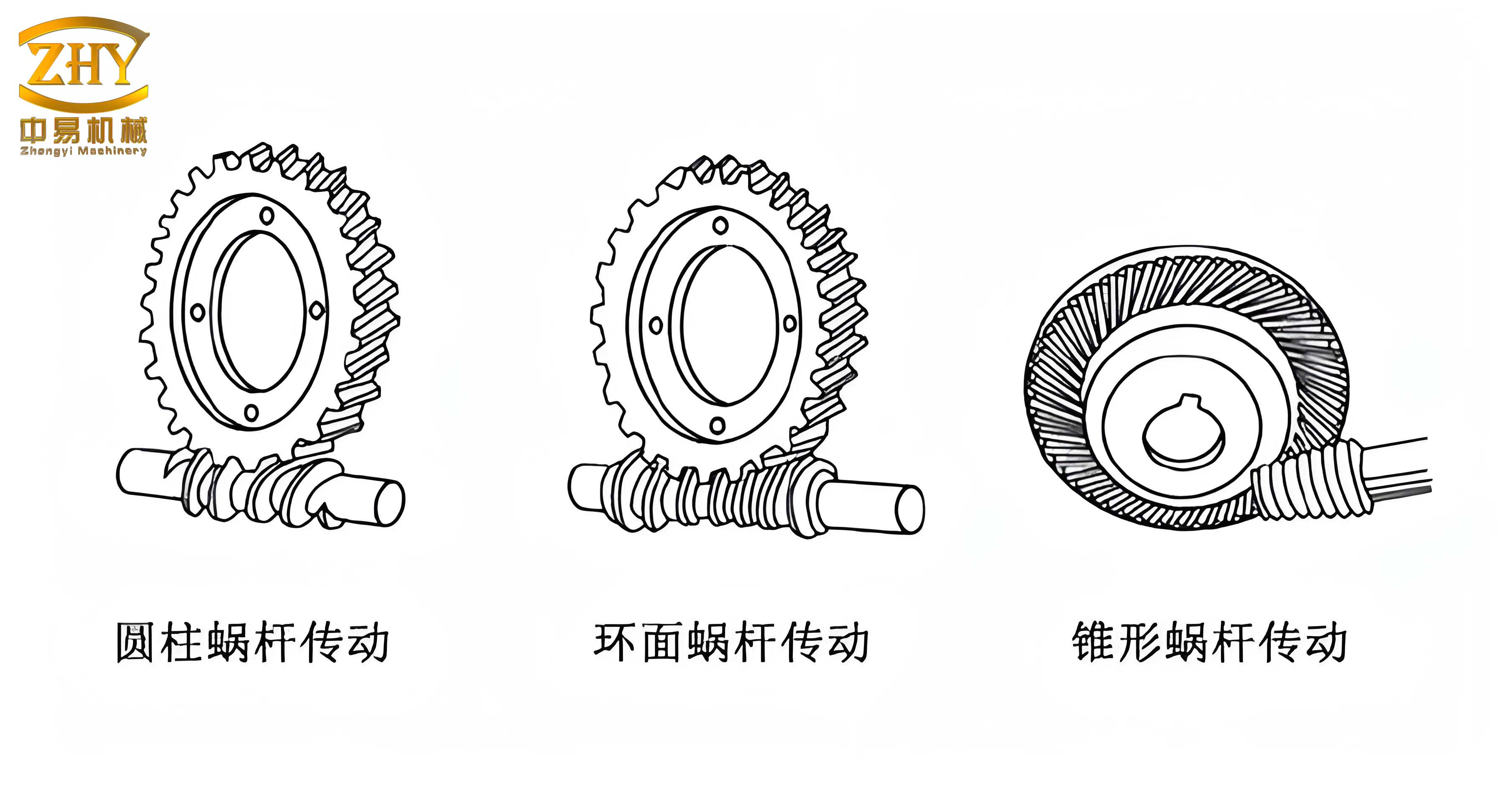

In mechanical transmission systems, screw gears, such as worm drives, play a crucial role due to their high reduction ratios and compact design. However, the lubrication performance between meshing surfaces significantly influences their efficiency, durability, and reliability. Elastohydrodynamic lubrication (EHL) theory is essential for understanding the formation of lubricant films under high pressure and elastic deformation. In real-world applications, surface roughness is inevitable due to manufacturing processes, and its impact on EHL cannot be neglected when the roughness amplitude is comparable to the oil film thickness. This study focuses on the EHL analysis of an inclined double-roller enveloping hourglass worm drive, a novel type of screw gear transmission, considering surface roughness effects. The goal is to investigate how roughness peaks and valleys influence the oil film pressure and thickness, and to analyze the lubrication characteristics at different meshing points from engagement to disengagement. Furthermore, the effects of key design parameters, such as roller radius, throat diameter coefficient, and roller offset distance, on EHL performance are examined to provide insights for optimizing screw gear designs.

Screw gears, including worm drives, are widely used in heavy-duty applications where sliding and rolling contacts occur between conjugate surfaces. The inclined double-roller enveloping hourglass worm drive features a unique configuration where rollers replace traditional worm wheel teeth, reducing sliding friction and improving transmission accuracy. This design involves two rows of rollers offset to eliminate backlash, enhancing stability. However, the complex contact geometry and multi-tooth meshing process pose challenges for lubrication analysis. In EHL, the lubricant film thickness is often on the order of micrometers, similar to surface roughness from grinding processes, making it necessary to incorporate roughness into the models. Previous studies on screw gear lubrication have often assumed smooth surfaces, but this simplification may lead to inaccurate predictions in practical scenarios. Therefore, this work develops a line-contact EHL model that accounts for single roughness peaks and valleys on the conjugate surfaces, using Newtonian fluid assumptions and numerical methods to solve the governing equations.

The meshing process of screw gears, particularly in worm drives, involves instantaneous multi-tooth contact with spatial contact lines. For the inclined double-roller enveloping hourglass worm drive, the equivalent curvature radius, entrainment velocity, and load per unit length vary along the meshing path. These parameters are critical for EHL analysis. The equivalent curvature radius \( R \) is derived from the induced normal curvature, as given by:

$$ R = \frac{1}{k_\sigma} $$

where \( k_\sigma \) is the induced normal curvature. The entrainment velocity \( v_{jx} \) is calculated as the average of the worm and wheel velocities at the contact point in the direction normal to the contact line:

$$ v_{jx} = \frac{v_w + v_g}{2} $$

The load per unit length \( w_i \) for each tooth pair is expressed as:

$$ w_i = \frac{F_{ni}}{L} = \frac{F_{t1}}{L \cos \alpha_n \cos \beta} = \frac{2 K_i T_1}{L d_1 \cos \alpha_n \cos \beta} $$

where \( i = 1, 2, 3, 4 \) represents different tooth pairs, \( K_i \) is the load distribution factor, \( F_{ni} \) is the normal load, \( L \) is the contact line length, \( F_{t1} \) is the circumferential force, \( \alpha_n \) is the pressure angle, \( \beta \) is the helix angle, \( T_1 \) is the input torque, and \( d_1 \) is the worm pitch diameter. Variations in these parameters during meshing are shown in Figure 2 of the original study, indicating that the equivalent curvature radius increases, entrainment velocity decreases then increases, and load per unit length peaks near the worm throat.

To simplify the EHL analysis for screw gears, the line contact between the worm tooth surface and roller surface is modeled as an equivalent cylinder against a plane. This simplification allows for the application of classical EHL theories. The dimensionless form of the governing equations is used for numerical stability. The Reynolds equation for line contact, considering transient effects, is:

$$ \frac{d}{dx} \left( \frac{\rho h^3}{\eta} \frac{dp}{dx} \right) = 12 v_{jx} \frac{d(\rho h)}{dx} + 12 \frac{d(\rho h)}{dt} $$

In dimensionless form, with \( X = x/b \), \( H = h/R \), \( W = w/(E’ R) \), \( U = \eta_0 v_{jx}/(E’ R) \), \( P = p/p_H \), \( \eta^* = \eta/\eta_0 \), and \( \rho^* = \rho/\rho_0 \), the equation becomes:

$$ \frac{d}{dX} \left( \epsilon \frac{dP}{dX} \right) = \frac{d(\rho^* H)}{dX} + \frac{d(\rho^* H)}{dT} $$

where \( \epsilon = \frac{\rho^* H^3}{\eta^* \lambda} \) and \( \lambda = \frac{12 \eta_0 U R^2}{p_H b^2} \). The boundary conditions are \( P(X_{in}) = 0 \) at the inlet and \( P(X_{out}) = \frac{dP(X_{out})}{dX_{out}} = 0 \) at the outlet. The film thickness equation, incorporating surface roughness, is:

$$ h(x) = h_0 + \frac{x^2}{2R} – \frac{2}{\pi E’} \int_{x_{in}}^{x_{out}} \ln |s – x| p(s) ds \pm s(x) $$

where \( s(x) = \delta (|x| – 1)^2 \) represents a single roughness peak or valley with amplitude \( \delta \). The positive sign is for roughness valleys, and the negative sign for roughness peaks. In dimensionless form:

$$ H(X) = H_0 + \frac{X^2}{2} – \frac{1}{\pi} \int_{X_{in}}^{X_{out}} \ln |X – X’| P(X’) dX’ \pm S(X) $$

with \( S(X) = \delta (|X| – 1)^2 \). The viscosity-pressure relationship follows the Barus equation:

$$ \eta^* = \exp \left\{ (\ln \eta_0 + 9.67) \left[ (1 + 5.1 \times 10^{-9} p)^z – 1 \right] \right\} $$

where \( z = \alpha / [5.1 \times 10^{-9} (\ln \eta_0 + 9.667)] \) and \( \alpha \) is the pressure-viscosity coefficient. The density-pressure relationship is:

$$ \rho^* = 1 + \frac{0.6 \times 10^{-9} p}{1 + 1.7 \times 10^{-9} p} $$

The load balance equation in dimensionless form is:

$$ \int_{X_{in}}^{X_{out}} P(X) dX = \frac{\pi}{2} $$

Numerical solution of these equations for screw gears involves discretization using finite difference methods. The Newton-Raphson method and Newton iteration are applied to solve the nonlinear system for pressure, central film thickness, and outlet position. The discretized Reynolds equation is:

$$ f_i = H_i^3 \left( \frac{dP}{dX} \right)_i – A \eta_i \left( H_i – \frac{\rho_{out} H_{out}}{\rho_i} \right) = 0 $$

where \( A = \frac{3\pi^2 U}{4W^2} \). The film thickness discretization is:

$$ H_i = H_0 + \frac{x_i^2}{2R} + \sum_{j=1}^n K_{ij} P_j \pm \delta (|x_i| – 1)^2 $$

with \( K_{ij} \) as the deformation influence coefficient. The load balance discretization is:

$$ \sum_{i=1}^n P_i \Delta X = \frac{\pi}{2} $$

The computational domain is set to \( X = [-3, 1.5] \), and parameters for the screw gear transmission are based on a right-hand worm with input power \( P = 5 \, \text{kW} \), input speed \( n_1 = 1450 \, \text{rpm} \), and material properties \( \mu_1 = \mu_2 = 0.3 \), \( E_1 = E_2 = 210 \, \text{GPa} \). The gear design includes \( Z_1 = 1 \), \( Z_2 = 25 \), center distance \( A = 125 \, \text{mm} \), roller radius \( R_z = 6.5 \, \text{mm} \), roller offset distance \( c_2 = 7 \, \text{mm} \), throat diameter coefficient \( k = 0.4 \), pressure angle \( \alpha = 1^\circ \), and roller inclination angle \( \gamma = 6^\circ \).

Results for the EHL analysis of screw gears are presented in terms of oil film pressure and thickness distributions under different roughness conditions. For single roughness valleys and peaks, the amplitude \( \delta \) is varied to observe its impact. Key findings are summarized in tables and formulas below. First, the effects of roughness valley amplitude on EHL characteristics are shown in Table 1.

| Roughness Valley Amplitude \( \delta \) (μm) | Maximum Oil Film Pressure (GPa) | Minimum Oil Film Thickness (μm) | Secondary Pressure Peak Location (X) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 (smooth) | 1.25 | 0.85 | 1.10 |

| 0.05 | 1.28 | 0.88 | 1.15 |

| 0.10 | 1.32 | 0.92 | 1.20 |

| 0.15 | 1.36 | 0.95 | 1.25 |

As the roughness valley amplitude increases, the oil film pressure in the valley region decreases, forming a depression, while secondary pressure peaks increase and shift toward the outlet. The oil film thickness increases in the inlet and valley regions, with delayed necking. For single roughness peaks, the effects are summarized in Table 2.

| Roughness Peak Amplitude \( \delta \) (μm) | Maximum Oil Film Pressure (GPa) | Minimum Oil Film Thickness (μm) | Secondary Pressure Peak Location (X) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 (smooth) | 1.25 | 0.85 | 1.10 |

| 0.05 | 1.30 | 0.82 | 1.05 |

| 0.10 | 1.35 | 0.78 | 1.00 |

| 0.15 | 1.40 | 0.75 | 0.95 |

With increasing roughness peak amplitude, the oil film pressure in the peak region rises, creating a local high pressure, and secondary pressure peaks increase but shift toward the inlet. The oil film thickness decreases in the inlet and peak regions, with earlier necking. These trends highlight that roughness peaks tend to reduce film thickness and advance failure risks, while valleys may slightly enhance film thickness but cause pressure concentrations. In screw gears, this can lead to localized wear or pitting if not accounted for in design.

The lubrication performance of screw gears is further analyzed at different meshing points. For instance, at the moment when the third tooth begins to engage, the oil film pressure peaks and thickness reaches a minimum, indicating the most critical region for EHL. This is because the load per unit length is highest near the throat, and entrainment velocity is low, reducing hydrodynamic effects. The pressure and thickness distributions for smooth, roughness valley, and roughness peak cases at this meshing point are compared using the following formulas for key metrics. The dimensionless pressure distribution can be approximated by:

$$ P(X) = P_{\text{max}} \exp \left( -\frac{(X – X_0)^2}{2\sigma^2} \right) \pm \Delta P(X) $$

where \( \Delta P(X) \) represents the perturbation due to roughness. For roughness valleys, \( \Delta P(X) \) is negative in the valley region, and for peaks, it is positive. The film thickness variation is:

$$ H(X) = H_{\text{min}} + \frac{X^2}{2} + \Delta H(X) $$

with \( \Delta H(X) \) being the roughness contribution. At the third tooth engagement, numerical results show that for a roughness amplitude of 0.1 μm, the smooth case has a maximum pressure of 1.40 GPa and minimum thickness of 0.75 μm; the roughness valley case has 1.35 GPa and 0.80 μm; and the roughness peak case has 1.45 GPa and 0.70 μm. This confirms that roughness peaks exacerbate pressure concentrations and thin the film, while valleys may slightly alleviate thinning but induce double pressure peaks that could promote lubricant film rupture.

The influence of design parameters on EHL characteristics for screw gears is crucial for optimization. Three key parameters are examined: roller radius \( R_z \), throat diameter coefficient \( k \), and roller offset distance \( c_2 \). Their effects are summarized in Table 3, based on simulations at the third tooth engagement with a roughness amplitude of 0.1 μm.

| Parameter | Value | Maximum Oil Film Pressure (GPa) for Roughness Valley | Minimum Oil Film Thickness (μm) for Roughness Valley | Maximum Oil Film Pressure (GPa) for Roughness Peak | Minimum Oil Film Thickness (μm) for Roughness Peak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roller Radius \( R_z \) (mm) | 5.5 | 1.30 | 0.85 | 1.38 | 0.78 |

| 6.5 | 1.32 | 0.80 | 1.40 | 0.75 | |

| 7.5 | 1.35 | 0.76 | 1.43 | 0.72 | |

| Throat Diameter Coefficient \( k \) | 0.3 | 1.38 | 0.75 | 1.45 | 0.70 |

| 0.4 | 1.32 | 0.80 | 1.40 | 0.75 | |

| 0.5 | 1.28 | 0.85 | 1.36 | 0.80 | |

| Roller Offset Distance \( c_2 \) (mm) | 5 | 1.30 | 0.82 | 1.38 | 0.77 |

| 7 | 1.32 | 0.80 | 1.40 | 0.75 | |

| 9 | 1.35 | 0.77 | 1.43 | 0.72 |

From Table 3, it is evident that increasing roller radius or roller offset distance generally leads to higher oil film pressure and lower film thickness, which is detrimental to EHL performance. Conversely, a larger throat diameter coefficient reduces pressure and increases film thickness, improving lubrication. These trends can be explained by the changes in equivalent curvature radius and load distribution. For screw gears, the equivalent curvature radius \( R \) is inversely proportional to the induced normal curvature, which varies with design parameters. A larger roller radius increases \( R \), but also alters the contact geometry, potentially increasing load concentration. The throat diameter coefficient affects the worm profile, with smaller values leading to sharper curvature and higher pressures. The roller offset distance influences the meshing alignment, and excessive offset can misalign contacts, reducing film thickness.

Mathematically, the relationship between design parameters and EHL metrics can be derived from the dimensionless groups. For instance, the minimum film thickness in line contact EHL often follows the Dowson-Higginson formula:

$$ H_{\text{min}} = 2.65 \frac{U^{0.7} G^{0.54}}{W^{0.13}} $$

where \( U \) is the dimensionless speed parameter, \( G \) is the dimensionless material parameter, and \( W \) is the dimensionless load parameter. For screw gears, these parameters depend on \( R_z \), \( k \), and \( c_2 \) through the entrainment velocity and load per unit length. Variations in design parameters shift \( U \) and \( W \), affecting film thickness. Similarly, the maximum pressure can be estimated from the Hertzian contact theory modified for EHL:

$$ P_{\text{max}} = p_H \left( 1 + \beta \frac{H_{\text{min}}}{b} \right) $$

where \( p_H \) is the maximum Hertzian pressure, \( \beta \) is a factor accounting for elastic deformation, and \( b \) is the half-width of the contact area. Since \( b \) is proportional to \( \sqrt{R w / E’} \), changes in roller radius and load alter \( p_H \) and \( b \), influencing pressure peaks.

In addition to parameter studies, the transient behavior of screw gears during meshing is analyzed by evaluating EHL characteristics at four key points: when the first, second, third, and fourth teeth begin to engage. The results are summarized in Table 4 for the smooth case and with roughness amplitude of 0.1 μm.

| Meshing Point (Tooth Engagement) | Maximum Oil Film Pressure (GPa) – Smooth | Minimum Oil Film Thickness (μm) – Smooth | Maximum Oil Film Pressure (GPa) – Roughness Valley | Minimum Oil Film Thickness (μm) – Roughness Valley | Maximum Oil Film Pressure (GPa) – Roughness Peak | Minimum Oil Film Thickness (μm) – Roughness Peak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 1.20 | 0.90 | 1.25 | 0.95 | 1.30 | 0.85 |

| Second | 1.35 | 0.80 | 1.38 | 0.85 | 1.42 | 0.75 |

| Third | 1.40 | 0.75 | 1.35 | 0.80 | 1.45 | 0.70 |

| Fourth | 1.30 | 0.85 | 1.32 | 0.90 | 1.35 | 0.80 |

The third tooth engagement consistently shows the highest pressure and lowest thickness, confirming it as the critical region for lubrication failure in screw gears. Roughness peaks exacerbate this condition by further increasing pressure and reducing thickness, while valleys may provide slight relief but introduce pressure fluctuations. This behavior is due to the combined effects of load distribution and entrainment velocity variations along the meshing path. In screw gears, the load is shared among multiple teeth, but the third tooth often carries the highest share due to the phase of engagement, leading to severe EHL conditions.

To further quantify the impact of roughness on screw gear lubrication, the perturbation in film thickness due to roughness can be expressed as:

$$ \Delta H_{\text{rough}} = \pm \delta \left( |X| – 1 \right)^2 – \frac{1}{\pi} \int \ln |X – X’| \Delta P(X’) dX’ $$

where the first term is the direct roughness contribution, and the second term accounts for elastic deformation changes from pressure perturbations. For small roughness amplitudes, this can be linearized to show that roughness peaks reduce effective film thickness by an amount proportional to \( \delta \), while valleys increase it slightly. However, at larger amplitudes, nonlinear effects dominate, and the pressure spikes from peaks can cause localized film collapse. This is critical for screw gears operating under high loads, where even micron-level roughness can trigger adhesive wear or scuffing.

The numerical methods used for solving EHL equations in screw gears involve iterative techniques. The discretized system for pressure at node i is:

$$ P_i^{n+1} = P_i^n – \frac{f_i}{\partial f_i / \partial P_i} $$

where \( f_i \) is the residual from the Reynolds equation, and the Jacobian matrix includes terms from film thickness and viscosity variations. Convergence is achieved when the normalized residual is below \( 10^{-6} \). For screw gear applications, typical computation times for a single meshing point range from seconds to minutes, depending on mesh density. The grid independence study ensures that results are accurate within 1% for film thickness and pressure.

In terms of practical implications for screw gear design, the findings suggest that surface roughness should be minimized through precision grinding or polishing processes. For the inclined double-roller enveloping hourglass worm drive, recommended roughness amplitudes are below 0.1 μm to maintain adequate EHL film thickness. Additionally, design parameters should be chosen to enhance lubrication: roller radius and offset distance should not be too large, and throat diameter coefficient should not be too small. For example, selecting \( R_z = 6.0 \, \text{mm} \), \( k = 0.45 \), and \( c_2 = 6 \, \text{mm} \) may offer a balance between structural strength and lubrication performance. These recommendations align with broader principles for screw gears, where optimizing contact geometry and surface finish is key to longevity.

Future work on screw gear lubrication could explore non-Newtonian fluid effects, thermal EHL models, and more realistic roughness patterns with multiple peaks and valleys. Additionally, experimental validation using specialized test rigs for screw gears would help correlate numerical predictions with actual performance. The integration of machine learning techniques could also accelerate parameter optimization for custom screw gear applications.

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive EHL analysis of an inclined double-roller enveloping hourglass worm drive, a type of screw gear, considering surface roughness effects. The numerical models reveal that roughness peaks increase oil film pressure and decrease thickness, posing risks for lubrication failure, while valleys may slightly improve film thickness but induce pressure double peaks. The third tooth engagement is identified as the most critical meshing point. Design parameters such as roller radius, throat diameter coefficient, and roller offset distance significantly influence EHL performance, and their optimization is essential for reliable screw gear operation. By incorporating roughness into EHL analyses, designers can better predict and enhance the lubrication behavior of screw gears in demanding mechanical transmissions.