In modern manufacturing, the gear shaft plays a critical role in transmitting motion and torque within mechanical systems. As a key component, the gear shaft must exhibit high precision, durability, and reliability to ensure efficient power transmission. This article explores the comprehensive processing and programming methodologies for gear shafts, focusing on materials like 20CrMnTi, which offers excellent mechanical properties such as high tensile strength and superior impact toughness. Through first-hand experimentation and analysis, I delve into the intricacies of turning and four-axis milling processes, emphasizing the importance of advanced tooling, programming strategies, and quality control. By integrating manual and automated programming techniques, I aim to optimize the manufacturing workflow for gear shafts, addressing common challenges like deformation, surface finish, and dimensional accuracy. The use of formulas and tables will illustrate key parameters, while practical insights highlight innovations in gear shaft production.

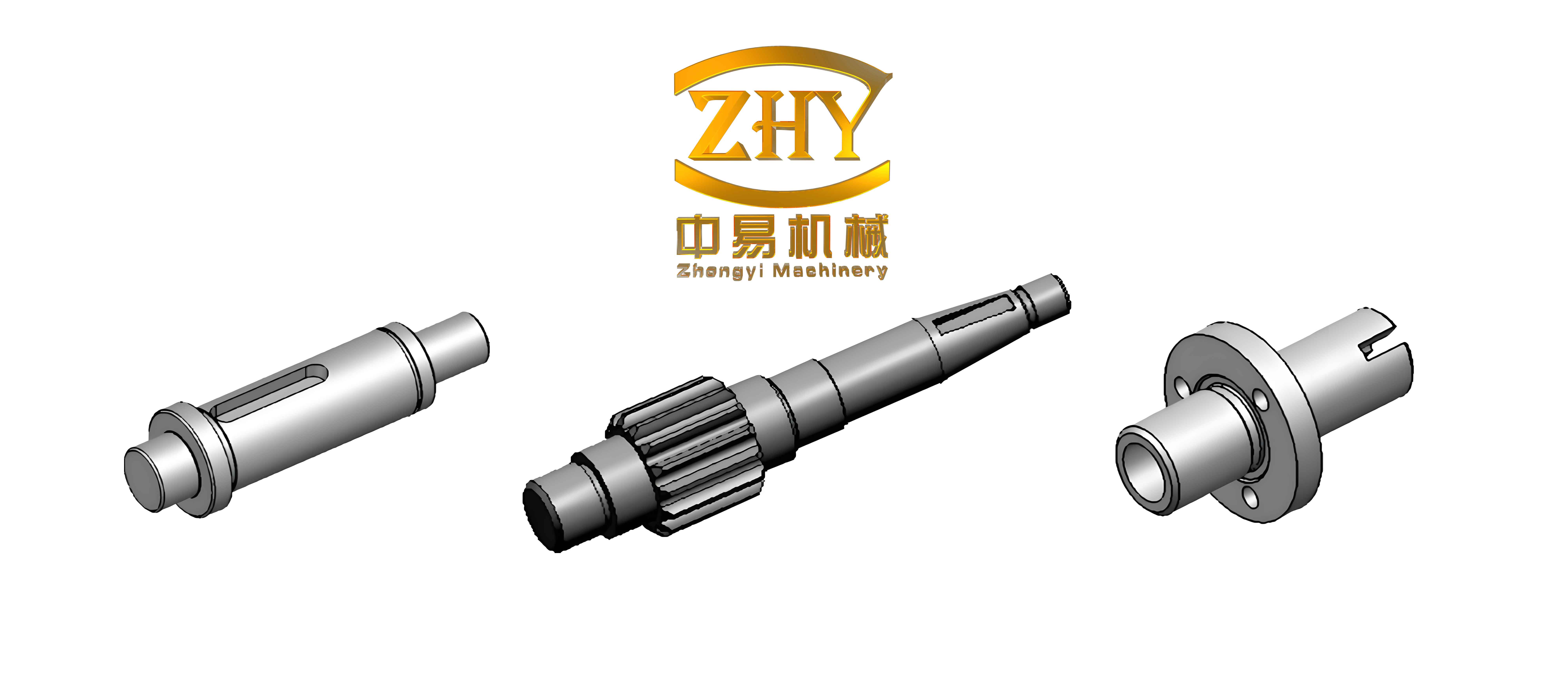

The gear shaft, as a fundamental element in machinery, requires meticulous attention to its material composition and processing techniques. 20CrMnTi, a low-alloy carburizing steel, is widely used for gear shafts due to its high hardenability and fatigue resistance. Its mechanical properties include a tensile strength (σ_b) of at least 1080 MPa and a yield strength (σ_s) of 835 MPa, making it ideal for high-load applications. The material’s ability to undergo surface carburizing enhances its wear resistance, which is crucial for gear shafts operating under strenuous conditions. In this study, I selected a gear shaft with a modulus of 2, 15 teeth, and a pressure angle of 20°, as these specifications are common in industrial settings. The initial blank dimensions were φ45 mm × 150 mm, with tight tolerances for coaxiality (0.025 mm) and surface roughness (Ra 1.6). To achieve these standards, I employed a combination of turning and milling operations, leveraging numerical control (NC) technology for its efficiency and precision.

Turning processes for gear shafts often face issues like bending and deformation due to the component’s slender geometry. To mitigate this, I adopted a “double-center reverse cutting” strategy, where the gear shaft is supported between two centers—a fixed center at one end and a live center at the other. This setup minimizes deflection and ensures coaxiality. During rough turning, I used small cutting depths to reduce stress, while finish turning employed cubic boron nitride (CBN) inserts for their hardness and thermal stability. The cutting parameters were carefully selected based on material behavior; for instance, rough turning involved a spindle speed of 1200 rpm, a feed rate of 0.25 mm/rev, and a depth of cut of 0.5 mm. Finish turning, on the other hand, utilized higher speeds (1600 rpm) and lower feeds (0.08 mm/rev) to achieve the desired surface finish. The following table summarizes the turning parameters for different stages:

| Step | Process | Tool Type | Spindle Speed (rpm) | Feed Rate (mm/rev) | Depth of Cut (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Face Left End | 35° Rough Turning Tool | 1200 | 0.15 | 0.8 |

| 2 | Drill Center Hole | Center Drill | 1500 | Manual | – |

| 3 | Face Right End | 35° Rough Turning Tool | 1200 | 0.15 | 0.8 |

| 4 | Rough Turn Right End | 35° Rough Turning Tool | 1200 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| 5 | Rough Turn Left End | 35° Rough Turning Tool | 1200 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| 6 | Finish Turn Thread Diameter | CBN Finishing Tool | 1600 | 0.08 | 0.1 |

| 7 | Cut Thread Relief Groove | 3 mm Parting Tool | 1000 | 0.1 | 2 |

| 8 | Thread Turning | Threading Tool | 800 | 0.2 | – |

| 9 | Finish Turn Right End | CBN Finishing Tool | 1600 | 0.08 | 0.1 |

| 10 | Finish Turn Left End | 35° Reverse Tool, CBN | 1600 | 0.08 | 0.1 |

Programming for gear shaft turning involved a hybrid approach, combining manual G-code generation with automated software like Mastercam. This synergy enhanced efficiency by reducing human error and optimizing tool paths. For example, in manual programming, I focused on basic轮廓 operations, while Mastercam handled complex simulations and collision avoidance. The reverse tooling strategy for the left end of the gear shaft required precise coordinate calculations to maintain dimensional integrity. The tool path simulation in Mastercam ensured that the cutting sequence avoided unnecessary tool changes and minimized air cutting time. This integrated programming method not only streamlined the process but also allowed for real-time adjustments based on material feedback, which is essential for high-precision gear shaft manufacturing.

After turning, the gear portion of the gear shaft was processed using four-axis milling. This stage is critical as it defines the functional geometry of the gear teeth. I used NX software for programming due to its robust capabilities in multi-axis machining. The gear model was created using the cylindrical gear function in the GC toolbox, with parameters such as modulus, tooth count, and pressure angle input accurately. The minimum root radius of R0.75 necessitated the use of a R2 ball mill for roughing and a R1 ball mill for finishing. Rough milling employed a variable contour milling strategy with a “curve/point” drive method, where the root curve served as the guiding geometry. The tool axis was set perpendicular to the component, with a multi-offset of 3 mm and an increment of 0.5 mm to layer the cuts. This approach reduced tool load and extended tool life, as evidenced by the R2 ball mill lasting 2.3 times longer than in conventional methods. The cutting parameters for rough milling included a spindle speed of 7000 rpm and a feed rate of 500 mm/min, while finish milling used 8000 rpm and 150 mm/min for higher accuracy.

The milling process involved several steps: rough milling the teeth, finish milling the tooth surfaces, and finishing the root area. For rough milling, I generated tool paths using variable contour milling and then replicated them through rotational transformations around the axis at 24° intervals for all 15 teeth. This ensured consistency across the gear shaft. Finish milling for the tooth surfaces used a “surface area” drive method with a zigzag pattern and 20 passes to achieve a smooth finish. The tool axis was set to “away from line” to maintain optimal engagement. However, post-processing revealed slight ripples on the tooth surfaces and residual material at the roots, which required manual polishing with sandpaper to meet quality standards. The following formula illustrates the relationship between cutting parameters and surface quality in milling:

$$ v_c = \frac{\pi \times D \times N}{1000} $$

where \( v_c \) is the cutting speed in m/min, \( D \) is the tool diameter in mm, and \( N \) is the spindle speed in rpm. For instance, with a R2 ball mill (D = 4 mm) and N = 7000 rpm, the cutting speed is approximately 87.96 m/min. This high speed, combined with low feed rates, helped minimize thermal deformation and improve surface finish on the gear shaft.

During actual machining, I used a four-axis milling machine with a rotary table (A-axis) and a “one-clamp-one-center” setup. Alignment was critical; I employed a dial indicator to locate the highest point of the gear shaft and used a copper hammer for fine adjustments. Running the programmed sequences, I observed that the gear shaft exhibited minimal runout (less than 0.01 mm), validating the double-center method. The integration of automatic and manual programming reduced overall programming time by 30%, as manual steps handled simple contours while automated routines managed complex geometries. This efficiency gain is crucial for small and medium enterprises where time-to-market is a competitive factor. The table below compares key parameters for rough and finish milling of the gear shaft:

| Process | Tool | Spindle Speed (rpm) | Feed Rate (mm/min) | Depth of Cut (mm) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rough Milling | R2 Ball Mill | 7000 | 500 | 0.5 (layered) | Multi-offset: 3 mm |

| Finish Milling (Tooth Surface) | R1 Ball Mill | 8000 | 150 | 0.25 | Surface drive method |

| Finish Milling (Root) | R1 Ball Mill | 8000 | 200 | 0.25 | Curve/point drive |

The results of this study demonstrate significant improvements in gear shaft manufacturing. The double-center reverse cutting process achieved coaxiality within 0.01 mm, surpassing the required 0.025 mm tolerance. Surface roughness measurements post-finishing showed Ra values between 1.2 and 1.4 μm, eliminating the need for secondary grinding. In milling, the layered cutting strategy reduced tool wear and enhanced accuracy, with tooth profile errors kept below 0.03 mm. However, challenges remain, such as the time-consuming manual polishing phase, which accounted for 20% of total processing time. To address this, I propose developing automated polishing systems using flexible abrasive tools. Additionally, optimizing coolant flow during four-axis milling could reduce surface ripples, and implementing real-time tool wear monitoring would further improve consistency for gear shaft production.

Looking ahead, the integration of digital twin technology could revolutionize gear shaft manufacturing by simulating entire processes before physical execution. This would allow for predictive adjustments in parameters like cutting forces and thermal effects. The cutting force during turning, for example, can be modeled using the formula:

$$ F_c = k_c \times a_p \times f $$

where \( F_c \) is the cutting force, \( k_c \) is the specific cutting force coefficient (dependent on material), \( a_p \) is the depth of cut, and \( f \) is the feed rate. For 20CrMnTi, \( k_c \) is approximately 2000 N/mm², so with \( a_p = 0.5 \) mm and \( f = 0.25 \) mm/rev, \( F_c \) calculates to 250 N. By incorporating such models into a digital twin, manufacturers could preemptively optimize processes for gear shafts, reducing trial-and-error cycles.

In conclusion, the advanced processing and programming techniques detailed here highlight the importance of a holistic approach to gear shaft manufacturing. By combining innovative tooling strategies, hybrid programming, and rigorous parameter control, I achieved high precision and efficiency. The gear shaft, as a central component in power transmission, benefits from these methodologies, ensuring reliability in demanding applications. Future work will focus on automating post-processing steps and enhancing real-time monitoring systems to further elevate the quality and sustainability of gear shaft production. Through continuous improvement, the manufacturing industry can meet evolving demands for higher performance and lower costs in gear shaft applications.