In my extensive experience in gear manufacturing, I have often encountered the need for precision screw gears, particularly those with variable tooth thickness. These screw gears, also known as dual-lead worm gears, are fascinating components where the tooth thickness varies axially, allowing for adjustable backlash without altering the center distance. This feature makes them invaluable in various mechanical applications, from machine tools to aerospace systems. In this article, I will delve into the detailed machining processes for variable tooth thickness screw gears, sharing insights from my hands-on work. I will use formulas and tables to summarize key concepts, ensuring a comprehensive understanding. Throughout, I will frequently refer to screw gears to emphasize their importance in this context.

The fundamental principle behind variable tooth thickness screw gears lies in the differential lead between the left and right tooth flanks of the worm. Specifically, the worm has two distinct leads: one for the left flank and another for the right flank. This results in a tooth thickness that increases or decreases along the axial direction, enabling precise control over meshing clearance. Mathematically, the lead for a standard worm is given by $$ P = \pi \cdot m \cdot z $$ where \( P \) is the lead, \( m \) is the module, and \( z \) is the number of starts. For a variable tooth thickness worm, we define two leads: \( P_L \) for the left flank and \( P_R \) for the right flank. The difference in leads, \( \Delta P = |P_L – P_R| \), dictates the rate of tooth thickness variation. This can be expressed as $$ \Delta t = \frac{\Delta P}{2\pi} \cdot L $$ where \( \Delta t \) is the change in tooth thickness over axial length \( L \). This simple yet powerful concept underpins the machining of these screw gears.

When machining a variable tooth thickness worm, the process begins with cutting a straight groove using a tool whose width is less than the minimum root width of the worm. This is done based on the nominal lead, which is typically the average of the left and right leads. For instance, if the nominal lead is \( P_n = 10 \, \text{mm} \), the left lead is \( P_L = 9.8 \, \text{mm} \), and the right lead is \( P_R = 10.2 \, \text{mm} \), the nominal lead serves as a reference for initial setup. I often use a gear hobbing or threading machine for this purpose,搭配交换挂轮 (change gears) to achieve the desired lead. The change gear ratio is critical and can be calculated using the machine’s transmission formula. For example, on a typical lathe or milling machine, the relationship is $$ i = \frac{P_{\text{worm}}}{P_{\text{lead screw}}} \cdot \frac{A}{B} \cdot \frac{C}{D} $$ where \( i \) is the overall transmission ratio, \( P_{\text{worm}} \) is the worm lead, \( P_{\text{lead screw}} \) is the lead screw pitch, and \( A, B, C, D \) are the change gears. Table 1 summarizes common parameters for machining a variable tooth thickness screw gear worm.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal Module | \( m_n \) | 2 | mm |

| Number of Starts | \( z \) | 1 | – |

| Nominal Lead | \( P_n \) | 6.283 | mm |

| Left Flank Lead | \( P_L \) | 6.183 | mm |

| Right Flank Lead | \( P_R \) | 6.383 | mm |

| Axial Length | \( L \) | 100 | mm |

| Tooth Thickness Variation | \( \Delta t \) | 3.183 | mm |

After cutting the straight groove, I proceed to machine the left and right flanks separately. This requires adjusting the change gears according to the specific leads. For the left flank, the change gear ratio \( i_L \) is computed as $$ i_L = \frac{P_L}{P_{\text{lead screw}}} \cdot K $$ where \( K \) is a constant specific to the machine. Similarly, for the right flank, $$ i_R = \frac{P_R}{P_{\text{lead screw}}} \cdot K $$. In practice, I consult the machine’s change gear table to select the appropriate gears. For example, if \( P_{\text{lead screw}} = 6 \, \text{mm} \) and \( K = 1 \), then \( i_L = \frac{6.183}{6} \approx 1.0305 \) and \( i_R = \frac{6.383}{6} \approx 1.0638 \). These ratios are achieved by combining gears such as 30/29 and 67/63, respectively. Table 2 provides a sample change gear setup for a common machine.

| Flank | Lead (mm) | Desired Ratio | Gear Combination (A/B × C/D) | Actual Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | 6.183 | 1.0305 | 30/29 × 40/39 | 1.0306 |

| Right | 6.383 | 1.0638 | 67/63 × 50/47 | 1.0639 |

The machining of the worm requires careful alignment and tool positioning. I use a tool with a profile that matches the desired tooth shape, often a single-point threading tool for precision. The depth of cut is gradually increased to form the flanks. During this process, I constantly verify the lead using a lead tester or optical comparator. The variable tooth thickness screw gear worm is thus produced with high accuracy, ensuring smooth operation when paired with its corresponding wheel.

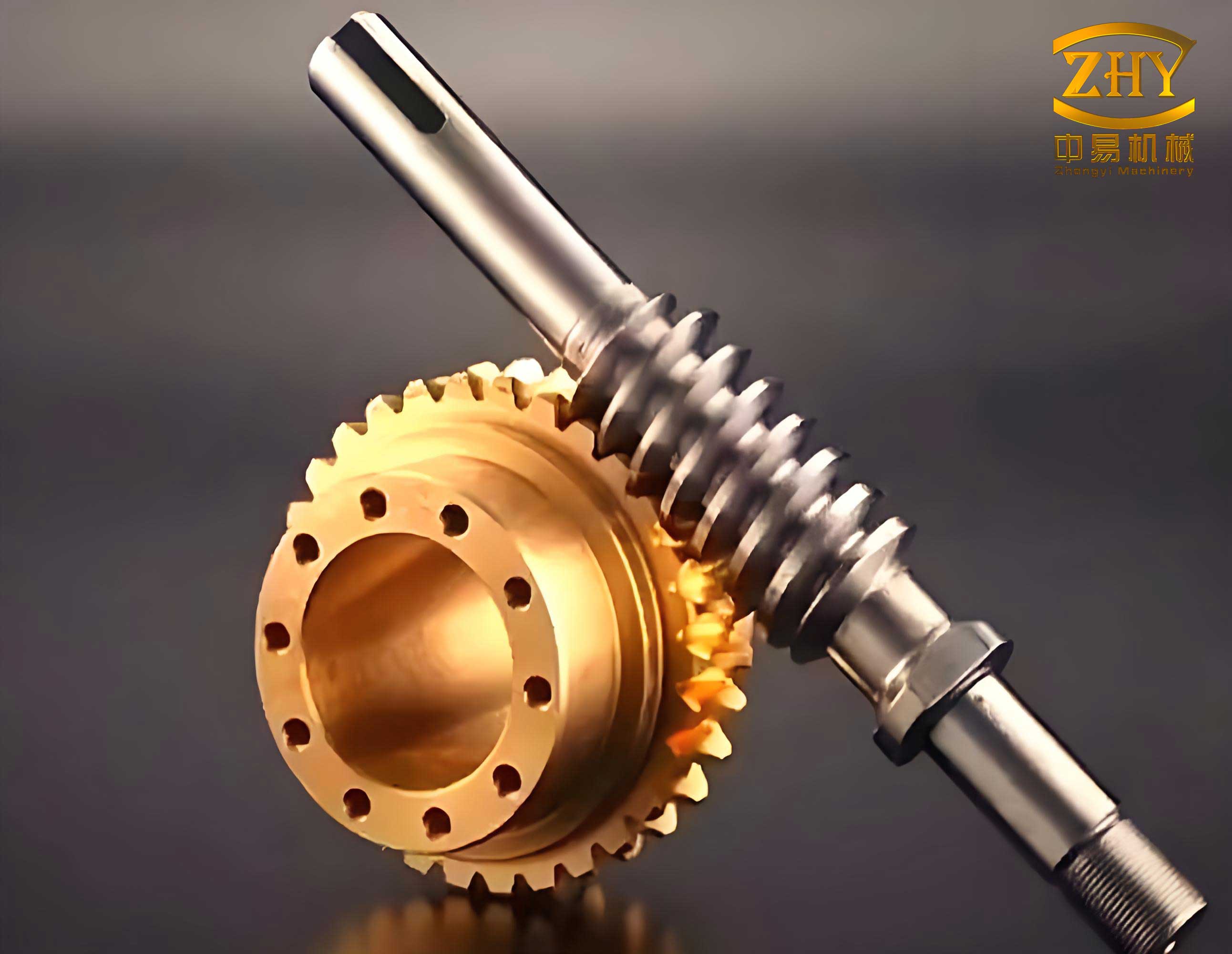

Now, turning to the worm wheel, which is the mating component in a screw gear pair. Machining a variable tooth thickness worm wheel is more complex than a standard worm wheel because the tooth shape must conform to the worm’s varying thickness. In my practice, I employ a dedicated hob that mirrors the worm’s geometry. This hob has the same left and right leads and helix angles as the worm. The key is to align the hob’s tooth thickening direction with the worm’s tooth thickening direction during installation. This ensures proper meshing and backlash adjustment. The setup is illustrated in the following image, which shows a typical arrangement for machining a screw gear wheel.

As seen, the hob is mounted on the machine spindle, and the worm wheel blank is fixed on the worktable. The hob’s axis is inclined at the helix angle \( \beta \), which matches that of the worm. The helix angle is related to the lead and pitch diameter by $$ \tan \beta = \frac{P}{\pi \cdot d} $$ where \( d \) is the pitch diameter. For a variable tooth thickness screw gear, the helix angle differs between flanks, but the hob accommodates this by having corresponding profiles. I begin by centering the hob using its standard tooth, then adjust the center height with gauge blocks. Radial feed is applied to cut the teeth progressively. The feed rate \( f_r \) is calculated based on the module and number of teeth: $$ f_r = \frac{m_n \cdot \pi}{z_w} $$ where \( z_w \) is the number of teeth on the worm wheel. Table 3 outlines key parameters for worm wheel machining.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheel Module | \( m_n \) | 2 | mm |

| Number of Teeth | \( z_w \) | 30 | – |

| Pitch Diameter | \( d_w \) | 60 | mm |

| Helix Angle (Left) | \( \beta_L \) | 4.5 | degrees |

| Helix Angle (Right) | \( \beta_R \) | 4.7 | degrees |

| Hob Lead (Left) | \( P_{hL} \) | 6.183 | mm |

| Hob Lead (Right) | \( P_{hR} \) | 6.383 | mm |

An alternative method involves using two hobs with different helix angles to cut the left and right flanks separately. This approach is useful for high-precision screw gears, as it allows independent control over each flank. I have also used fly tools for small batches, where dedicated hobs are not economical. The fly tool is essentially a single-point tool mounted on a fly cutter, and it follows the same principle as the hob but with slower production rates. The cutting speed \( V_c \) for hobbling is given by $$ V_c = \frac{\pi \cdot d_h \cdot N}{1000} $$ where \( d_h \) is the hob diameter and \( N \) is the spindle speed in RPM. For a fly tool, the speed is lower, and the feed is manual, but the accuracy can be excellent with skilled operation.

The mathematics behind variable tooth thickness screw gears is rich and involves advanced geometry. The tooth profile is typically involute, but with modifications due to the varying lead. The pressure angle \( \alpha \) also changes along the tooth. For a standard screw gear, the pressure angle is constant, but here, it can be derived from the lead difference. Using the fundamental law of gearing, the condition for conjugate action is $$ \frac{\tan \alpha_L}{\tan \alpha_R} = \frac{P_L}{P_R} $$ where \( \alpha_L \) and \( \alpha_R \) are the pressure angles for left and right flanks. This relation ensures smooth transmission of motion. In practice, I design the screw gear pair using CAD software, but understanding these equations helps in troubleshooting machining issues.

Backlash adjustment is a prime advantage of variable tooth thickness screw gears. By axially shifting the worm, the meshing clearance can be fine-tuned without disassembling the assembly. The backlash \( B \) is related to the axial shift \( \Delta x \) by $$ B = \Delta x \cdot \frac{\Delta P}{P_n} $$ where \( \Delta P \) is the lead difference. For instance, if \( \Delta P = 0.2 \, \text{mm} \), \( P_n = 6.283 \, \text{mm} \), and \( \Delta x = 1 \, \text{mm} \), then \( B = 1 \cdot \frac{0.2}{6.283} \approx 0.0318 \, \text{mm} \). This small adjustment capability is crucial in applications like robotics and precision instruments, where minimal play is desired. I often incorporate adjusting mechanisms, such as shims or eccentric sleeves, to facilitate this during assembly.

In terms of material selection, screw gears are typically made from hardened steel for the worm and bronze or cast iron for the wheel to reduce friction and wear. I recommend case-hardening steels like 20MnCr5 for the worm and phosphor bronze for the wheel. The heat treatment process must be controlled to avoid distortion, which can affect the variable tooth thickness profile. After machining, I perform grinding or honing to achieve the final surface finish. For high-end screw gears, I use CNC grinding machines with adaptive controls to maintain the lead accuracy across the length.

Quality control is paramount in screw gear manufacturing. I use coordinate measuring machines (CMM) to verify tooth thickness, lead, and helix angle. The measurement data is compared against the design specifications. For variable tooth thickness screw gears, I take multiple sections along the axial length and plot the thickness variation. The profile deviation \( \delta_t \) should be within tolerance, say ±0.01 mm. Additionally, I conduct backlash tests by rotating the worm and measuring the angular play on the wheel. This ensures the screw gear pair meets performance requirements.

From an application perspective, variable tooth thickness screw gears are found in indexing heads, rotary tables, and steering systems. Their ability to adjust backlash makes them ideal for systems subject to wear over time. In my career, I have supplied these screw gears to machine tool builders, where they enhance positioning accuracy. The design flexibility allows for custom leads and thickness profiles, catering to specific motion control needs.

To further elaborate on the machining process, let’s consider a detailed case study. Suppose I need to produce a screw gear pair for a CNC rotary axis. The worm has a nominal module of 2.5 mm, left lead of 7.854 mm (corresponding to \( \pi \cdot m \cdot z \) with \( z=1 \)), and right lead of 8.054 mm. The wheel has 40 teeth. The machining steps are as follows: First, I set up the lathe with change gears for the nominal lead of 7.954 mm. I cut a straight groove 3 mm wide using a tool with a 2 mm width. Then, I change gears for the left lead and machine the left flank with a depth of cut of 0.5 mm per pass until the full depth of 5.5 mm is reached. I repeat for the right flank with its respective change gears. For the wheel, I use a dedicated hob with leads of 7.854 mm and 8.054 mm. I mount the hob at a helix angle of $$ \beta = \arctan\left(\frac{P_n}{\pi \cdot d_w}\right) = \arctan\left(\frac{7.954}{\pi \cdot 100}\right) \approx 4.55^\circ $$ where \( d_w = m_n \cdot z_w = 2.5 \cdot 40 = 100 \, \text{mm} \). I then perform radial hobbing with a feed of 0.1 mm per revolution. After cutting, I deburr and heat-treat the components. The final assembly shows negligible backlash after axial adjustment.

The economic aspects of producing variable tooth thickness screw gears cannot be ignored. Dedicated hobs are expensive, so for small batches, I opt for fly cutting or CNC milling with custom tools. The setup time is longer, but the tooling cost is lower. For large volumes, investing in a dedicated hob is justified due to faster cycle times. I always conduct a cost-benefit analysis before deciding on the machining method. Moreover, the scrap rate is higher for these screw gears due to their complexity, so process control is essential.

In conclusion, machining variable tooth thickness screw gears is a specialized field that combines precise engineering with practical craftsmanship. Through careful calculation of leads, change gear selection, and proper tool alignment, I can produce high-quality screw gears that offer adjustable backlash and reliable performance. The use of formulas and tables, as shown in this article, aids in standardizing the process. As technology advances, CNC methods are becoming more prevalent, but the fundamental principles remain. I encourage gear manufacturers to explore these screw gears for applications demanding precision and adaptability. The future may see integration with smart manufacturing, where real-time monitoring adjusts machining parameters for optimal results. Regardless, the variable tooth thickness screw gear will continue to be a cornerstone in mechanical transmission systems.

Finally, I want to stress the importance of continuous learning in this field. As I work on screw gears, I often collaborate with designers to optimize profiles for noise reduction and efficiency. The interplay between theory and practice enriches my understanding, and I hope this article provides valuable insights for others involved in screw gear manufacturing. Remember, the key to success lies in attention to detail, from initial design to final inspection. With that, I conclude this comprehensive guide on machining variable tooth thickness screw gears.