In the realm of mechanical transmission systems, screw gears play a pivotal role due to their ability to provide high reduction ratios and compact design. However, traditional screw gears often suffer from issues such as high sliding friction, significant wear, and thermal problems, which limit their efficiency and lifespan. As a researcher focused on advancing gear technology, I have been exploring novel designs that mitigate these drawbacks. In this article, I present a comprehensive analysis of a new type of screw gear transmission: the roller enveloping end face meshing screw gear. This design combines the advantages of roller enveloping principles and end face engagement to enhance performance. Throughout this discussion, I will emphasize the significance of screw gears in modern engineering and how this innovation addresses common challenges. The analysis covers the working principle, mathematical modeling, meshing theory, and key characteristics, supported by formulas, tables, and visual aids. By delving into the details, I aim to provide a thorough understanding of this advanced screw gear system, which promises reduced friction, improved efficiency, and longer service life.

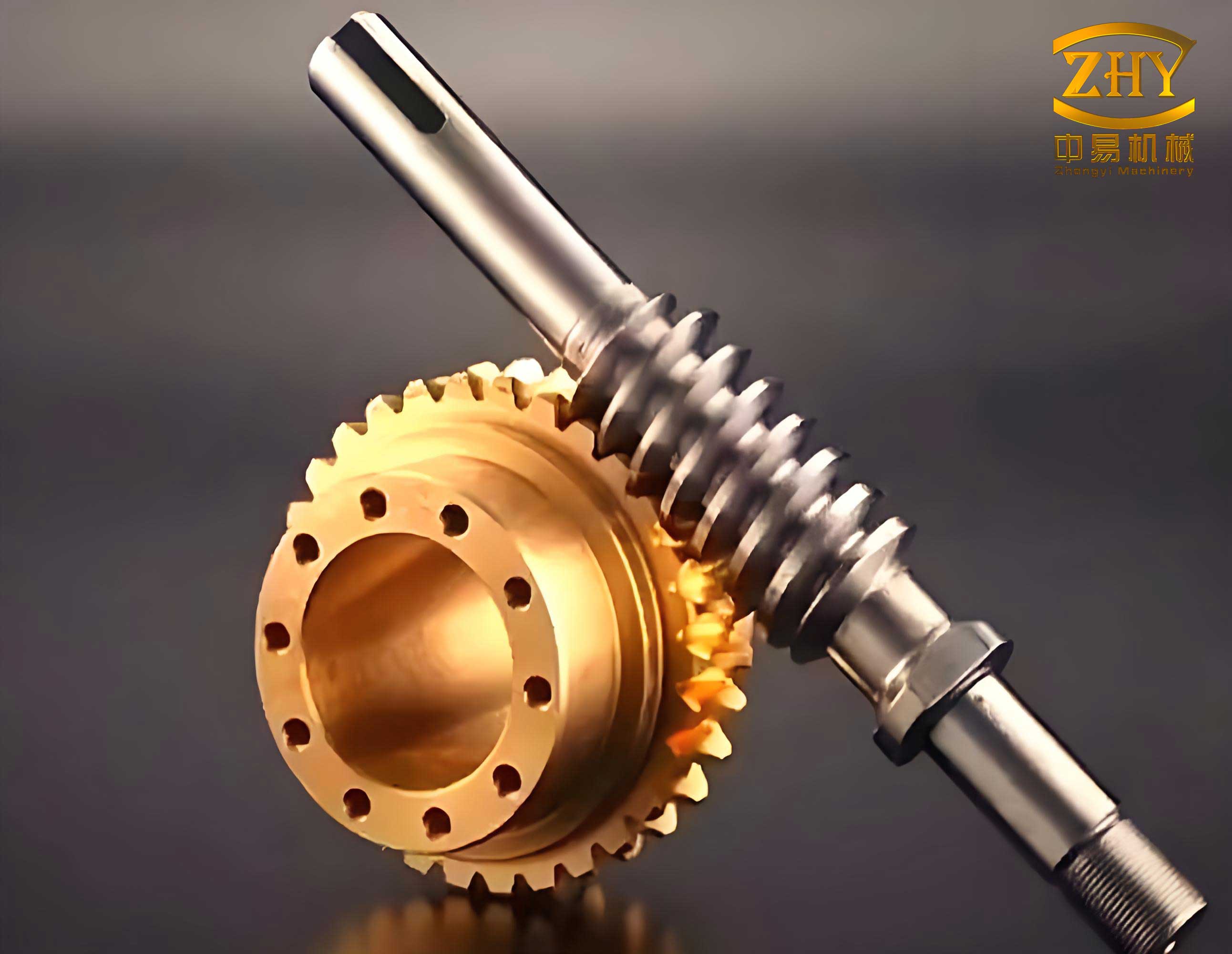

The roller enveloping end face meshing screw gear operates on a unique principle that distinguishes it from conventional screw gears. In this configuration, the worm gear consists of two segments mounted on a common shaft, positioned symmetrically on the left and right sides. The worm wheel features rollers as its teeth, which can rotate about their own axes, effectively converting sliding friction into rolling friction. This is a key improvement in screw gears, as it reduces wear and heat generation. The end face engagement ensures that multiple tooth pairs are in contact simultaneously, increasing load capacity and eliminating backlash. When the worm shaft rotates as the input, the worm wheel outputs motion, with the left worm segment engaging the upper teeth of the worm wheel and the right segment engaging the lower teeth. This symmetric meshing allows for seamless operation in both forward and reverse directions, making it ideal for precision applications. The use of rollers, such as needle bearings, further enhances durability by minimizing friction at the contact points. This design represents a significant step forward in screw gear technology, offering a solution to the long-standing problems of efficiency and reliability.

To analyze the meshing behavior of this screw gear system, a precise mathematical model is essential. I establish several coordinate systems to describe the geometry and motion. Let $\sigma_1(\mathbf{i}_1, \mathbf{j}_1, \mathbf{k}_1)$ be the fixed coordinate system of the worm, $\sigma_2(\mathbf{i}_2, \mathbf{j}_2, \mathbf{k}_2)$ the fixed coordinate system of the worm wheel, $\sigma_1′(\mathbf{i}_1′, \mathbf{j}_1′, \mathbf{k}_1′)$ the moving coordinate system attached to the worm, and $\sigma_2′(\mathbf{i}_2′, \mathbf{j}_2′, \mathbf{k}_2′)$ the moving coordinate system attached to the worm wheel. The worm rotates about $\mathbf{k}_1 = \mathbf{k}_1’$ with angular velocity $\omega_1$, and the worm wheel rotates about $\mathbf{k}_2 = \mathbf{k}_2’$ with angular velocity $\omega_2$. The center distance is denoted by $A$. The roller surface, which forms the teeth of the worm wheel, is described in a local coordinate system $\sigma_0(\mathbf{i}_0, \mathbf{j}_0, \mathbf{k}_0)$ attached to the roller. The position of $O_0$ in $\sigma_2$ is given by $(a_2, b_2, c_2)$. At the contact point $O_p$, an active frame $\sigma_p(\mathbf{e}_1, \mathbf{e}_2, \mathbf{n})$ is set up, where $\mathbf{n}$ is the unit normal vector. The vector equation of the roller surface in $\sigma_0$ is:

$$ \mathbf{r}_0 = x_0 \mathbf{i}_0 + y_0 \mathbf{j}_0 + z_0 \mathbf{k}_0 $$

with

$$ x_0 = R \cos \theta, \quad y_0 = R \sin \theta, \quad z_0 = u $$

where $u$ and $\theta$ are parameters, and $R$ is the radius of the roller. This parameterization is fundamental for deriving the meshing equations in screw gears.

The transformation between coordinate systems is achieved through rotation matrices. For the worm, the transformation from $\sigma_1’$ to $\sigma_1$ is given by:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{i}_1 \\ \mathbf{j}_1 \\ \mathbf{k}_1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \mathbf{M}_{11′} \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{i}_1′ \\ \mathbf{j}_1′ \\ \mathbf{k}_1′ \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

where

$$ \mathbf{M}_{11′} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos \varphi_1 & -\sin \varphi_1 & 0 & 0 \\ \sin \varphi_1 & \cos \varphi_1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

Here, $\varphi_1$ is the rotation angle of the worm. Similarly, for the worm wheel, the transformation from $\sigma_2’$ to $\sigma_2$ is:

$$ \mathbf{M}_{22′} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos \varphi_2 & -\sin \varphi_2 & 0 & 0 \\ \sin \varphi_2 & \cos \varphi_2 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

with $\varphi_2$ as the rotation angle of the worm wheel. The relationship between $\varphi_1$ and $\varphi_2$ is defined by the transmission ratio $i_{12} = \omega_1 / \omega_2 = Z_2 / Z_1$, where $Z_1$ is the number of worm threads and $Z_2$ is the number of worm wheel teeth. Thus, $\varphi_2 = i_{21} \varphi_1$ where $i_{21} = 1/i_{12}$. The transformation from $\sigma_1’$ to $\sigma_2’$ is derived as:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{i}_2′ \\ \mathbf{j}_2′ \\ \mathbf{k}_2′ \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \mathbf{M}_{2’1} \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{i}_1′ \\ \mathbf{j}_1′ \\ \mathbf{k}_1′ \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

where

$$ \mathbf{M}_{2’1} = \begin{bmatrix} -\cos \varphi_1 \cos \varphi_2 & \sin \varphi_1 \cos \varphi_2 & -\sin \varphi_2 & A \cos \varphi_2 \\ \cos \varphi_1 \sin \varphi_2 & -\sin \varphi_1 \sin \varphi_2 & -\cos \varphi_2 & -A \sin \varphi_2 \\ -\sin \varphi_1 & -\cos \varphi_1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

Additionally, the transformation from the worm wheel moving coordinate $\sigma_2’$ to the active frame $\sigma_p$ is expressed as:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{i}_p \\ \mathbf{j}_p \\ \mathbf{k}_p \end{bmatrix} = \mathbf{A}_{p2′} \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{i}_2′ \\ \mathbf{j}_2′ \\ \mathbf{k}_2′ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & -\sin \theta & \cos \theta \\ -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \cos \theta & \sin \theta \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{i}_2′ \\ \mathbf{j}_2′ \\ \mathbf{k}_2′ \end{bmatrix} $$

These transformations are crucial for analyzing the relative motion and contact conditions in screw gears.

The relative velocity and angular velocity between the worm and worm wheel are key to understanding the meshing dynamics. Let $\mathbf{r}_0$ be the position vector of contact point $P$ in $\sigma_0$, $\mathbf{r}_1’$ in $\sigma_1’$, and $\mathbf{r}_2’$ in $\sigma_2’$. The relative velocity vector $\mathbf{V}^{(1’2′)}$ is given by:

$$ \mathbf{V}^{(1’2′)} = \frac{d\boldsymbol{\xi}}{dt} + \boldsymbol{\omega}^{(1’2′)} \times \mathbf{r}_1′ – \boldsymbol{\omega}_2′ \times \boldsymbol{\xi} $$

where $\boldsymbol{\xi}$ is the vector of center distance $A$ in $\sigma_2$. After transformation to the active frame $\sigma_p$, the components of relative velocity are:

$$ \mathbf{V}^{(1’2′)} = V^{(1’2′)}_1 \mathbf{e}_1 + V^{(1’2′)}_2 \mathbf{e}_2 + V^{(1’2′)}_n \mathbf{n} $$

with

$$ V^{(1’2′)}_1 = -B_2 \sin \theta + B_3 \cos \theta, \quad V^{(1’2′)}_2 = -B_1, \quad V^{(1’2′)}_n = B_2 \cos \theta + B_3 \sin \theta $$

where $B_1$, $B_2$, and $B_3$ are functions of geometric parameters and angles. The relative angular velocity vector $\boldsymbol{\omega}^{(1’2′)}$ is:

$$ \boldsymbol{\omega}^{(1’2′)} = \omega^{(1’2′)}_1 \mathbf{e}_1 + \omega^{(1’2′)}_2 \mathbf{e}_2 + \omega^{(1’2′)}_n \mathbf{n} $$

where

$$ \omega^{(1’2′)}_1 = \cos \varphi_2 \sin \theta – i_{21} \cos \theta, \quad \omega^{(1’2′)}_2 = \sin \varphi_2, \quad \omega^{(1’2′)}_n = -\cos \theta \cos \varphi_2 – i_{21} \sin \theta $$

These expressions form the basis for deriving the meshing function in screw gears.

The meshing function and equation are derived from the condition that the normal component of relative velocity at the contact point must be zero. According to gear theory, the meshing function $\Phi$ is defined as:

$$ \Phi = \mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{V}^{(1’2′)} = V^{(1’2′)}_n $$

Substituting the expressions, we obtain:

$$ \Phi = M_1 \cos \varphi_2 + M_2 \sin \varphi_2 + M_3 $$

where

$$ M_1 = \sin \theta (a_2 – u), \quad M_2 = 0, \quad M_3 = -i_{21} \cos \theta (a_2 – u) – A \sin \theta $$

The meshing equation is then:

$$ \Phi = M_1 \cos \varphi_2 + M_2 \sin \varphi_2 + M_3 = 0 $$

This equation governs the contact conditions between the worm and worm wheel in screw gears. For a given $\varphi_2$, the contact line on the roller surface can be determined by combining the roller equation and the meshing equation:

$$ \mathbf{r}_0 = x_0 \mathbf{i}_0 + y_0 \mathbf{j}_0 + z_0 \mathbf{k}_0, \quad u = f(\theta, \varphi_2) = \frac{P_1}{P_2}, \quad \varphi_2 = \text{constant} $$

where $P_1$ and $P_2$ are parameters derived from the geometry. The contact lines are nearly straight, indicating favorable meshing characteristics. In this screw gear design, multiple tooth pairs are engaged simultaneously, enhancing load distribution.

The worm tooth surface is generated as the envelope of the roller surface family. The worm tooth surface equation in $\sigma_1’$ is:

$$ \mathbf{r}_1′ = x_1 \mathbf{i}_1′ + y_1 \mathbf{j}_1′ + z_1 \mathbf{k}_1′ $$

with

$$ \begin{aligned} x_1 &= -\cos \varphi_1 \cos \varphi_2 (a_2 – z_0) + \cos \varphi_1 \sin \varphi_2 x_0 – y_0 \sin \varphi_1 + A \cos \varphi_1 \\ y_1 &= \sin \varphi_1 \cos \varphi_2 (a_2 – z_0) – \sin \varphi_1 \sin \varphi_2 x_0 – y_0 \cos \varphi_1 – A \sin \varphi_1 \\ z_1 &= -\sin \varphi_2 (a_2 – z_0) – \cos \varphi_2 x_0 \end{aligned} $$

where $\mathbf{r}_0 = x_0 \mathbf{i}_0 + y_0 \mathbf{j}_0 + z_0 \mathbf{k}_0$, $u = P_1 / P_2$, and $\varphi_2 = i_{21} \varphi_1$ with $-\pi \leq \varphi_1 \leq \pi$. This equation describes the precise geometry of the worm teeth, which is essential for manufacturing and analysis of screw gears.

To evaluate the performance of this screw gear system, several key parameters are analyzed: induced normal curvature, lubrication angle, relative entrainment velocity, and self-rotation angle. These parameters influence the efficiency, wear, and lubrication conditions in screw gears.

The induced normal curvature $k_\delta^{(1’2′)}$ is calculated using the active frame method. It represents the curvature difference between the two surfaces at the contact point and affects the stress distribution. The formula is:

$$ k_\delta^{(1’2′)} = -k_\delta^{(2’1′)} = -\frac{ \left( \omega^{(1’2′)}_2 + V^{(1’2′)}_1 / R \right)^2 + \left( \omega^{(1’2′)}_1 \right)^2 }{ \psi } $$

where $\psi$ is a determinant involving velocity and angular velocity components. For typical parameters, the induced normal curvature ranges from 0.079 mm⁻¹ to 0.17 mm⁻¹, indicating good surface conformity compared to traditional screw gears.

The lubrication angle $\mu$ is defined as the angle between the tangent to the contact line and the relative velocity direction. A value close to 90° suggests optimal lubrication conditions. It is given by:

$$ \mu = \arcsin \left( \frac{ -V^{(1’2′)}_1 (V^{(1’2′)}_1 / R – \omega^{(1’2′)}_2) + V^{(1’2′)}_2 \omega^{(1’2′)}_1 }{ \sqrt{ (V^{(1’2′)}_1)^2 + (V^{(1’2′)}_2)^2 } \sqrt{ (V^{(1’2′)}_1 / R – \omega^{(1’2′)}_2)^2 + (\omega^{(1’2′)}_1)^2 } } \right) $$

In this screw gear design, $\mu$ remains between 89° and 90°, demonstrating excellent lubrication potential.

The relative entrainment velocity $V_{jx}$ is half the sum of the velocities of the two surfaces along the normal direction at the contact point. Higher values promote the formation of hydrodynamic oil films. It is computed as:

$$ V_{jx} = 0.5 (V_{1’\sigma} + V_{2’\sigma}) $$

where

$$ V_{1’\sigma} = \frac{ V_{1’1} (V^{(1’2′)}_1 / R – \omega^{(1’2′)}_2) + V_{1’2} \omega^{(1’2′)}_1 }{ \sqrt{ (V^{(1’2′)}_1 / R – \omega^{(1’2′)}_2)^2 + (\omega^{(1’2′)}_1)^2 } } $$

and similarly for $V_{2’\sigma}$. For this screw gear system, $V_{jx}$ varies from 10 mm/s to 23 mm/s, facilitating effective lubrication.

The self-rotation angle $\mu_{z0}$ is the angle between the relative velocity vector and the roller axis $\mathbf{k}_0$. A value near 90° indicates favorable conditions for roller self-rotation, which reduces sliding friction. It is defined as:

$$ \mu_{z0} = \arccos \left( \frac{ \mathbf{k}_0 \cdot \mathbf{v}^{(12)} }{ |\mathbf{v}^{(12)}| } \right) = \arccos \left( \frac{ v^{(12)}_2 }{ \sqrt{ (v^{(12)}_1)^2 + (v^{(12)}_2)^2 } } \right) $$

In this design, $\mu_{z0}$ ranges from 84.5° to 90°, showing that the rollers can self-rotate efficiently, a key advantage in screw gears.

To summarize the geometric and operational parameters, the following table provides typical values used in the analysis of this screw gear system:

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Center distance | $A$ | 100 | mm |

| Worm threads | $Z_1$ | 1 | – |

| Worm wheel teeth | $Z_2$ | 40 | – |

| Transmission ratio | $i_{12}$ | 40 | – |

| Roller radius | $R$ | 10 | mm |

| Coordinates of $O_0$ in $\sigma_2$ | $(a_2, b_2, c_2)$ | (50, 0, 0) | mm |

Another table compares the performance metrics of this screw gear design with traditional screw gears:

| Metric | Roller Enveloping End Face Meshing Screw Gears | Traditional Screw Gears | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Induced normal curvature | 0.079 – 0.17 mm⁻¹ | ~0.2 mm⁻¹ | Reduced by 0.03 – 0.121 mm⁻¹ |

| Lubrication angle | 89° – 90° | 80° – 88° | Increased by 1° – 10° |

| Relative entrainment velocity | 10 – 23 mm/s | Varies, often lower | Enhanced film formation |

| Self-rotation angle | 84.5° – 90° | ~76° | Increased by 8.5° – 14° |

The mathematical derivations presented here rely on differential geometry and gear meshing theory. The use of coordinate transformations and active frames simplifies the analysis of complex surfaces in screw gears. For instance, the meshing equation can be solved numerically to determine the contact patterns. Additionally, the induced normal curvature is derived from the second fundamental forms of the surfaces, which relate to the principal curvatures. In practice, these calculations aid in optimizing the design parameters for specific applications, such as high-precision machinery or heavy-duty transmissions. The roller enveloping end face meshing screw gears exhibit superior characteristics due to their unique geometry. The end face engagement allows for a larger contact area, which distributes loads more evenly and reduces stress concentrations. This is particularly beneficial in screw gears used for high-torque applications. Moreover, the rolling contact between the rollers and worm teeth minimizes sliding friction, leading to lower energy losses and less heat generation. The self-rotation of rollers further enhances this effect by allowing the rollers to adjust dynamically during operation. These features collectively contribute to the durability and efficiency of screw gears.

In terms of manufacturing, the worm tooth surface can be generated using CNC machining based on the derived equations. The roller-based worm wheel simplifies production, as standard rollers and bearings can be utilized. This reduces costs compared to traditional bronze worm wheels. However, precision assembly is crucial to maintain the symmetric meshing and proper alignment. The design also allows for adjustable preload to eliminate backlash, which is essential for applications requiring high positional accuracy. These practical considerations make roller enveloping end face meshing screw gears a viable option for modern industrial systems.

From a theoretical perspective, the meshing analysis reveals insights into the kinematics and dynamics of screw gears. The relative velocity components influence the sliding and rolling ratios, which affect wear patterns. The lubrication angle analysis suggests that elastohydrodynamic lubrication (EHL) conditions can be achieved, reducing direct metal-to-metal contact. The relative entrainment velocity supports the formation of thick oil films, especially when using suitable lubricants. These factors are critical for predicting the lifespan and performance of screw gears in real-world conditions.

Future research could explore the effects of manufacturing errors, such as misalignment or surface roughness, on the meshing behavior. Thermal analysis could also be conducted to assess heat dissipation in continuous operation. Additionally, experimental validation through prototype testing would confirm the theoretical predictions. The integration of smart materials or coatings could further enhance the performance of screw gears. As technology advances, such innovative screw gear designs may become standard in aerospace, robotics, and automotive industries where reliability and efficiency are paramount.

In conclusion, the roller enveloping end face meshing screw gear represents a significant advancement in transmission technology. By combining roller enveloping and end face engagement, it achieves rolling contact characteristics that reduce friction, wear, and heat generation. The mathematical model and meshing theory provide a solid foundation for analysis and optimization. Key parameters like induced normal curvature, lubrication angle, relative entrainment velocity, and self-rotation angle demonstrate superior performance compared to traditional screw gears. This design not only improves efficiency and lifespan but also offers practical benefits in manufacturing and assembly. As screw gears continue to evolve, such innovations will play a crucial role in meeting the demands of modern engineering applications. I believe that further development and adoption of this technology will lead to more reliable and sustainable mechanical systems.