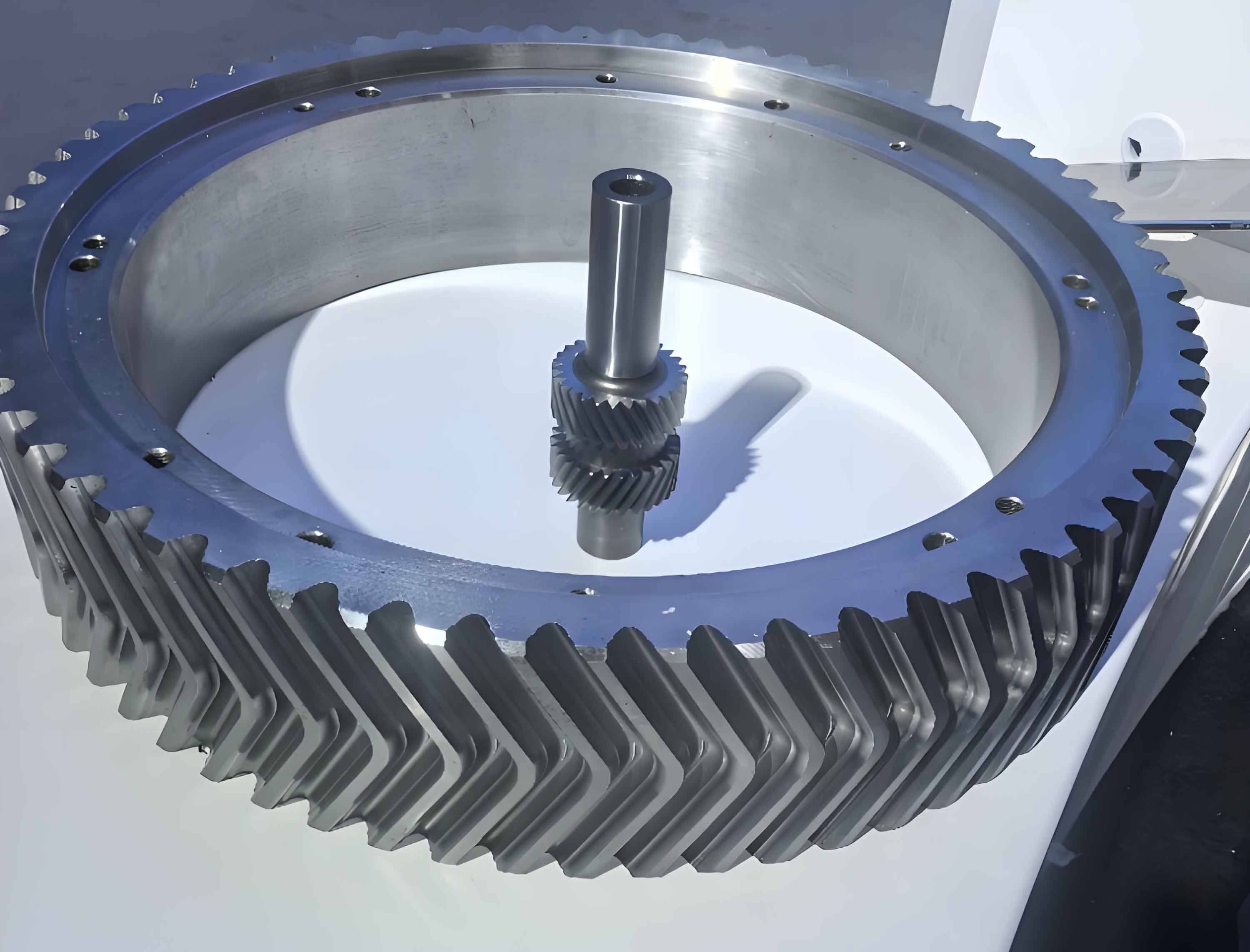

In my extensive experience with heavy-duty rolling mill equipment, the herringbone gear shaft stands out as a critical and costly component. Its failure directly leads to significant production downtime and economic loss. The operational life of these herringbone gears is not determined by a single factor but is the culmination of a chain of interdependent processes: from initial material selection and forging to precise heat treatment and final running-in. This discussion synthesizes practical engineering knowledge to explore a systematic methodology for maximizing their operational lifespan.

The fundamental working principle of a herringbone gear involves the transmission of high torque under severe and fluctuating loads. The tooth flanks are subjected to cyclic contact stress (Hertzian stress), while the tooth roots endure alternating bending stress. Furthermore, dynamic loads arising from the variable nature of the rolling process itself, combined with inevitable manufacturing and assembly inaccuracies, superimpose additional stresses. Consequently, herringbone gears for such applications must possess exceptional contact and bending strength, sufficient impact toughness, high wear resistance, and must operate with minimal noise and high transmission accuracy. Achieving this multifaceted requirement profile hinges on the correct selection of material and the execution of a meticulously designed thermal and mechanical processing regimen.

I. The Paramount Importance of Material Selection and Metallurgical Quality

The journey toward a durable herringbone gear begins with the steel ingot. The material must first exhibit good machinability to achieve the necessary surface finish after cutting. However, more critical are the inherent metallurgical factors, which form the foundation of quality. Defects such as segregation, non-metallic inclusions, and forging cracks are primary determinants of the final performance of herringbone gears.

- Inclusions: Inclusions disrupt the continuity of the metal matrix. Under stress, they act as stress concentrators, initiating micro-cracks either in the adjacent matrix or within the inclusion itself due to their brittleness. Differences in thermal expansion coefficients between inclusions and the steel matrix can further promote micro-cracking during forging and heat treatment. Sulfide inclusions are particularly detrimental, severely reducing transverse reduction of area and impact toughness. The morphology of sulfides can be improved through the addition of elements like titanium or zirconium, or via high-temperature diffusion annealing to spheroidize them, thereby enhancing resistance to brittle fracture. Gaseous impurities, especially hydrogen, are extremely harmful. Hydrogen is the primary cause of flaking (white spots) and can induce “hydrogen embrittlement,” which occurs at hydrogen levels significantly lower than those required to form flakes. Inclusions directly lower fatigue strength; their size is inversely proportional to the material’s fatigue limit. Therefore, selecting material for herringbone gears necessitates a focus on high purity—minimizing the population and size of inclusions. Vacuum-degassed steel is highly preferable.

- Segregation: Chemical segregation leads to significant variation in composition across the forging. This variation causes differences in the time required for phase transformations (like the pearlite transformation) during heat treatment. To ensure complete transformation in all regions, prolonged soaking times may be required, risking austenite grain growth and a consequent drop in strength and toughness. Segregated zones, enriched with carbon, sulfur, phosphorus, and alloying elements, are embrittled and highly prone to cracking during heat treatment. The accumulation of hydrogen and inclusions in these zones exacerbates this risk.

- Forging Practice: Proper forging is non-negotiable. It refines the coarse as-cast dendritic structure, closes voids and porosity to densify the metal, and disperses segregated and inclusion-rich zones to homogenize the structure. Inadequate forging can fail to heal internal micro-defects, instead creating internal forging cracks that catastrophically degrade mechanical properties.

In summary, the base material for herringbone gears must meet stringent quality standards, as summarized in the following table.

| Inspection Item | Acceptable Grade / Condition |

|---|---|

| General Porosity | ≤ Grade 2 |

| Centerline Porosity | ≤ Grade 2 |

| Internal & External Cracks | None |

| Flakes (White Spots) | None |

| Oxide Inclusions | ≤ Grade 2 |

| Sulfide Inclusions | ≤ Grade 2 |

The steel grade itself must, after heat treatment, offer high strength, toughness, wear resistance, and minimal quenching distortion. For herringbone gears, a medium carbon content in the range of 0.40-0.50% is optimal. It should contain alloying elements like Cr, Ni, Mo, and Mn to enhance hardenability; grain-refining elements like Al, V, or Ti; and elements like Mo or W to mitigate temper embrittlement. A classic alloy steel such as 34CrNi3Mo exemplifies a suitable choice, offering excellent hardenability, high tempering stability, and superior mechanical properties after quenching and tempering, making it ideal for heavily loaded herringbone gear shafts.

II. The Critical Role of Quenching and Tempering (Conditioning Treatment)

After rough machining, alloy steel herringbone gear blanks must undergo a full quenching and tempering (QT) treatment. This process aims to produce a uniform and fine tempered sorbitic structure throughout the component. The benefits are threefold: 1) It significantly improves the comprehensive mechanical properties, ensuring the gear tooth core possesses high strength and toughness, which elevates the tooth’s bending strength and impact resistance. 2) It eliminates large, soft blocks of free ferrite which have an extremely low fatigue strength, thereby enhancing resistance to fatigue crack initiation. 3) It creates an ideal pre-conditioned microstructure (fine sorbitte) for the subsequent surface hardening process, allowing for the formation of a uniform and dense hardened case. The hardness of this sorbitic core should be controlled within the range of 250-300 HB. This ensures a gradual, not abrupt, hardness transition from the hardened case to the core, preventing a weak interface layer.

III. The Science and Art of Running-in Herringbone Gears

Prior to final surface hardening, the machined herringbone gear pair must undergo a meticulous running-in (lapping) procedure. The goal is to correct minor surface irregularities from machining and to achieve a contact pattern covering over 90% of the theoretical tooth flank area. This process is conducted in two critical stages:

- Initial Alignment and Lapping: The herringbone gearbox is assembled, and a marking compound (e.g., Prussian blue) is applied to the tooth flanks. The gears are run at low speed to visualize the contact pattern. The pattern is then carefully corrected by minor adjustments or selective polishing. Once the contact is reasonably uniform, a fine abrasive lapping compound is applied to polish the surfaces until they are smooth and the contact area exceeds 90%.

- Light Load Conditioning: The gearbox is connected to the rolling mill drive. An initial period of no-load running (1-2 hours) is followed by processing a single, light-gauge bar. It is imperative to avoid heavy load running-in at this stage. The tooth surface, still in its tempered sorbitic state, has a relatively low hardness (approx. 300 HB, yielding a shear strength $ au_s \approx 0.58 imes 300 ext{ HB} \approx 174 ext{ kgf/mm}^2$). If the applied load generates shear stresses exceeding this value, subsurface plastic deformation and incipient cracks can form.

The physics behind this caution is crucial. The contact pressure between mating teeth creates a complex triaxial stress field. The maximum alternating shear stress $ au_{max}$ does not occur at the surface but at a certain depth below it (the subsurface “danger point”), as illustrated in classic Hertzian contact theory for cylinders. Under cyclic loading, if this $ au_{max}$ is too high for the soft core material, it leads to repeated plastic deformation at that depth, initiating fatigue micro-cracks. These cracks then propagate under further loading, potentially leading to spalling (pitting) of the tooth surface. If such fatigue damage occurs during running-in, the subsequent surface hardening cannot restore the gear’s full life potential. Therefore, load must be strictly controlled, and the tooth surfaces must be frequently inspected. Running-in should stop once an optimal contact pattern is achieved.

Post-running-in, the gear teeth require final inspection and touch-up. A phenomenon sometimes observed is mild adhesive wear (scuffing) on the tips of a few teeth. This is due to the relatively soft surfaces and initial roughness causing localized heating and microwelding. Controlling lubricant temperature and using a higher viscosity oil during running-in can mitigate this risk.

IV. The Core Strategy: Surface Hardening of Herringbone Gear Teeth

The predominant failure mode for industrial herringbone gears is contact fatigue manifested as surface pitting and spalling. To prevent this, the maximum orthogonal shear stress $ au_{max}$ generated below the contact surface must be less than or equal to the material’s allowable fatigue limit at that location. This allowable stress is primarily a function of hardness. Surface hardening is the targeted solution: it creates a shallow, high-hardness case with superior strength, wear resistance, and, critically, beneficial compressive residual stresses. These compressive stresses counteract the applied tensile components of the contact stress field, dramatically raising the fatigue threshold. Meanwhile, the tough, high-strength core prevents catastrophic tooth breakage.

For the hardening to be effective, the case depth and hardness must be rationally determined based on the service load. The case must be deep enough to encompass the depth of the maximum shear stress $z_0$. Its hardness must be sufficient to withstand the magnitude of $ au_{max}$.

4.1 Determining Required Case Depth and Hardness

This is an engineering calculation based on operational parameters. Let’s consider an example based on common rolling mill data.

Step 1: Calculate the maximum contact shear stress $ au_{max}$ and its depth $z_0$.

Based on Hertzian theory for two contacting cylinders (approximating gear teeth contact near the pitch line), the shear stress $ au_{zx}$ along the z-axis (depth) is given by:

$$ au_{zx} = p_0 \frac{x}{a} \left[ 1 + \left( \frac{z}{a} ight)^2 ight]^{-1}$$

where $p_0$ is the maximum contact pressure and $a$ is the half-width of the contact ellipse. The maximum value of this shear stress, $ au_{max}$, and its location $z_0$ are found by differentiation:

$$ au_{max} \approx 0.3 p_0 \quad ext{at a depth} \quad z_0 \approx 0.78 a$$

The half-width $a$ and pressure $p_0$ are calculated from the load, geometry, and material properties:

$$a = \sqrt{\frac{4PR}{ \pi b E’}}, \quad p_0 = \sqrt{\frac{PE’}{\pi b R}}$$

with

$$\frac{1}{E’} = \frac{1- u_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1- u_2^2}{E_2}, \quad \frac{1}{R} = \frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2}$$

Where $P$ is the load per unit face width $b$, $R_1, R_2$ are effective radii of curvature, $E$ is Young’s modulus, and $ u$ is Poisson’s ratio.

For a typical heavy-duty herringbone gear in a rolling mill, calculations might yield values like:

$$ au_{max} \approx 45 ext{ kgf/mm}^2, \quad z_0 \approx 1.2 ext{ mm}$$

Industry practice suggests a safety factor where the allowable shear stress $[ au]$ is about 50-55% of the material’s shear yield strength $ au_s$. The shear yield strength relates to Vickers hardness ($HV$) approximately by $ au_s \approx HV / 3$ (in kgf/mm² units). Therefore, the required case hardness $HV_{case}$ must satisfy:

$$ au_{max} \leq [ au] = 0.55 au_s \approx 0.55 imes \frac{HV_{case}}{3}$$

$$\Rightarrow HV_{case} \geq \frac{3 imes au_{max}}{0.55} \approx \frac{3 imes 45}{0.55} \approx 245 ext{ kgf/mm}^2$$

This converts to approximately 55-56 HRC. For high reliability, a final case hardness target of 56-58 HRC is specified.

Step 2: Determine Case Depth.

To ensure the dangerous stress region $z_0$ is well within the strengthened layer and away from the brittle case-core interface, the total effective case depth is typically set to 1.5 to 2 times $z_0$. Considering $z_0 \approx 1.2$ mm and observed spalling depths, a final case depth of 2.0 – 2.5 mm is determined.

4.2 Residual Stress Distribution and Influencing Factors

Surface hardening induces a complex residual stress state due to thermal and transformation stresses. The final distribution is a superposition of:

– Thermal Stress: Surface cooling contraction constrained by the hot core leads to final tensile stress at the surface and compression in the core.

– Transformation Stress: Martensite formation at the surface (volume expansion) constrained by the core leads to final compressive stress at the surface and tension in the core.

The net result in a successful surface hardening is a surface in compression, a subsurface peak of tensile stress in the transition zone, and a core returning to near-zero or mild tension/compression. This surface compression is highly beneficial for contact fatigue resistance.

Key factors influencing this favorable profile for herringbone gears include:

- Carbon Content: Higher carbon increases martensite volume expansion, amplifying surface compressive stresses.

- Case Depth: An optimal ratio of case depth to component size exists. Too shallow a case places the dangerous tensile peak too close to the surface. Too deep a case can reduce surface compression. A case depth of 10-20% of the tooth thickness is often effective.

- Hardness Gradient (Transition Zone Width): A very sharp hardness drop at the case-core interface concentrates tensile stress. A wider, more gradual transition (width ~25-30% of case depth) lowers and shifts the tensile peak inward, improving performance.

- Tempering: Low-temperature tempering (150-200°C) slightly reduces hardness but relieves peak stresses and reduces brittleness without significantly compromising the beneficial compression. “Self-tempering” using residual heat can be equally effective.

- Hardened Pattern: For herringbone gear teeth, the hardening should cover the entire active flank and root fillet to avoid stress concentrations at the pattern edge. The boundary should be placed strategically, e.g., keeping it at least 3-5 mm away from the critical root fillet.

- Grinding: Post-hardening grinding should be minimized or avoided. Removing more than 10-15% of the case depth can eliminate the beneficial compressive layer or even induce detrimental tensile stresses at the new surface.

- Total Acetylene Consumption ($V_{C_2H_2}$): Determined from required depth and travel speed.

$$V_{C_2H_2} = k \cdot v \cdot B \cdot q$$

Where $v$ is travel speed (cm/min), $B$ is effective nozzle width (cm), $q$ is specific acetylene consumption (l/cm²·h), and $k$ is a factor (~1.1). For a 2.5 mm depth, reference tables give $v \approx 10$ cm/min and $q \approx 120$ l/cm²·h. With $B=7$ cm:

$$V_{C_2H_2} \approx 1.1 imes 10 imes 7 imes 120 \approx 9240 \ ext{ l/h}$$ - Flame Power Intensity: $q \approx 120 \ ext{ l/cm²·h}$ (as selected).

- Total Oxygen Consumption: Typically 1.1 – 1.2 times acetylene flow.

$$V_{O_2} \approx 1.15 imes 9240 \approx 10600 \ ext{ l/h}$$ - Nozzle Design: A multi-orifice “comb” nozzle is used. For the calculated flow, a nozzle with a mixing chamber diameter of 4 mm, injector orifice of 2 mm, and approximately 40-45 burner orifices of 0.7 mm diameter is suitable. The nozzle-to-surface distance is maintained at ~15 mm.

- Temperature Control: Heating temperature is in the range of 850-900°C (austenitizing). “Self-tempering” is controlled by monitoring the post-quench surface temper color, aiming for a temperature of 200-250°C, which corresponds to the desired low-temperature temper.

- Gas Pressure: Acetylene pressure is maintained at 0.5 – 0.7 bar; Oxygen pressure at 3 – 4 bar.

V. Practical Application: Flame Hardening of Herringbone Gear Teeth

For large herringbone gears where induction hardening equipment may be limiting, controlled flame hardening is a viable and effective method. The principles are identical to induction hardening, differing only in the heat source. The process for a single herringbone gear tooth flank involves progressive, continuous heating with a multi-orifice flame head followed by immediate quench spray.

Based on the earlier determination (Case depth: 2.0-2.5 mm, Hardness: 56-58 HRC), the flame hardening parameters are engineered as follows:

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Effective Case Depth | 2.0 – 2.5 mm |

| Surface Hardness | 56 – 58 HRC |

| Hardened Width (on flank) | ~70 mm (Full profile height) |

| Distance from boundary to root fillet | ≥ 5 mm |

Parameter Calculation and Selection:

Each tooth flank of the herringbone gear is hardened in a single, continuous pass without overlap at the tooth center to prevent soft spots or re-tempered zones. This meticulous process ensures the hardened layer on the herringbone gear teeth meets the exacting specifications required to resist contact fatigue and drastically extend service life.

Conclusion

Extending the life of herringbone gears in demanding rolling mill applications is a systems engineering challenge. It requires an integrated approach starting with high-purity, properly forged alloy steel. A rigorous quenching and tempering treatment establishes a strong and tough core. A carefully controlled running-in process perfects the gear mesh without inducing subsurface damage. Finally, a surface hardening process—whose depth and hardness are scientifically determined from operational stress calculations—is precisely applied to create a wear-resistant surface layer imbued with beneficial compressive stresses. Flame hardening, with its calculated parameters for heat input and pattern control, is a practical and effective method for applying this final, life-extending treatment to large herringbone gears. By mastering each link in this chain, the operational lifespan of these critical components can be significantly enhanced, reducing downtime and improving mill productivity.