dimensions, which are best summarized in a table.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value (mm or degrees) | Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Module | \(m\) | 4.0 | Given |

| Worm Pitch Diameter | \(d_1\) | 40.0 | \(d_1 = m q = 4 \times 10\) |

| Worm Reference Radius | \(r_1\) | 20.0 | \(r_1 = d_1 / 2\) |

| Worm Lead Angle | \(\gamma\) | \(21.8014^\circ\) | \(\gamma = \arctan(m z_1 / d_1)\) |

| Worm Wheel Pitch Diameter | \(d_2\) | 160.0 | \(d_2 = m z_2 = 4 \times 40\) |

| Worm Wheel Reference Radius | \(r_2\) | 80.0 | \(r_2 = d_2 / 2\) |

| Center Distance | \(a\) | 100.0 | \(a = r_1 + r_2\) |

| Axial Pitch | \(p_a\) | 12.5664 | \(p_a = \pi m\) |

| Addendum Height | \(h_a\) | 4.0 | \(h_a = h_a^* m = 1 \times 4\) |

| Dedendum Height | \(h_f\) | 4.8 | \(h_f = (h_a^* + c^*) m = (1+0.2) \times 4\) |

With these parameters defined, I proceed to SolidWorks 2010 for the 3D modeling. The process for the screw gear worm is relatively straightforward. First, I create the addendum cylinder as the base body. Next, I define a helix with a diameter equal to the worm’s pitch diameter \(d_1\). The pitch and number of revolutions are set based on the lead. The critical step is sketching the tooth groove cross-section. This sketch must lie in an axial plane. Using the equations for points 1, 2, 3, and 4, I draw the trapezoid representing one side of the thread space. Finally, I use the Swept Cut feature, using this sketch and the helix as the path, to generate a single thread groove. For a single-start worm, this completes the thread; for multi-start screw gears, a circular pattern would be applied. Additional features like shafts, bearings, or reliefs can then be added to complete the worm model. The accuracy of this screw gear model hinges on the precise definition of the trapezoidal profile and the helix.

The worm wheel modeling is more complex and embodies the true challenge in screw gear design. The flowchart of the process involves creating the wheel blank, generating the helical guide curves, constructing the involute tooth profile in the middle plane, performing a swept cut along the helix, and finally patterning the tooth space. Creating the wheel blank—a cylindrical body with a hub and web—is simple. The guide helix is created using the 3D curve tool, inputting the parametric equations for \(x(\theta)\), \(y(\theta)\), and \(z(\theta)\). Since the worm wheel tooth is only engaged over a portion of the worm’s circumference, I generate two helical segments, one on each side of the middle plane.

The most intricate part is defining the tooth space profile. SolidWorks 2010 offers an “Equation Driven Curve” tool, which I use to plot the involute. I set the parameters: \(r_b = r_2 \cos \alpha = 80 \cos(20^\circ) \approx 75.175 \text{ mm}\). In the dialog, I input the parametric equations for the involute’s X and Y components as functions of a parameter \(t\) (representing the roll angle \(u\)). The range for \(t\) starts at 0 and extends to a value whose corresponding radius is slightly larger than the worm wheel’s addendum radius to ensure the full tooth flank is captured. After generating this curve, I need to position it correctly. The involute generated from the base circle starts at a point on that circle. For proper symmetry, I rotate this curve by an angle \(\theta_0\) calculated as:

$$\theta_0 = \phi – (\tan \alpha – \alpha \text{ [in radians]})$$

where \(\phi = \frac{\pi}{2 z_2}\) accounts for the half-tooth-space angle. This rotation aligns the curve so that its mirror image across the vertical axis creates the other side of the tooth space. I then sketch the addendum circle (radius \(r_{a2} = r_2 + h_a\)) and the dedendum circle (radius \(r_{f2} = r_2 – h_f\)), trim them with the two involute segments, and add a fillet at the root to simulate the tool tip radius, typically around \(2 \text{ mm}\) in this case. This closed contour is the tooth space profile. Now, using the Swept Cut feature, I select this profile and one of the helical curves as the path, with the option “Twist along path” set to “Follow Path” to maintain orientation. This creates one tooth gap. I then use a Circular Pattern feature to replicate this cut \(z_2 = 40\) times around the axis, generating all teeth. Finally, I add detailed features like keyways, bolt holes, or rim contours to finalize the screw gear wheel.

The assembly of the screw gear pair in SolidWorks is straightforward but requires careful attention to mating conditions. I begin a new assembly document. First, I insert the worm wheel part. Then, I insert the worm part. To define their spatial relationship correctly, I add a reference axis along the worm’s rotational axis in the worm part. In the assembly, I mate this axis to a constructed line or axis in the worm wheel part that represents the theoretical position of the worm axis, which is offset by the center distance \(a\) from the worm wheel axis. Specifically, I create a sketch line in the worm wheel part file at a distance \(a\) from its axis. In the assembly, I apply a Coincident mate between the worm’s axis and this line. Next, I ensure the worm’s middle plane aligns with the worm wheel’s middle plane using a Distance mate set to zero. Finally, I adjust the rotational position of the worm so that a thread is properly engaged with a tooth space. This establishes the correct meshing position for the screw gear set. After mating, I run an Interference Detection check to ensure no unwanted geometric clashes exist, which is vital for verifying the design of any screw gear system.

The parametric nature of this SolidWorks model cannot be overstated. By linking sketch dimensions and feature parameters to global variables (like \(m\), \(z_1\), \(z_2\), \(q\)), I can modify the entire screw gear design by changing just a few input values. This flexibility is invaluable for exploring different screw gear configurations and optimizing performance. For instance, adjusting the diameter factor \(q\) affects the worm’s stiffness and the lead angle, thereby influencing the screw gear’s efficiency and load capacity. The 3D model automatically updates, and the assembly mates remain intact. This parametric capability extends to generating drawings, calculating mass properties, and performing simulations.

To further illustrate the mathematical backbone, let’s recap the core equations governing this screw gear pair. The worm axial profile is defined by linear equations based on the trapezoid. The worm wheel involute is defined by the parametric involute equations. The guiding helix for the worm wheel sweep is derived from the worm’s kinematics. These equations are interrelated through the fundamental screw gear parameters. Another useful formula is the lead of the worm, \(L = \pi d_1 \tan \gamma = \pi m z_1\), which determines the axial advance per revolution. For the example screw gear, \(L = \pi \times 4 \times 1 = 12.566 \text{ mm}\). The velocity ratio of the screw gear set is \(i = z_2 / z_1 = 40\), meaning the worm wheel rotates one revolution for every forty revolutions of the worm, providing high reduction ratios in a compact space, a hallmark advantage of screw gear drives.

In practical applications, screw gears often require lubrication and careful thermal design due to sliding contact. The 3D model facilitates the design of housing, oil passages, and cooling fins. Furthermore, the accurate geometric model is essential for finite element analysis (FEA) to assess stress concentrations, especially at the root of the worm wheel teeth and in the worm shaft. With the SolidWorks model, I can directly apply forces derived from torque transmission and perform static or dynamic stress analysis. Motion simulation can also be conducted to study the engagement dynamics, contact patterns, and potential vibrations in the screw gear system. These advanced analyses rely heavily on the precision of the initial 3D model.

Throughout this modeling exercise, the term ‘screw gear’ has been central. A screw gear pair is essentially a specific type of gear where the worm resembles a screw thread. The design and manufacturing of screw gears demand high precision to ensure smooth operation and longevity. The Archimedes type, with its straight-sided axial profile on the worm, is one of the simplest to model and manufacture, making it a common choice for many industrial screw gear applications. Other types, like involute or convolute worms, have different profile generation methods but share the same fundamental screw gear principle of crossed-axis helical motion transmission.

To summarize the entire process in a procedural table:

| Step | Component | Key Actions in SolidWorks | Governing Equations/Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parameter Definition | Both | Set global variables (m, q, z1, z2, a) | \(m, q, z_1, z_2, a = r_1 + r_2\) |

| 2. Worm Modeling | Worm (Screw) | Create cylinder, sketch trapezoid, create helix, swept cut. | Axial profile points: \(x_1, y_1, x_3, y_3\); Helix lead angle \(\gamma\). |

| 3. Worm Wheel Modeling | Wheel (Gear) | Create blank, create 3D helix curves, sketch involute using equation-driven curve, swept cut, circular pattern. | Involute: \(x(u), y(u)\); Guide helix: \(x(\theta), y(\theta), z(\theta)\). |

| 4. Detailing | Both | Add features: shafts, keyways, fillets, chambers. | Standard mechanical design rules. |

| 5. Assembly | Screw Gear Pair | Insert parts, mate worm axis to offset line in wheel, align middle planes. | Center distance \(a\); Coincident and distance mates. |

| 6. Verification | Assembly | Run interference detection, check motion. | Geometric clearance checks. |

The advantages of this SolidWorks-based approach for screw gear design are multifaceted. It enables rapid prototyping and visualization, reducing the need for physical prototypes. Changes can be made swiftly, and different design iterations of the screw gear can be compared easily. The 3D model serves as a single source of truth for manufacturing drawings, CAM programming, and technical documentation. Moreover, the digital twin of the screw gear pair can be integrated into larger assembly models to verify fit and function within a complete machine.

In conclusion, the meticulous modeling and assembly of Archimedes screw gears using SolidWorks, as detailed from my perspective, demonstrate a robust methodology that blends classical gear theory with modern CAD tools. The parametric equations for the worm profile, the worm wheel involute, and the helical path are seamlessly translated into precise 3D geometry. This process not only ensures design accuracy for the screw gear components but also unlocks advanced engineering analysis capabilities. As screw gears continue to be vital in applications requiring compact, high-ratio power transmission, mastering such parametric modeling techniques becomes indispensable for engineers aiming to innovate and optimize mechanical systems efficiently. The entire exercise underscores the power of integrating mathematical fundamentals with sophisticated software to tackle complex mechanical design challenges like those presented by screw gears.