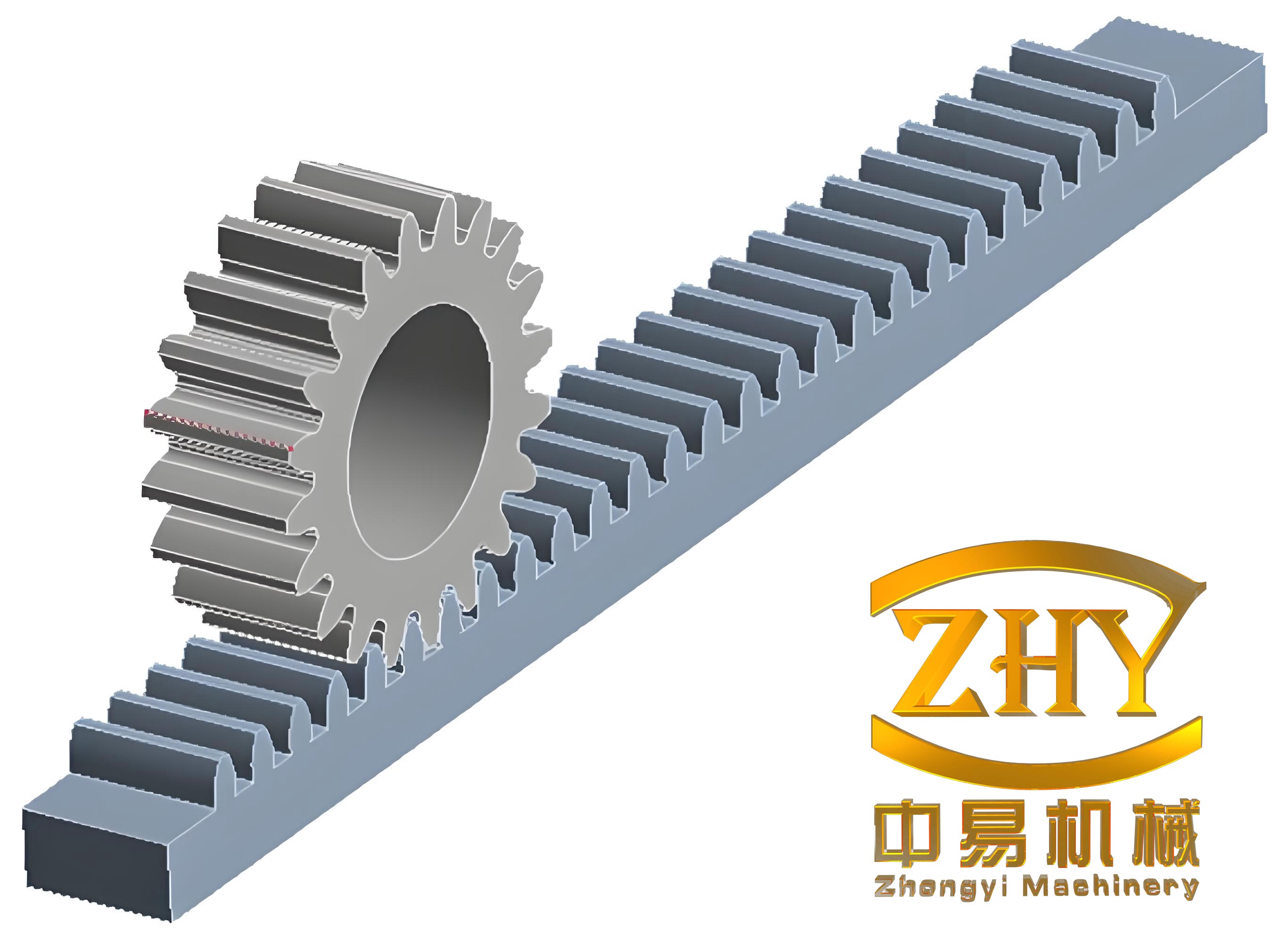

In this study, we investigate the bending strength of large modulus rack and pinion gear systems under uniform wear conditions, with a focus on applications such as ship lifts and heavy lifting platforms. The rack and pinion gear mechanism is widely used in industrial machinery due to its ability to convert rotational motion into linear motion efficiently. However, in high-load environments like the Three Gorges ship lift, the rack and pinion components are subjected to significant stresses, leading to wear and potential failure. Understanding the effects of wear on bending strength is crucial for ensuring the reliability and longevity of these systems. We employ a combination of analytical calculations and experimental validation to analyze the bending stress in gears under various wear states, including normal, 1/12 wear, 1/6 wear, and 1/4 wear conditions. This research aims to provide insights into the degradation mechanisms of rack and pinion gear systems and offer practical guidelines for maintenance and safety assessments.

The rack and pinion gear system consists of a gear (pinion) that meshes with a linear rack, transmitting force and motion. In large modulus applications, such as those with module sizes exceeding standard dimensions, the gear teeth are subjected to higher bending moments, making them susceptible to fatigue and wear. Uniform wear refers to a scenario where the tooth thickness decreases evenly across all teeth due to prolonged operation, affecting key parameters like load distribution and stress concentrations. To model this, we use the gear displacement method, which involves adjusting the gear’s profile through modification coefficients to simulate wear-induced changes. This approach allows us to study how wear impacts the bending stress along the tooth profile, particularly in single and double tooth contact regions.

The bending stress in a gear tooth is a critical factor in design and failure analysis. According to standard gear theory, the bending stress σF can be expressed as:

$$ \sigma_F = K_F \frac{F_t Y_{Fa} Y_{sa} Y_{\varepsilon}}{b_1 m} \leq [\sigma_F] $$

where KF is the load factor, Ft is the tangential force, YFa is the form factor, Ysa is the stress correction factor, Yε is the contact ratio factor, b1 is the face width, and m is the module. The load factor KF accounts for dynamic and distribution effects and is given by:

$$ K_F = K_A K_v K_{\alpha} K_{\beta} $$

Here, KA is the application factor, Kv is the dynamic factor, Kα is the load distribution factor, and Kβ is the face load factor. For a rack and pinion gear system, the load distribution factor Kα varies with the meshing position, as the gear rotates through single and double tooth contact zones. In double tooth contact regions, the load is shared between two pairs of teeth, reducing the stress on each tooth, whereas in single tooth contact, the entire load is borne by one tooth, leading to higher stress. The factor Kα can be modeled as:

$$ K_{\alpha} = \begin{cases}

\frac{\cos[b_0(\xi – \xi_m)]}{\cos[b_0(\xi – \xi_m)] + \cos[b_0(\xi + 1 – \xi_m)]} & \text{(for double tooth contact)} \\

1 & \text{(for single tooth contact)}

\end{cases} $$

where ξ, ξm, and b0 are parameters derived from the gear geometry and contact ratio. The contact ratio εα, which defines the average number of teeth in contact, is influenced by wear and is calculated as:

$$ \varepsilon_{\alpha} = \frac{1}{2\pi} \left[ Z_1 (\tan \alpha_{a1} – \tan \alpha’) + \frac{4(h_a^* – X – T)}{m \sin 2\alpha} \right] $$

In this equation, Z1 is the number of teeth on the pinion, αa1 is the pressure angle at the tip, α’ is the operating pressure angle, ha* is the addendum coefficient, X is the profile shift coefficient (used to model wear), and T is the mounting error. Under uniform wear, the profile shift coefficient X changes, reflecting the reduction in tooth thickness. For a worn gear, X is determined by:

$$ X = \frac{s_1 – (P / 2)}{2m \tan \alpha} $$

where s1 is the tooth thickness at the reference circle and P is the circular pitch. The form factor YFa and stress correction factor Ysa depend on the tooth geometry and are calculated using the 30° tangent method, which considers the critical section where bending stress is maximized. YFa is given by:

$$ Y_{Fa} = \frac{6(h_{Fa}/m) \cos \alpha_{a1}}{(s_1/m)^2 \cos \alpha} $$

and Ysa by:

$$ Y_{sa} = 1.2 + 0.16 \left( \frac{s_1}{h_{Fa}} \right) \left( \frac{s_1}{2r_{\rho f}} \right)^{1/(1.2 + 2.1 h_{Fa}/s_1)} $$

where hFa is the bending moment arm and rρf is the fillet radius. The contact ratio factor Yε is derived from εα as:

$$ Y_{\varepsilon} = 0.25 + \frac{0.75}{\varepsilon_{\alpha}} $$

These equations form the basis of our analytical model for evaluating bending stress under wear conditions. To validate this model, we conducted experiments on a vertical rack and pinion lifting mechanism simulator, designed to replicate the operating conditions of large modulus systems like the Three Gorges ship lift. The experimental setup included a gear and rack pair with a module of 10 mm, and we applied various loads to simulate different operational scenarios. The wear states were achieved by progressively reducing the tooth thickness through machining, corresponding to the theoretical wear levels.

The experimental apparatus consisted of a hydraulic loading system to apply tangential forces, and strain gauges were attached near the tooth roots to measure bending stresses. Data acquisition was performed using a static strain measurement system, capturing stress values at multiple meshing positions. We tested six load cases, representing different operational conditions such as ascending and descending under varying误载水深 (misload water depths) and wind effects, as outlined in the reference study. The tangential force Ft for each case was scaled down from the actual ship lift loads using a similarity principle, where the stress is inversely proportional to the product of face width and module. For instance, if the face width and module are reduced by factors n and t, respectively, the applied force in the experiment is Ft = F’t / (nt), where F’t is the full-scale force.

The following table summarizes the key parameters for the rack and pinion gear system under different wear states, based on our analytical calculations:

| Parameter | Normal Gear | 1/12 Wear Gear | 1/6 Wear Gear | 1/4 Wear Gear |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tooth thickness s (mm) | 28.27 | 25.91 | 24.74 | 21.20 |

| Profile shift coefficient X | 0 | -0.072 | -0.133 | -0.206 |

| Tip pressure angle αa1 (°) | 32.780 | 32.092 | 31.492 | 30.749 |

| Contact ratio εα | 1.7478 | 1.63 | 1.53 | 1.41 |

| Contact ratio factor Yε | 0.679 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.78 |

| Form factor YFa | 2.47 | 2.56 | 2.58 | 2.79 |

| Stress correction factor Ysa | 1.88 | 1.860 | 1.857 | 1.817 |

Using these parameters, we computed the bending stress along the tooth profile for each wear state and load case. The meshing process was divided into intervals: double tooth contact regions (B1C and DB2) and single tooth contact region (CD). The boundaries of these intervals shift with wear, as the contact ratio decreases. For example, in a normal gear, the single tooth contact region spans from a meshing radius of 149.08 mm to 153.17 mm, whereas in a 1/4 wear gear, it extends from 149.08 mm to 160.25 mm. This expansion of the single tooth contact zone increases the time proportion spent in high-stress conditions, exacerbating the risk of fatigue failure.

The load distribution factor Kα was calculated for each meshing position, and the results showed that as wear progresses, the single tooth contact region enlarges, leading to a higher proportion of time under elevated stress. The following table illustrates the division of meshing intervals for different wear states:

| Meshing Interval | Normal Gear (mm) | 1/12 Wear Gear (mm) | 1/6 Wear Gear (mm) | 1/4 Wear Gear (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Double tooth B1C | [143.77, 149.08] | [143.89, 149.08] | [144.21, 149.08] | [144.85, 149.08] |

| Single tooth CD | [149.08, 153.17] | [149.08, 155.45] | [149.08, 157.54] | [149.08, 160.25] |

| Double tooth DB2 | [153.17, 171] | [155.45, 171] | [157.54, 171] | [160.25, 171] |

Analytical results for bending stress revealed that stress levels increase with both wear severity and applied load. In single tooth contact regions, the stress is significantly higher than in double tooth contact areas. For instance, under a high-load condition (e.g.,工况 6), the bending stress in the single tooth zone of a 1/4 wear gear was approximately 25.4% higher than in a normal gear. This trend is consistent across all wear states, highlighting the detrimental effect of wear on gear performance. The proportion of time spent in single tooth contact also rises with wear; for a normal gear, it is 15.0%, but for a 1/4 wear gear, it increases to 42.7%, indicating accelerated degradation in the rack and pinion system.

To verify these analytical findings, we conducted experimental measurements on the test rig. Strain gauges were placed on multiple teeth, and stresses were recorded for each load case and wear state. The experimental data closely matched the analytical predictions, with a maximum error of 4.02% observed in the double tooth contact region under specific conditions. The following table compares the average bending stresses from analysis and experiment for the single tooth contact region under different loads:

| Load Case | Normal Gear (Analytical, MPa) | Normal Gear (Experimental, MPa) | 1/12 Wear Gear (Analytical, MPa) | 1/12 Wear Gear (Experimental, MPa) | 1/6 Wear Gear (Analytical, MPa) | 1/6 Wear Gear (Experimental, MPa) | 1/4 Wear Gear (Analytical, MPa) | 1/4 Wear Gear (Experimental, MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 45.2 | 44.8 | 48.5 | 48.1 | 50.9 | 50.5 | 56.7 | 56.2 |

| Case 2 | 52.1 | 51.6 | 55.8 | 55.3 | 58.6 | 58.1 | 65.3 | 64.7 |

| Case 3 | 61.3 | 60.7 | 65.7 | 65.1 | 69.0 | 68.4 | 76.9 | 76.2 |

| Case 4 | 70.5 | 69.9 | 75.6 | 74.9 | 79.4 | 78.7 | 88.5 | 87.8 |

| Case 5 | 79.7 | 79.0 | 85.5 | 84.8 | 89.8 | 89.1 | 100.1 | 99.3 |

| Case 6 | 88.9 | 88.2 | 95.4 | 94.6 | 100.2 | 99.4 | 111.7 | 110.8 |

The close agreement between analytical and experimental results validates our model and demonstrates its accuracy in predicting bending stress in rack and pinion gear systems under wear. The errors are within acceptable limits, ensuring the reliability of our approach for practical applications. Furthermore, the increase in stress with wear underscores the importance of regular monitoring and maintenance in rack and pinion installations to prevent unexpected failures.

In discussion, we emphasize that uniform wear not only elevates bending stress but also alters the dynamic behavior of the rack and pinion gear system. The expansion of single tooth contact zones leads to higher impact loads and vibration, which can accelerate other failure modes such as pitting and cracking. For engineers designing rack and pinion systems, our findings suggest that incorporating wear allowances in the initial design phase could enhance durability. Additionally, the gear displacement method provides a practical tool for assessing remaining life in service. The rack and pinion mechanism, being central to many industrial applications, benefits from such detailed stress analysis to optimize performance and safety.

In conclusion, our study comprehensively analyzes the bending strength of large modulus rack and pinion gear under uniform wear. Through analytical modeling and experimental validation, we show that wear significantly increases bending stress, particularly in single tooth contact regions, and prolongs the time under high-stress conditions. The rack and pinion gear system’s performance degrades with wear, necessitating proactive maintenance strategies. The methods developed here can be applied to various rack and pinion configurations, contributing to improved reliability in heavy machinery. Future work could explore the effects of non-uniform wear or combined loading conditions on rack and pinion dynamics.