In the field of mechanical power transmission, achieving high reduction ratios with compact design, smooth operation, and high load capacity is a persistent engineering challenge. Among the solutions, screw gears, particularly worm drives, have been prominent. A significant evolution within this category is the spiroid or cone worm gear set, first developed in the mid-20th century. These screw gears offer advantages such as large transmission ratios, multi-tooth contact, and the ability to use hardened steel for the worm wheel. Building upon this foundation, a novel design known as the dual-lead, line-contact, offset worm drive was introduced. This design simplified the theoretical foundation and offered more straightforward manufacturing principles while retaining all the benefits of traditional cone worm screw gears. However, a key limitation remained: the requirement for specialized cutting tools to generate the precise conjugate tooth surfaces for both the worm and the wheel. This necessity increases cost and complexity, especially for small-batch or single-unit production.

To address this manufacturing challenge, an engineering approximation method is proposed, leading to the concept of the Quasi Dual-Lead Worm Drive. This method aims to retain the favorable kinematic and load-bearing characteristics of the ideal dual-lead offset worm drive while utilizing standard, readily available cutting tools. The core of this approximation lies in substituting the theoretically perfect tooth surfaces of the worm with surfaces that are easier to machine. This paper conducts a detailed analysis of the inherent errors introduced by this engineering approximation, establishes the mathematical framework for quantifying these errors, and validates the practical feasibility of the approach through design and testing.

Principles of Quasi Dual-Lead Worm Gearing

In the ideal dual-lead, line-contact, offset worm drive, the worm tooth flanks are two distinct involute helicoids. These surfaces are generated by a straight cutting edge lying in the tangent plane of a base cylinder. Each flank has its own base cylinder radius and base helix angle, requiring separate and precise machining operations. The mating worm wheel must then be cut using a dedicated hob that is conjugate to this specific worm geometry.

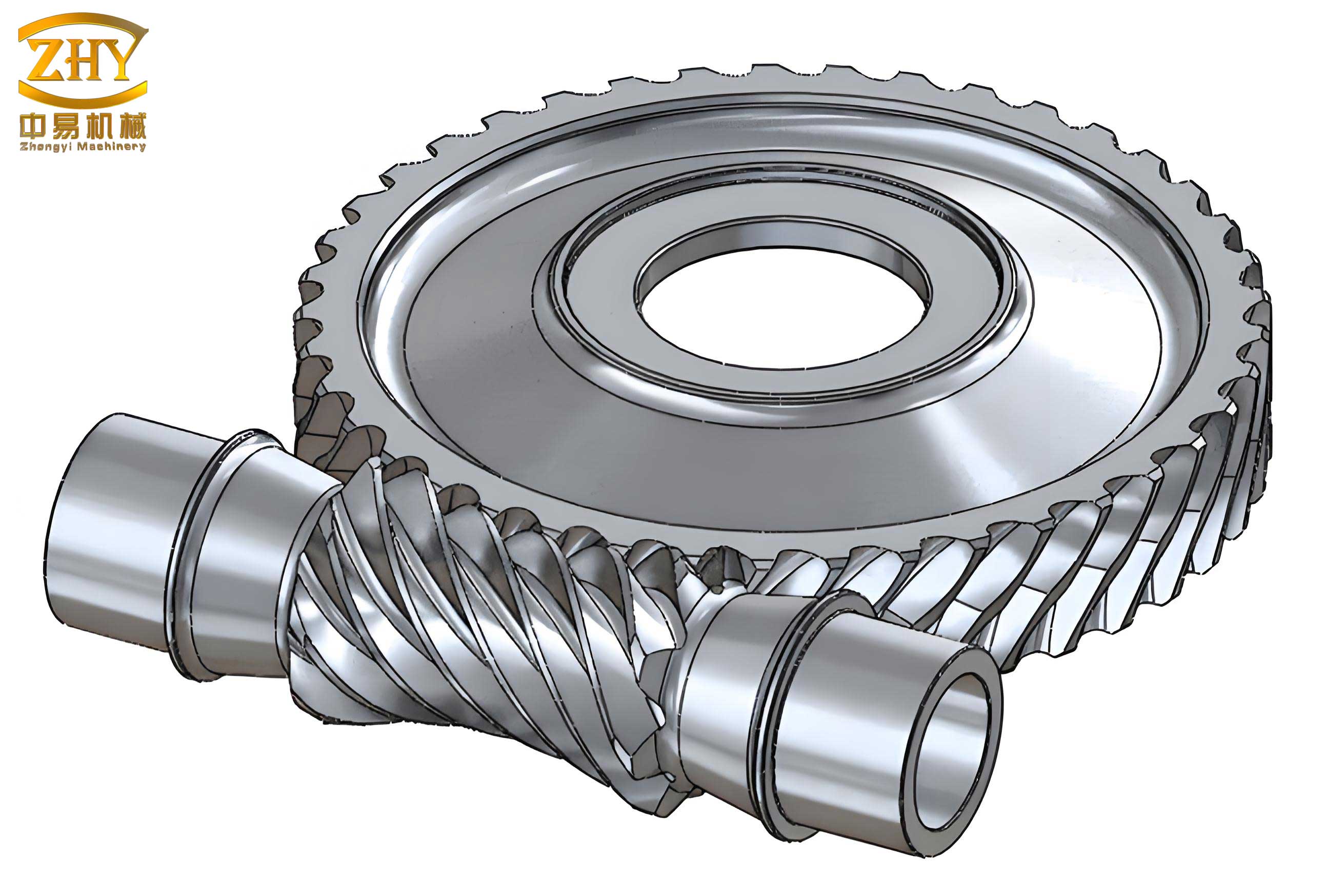

The quasi dual-lead method introduces a pragmatic simplification. It approximates each of the worm’s involute helicoid flanks with an Archimedean spiral surface. An Archimedean worm, or straight-sided axial profile worm, can be readily generated on a standard lathe using a tool with a straight cutting edge set at the appropriate pressure angle. This is a significant manufacturing advantage. Consequently, following the theory of gearing (the law of conjugate tooth surfaces), the worm wheel can now be produced using a standard modular gear hob on a conventional gear hobbing machine. The pair manufactured under this principle constitutes the quasi dual-lead worm drive. It is designed to emulate the performance of the ideal dual-lead offset worm drive but with vastly simplified production processes. A representative pair of these screw gears is shown below.

The fundamental difference between the two designs is summarized in the following table:

| Aspect | Ideal Dual-Lead Offset Worm Drive | Quasi Dual-Lead Worm Drive |

|---|---|---|

| Worm Tooth Surface | Two distinct involute helicoids. | Two distinct Archimedean spiral surfaces. |

| Worm Manufacturing | Requires specialized setup with a straight-edge tool in the base tangent plane for each flank. | Can be turned on a lathe using a standard tool, similar to an Acme thread. |

| Wheel Manufacturing | Requires a dedicated hob conjugate to the specific worm. | Can be hobbed using a standard modular gear hob. |

| Theoretical Contact | Line contact. | Point contact (approximating line contact after run-in). |

| Primary Advantage | Theoretical optimality for load distribution. | Manufacturing simplicity and cost-effectiveness for low volumes. |

Engineering Approximation and Sources of Error

The substitution of an Archimedean surface for an involute helicoid inevitably introduces tooth flank deviations, which are the source of transmission error in these screw gears. To analyze this, consider the geometry of the worm. Let the two theoretical involute helicoid flanks of the ideal worm be defined by their base cylinders with radii \( r_{b1} \) and \( r_{b2} \), and their base helix angles \( \beta_{b1} \) and \( \beta’_{b1} \). Their generating lines lie in tangent planes \( Q \) and \( Q’ \), respectively.

In the quasi dual-lead worm, we approximate these with two Archimedean spiral surfaces, \( \Sigma_1 \) and \( \Sigma_2 \). These surfaces are generated by a straight line that intersects the worm axis and makes a specific lead angle. Their equations in a coordinate system \( O(x, y, z) \) attached to the worm, where \( z \) is the worm axis, can be expressed as follows.

For the first flank (\( \Sigma_1 \)), approximating the involute helicoid with base cylinder \( r_{b2} \):

$$ x = t \cos\tilde{\beta}_{b1} \cos\eta $$

$$ y = t \cos\tilde{\beta}_{b1} \sin\eta $$

$$ z = t \sin\tilde{\beta}_{b1} + \frac{P}{2\pi}\eta $$

where \( t \) and \( \eta \) are parameters, \( \tilde{\beta}_{b1} \) is the chosen lead angle for the approximation, and \( P \) is the axial lead.

For the second flank (\( \Sigma_2 \)):

$$ x = t_1 \cos\tilde{\beta}’_{b1} \cos\eta_1 $$

$$ y = t_1 \cos\tilde{\beta}’_{b1} \sin\eta_1 $$

$$ z = t_1 \sin\tilde{\beta}’_{b1} + \frac{P’}{2\pi}\eta_1 $$

The core task of the approximation is to select parameters \( \tilde{\beta}_{b1} \), \( \tilde{\beta}’_{b1} \), \( P \), and \( P’ \) such that the Archimedean surfaces closely match the theoretical involute helicoids within the active working zone of the tooth.

The error analysis focuses on the intersection curve of the approximated surface with the crucial tangent plane \( Q \). Consider surface \( \Sigma_1 \). Its intersection with plane \( Q \) (where, for simplicity in a specific coordinate alignment, we consider a plane related to the base cylinder \( r_{b2} \)) yields a space curve \( \Gamma_1 \). The equation of \( \Gamma_1 \) is derived by relating the surface parameters to the condition defining plane \( Q \). For a given geometric setup, it can be expressed in a planar coordinate system within \( Q \) as:

$$ z = r_{b2} \cdot \tan\beta_{b1} \cdot \arctan\left(\frac{r_{b2}}{x}\right) + \frac{\tan\tilde{\beta}_{b1}}{\sin\left(\arctan\left(\frac{r_{b2}}{x}\right)\right)} \cdot r_{b2} $$

where \( x \in (q \cdot r_{b2}, n \cdot r_{b2}) \) defines the active zone on the flank, with \( q \) and \( n \) being dimensionless boundary parameters from the worm design.

In the ideal worm, the intersection of the involute helicoid with plane \( Q \) is a straight line \( L_{ideal} \). In the quasi worm, the intersection is the curve \( \Gamma_1 \). The approximation error is therefore quantified by how well a straight line \( L_{approx} \) can be fitted to curve \( \Gamma_1 \) over the active interval. The quality of the fit is assessed using two error metrics: the slope error and the normal distance error.

Error Calculation and Formulation

This section details the mathematical procedure for calculating the two primary error metrics for one flank (the “outer engagement” side). The process is identical for the other flank (“inner engagement”).

Step 1: Fitting a Straight Line to the Intersection Curve.

Within the working interval \( x \in [x_1, x_2] \), where \( x_1 = q \cdot r_{b2} \) and \( x_2 = n \cdot r_{b2} \), we select two points on the curve \( \Gamma_1 \). Their coordinates are:

$$ (x_1, z_1) = \left( q r_{b2},\ \frac{r_{b2}}{\sin(\arctan(1/q))} \tan\tilde{\beta}_{b1} + r_{b2} \tan\beta_{b1} \arctan(1/q) \right) $$

$$ (x_2, z_2) = \left( n r_{b2},\ \frac{r_{b2}}{\sin(\arctan(1/n))} \tan\tilde{\beta}_{b1} + r_{b2} \tan\beta_{b1} \arctan(1/n) \right) $$

The secant line \( L_{approx} \) passing through these points has a slope \( \tan\bar{\beta}_{b1} \) given by:

$$ \tan\bar{\beta}_{b1} = \frac{z_1 – z_2}{x_1 – x_2} $$

However, the initial secant based on the interval endpoints may not be the best fit. An iterative calculation is performed, adjusting the points \( (x_1, z_1) \) and \( (x_2, z_2) \) along \( \Gamma_1 \), to find the straight line \( L_2 \) that minimizes the maximum normal deviation from the curve. The slope of this optimal line is denoted \( \tan\hat{\beta}_{b1} \).

Step 2: Defining and Calculating Error Metrics.

1. Slope Error (\( \Delta k \)): This measures the difference between the slope of the fitted line and the theoretical slope.

$$ \Delta k = | \tan\hat{\beta}_{b1} – \tan\beta_{b1} | $$

2. Normal Distance Error (\( \Delta \)): This measures half of the maximum normal distance between the fitted straight line \( L_2 \) and the actual curve \( \Gamma_1 \) over the entire active interval. If the line equation is \( Z = mX + c \) in the plane’s coordinates, and the curve gives \( z(x) \), the normal distance at a point \( x \) is proportional to \( |z(x) – (m x + c)| \). The error is defined as:

$$ \Delta = \frac{1}{2} \max_{x \in [q r_{b2}, n r_{b2}]} \left| \left( z(x) – (m x + c) \right) \cdot \cos\hat{\beta}_{b1} \right| $$

The factor \( \cos\hat{\beta}_{b1} \) projects the vertical deviation onto the direction normal to the line.

Similarly, for the other worm flank, we calculate the inner engagement slope error \( \Delta k’ \) and distance error \( \Delta’ \). The approximation is considered acceptable for engineering purposes when \( \Delta \) and \( \Delta’ \) are sufficiently small (on the order of micrometers) and \( \Delta k \) and \( \Delta k’ \) are very small (typically less than \( 10^{-2} \)). This indicates that the Archimedean surfaces will closely mimic the kinematic behavior of the ideal involute helicoid surfaces in the context of screw gears.

The following table summarizes the key parameters and variables involved in the error calculation for a quasi dual-lead worm screw gear.

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| \( r_{b1}, r_{b2} \) | Base cylinder radii of the ideal worm’s involute helicoids. |

| \( \beta_{b1}, \beta’_{b1} \) | Base helix angles of the ideal worm’s involute helicoids. |

| \( \tilde{\beta}_{b1}, \tilde{\beta}’_{b1} \) | Lead angles chosen for the approximating Archimedean surfaces. |

| \( \hat{\beta}_{b1}, \hat{\beta}’_{b1} \) | Slopes of the optimal straight-line fits to the intersection curves. |

| \( q, n \) | Dimensionless factors defining the active zone boundaries on the worm tooth. |

| \( \Delta k, \Delta k’ \) | Slope error for outer and inner engagement flanks. |

| \( \Delta, \Delta’ \) | Normal distance (form) error for outer and inner engagement flanks. |

Manufacturing of the Worm Wheel and Associated Considerations

A critical advantage of the quasi dual-lead method is the use of a standard gear hob to generate the worm wheel. For a pair with a right-handed quasi worm and a left-handed worm wheel, the setup is as follows. A standard left-handed modular gear hob is used. Its outer diameter \( D \) is made equal to the major diameter of the quasi worm at its larger end \( d_d \). The hob axis is offset by the same center distance \( E \) used in the final assembly of the screw gears.

Furthermore, the hob axis is tilted by an angle \( \theta \) relative to the plane perpendicular to the worm wheel axis. This tilt angle \( \theta \) is precisely equal to the cone angle of the quasi worm. This geometric relationship ensures that the generating surface of the hob closely corresponds to the Archimedean surface of the worm. According to the setup geometry, the effective pressure angle \( \alpha \) of the hob, the tilt angle \( \theta \), and the worm’s base helix angle are related by \( \beta_{b1} = \alpha – \theta \).

It is paramount to note that, unlike conventional worm wheel hobbing, the hob approaches the workpiece from its face rather than its side. Since the wheel is generated using the conjugate principle based on the approximated worm geometry (the hob acts as the mating worm), there is no theoretical error introduced in the wheel generation process itself. The wheel tooth form is the exact conjugate of the Archimedean worm surface. Therefore, all transmission errors in the quasi dual-lead screw gear pair originate solely from the approximation of the worm tooth flanks, not from the wheel manufacturing process.

Design, Manufacturing, and Experimental Validation

To validate the quasi dual-lead theory, two distinct screw gear pairs were designed, manufactured, and tested. The primary parameters were selected to cover different ratios:

- Pair A: Worm wheel tooth number \( z_2 = 70 \), single-start worm (\( z_1 = 1 \)), resulting in a ratio of 70:1.

- Pair B: Worm wheel tooth number \( z_2 = 410 \), single-start worm (\( z_1 = 1 \)), resulting in a ratio of 410:1.

Both the worm and the wheel were manufactured from steel. The worms were turned on a lathe to produce the dual-lead Archimedean surfaces. The wheels were hobbed on a standard gear hobbing machine using a modular gear hob, with the axis set at the calculated offset \( E \) and tilt angle \( \theta \). For both designs, the calculated approximation errors \( \Delta, \Delta’, \Delta k, \Delta k’ \) were verified to be less than the acceptable threshold of \( 10^{-2} \) for the slope errors, confirming the validity of the approximation.

A crucial post-processing step was employed to minimize the impact of residual errors and improve surface finish: running-in or lapping. The worm and wheel pair were run together under light load with a fine abrasive compound. This wear-in process allows the mating surfaces to locally conform to each other, transforming the initial point contact (resulting from form errors) into a polished area contact that closely approximates the desired line contact. This significantly reduces transmission error, noise, and improves load distribution in these screw gears.

The table below summarizes the key outcomes for the two experimental screw gear pairs:

| Parameter / Outcome | Pair A (70:1) | Pair B (410:1) |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission Ratio | 70 | 410 |

| Calculated Slope Error \( \Delta k \) | < \( 10^{-2} \) | < \( 10^{-2} \) |

| Calculated Form Error \( \Delta \)** | Acceptably small | Acceptably small |

| Worm Machining | Lathe turning (standard) | Lathe turning (standard) |

| Wheel Machining | Gear hobbing (standard hob) | Gear hobbing (standard hob) |

| Post-Processing | Lapping/Running-in | Lapping/Running-in |

| Test Result | Smooth operation, low noise, high positional accuracy. | Smooth operation, very high reduction ratio achieved stably. |

** Note: The specific numerical value of \( \Delta \) is design-dependent and typically in the micron range after optimization.

The transmission tests confirmed that both pairs operated smoothly, transmitted motion accurately, and exhibited the characteristic compactness and high reduction ratio of cone worm screw gears. No signs of premature wear or binding were observed after the running-in period.

Conclusion

The analysis and experimental work presented demonstrate that the Quasi Dual-Lead Worm Drive is a viable and practical engineering solution. The key conclusions are:

- Functional Principle: The method successfully approximates the ideal dual-lead offset worm geometry by substituting Archimedean spiral surfaces for involute helicoids on the worm. The worm wheel is then correctly generated as the conjugate surface using standard tools. This approach preserves the fundamental kinematics and major advantages of high-ratio cone worm screw gears.

- Controlled Errors: The inherent tooth flank deviation (error) due to the approximation is quantifiable using the defined slope error (\( \Delta k \)) and normal distance error (\( \Delta \)) metrics. These errors can be minimized through careful design parameter selection (optimizing \( \tilde{\beta}_{b1}, q, n \)) and are typically small enough not to impair basic functionality.

- Manufacturing Simplicity: The most significant benefit is the dramatic simplification of manufacturing. Worms can be produced on standard lathes, and worm wheels can be cut using commercially available modular gear hobs on conventional hobbing machines. This eliminates the need for expensive, custom-made cutting tools, making the technology highly accessible for prototyping and small-batch production of screw gears.

- Performance Enhancement via Run-in: The initial point contact condition, a consequence of the form errors, is effectively mitigated through a controlled running-in (lapping) process. This allows the mating surfaces to self-conform, improving contact pattern, reducing transmission error, and increasing load capacity, effectively yielding a performance that closely approximates the ideal line contact state.

- Experimental Validation: The successful design, manufacture, and testing of screw gear pairs with ratios of 70 and 410 provide concrete evidence of the correctness and practical effectiveness of the quasi dual-lead approach. The screw gears operated smoothly and reliably, fulfilling the expectations for such high-ratio drives.

In summary, the quasi dual-lead worm gearing method offers a powerful trade-off: it accepts small, manageable, and compensatable geometric errors in exchange for drastically reduced manufacturing complexity and cost. This makes advanced cone worm screw gear performance attainable in contexts where specialized tooling is impractical, thereby expanding the potential applications for this efficient and compact form of power transmission.