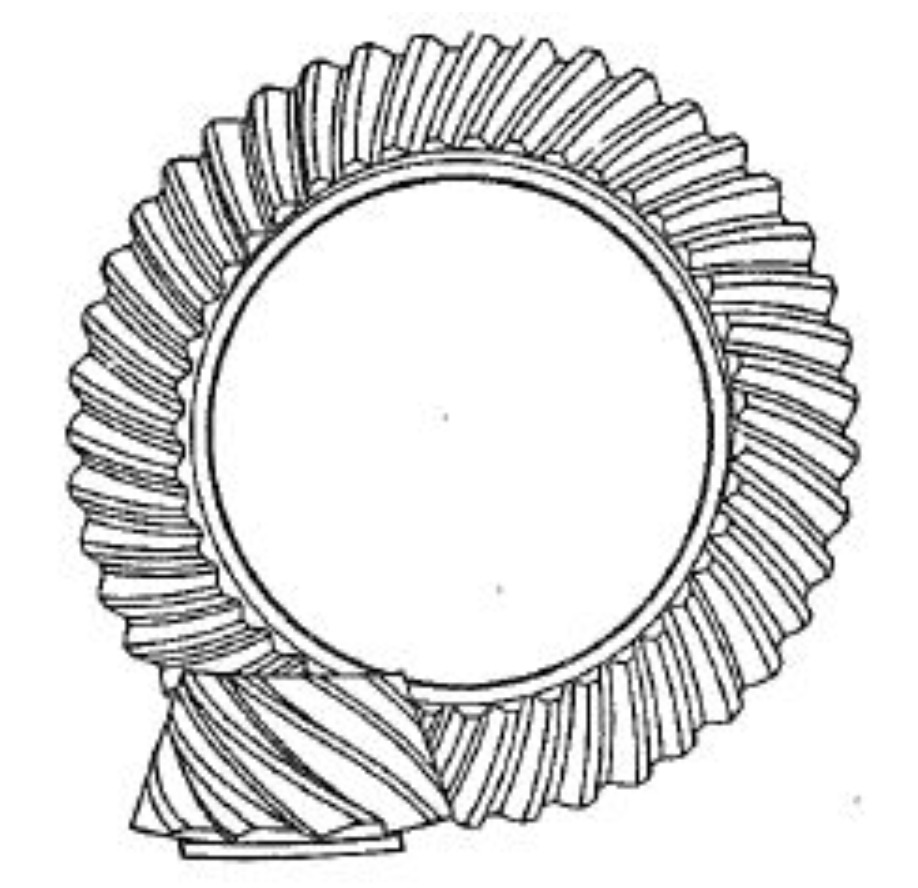

In the field of precision transmission systems, hypoid gears have emerged as a critical component due to their ability to transmit power between non-parallel shafts with high efficiency and compact design. Following harmonic drives and RV reducers, hypoid gear reducers represent a novel transmission form for robotic applications, offering advantages such as high stiffness, high precision, and lightweight properties. However, conventional hypoid gears used in automotive or helicopter applications typically feature low reduction ratios and limited transmission accuracy, which are insufficient for the demanding requirements of industrial robots. High reduction ratio hypoid gears, characterized by their compact spatial footprint, large reduction ratios, lightweight transmission, and strong load-bearing capacity, present a viable solution. Despite these benefits, the complex topological structure of hypoid gear tooth surfaces, especially in high reduction ratio configurations, poses significant challenges in manufacturing, numerical simulation, and tooth surface modification. This paper addresses these challenges by proposing an active tooth surface design methodology that emphasizes large inclination of contact paths to enhance comprehensive transmission performance.

The design and optimization of hypoid gears involve intricate geometrical and mechanical considerations. Traditional design methods often rely on trial-and-error approaches, which are time-consuming and may not yield optimal performance. Active tooth surface design technology, however, allows for the proactive control of tooth surface geometry based on functional requirements, enabling precise manipulation of meshing performance. In this study, we focus on hypoid gears with a high reduction ratio, specifically a gear pair with a pinion-to-gear ratio of 5:75. The primary objective is to investigate the influence of contact path length on various performance parameters, such as transmission error, load distribution, root bending stress, and surface flash temperature, under conditions of large contact path inclination. By preset ting multiple tooth surface imprints with varying degrees of contact line inclination and specified contact ellipse parameters, we aim to derive a modified tooth surface that exhibits superior performance compared to the original design.

The foundation of hypoid gear design lies in the mathematical representation of the tooth surface. For the pinion, the cutting surface of the cutter head can be described in the cutter coordinate system $S_f (O_f X_f Y_f Z_f)$. The position vector $\mathbf{r}_f$ and unit normal vector $\mathbf{n}_f$ of the cutter surface are given by:

$$\mathbf{r}_f (s_p, \theta_p) = \begin{bmatrix} (r_p + s_p \sin \alpha_1) \cos \theta_p \\ (r_p + s_p \sin \alpha_1) \sin \theta_p \\ -s_p \cos \alpha_1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix},$$

$$\mathbf{n}_f (\theta_p) = \begin{bmatrix} -\cos \alpha_1 \cos \theta_p \\ -\cos \alpha_1 \sin \theta_p \\ -\sin \alpha_1 \end{bmatrix},$$

where $r_p$ is the tip radius of the cutter, $s_p$ is the shift distance in the tip direction, $\alpha_1$ is the pressure angle of the pinion cutter’s outer blade, and $\theta_p$ is the rotation angle of the cutter. To accurately model the pinion generation process, a series of coordinate transformations are employed, linking the machine coordinate system $S_{E0}$, the cradle coordinate system $S_p$, the cutter rotation coordinate system $S_t$, the cutter coordinate system $S_f$, and the pinion coordinate system $S_1$. The position vector $\mathbf{r}_1$ and unit normal vector $\mathbf{n}_1$ of the pinion tooth surface in $S_1$ are derived through transformation matrices:

$$\mathbf{r}_1 = \mathbf{M}_{1b} \mathbf{M}_{bE2} \mathbf{M}_{E2E0} \mathbf{M}_{E0E1} \mathbf{M}_{E1t} \mathbf{M}_{tf} \mathbf{r}_f,$$

$$\mathbf{n}_1 = \mathbf{L}_{1b} \mathbf{L}_{bE2} \mathbf{L}_{E2E0} \mathbf{L}_{E0E1} \mathbf{L}_{E1t} \mathbf{L}_{tf} \mathbf{n}_f,$$

where $\mathbf{M}$ and $\mathbf{L}$ represent the 4×4 position transformation matrices and 3×3 rotation matrices, respectively. The meshing equation during the cutting process ensures contact between the cutter surface and the pinion tooth surface:

$$f(s_p, \theta_p, \phi_1) = \mathbf{n}_1 \cdot \mathbf{v} = \mathbf{n}_1 \cdot \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}_1}{\partial \phi_1} = 0,$$

where $\phi_1$ is the rotation angle of the pinion during processing. Similarly, the gear tooth surface can be derived by adjusting the corresponding parameters.

The conjugate tooth surface of the pinion is obtained by considering the meshing relationship between the pinion and gear. Using coordinate systems $S_1$ for the pinion and $S_2$ for the gear, with an axis angle of 90° and an offset distance $E$, the position vector $\mathbf{r}_{n1}$ and unit normal vector $\mathbf{n}_{n1}$ at the reference point in the stationary coordinate system $S_{n1}$ are calculated as:

$$\mathbf{r}_{n1}(\psi_2) = \mathbf{M}_{n1n2} \mathbf{M}_{n22}(\psi_2) \mathbf{r}_2,$$

$$\mathbf{n}_{n1}(\psi_2) = \mathbf{L}_{n1n2} \mathbf{L}_{n22}(\psi_2) \mathbf{n}_2,$$

where $\psi_2$ is the initial rotation angle of the gear. The relative velocity $\mathbf{v}_{n1}(\psi_2)$ is determined, and the meshing equation at the reference point is satisfied:

$$\mathbf{n}_{n1} \cdot \mathbf{v}_{n1} = 0.$$

Solving this equation yields $\psi_2$, and the conjugate pinion surface vectors $\mathbf{r}_c$ and $\mathbf{n}_c$ in $S_1$ are obtained through transformation.

Active tooth surface design involves modifying the conjugate pinion surface to introduce a parabolic ease-off topology. This modification transforms the theoretical line contact into point contact, reducing sensitivity to misalignment and load-induced deformations. The ease-off parabola along the meshing direction is defined as:

$$y = -\frac{\delta}{a^2} x^2, \quad x \in (-a, a),$$

where $a$ is the preset semi-major axis length of the contact ellipse, $\delta$ is the deformation amount (typically 0.00635 mm), the x-axis direction aligns with the contact ellipse major axis, and the y-axis direction is the tooth surface normal. Outside the contact zone, a different parabola is used to remove excess material:

$$y = -\frac{\sigma}{a^2} x^2 + \sigma, \quad x \in (-\infty, -a) \cup (a, +\infty),$$

where $\sigma$ is an adjustment parameter. The normal modification amount $\delta_y$ combines both regions. The modified tooth surface $\Sigma_t$ is discretized, and the position vector $\mathbf{r}_{t,M}$ and unit normal vector $\mathbf{n}_{t,M}$ at any point $M$ are:

$$\mathbf{r}_{t,M} = \mathbf{r}_{c,M} + \delta_{y,M} \mathbf{n}_{c,M},$$

$$\mathbf{n}_{t,M} = \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}_{t,M}}{\partial \theta_p} \times \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}_{t,M}}{\partial s_p} \left/ \left| \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}_{t,M}}{\partial \theta_p} \times \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}_{t,M}}{\partial s_p} \right| \right. .$$

The normal deviation $\Delta \delta_M$ between the conjugate and modified surfaces at point $M$ is:

$$\Delta \delta_M = (\mathbf{r}_{t,M} – \mathbf{r}_{c,M}) \cdot \mathbf{n}_{c,M}.$$

The differential form of $\Delta \delta_M$ is expressed as:

$$\Delta \delta_M = – \left( \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}_c}{\partial \phi_1} \delta \phi_1 + \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}_c}{\partial \phi_2} \delta \phi_2 + \cdots + \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}_c}{\partial \phi_k} \delta \phi_k \right) \cdot \mathbf{n}_c,$$

where $\phi_j$ ($j=1,2,\ldots,k$) are the machining parameters. Since $\mathbf{n}_c$ is perpendicular to $\partial \mathbf{r}_c / \partial s_p$ and $\partial \mathbf{r}_c / \partial \theta_p$, the equation simplifies to:

$$\Delta \delta_M = – \left( \frac{\partial (\mathbf{r}_c \cdot \mathbf{n}_c)}{\partial \phi_1} \delta \phi_1 + \frac{\partial (\mathbf{r}_c \cdot \mathbf{n}_c)}{\partial \phi_2} \delta \phi_2 + \cdots + \frac{\partial (\mathbf{r}_c \cdot \mathbf{n}_c)}{\partial \phi_k} \delta \phi_k \right).$$

For $n$ grid nodes, this leads to a system of equations:

$$\begin{bmatrix} \Delta \delta_1 \\ \Delta \delta_2 \\ \vdots \\ \Delta \delta_n \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial (\mathbf{r}_{c1} \cdot \mathbf{n}_{c1})}{\partial \phi_1} & \frac{\partial (\mathbf{r}_{c1} \cdot \mathbf{n}_{c1})}{\partial \phi_2} & \cdots & \frac{\partial (\mathbf{r}_{c1} \cdot \mathbf{n}_{c1})}{\partial \phi_k} \\ \frac{\partial (\mathbf{r}_{c2} \cdot \mathbf{n}_{c2})}{\partial \phi_1} & \frac{\partial (\mathbf{r}_{c2} \cdot \mathbf{n}_{c2})}{\partial \phi_2} & \cdots & \frac{\partial (\mathbf{r}_{c2} \cdot \mathbf{n}_{c2})}{\partial \phi_k} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \frac{\partial (\mathbf{r}_{cn} \cdot \mathbf{n}_{cn})}{\partial \phi_1} & \frac{\partial (\mathbf{r}_{cn} \cdot \mathbf{n}_{cn})}{\partial \phi_2} & \cdots & \frac{\partial (\mathbf{r}_{cn} \cdot \mathbf{n}_{cn})}{\partial \phi_k} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \Delta \phi_1 \\ \Delta \phi_2 \\ \vdots \\ \Delta \phi_k \end{bmatrix},$$

or in matrix form $\Delta \boldsymbol{\delta} = \boldsymbol{\Omega} \Delta \boldsymbol{\phi}$. The least squares method is applied to solve for the optimal machining parameter adjustments:

$$\Delta \boldsymbol{\phi} = (\boldsymbol{\Omega}^T \boldsymbol{\Omega})^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Omega}^T \Delta \boldsymbol{\delta}.$$

This iterative process adjusts the pinion machining parameters to minimize the normal deviation between the pinion surface and the modified surface.

To evaluate the performance of the modified hypoid gear, several key parameters are analyzed. The amplitude of loaded transmission error (ALTE) is calculated from the relative normal displacement over a meshing cycle:

$$\text{ALTE} = \frac{180}{\pi} \Delta Y_n (\mathbf{r}’_2 \times \mathbf{e}’_2 \cdot \mathbf{n}’_2),$$

where $\Delta Y_n$ is the difference between the maximum and minimum normal displacements, $\mathbf{r}’_2$ is the position vector of the gear concave surface, $\mathbf{e}’_2$ is the unit normal vector, and $\mathbf{n}’_2$ is the unit vector along the gear axis. The contact stress $\sigma_m$ is computed using:

$$\sigma_m = Z_{MB} Z_H Z_E Z_{LS} Z_\beta Z_K \sqrt{ \frac{F_{mt} (i_v + 1)}{d_{v1} l_b i_v} },$$

where $d_{v1}$ is the equivalent pitch diameter of the pinion, $l_b$ is the contact path length, $i_v$ is the gear ratio, $F_{mt}$ is the tangential force, and $Z$ coefficients account for various factors such as mesh stiffness, elasticity, and load distribution. The root bending stress $\sigma_g$ is derived based on Saint-Venant’s principle and stress superposition, relating to the contact stress as $\sigma_h \propto \sigma_g$. The surface flash temperature $\theta$, critical for assessing scuffing resistance, is given by the Block flash temperature formula:

$$\theta = 1.11 \mu_i X_j X_s \frac{w_b}{\sqrt{2b}} \frac{ |v_{t1} – v_{t2}| }{ B_{M1} \sqrt{v_{t1}} + B_{M2} \sqrt{v_{t2}} },$$

where $\mu_i$ is the average friction coefficient under mixed elastohydrodynamic lubrication, $X_j$ and $X_s$ are the engagement and load distribution coefficients (set to 1.0), $w_b$ is the unit load, $b$ is the contact ellipse semi-minor axis, $v_{t1}$ and $v_{t2}$ are the tangential velocities of the pinion and gear, and $B_{M1}$ and $B_{M2}$ are thermal contact coefficients. The average friction coefficient $\mu_i$ is expressed as:

$$\mu_i = \mu_b (1 – \varepsilon) + \mu_m \varepsilon^{0.2},$$

where $\mu_b$ is the boundary lubrication friction coefficient (0.11), $\mu_m$ is the full elastohydrodynamic lubrication friction coefficient, and $\varepsilon$ is the ratio of minimum oil film thickness to composite surface roughness. The relationship between flash temperature and contact stress is $\theta \propto \sigma_h$, indicating that longer contact paths reduce flash temperature.

In our case study, we consider a hypoid gear pair with a pinion-to-gear ratio of 5:75. The geometric parameters of the gear pair are summarized in Table 1.

| Parameter | Gear | Pinion |

|---|---|---|

| Shaft Angle (°) | 90 | 90 |

| Offset Distance (mm) | 27 | 27 |

| Number of Teeth | 75 | 5 |

| Mid-Point Cone Distance (mm) | 69.862 | 51.930 |

| Pitch Cone Angle (°) | 74.15 | 14.10 |

| Face Cone Angle (°) | 81.978 | 7.960 |

| Root Cone Angle (°) | 81.221 | 6.852 |

| Spiral Angle (°) | 27.269 | 50.110 |

| Addendum (mm) | 0.275 | 2.712 |

| Dedendum (mm) | 9.510 | 0.769 |

| Face Width (mm) | 11.200 | 13.892 |

The pinion’s rated input speed is 2000 rpm, and the thermal contact coefficients for both gears are 14 N/(mm·°C·s^{0.5}). The lubricant has an environmental viscosity of 0.02 Pa·s, a pressure-viscosity coefficient of 11.4 GPa^{-1}, and a composite surface roughness of 0.35 µm. We preset multiple tooth surface imprints with varying contact path lengths and inclination degrees. For instance, two contrasting tooth surfaces, designated as I and II, are designed with different contact path lengths and ellipse parameters. Surface I has a contact path length of 6.832 mm and a semi-major axis of 2.423 mm, while Surface II has a contact path length of 7.191 mm and a semi-major axis of 2.372 mm. Performance comparisons, as shown in Table 2, indicate that Surface II exhibits lower transmission error, root bending stress, and flash temperature, despite a smaller contact area, highlighting the significance of contact path length.

| Tooth Surface | Contact Path Length (mm) | Semi-Major Axis (mm) | Contact Area (mm²) | Transmission Error (µrad) | Max Root Bending Stress (N/mm²) | Max Flash Temperature (°C) | ALTE (µrad) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 6.832 | 2.423 | 8.961 | 122.45 | 783.2 | 149.8 | 929 |

| II | 7.191 | 2.372 | 7.098 | 84.86 | 671.6 | 140.1 | 901 |

We further investigate the effect of contact path length by varying it from an initial state of 5.726 mm to a final state of 9.662 mm, with a fixed semi-major axis of 2.425 mm. The transmission error decreases from 126.50 µrad to 29.04 µrad, a reduction of 77.0%, as the contact path length increases. Under different load conditions (200, 300, and 400 N·m), the ALTE, maximum flash temperature, and root bending stress are analyzed. The results, summarized in Table 3, show that longer contact paths lead to significant improvements in all performance metrics.

| Load (N·m) | Performance Parameter | Initial State (5.726 mm) | Final State (9.662 mm) | Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 | ALTE (µrad) | ~180 | ~135 | 24.9 |

| Max Flash Temperature (°C) | ~150 | ~110 | 26.3 | |

| Max Root Bending Stress (N/mm²) | ~1100 | ~790 | 28.1 | |

| 300 | ALTE (µrad) | ~220 | ~175 | 20.3 |

| Max Flash Temperature (°C) | ~180 | ~139 | 22.9 | |

| Max Root Bending Stress (N/mm²) | ~1300 | ~1000 | 23.2 | |

| 400 | ALTE (µrad) | ~260 | ~215 | 17.2 |

| Max Flash Temperature (°C) | ~210 | ~160 | 23.9 | |

| Max Root Bending Stress (N/mm²) | ~1500 | ~1150 | 23.3 |

Based on these findings, a target tooth surface is designed with a large inclination, featuring a contact path length of 9.451 mm and a semi-major axis of 2.212 mm. The machining parameters for the original and target tooth surfaces are listed in Table 4.

| Machining Parameter | Original Tooth Surface | Target Tooth Surface |

|---|---|---|

| Cutter Rotation Angle (°) | 315.32 | 296.90 |

| Cutter Tilt Angle (°) | 12.63 | 8.72 |

| Radial Setting (mm) | 62.611 | 63.921 |

| Angular Setting (°) | 62.140 | 86.630 |

| Machine Center to Back (mm) | 9.891 | 8.016 |

| Axial Setting (mm) | 0.691 | 0.718 |

| Installation Angle (°) | 351.88 | 356.25 |

| Tip Radius (mm) | 0.51 | 1.32 |

| Ratio of Roll | 15.165 | 15.384 |

Tooth contact analysis (TCA) reveals that the target tooth surface exhibits a contact pattern centered closer to the tooth surface midpoint, with a nearly straight and highly inclined contact path, resulting in diagonal contact that nearly spans the entire face width. The contact area is larger than that of the original tooth surface. The transmission error curves for both surfaces are similar in peak value, but the ease-off topology shows that the target surface has material removed at the toe and added at the heel, with minimal overall deviation. Loaded tooth contact analysis (LTCA) under loads of 100, 200, and 400 N·m demonstrates that the original tooth surface experiences high contact stress concentration at the tooth tip, increasing with load and posing a risk of edge contact. In contrast, the target tooth surface distributes contact stress more evenly across the central region, with lower overall stress levels and reduced edge contact risk. The ALTE for the original and target surfaces are 965 µrad and 925 µrad, respectively, indicating smoother meshing and reduced vibration. The root bending stress analysis shows that the target surface has a maximum stress of 971.3 N/mm² at the 21st meshing position, compared to 1104.4 N/mm² at the 18th position for the original surface, a reduction of 12.0%. Flash temperature analysis reveals that the target surface has a peak temperature of 139.5°C, 6.3% lower than the original surface’s 148.9°C, and a more uniform temperature distribution due to improved lubrication conditions from larger modifications at the engagement and disengagement ends.

In conclusion, the active tooth surface design methodology for high reduction ratio hypoid gears, emphasizing large inclination of contact paths, significantly enhances comprehensive transmission performance. By presetting contact path length and ellipse parameters, and employing parabolic ease-off modification, we achieve a tooth surface with reduced transmission error, lower root bending stress, improved load distribution, and enhanced scuffing resistance. The results demonstrate that longer contact paths, under conditions of high inclination, lead to better performance across multiple metrics. This approach provides a robust framework for optimizing hypoid gears in high-precision applications, such as robotic systems, where reliability and efficiency are paramount. Future work could explore the integration of dynamic analysis and real-world validation to further refine the design process.