In modern manufacturing, the demand for high-precision transmission components has driven the adoption of net-shape forming processes, particularly for complex parts like straight bevel gears. As a key element in power transmission systems, the straight bevel gear plays a critical role in applications such as automotive differentials, where accuracy directly influences performance and efficiency. Traditional machining methods for straight bevel gears often involve material removal, leading to waste and potential compromises in mechanical properties. In contrast, cold forging offers a sustainable alternative by enabling near-net-shape production, which enhances material utilization and improves grain structure. However, the cold forging process for straight bevel gears introduces challenges like springback, where elastic recovery after deformation causes deviations from the intended geometry. This springback phenomenon can result in dimensional inaccuracies that affect the meshing behavior and longevity of the gear. Therefore, understanding and mitigating springback is essential for achieving the desired precision in straight bevel gear manufacturing.

My investigation focuses on the cold forging process for straight bevel gears, employing numerical simulations to analyze material flow, stress distribution, and springback behavior. The straight bevel gear, characterized by its conical shape and straight teeth, requires precise control during forming to ensure proper tooth profile and contact patterns. In this study, I developed a finite element model to simulate the entire cold forging sequence, from initial billet deformation to final springback. The model accounts for material plasticity, friction, and elastic recovery, providing insights into how the straight bevel gear responds to unloading. Based on the simulation results, I implemented a die modification strategy using a reverse compensation method to correct for springback-induced errors. This approach involves iteratively adjusting the die cavity based on deviation data, ultimately reducing geometric inaccuracies. Through this work, I aim to demonstrate that cold forging, combined with advanced simulation techniques, can produce straight bevel gears with high dimensional accuracy, thereby reducing the need for post-processing and lowering production costs.

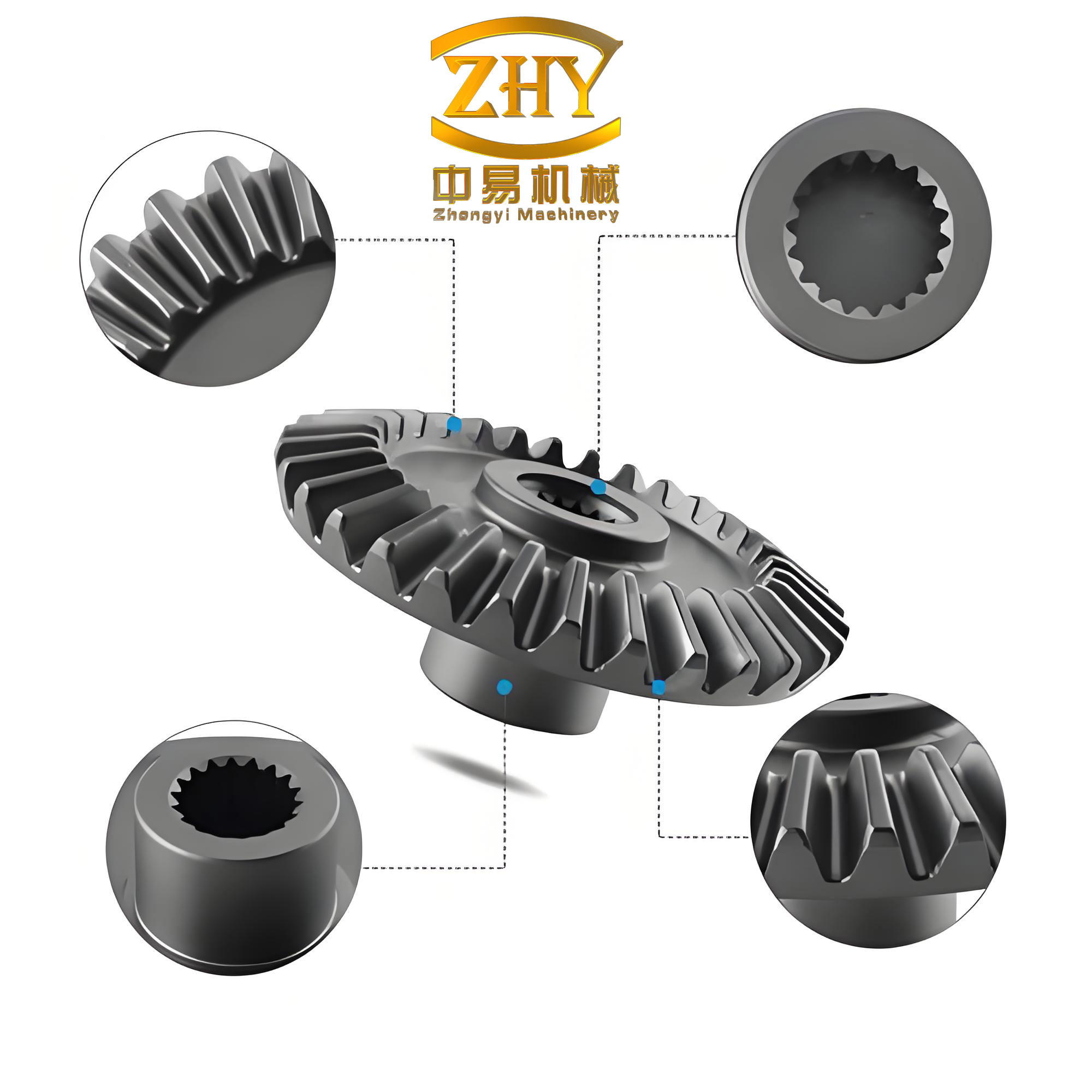

The cold forging process for straight bevel gears typically involves several stages: billet preparation, forming, and finishing. For the straight bevel gear studied here, the material is 20CrMnTi steel, which is annealed and subjected to phosphating and saponification to reduce friction and prevent galling. The forming stage uses a closed-die setup with upper and lower punches and a tooth-profile die cavity. As the upper punch descends, the billet undergoes radial upsetting and lateral flow, gradually filling the die cavity to form the teeth of the straight bevel gear. The final stage includes a coining step to refine the tooth profile and ensure full densification. This process is efficient but sensitive to parameters like die geometry and lubrication, which influence springback. To model this, I set up a finite element analysis using a one-tenth sector model to reduce computational cost while maintaining accuracy. The billet was treated as a rigid-plastic material initially, but for springback analysis, it was switched to an elastoplastic model to capture elastic effects. The dies were modeled as rigid bodies, with a shear friction coefficient of 0.12 and a forming speed of 30 mm/s. This setup allowed me to simulate the material flow and identify critical areas where springback occurs in the straight bevel gear.

During the simulation, I observed distinct phases of deformation for the straight bevel gear. Initially, the billet experiences radial compression as the upper punch moves downward, causing the material to spread laterally. This is followed by tooth filling, where the metal flows into the die cavities, starting from the small end of the straight bevel gear and progressing toward the large end. The final phase involves coining, where the lower punch applies pressure to ensure complete filling and surface finish. The forming load curve shows a peak at the end of tooth filling, indicating high resistance as the material conforms to the die. This load distribution is crucial for understanding springback, as areas with higher stress tend to exhibit greater elastic recovery. For instance, the tooth tips of the straight bevel gear, which experience significant deformation resistance, store more elastic strain energy, leading to larger springback upon unloading. The simulation results revealed that the straight bevel gear’s tooth profile undergoes non-uniform expansion after ejection, with deviations varying along the tooth height and from the small to large end.

To quantify springback in the straight bevel gear, I extracted coordinate data from multiple points on the tooth surface before and after unloading. The tooth surface was divided into N sections from the small to large end, and M points were sampled along each tooth profile line. The springback value Δs at each point was calculated as the difference in position:

$$ \Delta s = \sqrt{(x_2 – x_1)^2 + (y_2 – y_1)^2 + (z_2 – z_1)^2} $$

where (x1, y1, z1) and (x2, y2, z2) are the coordinates before and after springback, respectively. This analysis showed that springback is minimal near the pitch line of the straight bevel gear, where the tooth thickness is largest, and increases toward the tooth tip and root. For example, at the pitch line, springback was approximately 0.02 mm, while near the tooth tip, it reached up to 0.14 mm. This pattern is attributed to the direction of material flow during forming: metal moves from the core toward the tooth tips, accumulating elastic energy in regions with higher deformation. Upon unloading, this energy releases, causing the material to rebound outward. The velocity field after unloading confirmed this, showing flow from the root to the tip and from the small to large end of the straight bevel gear. This non-uniform springback necessitates die modifications to compensate for the deviations and achieve the target gear geometry.

I applied a reverse compensation method to modify the die cavity for the straight bevel gear. This method involves calculating the deviation between the sprung-back gear and the target profile, then applying an inverse offset to the die surface. The steps are as follows: First, I obtained the coordinates of the deformed tooth surface after springback and computed the deviation vector δ at each point. The compensation vector C is then defined as:

$$ C = -\delta $$

This vector is applied to the target surface to generate a modified die profile. The compensated points are fitted into a smooth curve, and the die cavity is updated accordingly. I iterated this process twice to refine the accuracy. After the first modification, the springback resulted in negative deviations, indicating over-compensation. After the second modification, the maximum deviation was reduced to -0.025 mm, with minimal error near the pitch line. The table below summarizes the springback values and deviations at different stages for selected points on the tooth profile of the straight bevel gear.

| Point Location | Initial Springback (mm) | Deviation After First Modification (mm) | Deviation After Second Modification (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pitch Line | 0.02 | -0.01 | 0.00 |

| Tooth Root | 0.08 | -0.05 | -0.015 |

| Tooth Tip | 0.14 | -0.10 | -0.025 |

The effectiveness of the die modification was further validated through contact pattern analysis. After forging with the modified die, the straight bevel gear exhibited a uniform contact area during meshing tests, indicating that the springback compensation successfully restored the intended tooth geometry. This is critical for ensuring smooth power transmission and minimizing noise in applications involving straight bevel gears. The reverse compensation method proved more suitable than alternatives like profile shift or base circle modification, as it accounts for the complex, non-springback behavior of the straight bevel gear tooth surface. For instance, profile shift assumes uniform springback along the tooth, which is not the case for straight bevel gears due to their conical shape. In contrast, reverse compensation addresses local deviations directly, making it ideal for high-precision requirements.

In discussing the results, it is evident that springback in cold-forged straight bevel gears is influenced by several factors, including material properties, die design, and process parameters. The elastic modulus E and yield strength σ_y of the material play a key role in springback magnitude. The springback angle θ can be approximated for bending-dominated regions using:

$$ \theta = \frac{M L}{E I} $$

where M is the bending moment, L is the characteristic length, E is the elastic modulus, and I is the moment of inertia. For the straight bevel gear, the tooth profile behaves like a cantilever beam under load, leading to greater springback at the tips. Additionally, friction conditions affect material flow; higher friction can increase resistance and elastic energy storage. To generalize these findings, I derived a springback prediction model for straight bevel gears based on finite element data. The model relates springback Δs to effective strain ε_eff and stress σ_eff:

$$ \Delta s = k \cdot \frac{\sigma_{\text{eff}}}{E} \cdot \epsilon_{\text{eff}}^n $$

where k and n are material constants. For 20CrMnTi steel, k ≈ 0.5 and n ≈ 0.2 were calibrated from simulation results. This model can help in optimizing process parameters for straight bevel gears, such as die angle and forming speed, to minimize springback. For example, increasing the forming speed may reduce springback by lowering flow stress, but it could also lead to incomplete filling. Thus, a balance must be struck through iterative simulation and die modification.

The economic implications of this approach are significant for straight bevel gear production. By using numerical simulation to predict and compensate for springback, manufacturers can reduce trial-and-error in die manufacturing, shortening development cycles and cutting costs. Traditional methods often require multiple die iterations, each involving costly machining and testing. In contrast, the virtual modification process allows for rapid optimization without physical prototypes. For high-volume production of straight bevel gears, such as in automotive applications, this can lead to substantial savings. Moreover, the improved accuracy enhances the performance and durability of the straight bevel gear, reducing warranty claims and maintenance costs. As industries move toward lightweight and efficient designs, the ability to produce precise straight bevel gears through cold forging will become increasingly valuable.

In conclusion, my analysis demonstrates that cold forging is a viable method for manufacturing straight bevel gears, but it requires careful attention to springback. Through finite element simulation, I identified that springback in straight bevel gears is non-uniform, with maximum values at the tooth tips and minimal values at the pitch line. The reverse compensation method effectively corrected these deviations, resulting in straight bevel gears with high dimensional accuracy after two modification cycles. This approach leverages advanced modeling techniques to address real-world manufacturing challenges, offering a pathway to more efficient and cost-effective production of straight bevel gears. Future work could explore the integration of machine learning for faster springback prediction or the application of this method to other gear types, further expanding the benefits of cold forging in precision engineering.