In my extensive experience within heavy machinery manufacturing, few components present as persistent and costly a challenge as large-diameter spiral bevel gears, often called “crown” or “pan” gears. These critical power transmission elements are central to equipment like workover rigs, where their failure can lead to catastrophic downtime. The primary source of failure often isn’t the design or material but the insidious and complex realm of heat treatment defects. I have dedicated significant effort to understanding and mitigating these distortions, transitioning from trial-and-error methods to a controlled, scientific process. The journey from uncontrolled warping to precision-controlled quenching is a testament to the intricate dance between metallurgy, mechanics, and thermal physics.

The core challenge with these pan-shaped gears lies in their asymmetric geometry. One side is a massive, solid flat back, while the other comprises the intricate, thin-webbed spiral teeth. When subjected to the intense thermal cycles of carburizing and quenching, these two faces experience drastically different realities. They heat at different rates, cool at different speeds, and consequently, develop different magnitudes and distributions of internal stress. If left unchecked, these stresses manifest as severe geometrical distortions, primarily a dishing or cupping of the flat back and an ovalization of the central bore. These specific heat treatment defects directly compromise the gear’s meshing accuracy, load distribution, and acoustic performance, rendering the part useless regardless of its surface hardness or case depth.

The fundamental physics behind these distortions can be broken down into two competing stress systems: thermal stress and transformation (phase) stress. During quenching, the rapid cooling of the surface layers relative to the core creates significant thermal contraction differentials. This generates thermal stress, which can be approximated for a simple plate by:

$$\sigma_{thermal} \approx E \cdot \alpha \cdot \Delta T$$

where \(E\) is Young’s modulus, \(\alpha\) is the thermal expansion coefficient, and \(\Delta T\) is the temperature gradient. In our pan gear, the thin-toothed side and the thick back cool at radically different rates (\( \Delta T_{teeth} > \Delta T_{back} \)), creating a complex, non-uniform thermal stress field that tries to dish the gear.

Simultaneously, as the austenite transforms to martensite, the associated volume expansion (typically 1-4%) generates transformation stress. The martensite start (Ms) temperature is critical here. The transformation stress, particularly the compressive stress on the surface, can be conceptualized as:

$$\sigma_{phase} \propto \frac{\Delta V \cdot E}{3(1-\nu)}$$

where \(\Delta V\) is the volumetric change and \(\nu\) is Poisson’s ratio. The key is that the magnitude of this compressive stress is greater in the carburized, hardenable tooth region than in the less-hardenable thick back. This stress system tries to deform the gear in the opposite direction to the thermal stress. The final distortion is the net, often unpredictable, result of these two opposing forces. Early in my work, I hypothesized that by manipulating the cooling conditions, I could align these stress systems to counteract each other. This led to the initial experimentation with free-quenching methods.

The first approach involved horizontal stacking in the furnace, with spacers between gears. The idea was to promote oil flow through the bore to reduce ovality and encourage oil heated by the teeth to wash over the back plane of the gear below, attempting to equalize cooling. The second, more sophisticated method involved vertically clamping two gears back-to-back with a spacer, aiming for symmetrical heat extraction. Both methods failed to contain the heat treatment defects. The results were telling: while some improvements in bore roundness were noted, the back-face runout or dish distortion consistently exceeded the tight tolerance of 0.05mm. This was a clear indicator that in free quenching, the local and instantaneous cooling rates were still too heterogeneous to control the complex stress state. The fundamental asymmetry of the part defeated symmetrical cooling strategies.

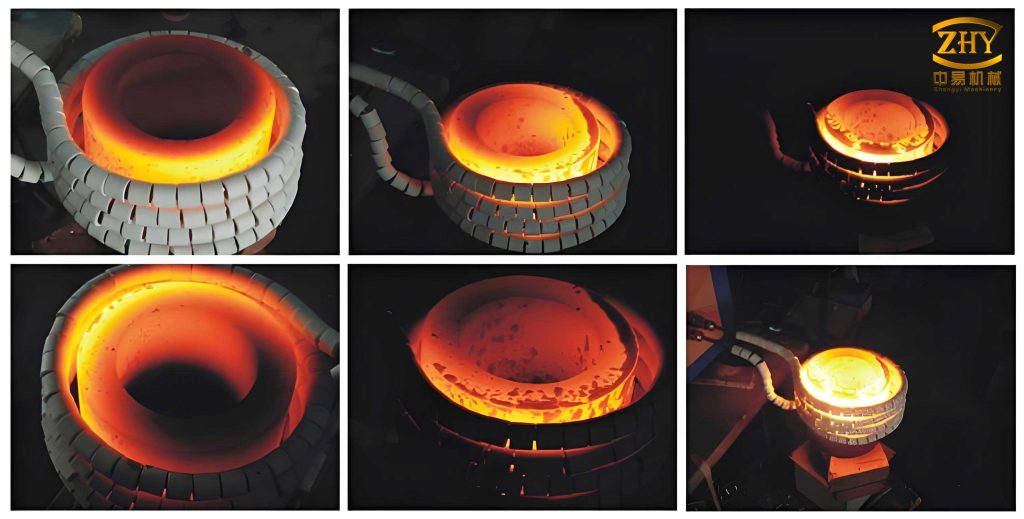

This failure forced a strategic pivot. It became unequivocally clear that to combat these specific heat treatment defects, the component needed to be physically constrained during the most critical phase—the martensitic transformation. The solution lay in press quenching, or die quenching. Utilizing a standard quenching press, the goal was to design a fixture that would hold the gear in its nominal geometrical shape against the immense internal stresses generated during cooling. The design philosophy moved from influencing stress generation to directly opposing its distortive effects with mechanical force.

The success of press quenching hinges on a meticulously designed fixture and a precise process protocol. The fixture must address multiple distortion modes simultaneously. For our pan gear, the critical modes were: 1) Back-face dishing (runout), 2) Bore ovality, and 3) Bore diameter growth/shrinkage. The fixture I helped implement uses a multi-zone pressure application system. A central conical punch applies force to control the bore diameter and concentricity. A separate inner pressure ring acts on the gear’s web area near the bore, and an outer pressure ring acts on the outer rim/flange area. The pressure in each of these zones is independently controllable via hydraulic valves. This allows for real-time, recipe-driven correction of specific distortion trends.

The process sequence is vital. The gear, after carburizing and slow cooling, is reheated in a protective atmosphere to the austenitizing temperature (typically 840-860°C for 20CrMnTi). It is then transferred rapidly to the press. The sequence must ensure the locating die contacts the bore before significant cooling occurs, establishing correct alignment. Then, the pressure zones are activated in a controlled sequence to clamp the gear before martensite starts to form (above the Ms point, ~300-350°C). The part is held under pressure until it is fully cooled, often below 100°C, to ensure the martensitic transformation is complete and stable. This method doesn’t eliminate the internal stresses; it plastically deforms the part *during* transformation to compensate for them, resulting in a net shape that is within tolerance.

The true power of this system is its adjustability. By analyzing the distortion patterns from previous batches, one can create a feedback loop to fine-tune the pressure parameters. This empirical database is crucial for mastering heat treatment defects. The adjustments are logical and direct, as summarized in the table below:

| Observed Distortion (Heat Treatment Defect) | Primary Corrective Adjustment | Supporting Process Adjustment |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive Inner Runout (Bore wobble) | Increase pressure on the inner thrust ring. | Ensure uniform heating prior to quench. |

| Excessive Outer Runout (Flange wobble) | Increase pressure on the outer thrust ring. | Check for part seating on the lower die. |

| Bore Diameter Too Large | Increase pressure from the central punch. | Consider a slight reduction in austenitizing temperature. |

| Bore Diameter Too Small | Decrease pressure from the central punch. Increase inner/outer ring pressure to balance. | Implement a brief dwell (pre-cooling) before pressure application. |

| Persistent Back-face Dish | Simultaneously increase inner and outer ring pressures to flatten. | Verify the flatness of the press die surfaces. |

The results from implementing this controlled press quench were transformative. The statistical process control data showed a dramatic reduction in variation. For a batch of gears processed this way, key metrics like bore roundness (≤0.03mm), inner runout (≤0.04mm), and outer runout (≤0.05mm) were consistently achieved, well within the specification limits. The most compelling evidence was the meshing contact pattern. Before controlled quenching, the pattern was erratic, biased towards the toe or heel of the tooth, indicating twist and distortion. After press quenching, the contact pattern was a perfect, centered ellipse across the tooth flank, demonstrating excellent gear geometry and alignment. This directly translates to higher load capacity, smoother operation, and longer service life—the ultimate victory over heat treatment defects.

To put this into a broader perspective, it’s useful to compare the various strategies for managing distortion, their complexity, and effectiveness. The following table encapsulates the evolution of the approach:

| Control Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Complexity/Cost | Effectiveness on Complex Asymmetrical Gears | Primary Defects Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free Quenching (Horizontal/Vertical Stack) | Influences cooling symmetry & fluid dynamics. | Low | Low to Moderate. Unreliable for severe asymmetry. | General warping, some bore distortion. |

| Hot Sizing (Post-Quench Correction) | Plastic deformation of the hardened part to correct shape. | Moderate | Moderate. Risk of micro-cracking, does not relieve stress. | Gross geometric errors, runout. |

| Press/Die Quenching | Mechanically constrains part during phase transformation. | High (Fixture & Press) | Very High. Directly counters transformation stresses. | All forms of warping, dishing, ovality, size change. |

| Carburize & High-Temp Temper before Final Hardening | Stress relief & grain refinement between cycles. | Moderate (Extra Cycle) | Moderate as a standalone method. Excellent when combined with press quench. | Reduces overall stress magnitude, improving predictability. |

| Simulation-Driven Fixture Design | Uses FEM to predict distortion and optimize fixture geometry/pressure zones. | Very High (Software & Expertise) | Theoretical Maximum. Enables first-time-right fixture design. | All defects, addressed proactively in design phase. |

The choice of material, 20CrMnTi in this case, is also integral to the strategy. Its excellent hardenability, fine grain structure, and good carburizing response provide a stable base. However, the best material cannot compensate for poor thermal process control. The complete, optimized process flow I now advocate is: Material Certification → Precision Machining (leaving adequate stock for distortion) → Carburizing → Slow Cool or Rehearth → Re-Austenitize under Protection → Controlled Press Quench → Low-Temperature Tempering → Final Precision Grinding (if required). Each step is a defensive layer against heat treatment defects.

Looking forward, the control of these defects is moving towards digitalization. The use of Finite Element Method (FEM) software to simulate the coupled thermal, metallurgical, and mechanical phenomena during quenching is the next frontier. A simplified constitutive model for simulation might incorporate:

$$ \sigma_{total} = f(\epsilon_{thermal}, \epsilon_{phase}, \epsilon_{plastic}, T, t) $$

where the total stress is a function of thermal strain, phase transformation strain, plastic strain, temperature, and time. By inputting the gear’s precise geometry, material properties (including CCT diagrams), and proposed fixture design, one can virtually prototype the quenching process. The software predicts distortion patterns, allowing for the optimization of pressure zones, die contours, and quenching parameters *before* cutting any metal. This simulation-led approach promises to reduce the empirical tuning time and further shrink the margins of error, virtually eliminating prototyping batches plagued by heat treatment defects.

In conclusion, the battle against distortion in large spiral bevel gears is won through a combination of deep metallurgical understanding, precise mechanical intervention, and systematic process control. The journey from unreliable free quenching to deterministic press quenching is a necessary evolution for manufacturing high-performance gears. It teaches a critical lesson: one cannot merely react to heat treatment defects; one must design the entire thermal-mechanical process to govern them. The successful production of multiple gear sets with consistent, superlative quality stands as proof that these complex distortions are not an inevitability but a controllable variable. The key lies in respecting the immense power of transformation stresses and having the mechanical means to harness them, ensuring the final geometry emerges from the quench bath not as a distorted shadow of its intended self, but as a precision component ready for a long life of reliable service.