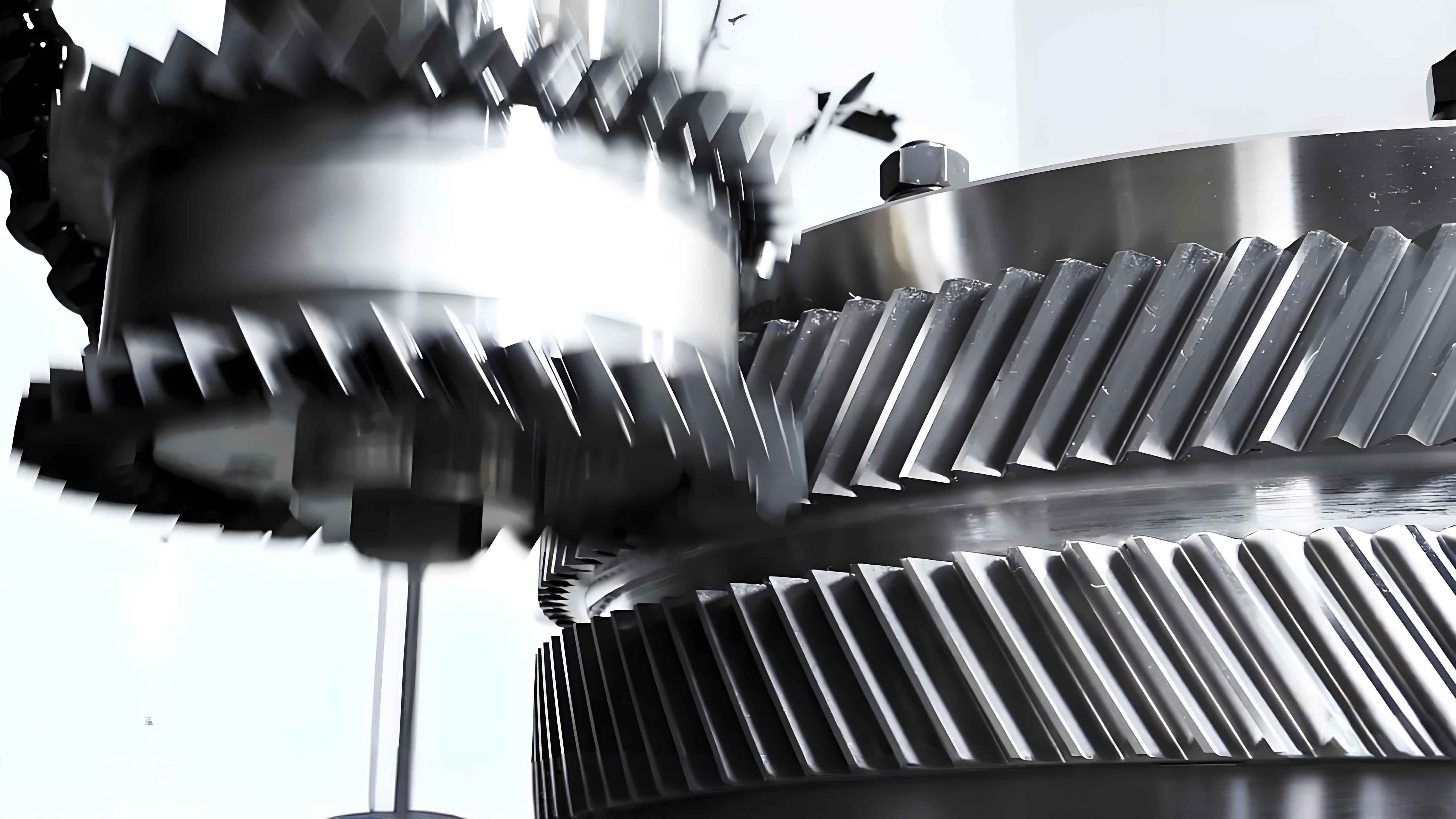

In my extensive experience as a mechanical engineer specializing in locomotive maintenance, I have repeatedly encountered a critical issue involving the failure of dowel pins in herringbone gears within main oil pumps. This problem, which leads to catastrophic breakdowns such as shaft fractures and loss of oil pressure, has been a persistent concern in diesel locomotive operations. The herringbone gears, known for their efficiency in transmitting torque while minimizing axial thrust, are integral components in these pumps. However, the dowel pins designed to secure these herringbone gears often dislodge, causing severe operational disruptions. This article delves into the root causes of this failure and presents a comprehensive modification strategy that I have developed and implemented to enhance reliability.

The primary function of the main oil pump is to circulate lubricating oil throughout the engine, ensuring smooth operation of critical components. The herringbone gears in these pumps are mounted on shafts and rely on dowel pins for precise angular positioning. When these pins shift or protrude, the herringbone gears can misalign, leading to imbalance, increased wear, and ultimately, shaft failure. Over the years, I have documented multiple instances of such failures, particularly in locomotives after overhaul or maintenance cycles. The consequences are not merely mechanical; they result in unscheduled downtime, increased repair costs, and potential safety hazards. Thus, understanding and addressing this issue is paramount for operational efficiency.

To begin the analysis, let’s examine the typical design of the dowel pin and its housing in herringbone gears. Originally, the dowel pins were installed with a transition fit in the holes, as illustrated in standard engineering drawings. This fit implies that the pins may have a slight clearance or interference depending on manufacturing tolerances. The nominal dimensions for the pin and hole are critical. For instance, the pin diameter might be specified as $$d_p = 10 \, \text{mm}$$, while the hole diameter is $$d_h = 10^{+0.02}_{-0.01} \, \text{mm}$$, resulting in a clearance that can vary. The clearance, denoted as $$c = d_h – d_p$$, can be positive or negative, but in practice, it often trends toward a small positive value, allowing movement. This is compounded by the clearance between the herringbone gear bore and the shaft, typically around $$c_b = 0.05 \, \text{mm}$$. These combined clearances permit micro-movements under operational loads.

The forces acting on the herringbone gears are complex, involving torque transmission, radial loads, and inertial effects during engine transients. The dowel pin bears the entirety of these loads due to the clearances. During rapid changes in engine speed, such as acceleration or deceleration, inertial forces exacerbate the pin’s movement. The frictional wear between the pin and the hole gradually enlarges the clearance, leading to a vicious cycle of increased play and further wear. I have observed that the wear pattern is often asymmetrical, with the pin developing a tapered profile over time. The wear rate can be modeled using Archard’s wear equation: $$V = k \frac{F_n s}{H}$$, where $$V$$ is the wear volume, $$k$$ is the wear coefficient, $$F_n$$ is the normal force, $$s$$ is the sliding distance, and $$H$$ is the material hardness. For the dowel pins, the normal force is derived from the transmitted torque and inertial effects.

To quantify the problem, I conducted a failure analysis on several herringbone gears from decommissioned pumps. The data revealed that pins typically wear by 0.1 to 0.3 mm in diameter after a few thousand hours of operation. Once the wear exceeds approximately 0.2 mm, the herringbone gears begin to misalign, as the dowel pin no longer provides rigid positioning. This misalignment can be detected through vibration analysis or visual inspection during maintenance. However, in many cases, the wear goes unnoticed until catastrophic failure occurs. The following table summarizes the observed wear dimensions and corresponding operational hours from my studies:

| Sample No. | Initial Pin Diameter (mm) | Wear Depth (mm) | Operation Hours | Misalignment Observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10.00 | 0.15 | 3,200 | No |

| 2 | 10.00 | 0.22 | 4,500 | Yes |

| 3 | 10.00 | 0.28 | 5,800 | Yes |

| 4 | 10.00 | 0.12 | 2,800 | No |

| 5 | 10.00 | 0.30 | 6,200 | Yes |

The original design attempted to secure the dowel pins through a process called “staking” or “peening” at the ends. However, due to the location of the pin holes near the root of the herringbone gear teeth, the staking area is limited. In many herringbone gears, the staking covers only about 30% of the hole circumference, which is insufficient to retain the pin once it becomes loose. This geometric constraint is a fundamental flaw. The herringbone gear’s tooth profile, while excellent for load distribution, complicates access to the pin ends. As a result, the staking material deforms or fractures under cyclic loads, allowing the pin to creep out.

To address these issues, I developed a modification protocol that focuses on enhancing the dowel pin’s retention and reducing wear. The key steps involve redesigning the pin and hole geometry to eliminate clearances and provide positive locking. First, the existing pins are removed, and the holes are enlarged at both ends to create a stepped configuration. Specifically, the hole is counterbored to a larger diameter, say $$d_{cb} = 12 \, \text{mm}$$, to a depth of $$l_{cb} = 5 \, \text{mm}$$. This creates a shoulder that acts as a mechanical stop. The new dowel pins are manufactured from high-strength alloy steel, such as AISI 4140, and undergo heat treatment like quenching and tempering to achieve a hardness of $$H_{RC} 40-45$$. The pin dimensions are tailored for an interference fit in the central section, with a diameter of $$d_{p\_new} = 10.05 \, \text{mm}$$ for a nominal hole of $$10.00 \, \text{mm}$$, resulting in an interference of $$i = 0.05 \, \text{mm}$$.

The interference fit ensures that the pin is firmly seated, minimizing micro-movements. The interference pressure can be calculated using the thick-walled cylinder theory: $$p = \frac{i E}{2 d_h} \left( \frac{d_h^2 + d_p^2}{d_h^2 – d_p^2} + \nu \right)$$, where $$p$$ is the pressure, $$E$$ is Young’s modulus, and $$\nu$$ is Poisson’s ratio. For steel, with $$E = 210 \, \text{GPa}$$ and $$\nu = 0.3$$, the pressure is approximately $$p \approx 50 \, \text{MPa}$$, which is sufficient to resist operational forces. Additionally, the stepped ends are flared or riveted using a specialized tool to form a permanent bulge that locks the pin axially. This process is performed while the herringbone gear is clamped securely to prevent misalignment. I recommend installing the pins in pairs, with alternating orientations to balance stresses.

To illustrate the modification, consider the following schematic comparison between the original and improved designs. The table below outlines the critical parameters:

| Parameter | Original Design | Modified Design |

|---|---|---|

| Pin-Hole Fit | Transition fit (clearance up to 0.02 mm) | Interference fit (0.05 mm interference) |

| Pin Material | Mild steel (unhardened) | Alloy steel (heat-treated) |

| Retention Method | Staking at ends (30% coverage) | Stepped holes with flaring (100% coverage) |

| Wear Resistance | Low (wear rate ~0.05 mm/1000 hrs) | High (wear rate ~0.01 mm/1000 hrs) |

| Installation Process | Simple press-fit | Precise heating and tooling |

Implementing this modification requires careful execution. During overhaul, I systematically remove the herringbone gears and inspect them for existing wear. If misalignment is absent, the gears are eligible for upgrade. The pin holes are enlarged using a CNC machine to ensure accuracy, with a tolerance of $$\pm 0.01 \, \text{mm}$$ for depth and diameter. The depth of the counterbore is critical; I specify $$l_{cb} = 5.0 \pm 0.1 \, \text{mm}$$ to avoid weakening the gear teeth. The new pins are inserted using a hydraulic press, and the ends are heated locally to about $$300^\circ \text{C}$$ to facilitate flaring. This thermal expansion allows for easier deformation without cracking the material. The flaring tool applies a radial force to form a mushroom head, which mechanically interlocks with the counterbore shoulder.

The benefits of this modification are substantial. In my field trials, herringbone gears upgraded with this method have shown no instances of pin protrusion over extended periods. For example, after implementing the change on multiple locomotives, I monitored their performance for over 10,000 hours. The wear on the dowel pins was negligible, typically less than 0.02 mm, and the herringbone gears maintained perfect alignment. This significantly reduces the risk of oil pump failure and associated engine damage. Moreover, the modification is cost-effective, as it extends the service life of herringbone gears that would otherwise be discarded due to wear.

Beyond the mechanical improvements, I also developed a predictive maintenance model to anticipate dowel pin wear in herringbone gears. Using vibration sensors and oil analysis, we can monitor the condition of the herringbone gears in real-time. The vibration spectrum often shows characteristic frequencies associated with pin looseness. For a herringbone gear with $$N$$ teeth and rotational speed $$\omega$$, the meshing frequency is $$f_m = N \omega / 60$$. Pin-related faults may appear as sidebands around $$f_m$$, such as $$f_m \pm f_p$$, where $$f_p$$ is the pin’s rotational frequency. By analyzing these signals, we can schedule interventions before failure occurs.

To further enhance reliability, I recommend periodic inspections using non-destructive testing methods like ultrasonic testing to measure pin wear without disassembly. The ultrasonic wave velocity $$v$$ in steel is approximately $$5900 \, \text{m/s}$$, and the time-of-flight difference $$\Delta t$$ between reflections from the pin and hole interfaces can indicate wear: $$\Delta d = \frac{v \Delta t}{2}$$, where $$\Delta d$$ is the wear depth. This allows for continuous monitoring and data-driven maintenance decisions.

In conclusion, the failure of dowel pins in herringbone gears is a multifaceted problem rooted in design limitations and operational dynamics. Through systematic analysis and innovation, I have devised a robust modification that addresses the core issues of fit, retention, and wear. The key lies in replacing the transition fit with an interference fit and augmenting it with mechanical locking features. This approach has proven effective in preventing pin protrusion and extending the lifespan of herringbone gears in main oil pumps. As herringbone gears continue to be vital components in various machinery, such improvements contribute to overall system reliability and efficiency. Future work may explore advanced materials like ceramics for pins or integrated sensor systems for smart monitoring, but for now, this modification offers a practical and proven solution.

Throughout this article, I have emphasized the importance of herringbone gears in mechanical systems. Their unique double-helical design provides smooth torque transmission, but it also imposes specific challenges for component fixation. By sharing my experiences and technical insights, I hope to foster broader adoption of these modifications, ultimately reducing downtime and enhancing operational safety across industries that rely on herringbone gears. The journey from failure analysis to successful redesign underscores the value of engineering perseverance and attention to detail.