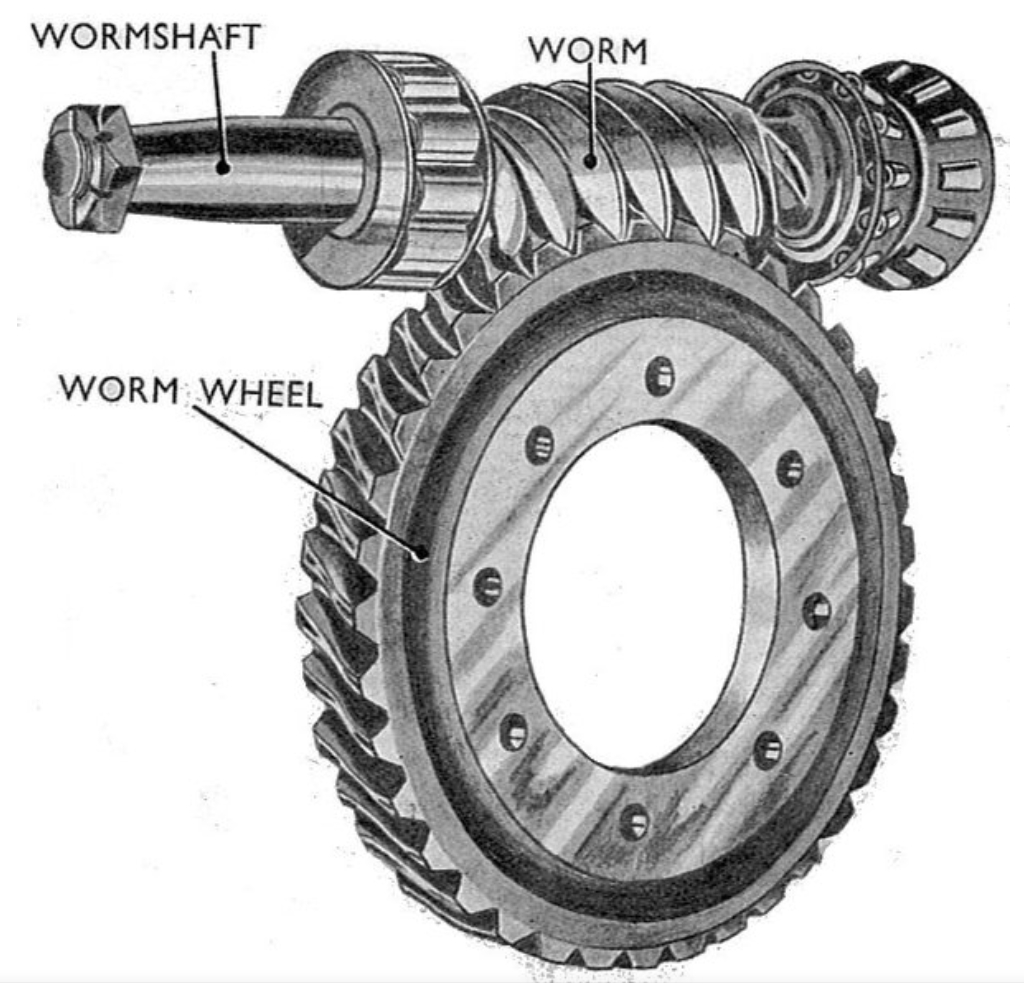

In the field of mechanical power transmission, worm gear drives are widely recognized for their ability to provide high reduction ratios, compact design, smooth operation, and shock load absorption. They find extensive applications in industries such as aerospace, medical equipment, construction, marine systems, and robotics. However, traditional worm gear drives often suffer from relatively low transmission efficiency and limited load-carrying capacity. A primary reason for these shortcomings is the inherent sliding motion between the conjugate tooth surfaces, which leads to significant friction, wear, and heat generation, ultimately degrading lubrication conditions. To address these challenges, researchers have proposed various innovative worm gear drive configurations aimed at improving meshing performance and lubrication.

One such novel configuration is the tapered roller enveloping end face worm gear drive. In this design, the worm wheel teeth are constituted by conical rollers that can rotate about their own axes, while the worm is generated as an envelope of a conical surface family. This arrangement aims to increase the number of simultaneously meshing tooth pairs, eliminate backlash, and, crucially, convert sliding friction into rolling friction through the use of bearings, thereby enhancing efficiency and durability. In this article, I will delve into a comprehensive analysis of the meshing performance of this tapered roller enveloping end face worm gear drive. Based on gear meshing theory and differential geometry, I will establish the mathematical model, derive the necessary equations, and evaluate key performance parameters. The influence of geometric design variables on these parameters will be systematically investigated to demonstrate the potential advantages of this worm gear drive.

The core of understanding any worm gear drive lies in its geometric and kinematic modeling. For the tapered roller enveloping end face worm gear drive, I establish a set of coordinate systems according to the principles of gear meshing and differential geometry. The fixed coordinate system for the worm is denoted as $\sigma_1(\mathbf{i}_1, \mathbf{j}_1, \mathbf{k}_1)$, with $\mathbf{k}_1$ as the worm axis. The fixed coordinate system for the worm wheel is $\sigma_2(\mathbf{i}_2, \mathbf{j}_2, \mathbf{k}_2)$, with $\mathbf{k}_2$ as the wheel axis. The moving coordinate systems attached to the worm and wheel are $\sigma_1′(\mathbf{i}_1′, \mathbf{j}_1′, \mathbf{k}_1′)$ and $\sigma_2′(\mathbf{i}_2′, \mathbf{j}_2′, \mathbf{k}_2′)$, respectively. The center distance is $A$. The angular velocities are $\boldsymbol{\omega}_1$ for the worm and $\boldsymbol{\omega}_2$ for the wheel, related by the transmission ratio $i_{12} = \omega_1 / \omega_2 = Z_2 / Z_1$, where $Z_1$ is the number of worm threads and $Z_2$ is the number of wheel teeth (rollers). The rotation angles are $\phi_1$ and $\phi_2$, with $\phi_2 = i_{21} \phi_1$ and $i_{21}=1/i_{12}$. An additional coordinate system $\sigma_0(\mathbf{i}_0, \mathbf{j}_0, \mathbf{k}_0)$ is fixed at the apex of the conical roller, with $\mathbf{k}_0$ along the roller’s axis. A moving frame $\sigma_p(\mathbf{e}_1, \mathbf{e}_2, \mathbf{n})$ is defined at the contact point $O_p$ on the roller surface.

The surface of the conical roller (the generating surface) in $\sigma_0$ is given by the vector equation:

$$\mathbf{r}_0 = x_0 \mathbf{i}_0 + y_0 \mathbf{j}_0 + z_0 \mathbf{k}_0$$

with the parametric form:

$$x_0 = (R + u \tan \beta) \cos \theta, \quad y_0 = (R + u \tan \beta) \sin \theta, \quad z_0 = u$$

where $R$ is the radius of the small end of the tapered roller, $\beta$ is the semi-cone angle, and $\theta$ and $u$ are the surface parameters.

Coordinate transformations between these systems are essential. The transformation from $\sigma_1’$ to $\sigma_2’$ involves a matrix $\mathbf{A}_{2’1′}$ with elements dependent on $\phi_1$ and $\phi_2$. The transformation from $\sigma_0$ to $\sigma_p$ is given by a matrix $\mathbf{A}_{p0}$ involving angles $\theta$ and $\beta$.

The relative velocity vector $\mathbf{v}^{(1’2′)}$ at the contact point, crucial for meshing analysis, is derived from kinematic relations. In the $\sigma_p$ frame, its components can be expressed as:

$$v_1^{(1’2′)} = -B_2 \sin \theta – B_3 \cos \theta,$$

$$v_2^{(1’2′)} = B_2 \sin \beta \cos \theta – B_1 \cos \beta – B_3 \sin \beta \sin \theta,$$

$$v_n^{(1’2′)} = B_1 \sin \beta + B_2 \cos \beta \cos \theta – B_3 \cos \beta \sin \theta,$$

where $B_1, B_2, B_3$ are functions of geometric parameters, angular velocities, and coordinates.

The fundamental condition for contact between two surfaces is that their relative velocity has no component along the common normal at the point of contact. This gives the meshing function $\Phi$:

$$\Phi = \mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{v}^{(1’2′)} = 0.$$

Substituting the expressions, the meshing equation for this worm gear drive is obtained:

$$\Phi = M_1 \cos \phi_2 + M_2 \sin \phi_2 + M_3 = 0,$$

where $M_1, M_2, M_3$ are functions of $R, \beta, \theta, u, a_2, b_2, c_2, A$, and $i_{21}$. Here $(a_2, b_2, c_2)$ are the coordinates of $O_0$ in $\sigma_2$.

The worm tooth surface is the envelope of the family of conical roller surfaces during the relative motion. Therefore, the worm surface equation $\mathbf{r}_{1′}$ in $\sigma_{1′}$ is derived by transforming $\mathbf{r}_0$ from $\sigma_0$ to $\sigma_{1′}$ via $\sigma_{2′}$, while simultaneously satisfying the meshing equation $\Phi=0$. The result is a system:

$$\mathbf{r}_{1′} = x_1 \mathbf{i}_{1′} + y_1 \mathbf{j}_{1′} + z_1 \mathbf{k}_{1′},$$

with

$$x_1 = \cos \phi_1 \cos \phi_2 (z_0 – a_2) + \cos \phi_1 \sin \phi_2 x_0 + y_0 \sin \phi_1 + A \cos \phi_1,$$

$$y_1 = \sin \phi_1 \cos \phi_2 (z_0 – a_2) + \sin \phi_1 \sin \phi_2 x_0 – y_0 \cos \phi_1 + A \sin \phi_1,$$

$$z_1 = \sin \phi_2 (a_2 – z_0) + \cos \phi_2 x_0,$$

where $u = f(\theta, \phi_2)$ is determined from the meshing equation, and $\phi_2 = i_{21} \phi_1$. This defines the worm tooth surface parametrically.

To assess the quality and performance of this worm gear drive, several key meshing performance parameters are analyzed. These parameters directly influence load capacity, lubrication, wear, and efficiency. The primary parameters considered are the induced normal curvature, the lubrication angle, the self-rotation angle of the roller, and the relative entrainment velocity.

The induced normal curvature $k_\sigma^{(1’2′)}$ at a contact point is the difference in normal curvatures of the two surfaces along a given direction. It is a critical factor in contact stress calculation. For this worm gear drive, the induced normal curvature in the direction of the contact line can be derived as:

$$k_\sigma^{(1’2′)} = -k_\sigma^{(2’1′)} = \frac{ -(\omega_2^{(1’2′)})^2 + \left( \frac{v_1^{(1’2′)} \cos \beta}{R + u \tan \beta} \right)^2 + (\omega_1^{(1’2′)})^2 }{\Psi},$$

where $\omega_1^{(1’2′)}, \omega_2^{(1’2′)}$ are components of the relative angular velocity, and $\Psi$ is a denominator related to the relative velocity magnitude. A smaller induced normal curvature generally leads to lower contact stress and is beneficial for elastohydrodynamic lubrication (EHL).

The lubrication angle $\mu$ is defined as the angle between the contact line and the relative velocity vector. An optimal lubrication angle close to $90^\circ$ promotes the formation of a hydrodynamic lubricant film. For this drive, it is calculated as:

$$\mu = \arcsin\left( \frac{u}{m n} \right),$$

where

$$u = v_1^{(1’2′)} \left( \frac{v_1^{(1’2′)} \cos \beta}{R + u \tan \beta} – \omega_2^{(1’2′)} \right) + v_2^{(1’2′)} \omega_1^{(1’2′)},$$

$$m = \sqrt{ \left( \frac{v_1^{(1’2′)} \cos \beta}{R + u \tan \beta} – \omega_2^{(1’2′)} \right)^2 + (\omega_1^{(1’2′)})^2 },$$

$$n = \sqrt{ (v_1^{(1’2′)})^2 + (v_2^{(1’2′)})^2 }.$$

The self-rotation angle $\mu_{z0}$ is the angle between the relative velocity vector and the axis of the conical roller ($\mathbf{k}_0$). A value near $90^\circ$ indicates favorable rolling conditions for the roller bearings. It is given by:

$$\mu_{z0} = \arccos\left( \frac{ |v_{12}^{(2)}| }{ \sqrt{ (v_{12}^{(1)})^2 + (v_{12}^{(2)})^2 } } \right),$$

where $v_{12}^{(1)}$ and $v_{12}^{(2)}$ are components of $\mathbf{v}^{(12)}$ in the $\sigma_p$ frame.

The relative entrainment velocity $v_{jx}$ is half the sum of the surface velocities of the worm and wheel along the contact normal direction. A higher entrainment velocity facilitates the formation of a thicker EHL film. It is calculated as:

$$v_{jx} = \frac{ v_{1’\sigma} + v_{2’\sigma} }{2},$$

where $v_{1’\sigma}$ and $v_{2’\sigma}$ are the normal components of the absolute velocities of the worm and wheel surfaces at the contact point, respectively.

The performance of this worm gear drive is significantly influenced by its geometric design parameters. I will now analyze the effects of three key parameters: the small end radius $R$ of the tapered roller, the throat diameter coefficient $k$ (where the worm throat diameter $d_1 = kA$), and the semi-cone angle $\beta$ of the roller. For a baseline configuration, I assume: center distance $A = 140 \text{ mm}$, worm threads $Z_1 = 1$, wheel teeth $Z_2 = 25$, and typical values for other parameters unless varied. The analysis is performed computationally, evaluating the performance parameters across the meshing zone (from entry to exit).

| Parameter | Symbol | Baseline Value | Analysis Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small End Radius | $R$ | 5.5 mm | 4.5 to 6.5 mm |

| Throat Diameter Coefficient | $k$ | 0.3 | 0.2 to 0.4 |

| Semi-Cone Angle | $\beta$ | 4° | 2° to 6° |

Effect of Small End Radius $R$: The radius $R$ directly affects the size and curvature of the conical roller.

- Induced Normal Curvature: As $R$ increases, the induced normal curvature decreases over the entire meshing zone. This is beneficial for reducing contact stress and improving EHL conditions.

- Lubrication Angle: The lubrication angle decreases from the entry to the exit side of the mesh. With increasing $R$, the lubrication angle becomes smaller, and its rate of change across the mesh becomes more pronounced, especially on the exit side. While lower angles are less ideal, the values generally remain within a functional range.

- Relative Entrainment Velocity: The entrainment velocity decreases from entry to exit. Interestingly, on the left tooth flank (one side of the worm thread), a larger $R$ increases the entrainment velocity, whereas on the right flank, it decreases the velocity. This asymmetry must be considered in design.

- Self-Rotation Angle: The self-rotation angle decreases from entry to exit. A larger $R$ results in a smaller self-rotation angle. However, when $R$ is smaller, the difference between entry and exit angles is reduced, leading to more uniform roller motion.

| Performance Parameter | Trend on Left Flank | Trend on Right Flank | Overall Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Normal Curvature $k_\sigma^{(1’2′)}$ | Decreases | Decreases | Improved load capacity & lubrication |

| Lubrication Angle $\mu$ | Decreases | Decreases | Potentially less favorable film formation |

| Entrainment Velocity $v_{jx}$ | Increases | Decreases | Mixed effect; flank-dependent |

| Self-Rotation Angle $\mu_{z0}$ | Decreases | Decreases | Less ideal rolling for roller bearings |

Effect of Throat Diameter Coefficient $k$: This coefficient scales the worm size relative to the center distance, affecting the worm’s curvature and the contact pattern.

- Induced Normal Curvature: On the left flank, induced curvature increases from entry to exit. For smaller $k$, the curvature is lower in the first half of mesh but higher in the second half. On the right flank, curvature decreases from entry to exit, and it increases overall with larger $k$.

- Lubrication Angle: The lubrication angle decreases from entry to exit. A smaller throat diameter coefficient ($k$) leads to a larger variation in the lubrication angle across the mesh.

- Relative Entrainment Velocity: Entrainment velocity decreases from entry to exit. From entry to mid-mesh, a larger $k$ reduces the velocity; from mid-mesh to exit, a larger $k$ increases it. This non-monotonic behavior requires careful optimization.

- Self-Rotation Angle: The self-rotation angle decreases from entry to exit. From entry to mid-mesh, a larger $k$ slightly decreases the angle; from mid-mesh to exit, a larger $k$ increases it. Thus, $k$ can be tuned to achieve more uniform self-rotation.

| Performance Parameter | Trend on Left Flank (Entry to Mid) | Trend on Left Flank (Mid to Exit) | Overall Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Normal Curvature | Increases with $k$ | Decreases with $k$ | Complex; optimal $k$ needed for balance |

| Lubrication Angle | Decreases with $k$ (generally) | Decreases with $k$ (generally) | Smaller $k$ gives larger angle variation |

| Entrainment Velocity | Decreases with $k$ | Increases with $k$ | Non-linear effect; design compromise |

| Self-Rotation Angle | Slightly decreases with $k$ | Increases with $k$ | $k$ can be used to flatten distribution |

Effect of Semi-Cone Angle $\beta$: This angle defines the taper of the roller, influencing the contact geometry and kinematics.

- Induced Normal Curvature: The induced normal curvature decreases as $\beta$ increases. This is a significant and beneficial trend, as a larger $\beta$ consistently lowers curvature, reducing contact stress.

- Lubrication Angle: The lubrication angle decreases with increasing $\beta$, and the rate of decrease across the mesh becomes steeper. Thus, while a larger $\beta$ helps curvature, it may compromise the lubrication angle.

- Relative Entrainment Velocity: Entrainment velocity decreases from entry to exit. On the left flank, a larger $\beta$ increases the entrainment velocity. On the right flank, a larger $\beta$ decreases it. This flank-dependent behavior is similar to the effect of $R$.

- Self-Rotation Angle: The self-rotation angle decreases with increasing $\beta$. A smaller $\beta$ yields a larger self-rotation angle, which is more desirable for roller bearing operation.

| Performance Parameter | Trend on Left Flank | Trend on Right Flank | Overall Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Normal Curvature | Decreases | Decreases | Very favorable for stress reduction |

| Lubrication Angle | Decreases | Decreases | Trade-off with curvature benefit |

| Entrainment Velocity | Increases | Decreases | Asymmetric effect; left flank benefits |

| Self-Rotation Angle | Decreases | Decreases | Less favorable for roller motion |

The comprehensive analysis reveals that the tapered roller enveloping end face worm gear drive exhibits promising meshing characteristics. The mathematical model successfully captures the geometry and kinematics. The derived performance parameters provide quantitative measures for evaluation. Key findings from the parametric study include:

- The induced normal curvature, a direct indicator of contact stress, is generally low and can be further reduced by increasing the roller’s small end radius $R$ or its semi-cone angle $\beta$. This is a significant advantage for this type of worm gear drive.

- The lubrication angle and self-rotation angle tend to decrease from the entry to the exit of the mesh. While larger $R$ and $\beta$ reduce these angles, their absolute values across much of the mesh remain sufficiently high to support effective lubricant film formation and roller rotation, especially on the left tooth flank which often shows better performance.

- The relative entrainment velocity, crucial for EHL, shows complex behavior. It is flank-dependent and influenced differently by each parameter. However, on the left flank—which typically experiences more load in such drives—increasing $R$ or $\beta$ can enhance the entrainment velocity, promoting better lubrication.

- The throat diameter coefficient $k$ has a non-linear and multifaceted influence. It allows designers to tune the performance distribution across the mesh, potentially balancing the entry and exit conditions.

Comparing the left and right flanks of the worm thread, the left flank consistently demonstrates superior performance in terms of lower induced curvature and higher entrainment velocity for increased $R$ and $\beta$. This suggests that the left flank likely carries more load and enjoys better lubrication conditions, which is advantageous for the overall durability of the worm gear drive.

From a design perspective, there are clear trade-offs. For instance, increasing $\beta$ greatly reduces contact stress (beneficial) but also reduces the lubrication and self-rotation angles (potentially detrimental). Therefore, an optimal design of this worm gear drive requires a multi-objective optimization that considers all performance parameters simultaneously, possibly weighting the left flank performance more heavily. The parametric trends provided here serve as a valuable guide for such optimization.

In conclusion, the tapered roller enveloping end face worm gear drive presents a viable and improved alternative to conventional worm gear drives. Its inherent design, featuring rotating conical rollers, aims to mitigate sliding friction. The meshing performance analysis confirms that it possesses favorable characteristics such as low induced normal curvature and reasonably good lubrication potential. The systematic study of geometric parameters like roller small end radius, throat diameter coefficient, and semi-cone angle provides deep insights into how the performance of this worm gear drive can be tailored. Future work could involve experimental validation, detailed thermal analysis, fatigue life prediction, and full-scale multi-parameter optimization to realize the full potential of this innovative worm gear drive in practical applications.

The mathematical framework established here is robust and can be extended to account for manufacturing errors, assembly misalignments, and dynamic loads. Furthermore, the principles could be applied to similar gear drives involving enveloping surfaces and rolling contacts. The continued exploration and refinement of such advanced worm gear drives are essential for meeting the ever-growing demands for efficient, reliable, and compact power transmission systems across various industries.