In the design of large-scale machinery, such as hydraulic presses, the need for multiple hydraulic actuators to drive a single mechanism is common due to high load demands or spatial constraints. This necessitates synchronization systems that ensure these actuators move with identical displacement, force, or speed. As an engineer specializing in mechanical design, I often encounter challenges in achieving precise synchronization, particularly in applications like press machines where accuracy is critical for uniform pressure distribution and operational efficiency. In this article, I will explore the design methodology for synchronization mechanisms, with a focused emphasis on rack and pinion gears systems. Rack and pinion gears are widely favored for their simplicity, reliability, and effectiveness in maintaining synchronization. Throughout this discussion, I will delve into the principles, structural design, and analytical checks for strength and stiffness, incorporating formulas and tables to summarize key concepts. The goal is to provide a comprehensive guide that addresses the intricacies of designing rack and pinion gears for press machines, ensuring they meet rigorous performance standards.

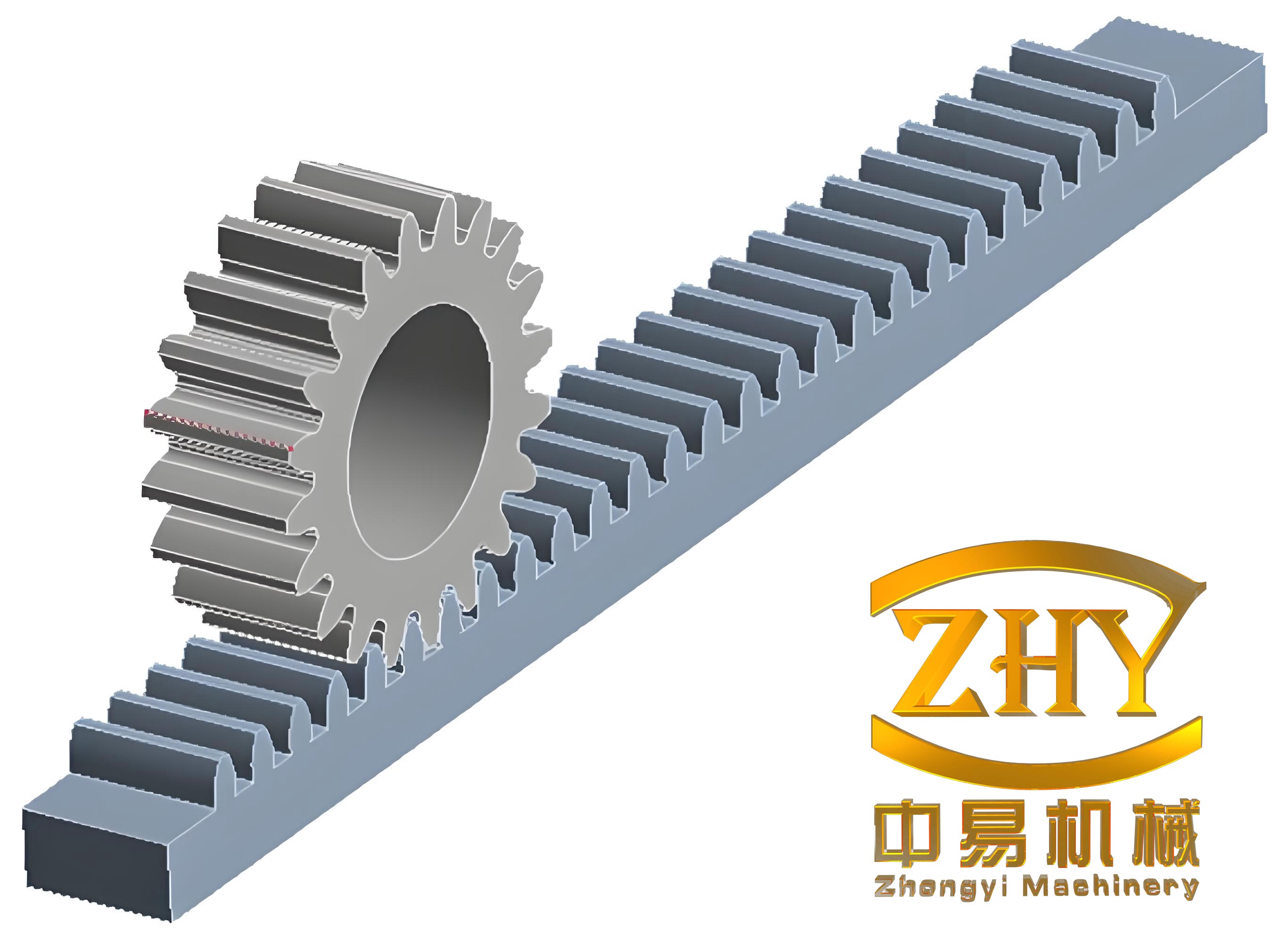

Synchronization mechanisms can be broadly categorized into mechanical, hydraulic, and electro-hydraulic types. For mechanical systems, three common approaches are typically employed: rigid guidance systems, four-bar linkage synchronization mechanisms, and rack and pinion gears synchronization mechanisms. Rigid guidance is suitable for smaller presses with moderate synchronization requirements, but it lacks the precision needed for high-accuracy applications. Four-bar linkage mechanisms leverage the parallel motion principle of parallelogram linkages, offering simplicity and low cost in design and manufacturing. However, the rack and pinion gears system stands out as a prevalent choice due to its robust performance and ease of implementation. Rack and pinion gears mechanisms operate by converting linear motion into rotational motion or vice versa, ensuring that multiple actuators remain in sync through mechanical interlocking. There are two primary configurations: one where the gear is fixed and the rack floats, and another where the rack is fixed and the gear floats. Both variants offer distinct advantages in terms of installation and synchronization reliability. In press machines, where synchronization accuracy is paramount, rack and pinion gears systems are often integrated to enhance precision under eccentric loads. I will now detail the design process for these rack and pinion gears systems, starting with their working principles and moving into mechanical design considerations.

The core principle of rack and pinion gears synchronization lies in the meshing interaction between a gear (pinion) and a linear rack. When hydraulic cylinders act on the racks, their linear movements are transmitted to the gear, which rotates accordingly. If multiple racks are connected to the same gear, any discrepancy in their displacements causes the gear to rotate, thereby equalizing the motion through torque transmission. This ensures that all connected cylinders move synchronously. For instance, in a press with two hydraulic cylinders, if one cylinder advances faster, it drives the rack to rotate the gear, which in turn pulls the slower rack forward, maintaining alignment. This mechanism is highly effective in compensating for minor misalignments and load imbalances. The rack and pinion gears design is particularly advantageous because it minimizes backlash when properly engineered, and it can be scaled for large presses with wide tables. To illustrate, consider a press with a table width of 1640 mm: the rack and pinion gears system can be designed to span this distance, with the gear shaft acting as the synchronizing element. The synchronization accuracy, often specified as a tolerance (e.g., 0.1 mm), depends on the stiffness of the gear shaft and the precision of the gear teeth engagement. Throughout this article, I will refer to rack and pinion gears as the key component, emphasizing their role in achieving precise motion control.

Turning to the mechanical structure design, a rack and pinion gears synchronization mechanism comprises several critical components: the gear (pinion), rack, key, shaft, shaft end plates, bearing seats, bearings, and bearing covers. The gear and rack are typically made of hardened steel to withstand high loads and reduce wear. The key is used to transmit torque from the gear to the shaft, ensuring a secure connection. The shaft, which is the central rotating element, must be designed with adequate diameter to resist torsional stresses. Bearing seats and covers house the bearings, providing support and alignment for the shaft, while shaft end plates axially locate the gear. In practice, the gear is mounted on the shaft using a keyway, and the shaft is supported by bearings at both ends to minimize deflection. The racks are attached to the moving parts of the press, such as the platen or crosshead, and they engage with the gear teeth along their length. Proper lubrication is essential to reduce friction and prolong the life of the rack and pinion gears. Below, I present a table summarizing the key components and their functions in a rack and pinion gears synchronization system:

| Component | Function | Design Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Gear (Pinion) | Converts linear motion of racks to rotational motion | Module, number of teeth, material hardness, backlash control |

| Rack | Provides linear motion input from hydraulic cylinders | Length, tooth profile, alignment with gear, mounting |

| Shaft | Transmits torque and supports gear | Diameter based on strength and stiffness, material selection |

| Key | Transmits torque between gear and shaft | Size, fit, shear strength |

| Bearings | Support shaft and reduce friction | Type (e.g., roller bearings), load capacity, lubrication |

| Bearing Covers | Seal and protect bearings | Fit, sealing materials, ease of maintenance |

To ensure the rack and pinion gears system operates reliably under load, both strength and stiffness of the shaft must be verified through analytical calculations. The shaft is subjected to torsional moments due to the forces from the hydraulic cylinders acting through the racks. Assuming a press with two cylinders, each exerting a force \( F \), and a gear with pitch diameter \( d \), the torque \( T \) on the shaft is given by:

$$ T = \frac{F \cdot d}{2} $$

This torque induces shear stresses in the shaft, which must not exceed the allowable shear stress of the material. For a solid circular shaft of diameter \( D \), the polar moment of inertia \( I_p \) and torsional section modulus \( W_p \) are:

$$ I_p = \frac{\pi}{32} D^4 $$

$$ W_p = \frac{\pi}{16} D^3 $$

According to material mechanics, the maximum shear stress \( \tau_{\text{max}} \) occurs at the outer surface and is calculated as:

$$ \tau_{\text{max}} = \frac{T}{W_p} = \frac{16T}{\pi D^3} $$

The strength condition requires that:

$$ \tau_{\text{max}} \leq [\tau] $$

where \( [\tau] \) is the allowable shear stress of the shaft material, such as 108 MPa for 45-grade steel. Rearranging this inequality provides the minimum shaft diameter for strength:

$$ D \geq \sqrt[3]{\frac{16T}{\pi [\tau]}} = \sqrt[3]{\frac{8F d}{\pi [\tau]}} $$

This equation ensures the rack and pinion gears shaft can withstand the operational torques without failure. However, strength alone is insufficient; stiffness must also be considered to maintain synchronization accuracy. The torsional stiffness of the shaft determines how much it twists under load, which directly affects the displacement error between the racks. The angle of twist \( \phi \) over shaft length \( L \) is given by:

$$ \phi = \frac{T L}{G I_p} $$

where \( G \) is the shear modulus of the material (e.g., 80 GPa for steel). If the synchronization accuracy is specified as a maximum allowable displacement difference \( t \) (e.g., 0.1 mm), then the twist must satisfy:

$$ \phi \cdot \frac{d}{2} \leq t $$

Substituting the expressions for \( \phi \) and \( I_p \), we derive the stiffness condition for the shaft diameter:

$$ \frac{T L}{G I_p} \cdot \frac{d}{2} \leq t \implies \frac{F d^2 L}{4 G \cdot \frac{\pi}{32} D^4} \leq t $$

Simplifying yields:

$$ D \geq \sqrt[4]{\frac{8 F d^2 L}{t G \pi}} $$

This ensures that the rack and pinion gears system meets the precision requirements. In practice, the larger diameter from the strength and stiffness calculations should be selected for the shaft design. To illustrate this process, I will now walk through a detailed design example for a press machine using rack and pinion gears synchronization.

Consider a press with a design force of \( 8 \times 10^4 \, \text{N} \) distributed across two hydraulic cylinders, each providing \( F = 4 \times 10^4 \, \text{N} \). The table width is 1640 mm, so the shaft length \( L = 1.64 \, \text{m} \). The synchronization accuracy required is \( t = 0.1 \, \text{mm} = 0.1 \times 10^{-3} \, \text{m} \). The rack and pinion gears are selected with a module \( m = 3 \, \text{mm} \) and a gear tooth count \( Z = 20 \), giving a pitch diameter \( d = m Z = 60 \, \text{mm} = 0.06 \, \text{m} \). The shaft material is 45-grade steel with allowable shear stress \( [\tau] = 108 \, \text{MPa} = 108 \times 10^6 \, \text{Pa} \) and shear modulus \( G = 80 \, \text{GPa} = 80 \times 10^9 \, \text{Pa} \). First, calculate the torque on the shaft:

$$ T = \frac{F d}{2} = \frac{4 \times 10^4 \times 0.06}{2} = 1200 \, \text{N} \cdot \text{m} $$

Now, determine the minimum shaft diameter for strength using the strength condition:

$$ D_{\text{strength}} \geq \sqrt[3]{\frac{8 F d}{\pi [\tau]}} = \sqrt[3]{\frac{8 \times 4 \times 10^4 \times 0.06}{\pi \times 108 \times 10^6}} $$

Computing step-by-step:

$$ \text{Numerator} = 8 \times 4 \times 10^4 \times 0.06 = 19200 $$

$$ \text{Denominator} = \pi \times 108 \times 10^6 \approx 3.1416 \times 108 \times 10^6 = 3.393 \times 10^8 $$

$$ \text{Ratio} = \frac{19200}{3.393 \times 10^8} \approx 5.66 \times 10^{-5} $$

$$ D_{\text{strength}} \geq \sqrt[3]{5.66 \times 10^{-5}} \approx 0.0384 \, \text{m} = 38.4 \, \text{mm} $$

Thus, for strength alone, a shaft diameter of about 40 mm suffices. Next, check the stiffness requirement using the stiffness condition:

$$ D_{\text{stiffness}} \geq \sqrt[4]{\frac{8 F d^2 L}{t G \pi}} = \sqrt[4]{\frac{8 \times 4 \times 10^4 \times (0.06)^2 \times 1.64}{0.1 \times 10^{-3} \times 80 \times 10^9 \times \pi}} $$

Compute the numerator:

$$ 8 \times 4 \times 10^4 = 3.2 \times 10^5 $$

$$ d^2 = (0.06)^2 = 0.0036 $$

$$ 3.2 \times 10^5 \times 0.0036 = 1152 $$

$$ 1152 \times 1.64 = 1889.28 $$

Denominator:

$$ t G \pi = 0.1 \times 10^{-3} \times 80 \times 10^9 \times \pi = 0.1 \times 10^{-3} \times 8 \times 10^{10} \times \pi = 8 \times 10^6 \times \pi \approx 2.513 \times 10^7 $$

Ratio:

$$ \frac{1889.28}{2.513 \times 10^7} \approx 7.52 \times 10^{-5} $$

Now, take the fourth root:

$$ D_{\text{stiffness}} \geq \sqrt[4]{7.52 \times 10^{-5}} \approx 0.0525 \, \text{m} = 52.5 \, \text{mm} $$

Therefore, to meet the synchronization accuracy of 0.1 mm, the shaft diameter must be at least 52.5 mm. Rounding up for safety, we select \( D = 55 \, \text{mm} \). This example highlights how stiffness often governs the design of rack and pinion gears shafts in precision applications, underscoring the importance of rigorous analytical checks.

Beyond the basic calculations, several additional factors influence the design of rack and pinion gears systems. For instance, the gear tooth geometry must be designed to minimize backlash, which can introduce synchronization errors. This involves selecting appropriate pressure angles (commonly 20°) and ensuring precise machining of the rack and pinion gears. Lubrication systems should be integrated to reduce wear and heat generation, especially in high-cycle presses. Moreover, the mounting of the racks must allow for slight adjustments to compensate for installation misalignments. Thermal expansion can also affect performance; using materials with similar coefficients of expansion for the rack and pinion gears helps maintain engagement under temperature variations. In terms of manufacturing, CNC machining is recommended for achieving the required tolerances in rack and pinion gears components. Regular maintenance, including inspection for tooth wear and bearing play, is crucial to sustain synchronization accuracy over time. To further aid designers, I have compiled a table of common materials and their properties for rack and pinion gears in press applications:

| Material | Allowable Shear Stress [τ] (MPa) | Shear Modulus G (GPa) | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 45-Grade Steel | 108 | 80 | General-purpose shafts and gears |

| 40Cr Steel | 120 | 81 | High-strength components |

| 20MnTiB | 150 | 82 | Heavy-duty racks and pinions |

| Cast Iron | 40 | 70 | Low-load, cost-effective systems |

| Stainless Steel | 90 | 77 | Corrosion-resistant environments |

In conclusion, the design of rack and pinion gears synchronization mechanisms for press machines involves a systematic approach that balances mechanical structure, strength, and stiffness. From my experience, the rack and pinion gears system offers a robust solution for achieving precise synchronization, particularly in large presses with wide tables. By applying the formulas for torsional strength and stiffness, engineers can determine appropriate shaft dimensions to meet both safety and accuracy requirements. The design example demonstrated how stiffness considerations often dictate larger shaft diameters to maintain synchronization tolerances. Furthermore, attention to component selection, lubrication, and maintenance ensures long-term reliability of the rack and pinion gears. As technology advances, innovations in materials and manufacturing may enhance the performance of these systems, but the fundamental principles outlined here remain valid. I hope this detailed exploration provides valuable insights for designers working on synchronization challenges in press machinery, emphasizing the critical role of rack and pinion gears in modern industrial applications.