In the field of precision mechanical transmission, strain wave gear systems have emerged as a pivotal technology due to their high reduction ratios, compact design, and exceptional accuracy. As a researcher deeply involved in gear design, I have observed that the tooth profile geometry plays a crucial role in determining the meshing performance, load distribution, and overall efficiency of strain wave gear drives. Traditional design approaches, while functional, often encounter limitations in achieving optimal conjugate engagement across the entire tooth flank. This article presents a novel bidirectional conjugate design method specifically developed for double-circular-arc tooth profiles in strain wave gearing. The method addresses inherent uncertainties in conventional unidirectional conjugate approaches and enhances meshing characteristics through a synergistic calculation of both flexspline and circular spline profiles.

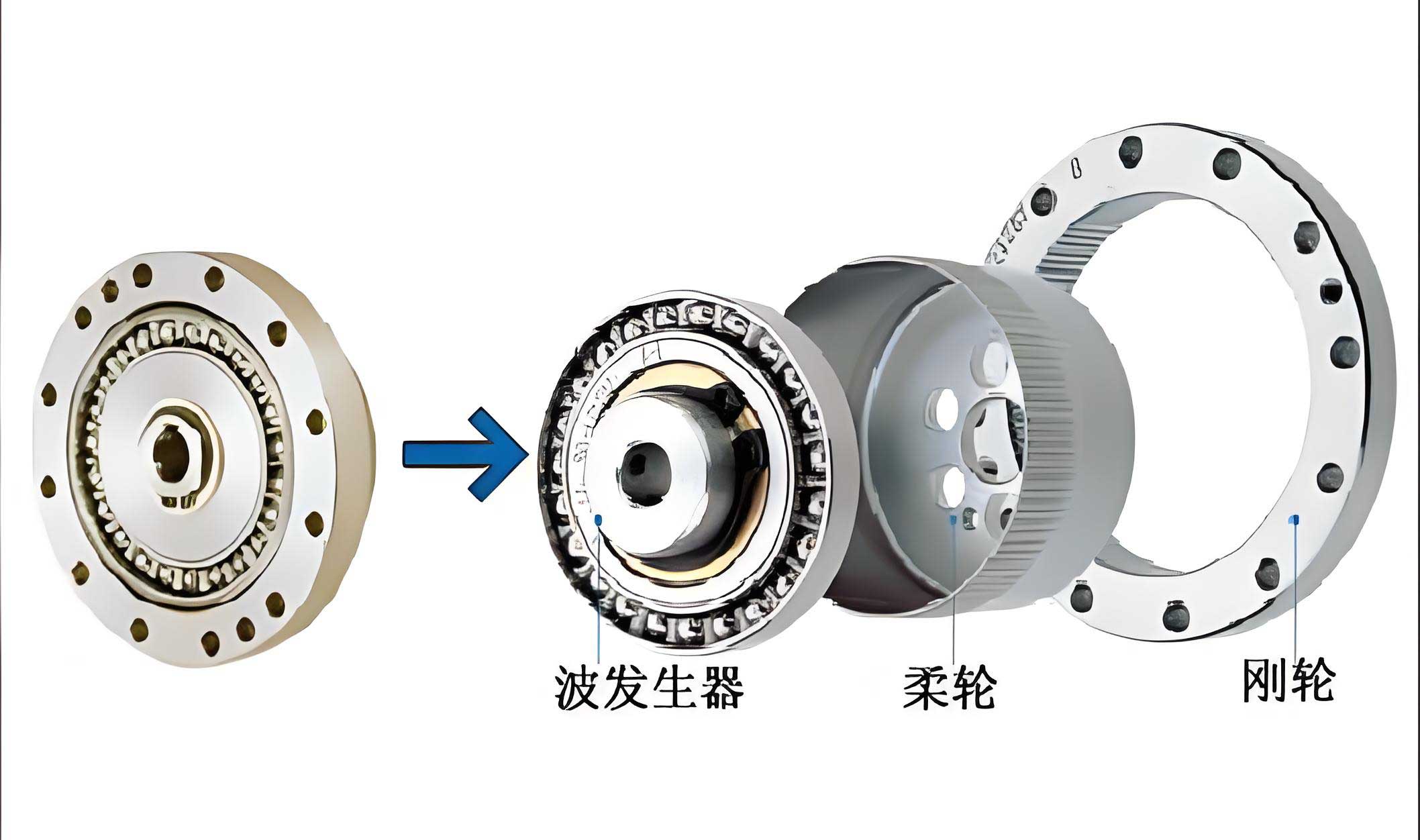

The fundamental operation of a strain wave gear relies on the elastic deformation of a flexible component, known as the flexspline, by a wave generator. This deformation creates a traveling wave that engages teeth with a rigid circular spline, resulting in motion reduction. The double-circular-arc profile, comprising two circular arc segments connected by a common tangent, has been widely adopted for strain wave gear due to its favorable stress distribution and improved contact conditions. However, the design of such profiles using unidirectional conjugate methods often leads to ambiguous conjugate geometry for the convex arc of the circular spline, potentially compromising meshing continuity and load capacity. Our proposed bidirectional conjugate method resolves this by iteratively computing conjugate profiles from both the flexspline and circular spline perspectives, ensuring full and consistent engagement.

To establish a mathematical foundation for strain wave gear design, we begin by defining the coordinate systems and kinematic relationships. The following assumptions are made for planar meshing analysis: the neutral curve of the flexspline does not elongate during deformation; all characteristic curves after deformation are considered equidistant from the original curve; teeth are uniformly distributed along the original curve; and the wave generator is treated as a rigid body. We define three primary coordinate systems: the wave generator coordinate system {OXY}, the flexspline tooth coordinate system {o1x1y1}, and the circular spline coordinate system {o2x2y2}. The radius of the flexspline’s neutral layer before deformation, \( r_m \), is given by:

$$ r_m = \frac{D_b + \delta_f}{2} $$

where \( D_b \) is the outer diameter of the flexible bearing and \( \delta_f \) is the wall thickness at the tooth root of the flexspline. The radial displacement of the deformed neutral curve, \( \omega(\phi) \), is determined by the contour of the wave generator, with \( \phi \) being the angular position relative to the major axis of the wave generator. The vector radius of the deformed curve is:

$$ \rho(\phi) = r_m + \omega(\phi) $$

The circumferential displacement \( \upsilon \) and the normal rotation angle \( \mu \) of the neutral layer are derived as:

$$ \upsilon = -\int \omega \, d\phi, \quad \mu = -\arctan\left(\frac{\dot{\rho}}{\rho}\right) $$

where \( \dot{\rho} \) denotes the derivative with respect to \( \phi \). Based on the non-elongation assumption and geometric relations, we have:

$$ \phi_1 = \phi + \frac{\upsilon}{r_m}, \quad \phi_2 = \left(\frac{z_1}{z_2}\right)\phi, \quad \gamma = \phi_1 – \phi_2, \quad \Phi = \mu + \gamma $$

Here, \( \phi_1 \) and \( \phi_2 \) are the rotation angles of the deformed flexspline end and the circular spline, respectively; \( z_1 \) and \( z_2 \) are the tooth numbers of the flexspline and circular spline; \( \gamma \) is the angular difference between them; and \( \Phi \) is the angle between the y-axes of the flexspline and circular spline coordinate systems.

The unidirectional conjugate design method for double-circular-arc profiles in strain wave gear typically involves prescribing the convex arc of the flexspline, computing its conjugate curves to obtain potential circular spline profiles, and then fitting circular arcs to these curves. However, this process often results in uncertainty for the convex arc segment of the circular spline, as it must be selected from two possible conjugate curves, leading to suboptimal meshing conditions such as limited contact area or non-conjugate engagement. To overcome this, our bidirectional conjugate method integrates a reverse computation step, ensuring that both arcs of the flexspline are conjugate with the circular spline’s convex arc.

The core procedure of the bidirectional conjugate design method is outlined as follows:

- Preset the parameters for the convex circular arc of the flexspline.

- Perform conjugate calculation via the envelope method to obtain conjugate curves for the circular spline.

- Fit these conjugate curves to define the double-circular-arc profile of the circular spline.

- Execute a reverse conjugate calculation from the circular spline’s convex arc to derive the conjugate curve for the flexspline.

- Fit this curve to determine the concave arc of the flexspline, combining it with the preset convex arc to form the complete flexspline tooth profile.

This bidirectional approach guarantees conjugate engagement across both arc segments, enhancing the meshing performance of the strain wave gear system.

In the flexspline coordinate system {o1x1y1}, the convex arc segment \( \overset{\frown}{ST_1} \) is defined by preset parameters including the tooth thickness ratio \( K \), addendum height \( h_{a1} \), dedendum height \( h_{f1} \), and arc inclination angle \( \beta \). The pitch circle diameter of the flexspline \( d_1 \) is calculated as:

$$ d_1 = D_b + 2\delta_f + 2h_{f1} $$

The pitch circle tooth thickness \( S_a \) is:

$$ S_a = \frac{\pi d_1}{(1+K)z_1} $$

The radius of the flexspline’s convex arc \( \rho_a \) is:

$$ \rho_a = \frac{h_{a1} – h_l}{\sin \beta} $$

where \( h_l \) is the working tooth height of the convex arc. The distance from the arc center to the symmetry axis is:

$$ l_a = \frac{\rho_a}{\cos \beta} – \frac{S_a}{2} $$

The coordinates of the convex arc in {o1x1y1}, parameterized by arc length \( s \) from the tooth tip A, are expressed as:

$$ x_1(s) = \rho_a \cos(\alpha_1 – s/\rho_a) + x_{Oa}, \quad y_1(s) = \rho_a \sin(\alpha_1 – s/\rho_a) + y_{Oa} $$

with \( x_{Oa} = -l_a \), \( y_{Oa} = h_{f1} + \delta_f/2 \), and \( \alpha_1 = \arcsin(h_{a1}/\rho_a) \). The parameter \( s \) ranges from \( 0 \) to \( \rho_a(\alpha_1 – \beta) \).

To obtain the conjugate profiles on the circular spline, we transform the flexspline tooth coordinates to the circular spline system {o2x2y2} using the homogeneous transformation matrix:

$$

\begin{bmatrix} x_{21} \\ y_{21} \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos\Phi & \sin\Phi & \rho \sin\gamma \\ -\sin\Phi & \cos\Phi & \rho \cos\gamma \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ y_1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}

$$

The envelope condition for conjugate tooth profiles is given by:

$$

\frac{\partial x_{21}}{\partial s} \frac{\partial y_{21}}{\partial \phi} – \frac{\partial x_{21}}{\partial \phi} \frac{\partial y_{21}}{\partial s} = 0

$$

Solving this equation numerically for discrete values of \( s \) yields the conjugate curve points, which are segregated into two segments: \( \overset{\frown}{CT_1} \) and \( \overset{\frown}{CT_2} \). These discrete points are then fitted via least-squares circle fitting to define the concave arc \( \overset{\frown}{SA_2} \) and convex arc \( \overset{\frown}{ST_2} \) of the circular spline, respectively. The circular spline’s complete working profile is formed by connecting these arcs with a common tangent segment.

Subsequently, the convex arc \( \overset{\frown}{ST_2} \) of the circular spline is used for reverse conjugate computation. In {o2x2y2}, the arc coordinates are parameterized similarly. Applying the inverse coordinate transformation and the envelope condition, we obtain the conjugate curve \( \overset{\frown}{CT_3} \) in the flexspline system. Fitting \( \overset{\frown}{CT_3} \) to a circular arc defines the concave arc \( \overset{\frown}{SA_1} \) of the flexspline. Combining \( \overset{\frown}{SA_1} \) with the preset convex arc \( \overset{\frown}{ST_1} \) via a common tangent yields the full double-circular-arc profile of the flexspline. This bidirectional process ensures mutual conjugacy between the arcs of both components in the strain wave gear assembly.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of our method, we present a design example based on an XB50-type strain wave gear with the following specifications: module \( m = 0.25 \, \text{mm} \), flexspline tooth number \( z_1 = 200 \), circular spline tooth number \( z_2 = 202 \), radial deformation coefficient \( \omega_0^* = 1 \), bearing outer diameter \( D_b = 50 \, \text{mm} \), tooth root wall thickness \( \delta_f = 0.675 \, \text{mm} \). Key design parameters for both unidirectional and bidirectional methods are listed in Table 1. Note that the bidirectional method requires fewer preset parameters as the flexspline’s concave arc is derived computationally.

| Parameter | Unidirectional Method | Bidirectional Method |

|---|---|---|

| Pitch circle tooth thickness ratio \( K \) | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Arc inclination angle \( \beta \) (°) | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| Convex arc working tooth height coefficient \( h_l^* \) | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| Concave arc radius coefficient \( \rho_f^* \) | 2.0528 | — |

| Concave arc center offset coefficient \( l_f^* \) | 2.7231 | — |

The computed tooth profile parameters for both methods are summarized in Table 2. The bidirectional method yields a flexspline with a thicker root section and a more harmonious arc geometry, which contributes to improved strength and meshing engagement.

| Parameter | Bidirectional Method | Unidirectional Method |

|---|---|---|

| Flexspline | ||

| Convex arc radius \( \rho_a \) | 0.2681 | 0.2701 |

| Convex arc center offset \( l_a \) | 0.0930 | 0.0982 |

| Convex arc working height \( h_l \) | 0.1541 | 0.1898 |

| Concave arc radius \( \rho_f \) | 0.4638 | 0.5132 |

| Concave arc center offset \( l_f \) | 0.6390 | 0.6808 |

| Concave arc vertical offset \( b_f \) | 0.0975 | 0.0840 |

| Tooth tip thickness \( h_{t1} \) | 0.0959 | 0.0182 |

| Pitch circle tooth thickness \( S_a \) | 0.3696 | 0.3484 |

| Circular Spline | ||

| Convex arc radius \( \rho_p \) | 0.4535 | 0.4562 |

| Convex arc center offset \( l_p \) | 0.6310 | 0.6302 |

| Convex arc vertical offset \( b_p \) | 0.0911 | 0.0933 |

| Concave arc radius \( \rho_q \) | 0.2761 | 0.2785 |

| Concave arc center offset \( l_q \) | 0.0981 | 0.1034 |

| Concave arc vertical offset \( b_q \) | 0.0054 | 0.0057 |

| Tooth tip thickness \( h_{t2} \) | 0.0900 | 0.0880 |

Meshing backlash analysis provides a quantitative assessment of engagement quality in strain wave gear systems. Backlash is defined as the circumferential clearance between the flexspline and circular spline tooth profiles under no-load conditions. A backlash value less than 0.003 mm indicates potential contact. The distribution of minimum backlash along the tooth profile for both design methods is analyzed. For the bidirectional method, the actively meshing profile length reaches up to 0.53 mm, whereas the unidirectional method achieves only 0.22 mm. This substantial increase confirms that the bidirectional design enables more extensive tooth contact.

Furthermore, we examine the position of the meshing point, where the minimum backlash occurs at each angular position \( \phi \). The results reveal that for the bidirectional method, the meshing point transitions across all three segments of the double-circular-arc profile: the concave arc \( \overset{\frown}{CD} \) for \( \phi < 4^\circ \), the common tangent segment \( \overset{\frown}{BC} \) for \( 4^\circ \leq \phi \leq 13.5^\circ \), and the convex arc \( \overset{\frown}{AB} \) for \( \phi > 13.5^\circ \). In contrast, the unidirectional method confines meshing to the convex arc alone. This transition facilitates multi-point contact, a phenomenon where multiple points on a single tooth pair engage simultaneously, thereby distributing load more evenly.

To quantify multi-point contact, we analyze the minimum backlash distributions separately for each profile segment. Table 3 summarizes the angular ranges where two segments exhibit nearly equal minimum backlash (difference < 0.001 mm), indicating concurrent contact. The bidirectional method shows overlapping ranges between \( \overset{\frown}{BC} \) and \( \overset{\frown}{CD} \) as well as between \( \overset{\frown}{BC} \) and \( \overset{\frown}{AB} \), confirming multi-point engagement. The unidirectional method displays no such overlap.

| Profile Segment Pair | Bidirectional Method Angular Range (°) | Unidirectional Method Angular Range (°) |

|---|---|---|

| Common Tangent (\( \overset{\frown}{BC} \)) and Concave Arc (\( \overset{\frown}{CD} \)) | 3.5 – 25.5 | None |

| Common Tangent (\( \overset{\frown}{BC} \)) and Convex Arc (\( \overset{\frown}{AB} \)) | 4.0 – 13.5 | None |

Finite element contact analysis is conducted to validate the backlash findings under load. A planar model of the strain wave gear is constructed, simplifying the wave generator as a cam contour, with the flexspline and circular spline modeled as gear rings. Contact pairs are established between the tooth profiles and between the flexspline and wave generator. A torque of 40 N·m is applied to the flexspline inner wall while fixing the circular spline and wave generator. The contact stress distribution on the flexspline tooth profile is extracted. The bidirectional design shows contact across a longer portion of the tooth flank, with distinct contact zones on both the concave and convex segments, corroborating multi-point engagement. The unidirectional design exhibits contact only on the convex arc. The maximum contact stresses are 44.175 MPa for the bidirectional method and 53.862 MPa for the unidirectional method, demonstrating a significant reduction in surface stress due to increased contact area.

The enhanced performance of the bidirectional conjugate method can be attributed to its holistic approach to conjugate geometry. By ensuring that the convex arc of the circular spline is conjugate with both arcs of the flexspline, the method maximizes the effective contact region and promotes favorable load distribution. This is particularly advantageous for strain wave gear applications in robotics and aerospace, where high precision and durability are paramount. The mathematical rigor of the envelope method, combined with iterative fitting, provides a robust framework for optimizing double-circular-arc profiles.

In terms of design efficiency, the bidirectional method reduces the number of preset parameters required, as the flexspline’s concave arc is derived through reverse conjugate calculation rather than empirical selection. This not only streamlines the design process but also mitigates the risk of human error. The method’s reliance on numerical solutions for the envelope equation makes it amenable to implementation in computer-aided design (CAD) software, facilitating automated profile generation for custom strain wave gear systems.

To further elucidate the mathematical principles, we delve into the details of the envelope condition and coordinate transformations. The transformation from flexspline to circular spline coordinates can be expressed in a compact form as:

$$

\mathbf{r}_2(\phi, s) = \mathbf{R}(\Phi) \mathbf{r}_1(s) + \mathbf{d}(\phi)

$$

where \( \mathbf{r}_1(s) = [x_1(s), y_1(s)]^T \) is the flexspline tooth profile vector, \( \mathbf{R}(\Phi) \) is the rotation matrix, and \( \mathbf{d}(\phi) = [\rho \sin\gamma, \rho \cos\gamma]^T \) is the translation vector. The envelope condition arises from the requirement that the relative velocity between the two tooth surfaces is orthogonal to the common normal at the contact point. For planar gearing, this reduces to the Jacobian determinant condition given earlier. Solving this condition numerically involves discretizing the parameter \( s \) and solving for \( \phi \) using root-finding algorithms such as Newton-Raphson method. The conjugate points are then computed as \( \mathbf{r}_2(\phi(s), s) \).

For the reverse conjugate calculation, the circular spline profile \( \mathbf{r}_2(s) \) is transformed back to the flexspline system using the inverse transformation:

$$

\mathbf{r}_{12}(\phi, s) = \mathbf{R}^{-1}(\Phi) (\mathbf{r}_2(s) – \mathbf{d}(\phi))

$$

Applying the envelope condition again yields the conjugate curve on the flexspline. The iterative nature of this bidirectional process ensures that the final profiles satisfy conjugacy constraints from both perspectives.

The fitting of discrete conjugate points to circular arcs is performed using least-squares minimization. For a set of points \( \{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^n \), we minimize the objective function:

$$

F(a, b, R) = \sum_{i=1}^n \left( \sqrt{(x_i – a)^2 + (y_i – b)^2} – R \right)^2

$$

where \( (a, b) \) is the circle center and \( R \) is the radius. Advanced optimization techniques can be employed to ensure that the fitted arcs maintain tangency conditions and avoid interference.

In practical applications, the design of strain wave gear systems must account for manufacturing tolerances, material properties, and operational conditions. The bidirectional conjugate method provides a foundation for developing high-performance tooth profiles that can be further refined through finite element analysis and experimental testing. The ability to achieve multi-point contact and reduced contact stress directly translates to improved longevity and reliability of strain wave gear drives.

In conclusion, the bidirectional conjugate design method for double-circular-arc tooth profiles represents a significant advancement in strain wave gear technology. By addressing the limitations of unidirectional conjugate approaches, it ensures full conjugate engagement across the entire tooth flank, promotes multi-point contact, and reduces contact stresses. The method’s mathematical robustness and reduced parameter dependency make it an attractive tool for engineers designing precision strain wave gear systems. Future work may explore extensions to three-dimensional profiling, dynamic load analysis, and integration with advanced manufacturing processes such as additive manufacturing. As strain wave gear continues to evolve, innovative design methodologies like the one presented here will play a crucial role in unlocking new levels of performance and efficiency.