The transmission of motion and power between non-intersecting, perpendicular shafts is a fundamental requirement in many mechanical systems. Among the various solutions available, screw gears, commonly referred to as worm and worm wheel drives, occupy a critical niche. These drives are characterized by their compact design, high single-stage reduction ratios, smooth and quiet operation, and the potential for self-locking. These attributes make them indispensable in applications ranging from precision machine tools and indexing heads to heavy-duty lifting equipment and automotive steering systems. However, the very nature of their contact—a sliding, line contact between the screw gear (worm) thread and the worm wheel tooth—subjects them to significant cyclic stresses. Under prolonged operational loads, this can lead to fatigue failure, a primary mode of mechanical failure that initiates at stress concentrations and propagates until catastrophic fracture occurs. Predicting and understanding this fatigue behavior is therefore paramount for ensuring reliability, safety, and optimal design. This work presents a comprehensive numerical investigation into the fatigue life of screw gears, employing a modern simulation workflow that integrates dynamic multibody analysis with advanced fatigue calculation methods.

The core challenge in analyzing screw gears lies in accurately capturing the complex, time-varying load distribution across the highly non-linear contact surfaces during motion. Traditional static or quasi-static finite element analysis often fails to account for dynamic effects, inertial forces, and the true history of stress variation experienced by each point on the gear teeth. To overcome this limitation, the methodology adopted here leverages the concept of rigid-flexible coupling dynamics. This approach involves creating a dynamic model where the housing and shafts can be treated as rigid bodies, while the critical components—the screw gear and the worm wheel—are transformed into flexible bodies with their inherent material elasticity and damping properties. This allows for a simulation that is both computationally efficient and physically accurate, revealing the dynamic stress and strain fields throughout the engagement cycle.

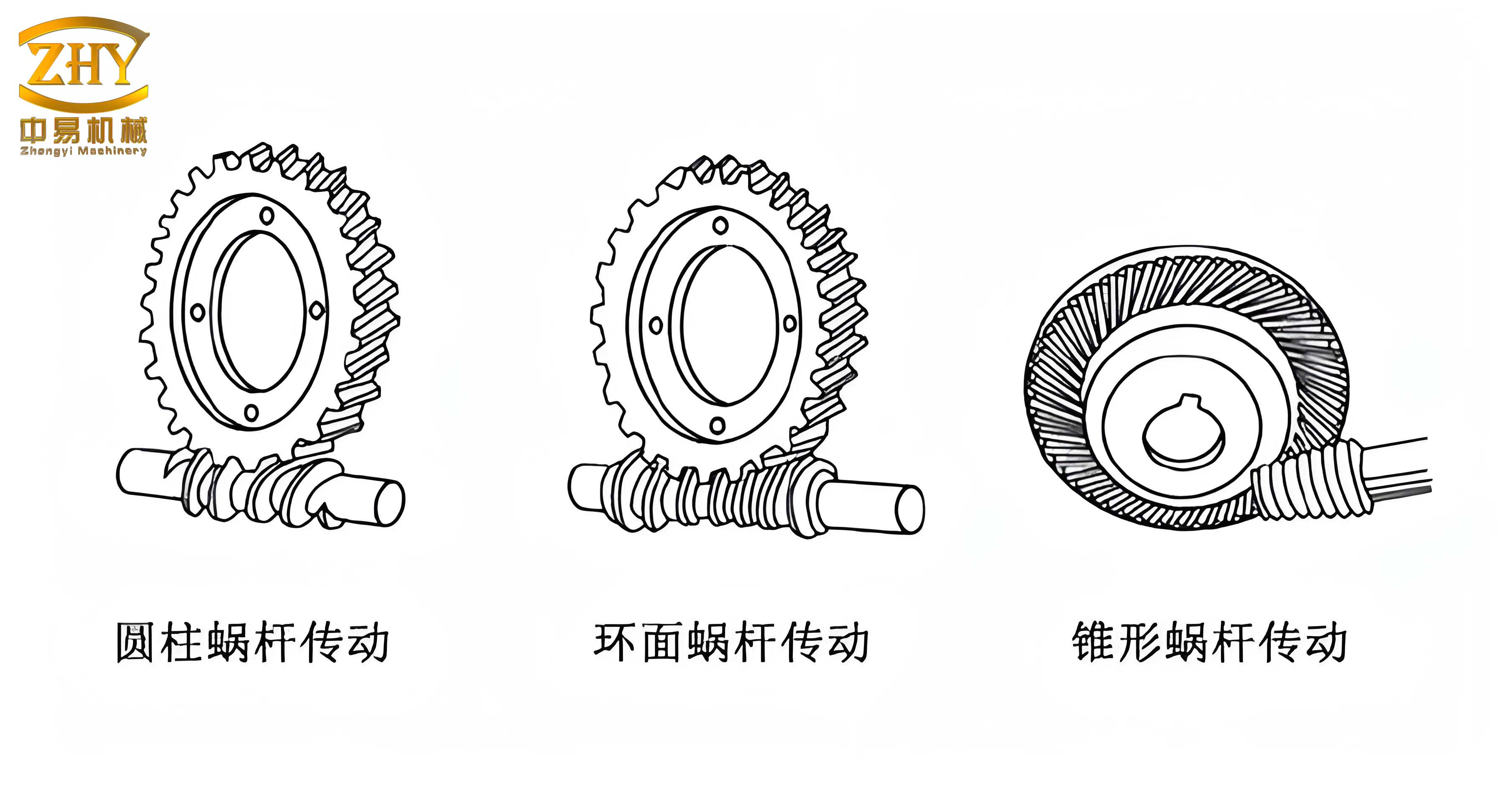

The initial phase of this study focuses on the geometric and material definition of the screw gear pair. Screw gears are classified based on the geometry of the worm thread. Common types include the Archimedean (ZA), involute (ZI), and convolute (ZN) worms. For this analysis, a ZN-type (straight-sided normal section) screw gear set is modeled, as its generation is well-defined and it finds common industrial use. The primary design parameters for the modeled screw gears are summarized in the table below:

| Parameter | Screw Gear (Worm) | Worm Wheel |

|---|---|---|

| Module (mm) | 1 | 1 |

| Number of Threads/Teeth | 2 | 43 |

| Pressure Angle (°) | 12 | 12 |

| Lead Angle (°) | 6° 22′ 6″ | – |

| Helix Angle (°) | – | 11° 18′ 36″ |

| Type / Grade | ZN, Grade 8 | Conjugate to ZN |

A precise three-dimensional solid model is created based on these parameters using computer-aided design (CAD) software. The material properties assigned to the components are critical for both the dynamic and subsequent fatigue analysis. The screw gear, subject to higher contact stresses and wear, is typically made of a hardened steel, while the worm wheel is often made from a softer, often non-metallic material like cast bronze or engineered polymers to reduce friction and wear. The properties used in this simulation are:

| Component | Material | Yield Strength, $\sigma_y$ (MPa) | Young’s Modulus, $E$ (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio, $\nu$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screw Gear (Worm) | 40Cr Steel | 785 | 210 | 0.3 |

| Worm Wheel | Polyamide (Nylon) | 150 | 6.0 | 0.4 |

The central technique of this study is the rigid-flexible coupling simulation. The CAD model is imported into a specialized multi-body dynamics (MBD) software, RecurDyn. Here, kinematic joints (revolute joints) are applied to the shafts of both the screw gear and the worm wheel to define their rotational degrees of freedom. A contact force algorithm is defined between the tooth surfaces of the screw gear and the worm wheel, typically using a penalty-based method with appropriate stiffness and damping coefficients to model the elastic impact and friction. The key step is the generation of flexible bodies. Using the Finite Element Analysis (FEA) co-simulation module within RecurDyn (F-Flex), the solid models of the screw gear and the worm wheel are individually meshed with finite elements. The mesh is refined in the tooth contact regions to capture stress gradients accurately. The result is a .mnf (Modal Neutral File) for each component, which contains its mass, stiffness, and mode shape information. In the final dynamic model, these flexible bodies replace their rigid counterparts. A constant angular velocity is applied to the input screw gear shaft, and the worm wheel shaft is subjected to a realistic resistive torque load simulating operational conditions. The simulation is run for a sufficient number of revolutions to capture steady-state dynamic behavior.

The output of the rigid-flexible coupling analysis is a time-history of stress, strain, and deformation for every node in the finite element mesh of the flexible screw gear and worm wheel. The stress contours (cloud plots) at critical instants provide immediate visual insight. For the steel screw gear, the maximum von Mises stress is observed to be approximately 126 MPa, located near the root and tip regions of the thread. Although this value is well below the material’s yield strength (785 MPa), it signifies a stress concentration. For the polymer worm wheel, the maximum stress, around 109 MPa, is concentrated at the tooth root fillet area. The cyclical application of this stress, once per tooth engagement, is the driving force for fatigue damage initiation. The dynamic analysis confirms that the most critically loaded zones in screw gears are the root of the worm wheel teeth and the root/tip of the screw gear threads, acting as potential initiation sites for fatigue cracks.

To transition from dynamic stress data to a prediction of service life, a fatigue analysis framework is essential. Fatigue life ($N_f$) is defined as the number of stress cycles a component can endure before failure. It is primarily governed by the stress range ($\Delta \sigma$), mean stress ($\sigma_m$), and the material’s fatigue properties. For high-cycle fatigue (HCF), where stresses are largely elastic and failure occurs at cycles typically greater than $10^4$, the material behavior is best described by an S-N curve (Wöhler curve). The relationship between the alternating stress amplitude ($\sigma_a$) and the number of cycles to failure ($N_f$) is often expressed using Basquin’s equation:

$$

\sigma_a = \sigma_f’ (2N_f)^b

$$

where $\sigma_f’$ is the fatigue strength coefficient and $b$ is the fatigue strength exponent (Basquin’s exponent). The mean stress effect is frequently corrected using models like the Goodman or Gerber rule. For the screw gear made of steel, standard S-N data for 40Cr steel can be applied. For the polymer worm wheel, the fatigue behavior is more complex and highly sensitive to frequency, temperature, and mean stress, requiring specialized S-N curves for polyamide under relevant conditions.

In this work, the fatigue life calculation is performed using the specialized software FEMFAT. The process is a two-step hybrid approach: First, the transient stress result files (the “load collective”) and the flexible body mesh files from the RecurDyn simulation are imported into FEMFAT. Second, the material S-N curves, along with necessary correction factors for surface finish, size, reliability (here set to a standard 97.5% survival probability), and stress concentration (notch sensitivity), are applied. FEMFAT then performs a post-processing fatigue analysis using the stress-time history from every node in the mesh. It calculates the damage accumulation based on a linear Palmgren-Miner rule:

$$

D = \sum_{i=1}^{k} \frac{n_i}{N_{f,i}}

$$

where $D$ is the total accumulated damage, $n_i$ is the number of cycles at a specific stress level $i$, and $N_{f,i}$ is the cycles to failure at that stress level read from the S-N curve. Failure is predicted when $D \geq 1$. The primary outputs are contour plots of fatigue life (in cycles) and safety factor ($SF$). The safety factor, in the context of fatigue, is often defined as the ratio of the enduring limit (or a life-based strength) to the working stress amplitude, considering mean stress effects. A safety factor less than 1.0 indicates a finite life expectation at the target cycle count.

The fatigue analysis yields critical quantitative insights. For the steel screw gear, the predicted life at the target load level is approximately $4.88 \times 10^5$ cycles. The safety factor distribution map shows that over 99.99% of the nodes have an $SF > 1$, indicating a high overall design margin. However, a very small fraction of nodes (about 0.01%), precisely located at the thread root and tip stress concentration zones, exhibit an $SF < 1$. These are the “hot spots” or critical nodes where fatigue crack initiation is most probable. Similarly, for the polyamide worm wheel, the predicted life is around $5.03 \times 10^5$ cycles. Here, about 99.97% of the nodes are safe, while 0.03% of the nodes, overwhelmingly concentrated in the tooth root fillet region, show an $SF < 1$. This finding is consistent with the dynamic stress analysis and reinforces the tooth root as the Achilles’ heel of the worm wheel in screw gear sets under cyclic loading.

The congruence between the high-stress zones identified in the rigid-flexible coupling analysis and the low-safety-factor zones in the fatigue analysis is significant. It validates the simulation workflow and pinpoints the root cause of potential fatigue failure in screw gears: **stress concentration due to geometric notches (root fillets) and localized high contact pressure**. The sliding action in screw gears exacerbates this by potentially causing friction-induced tensile stresses on the trailing edges of the teeth. For the steel screw gear, the failure mode would typically be subsurface-originated pitting or bending fatigue crack initiation at the root. For the polymer worm wheel, the failure could involve cyclic plastic deformation, heat generation (hysteresis), and ultimately crack initiation and growth in the root area.

The implications for design optimization are direct and substantial. The analysis provides a clear map of where material is under-utilized and where it is critically stressed. Potential optimization strategies for enhancing the fatigue life of screw gears include:

- Geometric Optimization: Redesigning the tooth profile, increasing the root fillet radius, or applying tip relief to reduce stress concentration factors. The optimal profile can be iteratively explored using this simulation framework.

- Material Selection/ Treatment: For the screw gear, using steels with higher fatigue strength or applying surface treatments like shot peening or nitriding to introduce beneficial compressive residual stresses in the root region. For the worm wheel, selecting polyamide grades with higher fatigue endurance limits or reinforced composites.

- Load Management: Ensuring proper alignment, improving lubrication to reduce friction and associated tensile stresses, and avoiding shock loads can dramatically increase the operational life predicted by the model.

This integrated methodology—combining high-fidelity rigid-flexible coupling dynamics for load history generation with spectral fatigue analysis—offers a powerful virtual prototyping tool. It moves beyond the limitations of static analysis and handbook calculations for screw gears. While physical testing remains the ultimate validation, this numerical approach allows for the rapid exploration of design variants, identification of failure modes, and life prediction under complex loading conditions long before a physical prototype is built. It is particularly valuable for custom or highly loaded screw gear applications where standard design rules may be insufficient.

In conclusion, this study successfully demonstrates a procedural framework for the fatigue life assessment of screw gears. The use of rigid-flexible coupling dynamics provided an accurate, time-dependent load spectrum that captures the true dynamic interaction between the screw gear and worm wheel. Subsequent fatigue analysis using this load data identified the precise locations of vulnerability: the root and tip of the screw gear threads and the root of the worm wheel teeth. The predicted safety factor maps and life estimates offer a quantitative basis for design decisions. Future work could extend this analysis to include thermal effects from friction, more advanced multi-axial fatigue criteria, and the simulation of full crack propagation using fracture mechanics principles. Furthermore, the validation of these numerical predictions against controlled physical fatigue tests on screw gear sets would be a logical and valuable next step to fully calibrate and confirm the reliability of this virtual engineering workflow for power transmission components.