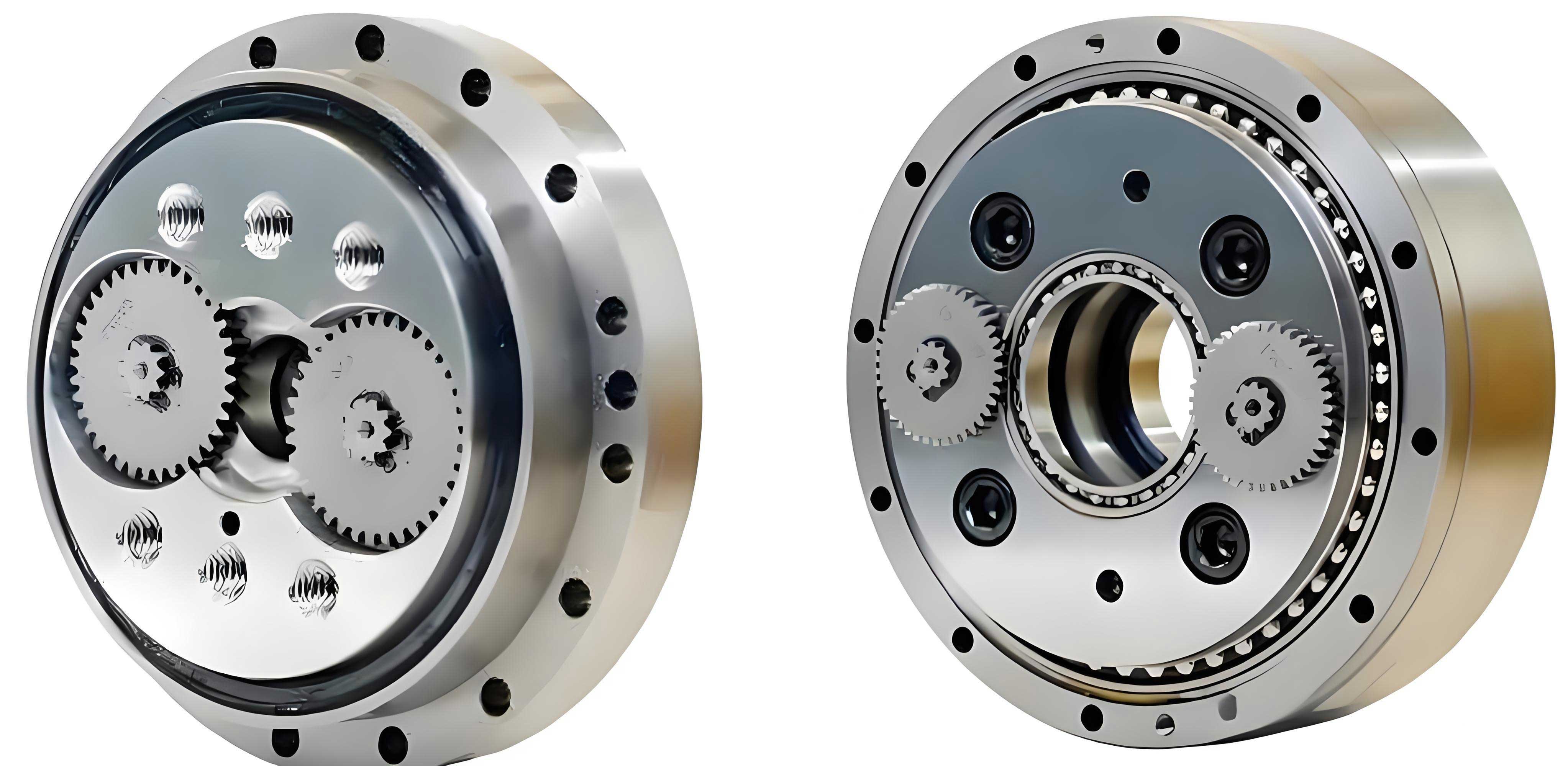

In the field of industrial robotics, the precision of motion control is paramount, and the RV reducer plays a critical role in ensuring high transmission accuracy, stability, and load capacity. As a key component, the performance of the RV reducer directly impacts the trajectory and efficiency of robotic operations. Transmission accuracy is one of the most scrutinized parameters, as it defines the positional fidelity of the output shaft relative to the input. However, geometric errors, such as coaxiality deviations between the input and output shafts, can significantly degrade this accuracy, yet they are often overlooked in existing models. Previous studies have focused on factors like tooth profile errors, backlash, and manufacturing tolerances, but a comprehensive model integrating coaxiality errors into the transmission chain remains underdeveloped. In this work, we address this gap by developing a coaxiality-transmission chain error vector model for the RV reducer, specifically targeting the RV-20E type. Our approach combines static analysis using ANSYS to quantify coaxiality errors under various torque conditions and dynamic simulation using ADAMS to validate the model and assess the impact of coaxiality on transmission precision. We aim to provide a robust framework that enhances the design and testing of RV reducer performance detection systems, ultimately contributing to higher standards in robotic actuation.

The foundation of our analysis lies in the transmission chain error vector model, which accounts for the torsional angle errors of key components along the motion path. For the RV reducer, the primary shafts include the sun gear shaft (input), planetary gear shafts, crankshafts, cycloidal gear shafts, and the pin gear shaft (output). Each component contributes to the overall transmission error when operational. We define the transmission error vector as the angular deviation at the output due to individual shaft torsions. For instance, the error vector from the input shaft torsional angle \(\theta_1^{\rightarrow}\) transmitted to the output is given by:

$$\theta_{11}^{\rightarrow} = \frac{1}{i_{16}} \theta_{1}^{\rightarrow}$$

where \(i_{16}\) is the transmission ratio of the RV reducer. Similarly, for two crankshafts with torsional angle \(\theta_2^{\rightarrow}\), the error vector is:

$$\theta_{22}^{\rightarrow} = \frac{2}{Z_4} \theta_{2}^{\rightarrow}$$

where \(Z_4\) is the number of teeth on the cycloidal gear. For the output disk with torsional angle \(\theta_4^{\rightarrow}\), the error vector is simply \(\theta_{44}^{\rightarrow} = \theta_{4}^{\rightarrow}\). For the pin gear shaft with 40 pins and torsional angle \(\theta_5^{\rightarrow}\), the error vector becomes:

$$\theta_{55}^{\rightarrow} = \frac{40Z_5}{Z_4} \theta_{5}^{\rightarrow}$$

where \(Z_5\) is the number of pin gear teeth. The total transmission chain error vector is the sum of these individual contributions:

$$\theta_{\text{total}}^{\rightarrow} = \theta_{11}^{\rightarrow} + \theta_{22}^{\rightarrow} + \theta_{44}^{\rightarrow} + \theta_{55}^{\rightarrow}$$

This model provides a baseline for understanding error propagation but does not account for coaxiality deviations. In practical testing setups, such as those using high-precision optical encoders, misalignment between the input and output shafts can introduce additional errors, compromising measurement accuracy. Therefore, we extend this model to include coaxiality errors.

Coaxiality error arises from radial tilt and displacement of shafts during operation. Considering the RV reducer as a multi-stage shaft system, we model the error when shafts are under steady rotation. The torque balance vector matrix for a shaft with radial tilt angle \(\beta\) and radial displacement \(a\) (input-output radial backlash deviation) is expressed as:

$$[ \vec{F}_1 \quad \vec{F}_2 \quad \ldots \quad \vec{F}_n ]

\begin{bmatrix}

\tan \beta \cdot \left( \frac{l_1}{2} + \frac{a}{\cos \beta} \right) + \frac{d_1}{2} \\

\tan \beta \cdot \left( \frac{l_2 + l_1}{2} + \frac{a}{\cos \beta} \right) + \frac{d_2}{2} \\

\vdots \\

\tan \beta \cdot \left( \frac{l_n + l_{n-1}}{2} + \frac{a}{\cos \beta} \right) + \frac{d_n}{2}

\end{bmatrix}^2 = 0$$

where \(\vec{F}_n\) is the average force on each shaft stage (in N), \(l_n\) is the total length of the n-th stage shaft (in mm), \(d_n\) is the outer diameter of the shafts (in m), and \(a\) is derived from standard tolerance tables (e.g., GB/T1800.1-2009). For the RV reducer with dimensions ≤500 mm, we adopt an IT3 grade, yielding \(a_{\text{input}} = 0.002 \, \text{mm}\) and \(a_{\text{output}} = 0.003 \, \text{mm}\). Integrating this into the error vector model, we derive expressions for each component. For the sun gear engagement (input shaft as a four-stage hollow shaft), the error vector becomes:

$$\theta_{11}^{\rightarrow}(F, \alpha, \beta) = \frac{7350}{i_{16}L}

\begin{bmatrix}

\frac{F_1 L_1}{d_1^4 \left(1 – \frac{d_{11}^4}{d_1^4}\right)} \\

\frac{F_2 L_2}{d_2^4 \left(1 – \frac{d_{22}^4}{d_2^4}\right)} \\

\frac{F_3 L_3}{d_3^4 \left(1 – \frac{d_{33}^4}{d_3^4}\right)} \\

\frac{F_4 L_4}{d_4^4 \left(1 – \frac{d_{44}^4}{d_4^4}\right)}

\end{bmatrix}

\cdot

\begin{bmatrix}

\tan \beta \cdot \left( \frac{l_1}{2} + \frac{a}{\cos \beta} \right) + \frac{d_1}{2} \\

\tan \beta \cdot \left( \frac{l_2 + l_1}{2} + \frac{a}{\cos \beta} \right) + \frac{d_2}{2} \\

\tan \beta \cdot \left( \frac{l_3 + l_2}{2} + \frac{a}{\cos \beta} \right) + \frac{d_3}{2} \\

\tan \beta \cdot \left( \frac{l_4 + l_3}{2} + \frac{a}{\cos \beta} \right) + \frac{d_4}{2}

\end{bmatrix}^2$$

For the planetary gear engagement (crankshaft as a seven-stage solid shaft, ignoring tilt error as an internal component), the error vector is:

$$\theta_{22}^{\rightarrow}(F) = \frac{7350}{Z_4 L}

\begin{bmatrix}

\frac{F_1}{d_1^3} & \frac{F_2}{d_2^3} & \frac{F_3}{d_3^3} & \frac{F_4}{d_4^3} & \frac{F_5}{d_5^3} & \frac{F_6}{d_6^3} & \frac{F_7}{d_7^3} & \frac{F_8}{d_8^3}

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

L_1 \\ L_2 \\ L_3 \\ L_4 \\ L_5 \\ L_6 \\ L_7 \\ L_8

\end{bmatrix}$$

For the cycloidal gear engagement (output disk as a three-stage solid shaft), the error vector is:

$$\theta_{44}^{\rightarrow}(F, \alpha, \beta) = \frac{7350}{L}

\begin{bmatrix}

\frac{F_1 L_1}{d_1^4} \\

\frac{F_2 L_2}{d_2^4} \\

\frac{F_3 L_3}{d_3^4}

\end{bmatrix}

\cdot

\begin{bmatrix}

\tan \beta \cdot \left( \frac{l_1}{2} + \frac{a}{\cos \beta} \right) + \frac{d_1}{2} \\

\tan \beta \cdot \left( \frac{l_2 + l_1}{2} + \frac{a}{\cos \beta} \right) + \frac{d_2}{2} \\

\tan \beta \cdot \left( \frac{l_3 + l_2}{2} + \frac{a}{\cos \beta} \right) + \frac{d_3}{2}

\end{bmatrix}^2$$

For the pin gear engagement (pin shaft as a solid smooth shaft, ignoring tilt error), the error vector is:

$$\theta_{55}^{\rightarrow}(\vec{F}) = \frac{20 Z_5 \vec{F}}{Z_4 d^3}$$

The total transmission chain error vector with coaxiality integration is then:

$$\theta_{\text{total}}^{\rightarrow} = \vec{\theta}_{11} + \vec{\theta}_{22} + \vec{\theta}_{44} + \vec{\theta}_{55}$$

This coaxiality-transmission chain error vector model forms the core of our analysis, allowing us to quantify how misalignment affects the RV reducer’s performance.

To obtain the coaxiality errors under operational conditions, we conducted static analysis using ANSYS software. The transmission system of the RV reducer performance detection device was simplified by removing non-essential parts like supports and bases, focusing on the core components: servo motor, coupling, RV reducer, torque sensor, and magnetic powder brake. Material properties were assigned based on equivalent mass conversion for non-mechanical parts and standard materials for mechanical parts. Key parameters are summarized in the following tables.

For non-mechanical parts, the material parameters are:

| Component | Material | Elastic Modulus (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Density (kg/m³) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Servo Motor | 40Gr | 2.12 × 10⁵ | 0.277 | 7870 |

| Torque Sensor | HT200 | 1.57 × 10⁵ | 0.270 | 7210 |

| RV Reducer | 40Gr | 2.12 × 10⁵ | 0.277 | 7870 |

| Magnetic Powder Brake | HT200 | 1.57 × 10⁵ | 0.270 | 7210 |

For mechanical parts, the material parameters are:

| Component | Material | Elastic Modulus (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Density (kg/m³) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaft | Q460 | 2.06 × 10⁵ | 0.280 | 7850 |

| Coupling | Q460 | 2.06 × 10⁵ | 0.280 | 7850 |

Boundary conditions were applied to simulate real-world loading. Forces and torques were set based on the torque sensor’s range, as shown below:

| Force Application Point | Force (N) |

|---|---|

| Servo Motor F1, -F1 | 250, -250 |

| Coupling F2 | -2.45 |

| Torque Sensor F3, -F3 | 50, -50 |

| RV Reducer F5, -F5 | 50, -50 |

| Magnetic Powder Brake F9, -F9 | 450, -450 |

Torque parameters for the input and output shafts were varied across a range:

| Shaft | Torque Range |

|---|---|

| Input Shaft T1 | 0.07 to 1.43 N·m |

| Output Shaft T2 | 10 to 200 N·m |

The ANSYS simulation provided cloud displacement paths in the Y-direction. For example, at T1 = 1.43 N·m and T2 = 200 N·m, the maximum cloud displacement values were extracted. The radial tilt angle \(\beta\) was calculated using:

$$\beta = \arcsin\left(\frac{Y}{L}\right)$$

where \(Y\) is the maximum cloud displacement in mm, and \(L\) is the shaft length (input L = 120 mm, output L = 160 mm). The results for different torque combinations are tabulated below, showing the coaxiality errors in terms of radial tilt angles.

| Input Torque (N·m) | Output Torque (N·m) | β_output (°) | Y_output (mm) | β_input (°) | Y_input (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.43 | 200 | 0.00153 | 0.0042594 | 0.0000288 | 0.000060295 |

| 1.35 | 190 | 0.00145 | 0.0040433 | 0.0000268 | 0.000056015 |

| 1.29 | 180 | 0.00137 | 0.0038271 | 0.0000252 | 0.000052804 |

| 1.21 | 170 | 0.00129 | 0.0036110 | 0.0000232 | 0.000048524 |

| 1.14 | 160 | 0.00122 | 0.0033948 | 0.0000214 | 0.000044779 |

| 1.07 | 150 | 0.00114 | 0.0031787 | 0.0000196 | 0.000041033 |

| 1.00 | 140 | 0.00106 | 0.0029625 | 0.0000178 | 0.000037288 |

| 0.93 | 130 | 0.000983 | 0.0027463 | 0.0000160 | 0.000033543 |

| 0.86 | 120 | 0.000906 | 0.0025302 | 0.0000142 | 0.000029797 |

| 0.79 | 110 | 0.000829 | 0.0023140 | 0.0000124 | 0.000026052 |

| 0.71 | 100 | 0.000751 | 0.0020979 | 0.0000104 | 0.000021772 |

| 0.64 | 90 | 0.000674 | 0.0018817 | 0.00000861 | 0.000018026 |

| 0.57 | 80 | 0.000596 | 0.0016656 | 0.00000682 | 0.000014281 |

| 0.50 | 70 | 0.000519 | 0.0014494 | 0.00000503 | 0.000010536 |

| 0.43 | 60 | 0.000442 | 0.0012332 | 0.00000324 | 0.0000067903 |

| 0.35 | 50 | 0.000364 | 0.0010171 | 0.00000120 | 0.0000025099 |

| 0.28 | 40 | 0.000287 | 0.00080093 | 0.00000059 | 0.0000012354 |

| 0.21 | 30 | 0.000209 | 0.00058477 | 0.00000238 | 0.0000049807 |

| 0.14 | 20 | 0.000132 | 0.00036861 | 0.00000417 | 0.0000087261 |

| 0.07 | 10 | 0.0000546 | 0.00015246 | 0.00000595 | 0.0000124710 |

These coaxiality error values serve as inputs for our dynamic simulations, enabling us to assess their impact on the transmission chain error of the RV reducer.

To validate the coaxiality-transmission chain error vector model, we performed dynamic simulations using ADAMS software. A 3D model of the RV-20E reducer was created and imported into ADAMS, with constraints applied to mimic real motion: planar joints for the input shaft and ground, cylindrical joints for crankshafts and bearings, and gear contacts for meshing components. The input speed was set to 1400 rpm, corresponding to an output speed of 10 rpm, simulating no-load conditions as per standard testing protocols. We first analyzed the model without coaxiality errors to establish a baseline. The torsional forces on key shafts were extracted from ADAMS simulations. For the input shaft (a four-stage hollow shaft), the torque curves for different stages were obtained; for instance, the first and third stages showed measurable forces, while the second stage had no contact. Similarly, for the crankshaft (a seven-stage solid shaft), forces on the second, fourth, sixth, and eighth stages were recorded. For the output disk (a three-stage solid shaft), forces on the first and second stages were noted. For the pin shaft (a solid smooth shaft), the torque was derived. Using these forces in our error vector model, we computed the individual error contributions. For example, the error from the sun gear engagement \(\theta_{11}^{\rightarrow}\) was calculated based on the input shaft torques and geometry. Assuming no coaxiality tilt, the values were minimal. The total transmission error was then derived as the vector sum. With clockwise rotation as positive, the total error was found to be:

$$\theta_{\text{total}} = \theta_{22} – \theta_{11} – \theta_{44} – \theta_{55} = 0.1020^\circ – 0.000138^\circ – 0.0147^\circ – 0.0815^\circ = 0.005662^\circ$$

This result was compared to the angle transmission error curve provided by a leading RV reducer manufacturer for no-load conditions, which indicates a maximum error of approximately 0.006389°. Since 0.005662° ≤ 0.006389°, our model aligns with empirical data, verifying its accuracy for the RV reducer within acceptable coaxiality limits.

Next, we investigated the effect of coaxiality errors beyond the permissible range. Using the tilt angles from the ANSYS analysis, we simulated various scenarios where the input and output shafts had radial misalignments. The transmission chain error was computed for each case, as summarized in the table below.

| Output Disk Radial Tilt Angle (°) | Input Shaft Radial Tilt Angle (°) | Transmission Chain Error (°) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0.005662 |

| 0.000519 | 0.00000503 | 0.0072 |

| 0.000596 | 0.00000682 | 0.0082 |

| 0.000674 | 0.00000861 | 0.0198 |

| 0.000751 | 0.0000104 | 0.0213 |

| 0.000829 | 0.0000124 | 0.0395 |

| 0.000906 | 0.0000142 | 0.1457 |

| 0.000983 | 0.0000160 | 0.1511 |

| 0.00106 | 0.0000178 | 0.0131 |

| 0.00114 | 0.0000196 | 0.0232 |

| 0.00122 | 0.0000214 | 0.0432 |

| 0.00129 | 0.0000232 | 0.0385 |

| 0.00137 | 0.0000252 | 0.0603 |

| 0.00145 | 0.0000268 | 0.0870 |

| 0.00153 | 0.0000288 | 0.0963 |

The data reveals that when coaxiality exceeds allowable limits, the transmission error does not increase linearly but fluctuates, likely due to uneven friction distribution along the shafts. Notably, at an input shaft tilt angle of 0.0000160°, the error peaks at 0.1511°, which is over 26 times the baseline error. Such deviations can accelerate wear in the RV reducer and compromise the accuracy of optical encoder measurements, severely reducing the reliability of performance detection systems. This underscores the importance of coaxiality adjustment mechanisms in RV reducer testing setups, as even minor misalignments can lead to significant precision loss.

In conclusion, we have developed a coaxiality-transmission chain error vector model for the RV reducer, integrating geometric misalignments into the error analysis. Through static simulations with ANSYS, we quantified coaxiality errors under varying torque conditions, and via dynamic simulations with ADAMS, we validated the model against standard no-load data, confirming its accuracy with a transmission error of 0.005662° within permissible coaxiality ranges. Our analysis further demonstrates that coaxiality errors beyond tolerance can drastically affect transmission precision, with errors reaching up to 0.1511°, highlighting their critical role in RV reducer performance. This work provides a theoretical foundation for designing coaxiality adjustment mechanisms in RV reducer testing devices, offering practical insights for enhancing detection accuracy. Future research could expand this model to include other geometric errors, such as parallelism or perpendicularity deviations, and explore real-time compensation strategies. As the demand for high-precision robotics grows, such models will be invaluable for standardizing RV reducer evaluation and ensuring optimal performance in industrial applications.