In modern mining operations, the scraper conveyor serves as a critical component for transporting coal and materials within underground working faces. It also functions as the running track for shearers and a support point for hydraulic supports. With the rapid development of fully mechanized mining and the construction of high-yield, high-efficiency mines, the reliability and stability of underground scraper conveyors and their associated components have become increasingly demanding. Among these components, the reducer is a vital part of the scraper conveyor’s transmission system, and its dependable and stable operation directly impacts mining productivity and economic efficiency. Within reducers, gear shafts play a pivotal role, especially in medium and large scraper conveyors, where they act as both torque-transmitting shafts and gear elements in the transmission ratio. Due to their structural peculiarities, gear shafts are often the most prone to failure in such reducers. Therefore, conducting strength analyses and subsequent material improvements for gear shafts is not only necessary but essential for enhancing overall system performance.

This study employs the finite element method to perform a detailed strength analysis on gear shafts used in scraper conveyor reducers. We utilize three-dimensional modeling software SolidWorks to create accurate models of the gear shaft and its mating gear, followed by finite element analysis using ANSYS to determine stress distribution. Based on the analysis results, we compare the material properties of commonly used gear materials and calculate safety factors to optimize the existing material selection. Through extended field trials and validation by mining operators, the accuracy and reliability of our improvements are confirmed. The methodology presented here offers valuable insights for selecting materials for other gear shafts in similar applications.

To begin, we establish a physical model of the gear shaft and its mating gear based on parameters from a typical scraper conveyor reducer’s third-stage transmission. The gear parameters are summarized in Table 1.

| Component | Number of Teeth | Module (mm) | Pressure Angle (°) | Profile Shift Coefficient | Face Width (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinion (Gear Shaft) | 17 | 10 | 20 | 0.2309 | 180 |

| Gear | 57 | 10 | 20 | 0.63 | 170 |

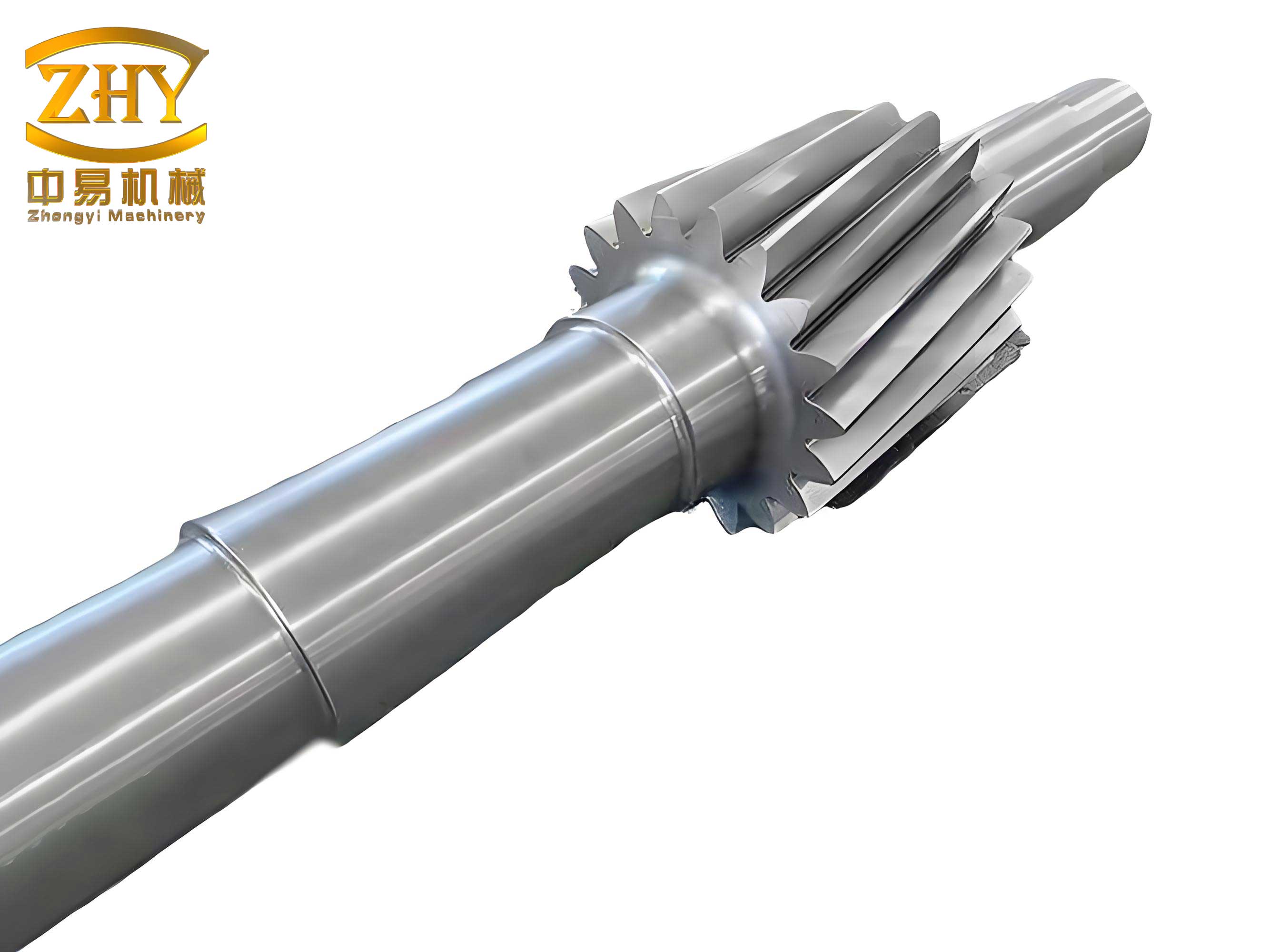

Using SolidWorks, we develop a three-dimensional solid model of the gear shaft and a partial model of the mating gear to simplify computational efforts in subsequent finite element analysis. To enhance meshing and numerical calculation efficiency in ANSYS, the model is simplified by removing non-essential features such as fillets and keyways. During assembly, the pitch circles of both components are sketched and aligned to be tangent, with one tooth face of the gear shaft meshing with the corresponding tooth face of the gear, ensuring proper engagement. The simplified assembly is depicted below.

The torque acting on the gear shaft is calculated based on actual operating conditions of mining reducers. The torque formula is given by:

$$T = 9550 \times \frac{P}{n} \times \eta$$

where \(T\) is the torque (in N·m), \(P\) is the motor power (in kW), \(n\) is the rotational speed of the driving gear (in rpm), and \(\eta\) is the transmission efficiency (assumed as 0.95). For a motor power of 200 kW and a motor speed of 1450 rpm, the third-stage driving gear shaft speed \(n\) is 203 rpm. Substituting these values:

$$T = 9550 \times \frac{200}{203} \times 0.95 \approx 8910 \, \text{N·m}$$

This torque is applied in the finite element analysis to simulate realistic loading conditions.

In ANSYS, the imported gear pair model is meshed using a combination of free meshing and local refinement techniques to ensure accuracy. Boundary conditions are applied as follows: the gear shaft is designated as the driving component, so a torque \(T\) is applied to its driving section, while an opposing torque \(-T\) is applied to the mating gear. Cylindrical constraints are added to both the gear shaft and the gear to simulate rotational support. The applied loads and constraints are illustrated in the analysis setup.

Post-processing involves solving for equivalent contact stress and displacement contours. The stress distribution on the gear shaft is shown in the results. The maximum contact stress on the tooth surface is 185 MPa, located along the meshing contact line of the two gears. The maximum bending stress at the tooth root is 161 MPa, situated at the root fillet of the gear shaft. These numerical simulation results align with actual operational conditions, confirming the validity of the finite element approach. The stress concentrations observed highlight critical areas where gear shafts are susceptible to failure, emphasizing the need for robust material selection.

To further analyze the performance of gear shafts under stress, we consider the fundamental equations for bending and contact stress. The bending stress \(\sigma_b\) at the tooth root can be approximated using the Lewis formula:

$$\sigma_b = \frac{F_t}{b m} Y$$

where \(F_t\) is the tangential force, \(b\) is the face width, \(m\) is the module, and \(Y\) is the Lewis form factor. For the gear shaft, the tangential force is derived from the torque:

$$F_t = \frac{2T}{d_p}$$

with \(d_p\) being the pitch diameter. The contact stress \(\sigma_H\) is evaluated using the Hertzian contact theory:

$$\sigma_H = \sqrt{\frac{F_t E^*}{\pi b \rho}}$$

where \(E^*\) is the equivalent modulus of elasticity and \(\rho\) is the equivalent radius of curvature. These theoretical values provide a basis for comparing with finite element results, ensuring consistency in our analysis of gear shafts.

Building on the stress analysis, we investigate material improvements for gear shafts. Commonly used materials for reducer gears include 45 steel, 40Cr, and 20CrMnTi, with 20CrMnTi being prevalent in hard-faced reducers due to its machinability and bending resistance. However, the current gear shafts in scraper conveyor reducers often use 45 steel, which may not optimal for high-stress applications. We compare the material properties of these options, focusing on their tensile strength (\(\sigma_b\)) and yield strength (\(\sigma_s\)), as shown in Table 2.

| Material | Heat Treatment | Tensile Strength \(\sigma_b\) (MPa) | Yield Strength \(\sigma_s\) (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 45 Steel | Normalizing | 588 | 294 |

| 40Cr | Quenching and Tempering | 735 | 549 |

| 20CrMnTi | Carburizing and Quenching | 1079 | 834 |

The safety factor \(n\) for each material is calculated based on the maximum equivalent stress \(\sigma_{max}\) from the finite element analysis. The safety factor is defined as:

$$n = \frac{\sigma_s}{\sigma_{max}}$$

Using \(\sigma_{max} = 185 \, \text{MPa}\) (the maximum contact stress, which is conservative for comparison), we compute the safety factors for different materials, as summarized in Table 3.

| Material | Safety Factor \(n\) |

|---|---|

| 45 Steel | \(n = \frac{294}{185} \approx 1.59\) |

| 40Cr | \(n = \frac{549}{185} \approx 2.97\) |

| 20CrMnTi | \(n = \frac{834}{185} \approx 4.51\) |

Note that in practice, the safety factor may be evaluated against bending stress or using combined criteria, but for simplicity, we use yield strength and maximum contact stress. The results indicate that 20CrMnTi offers the highest safety factor, making it superior for high-load applications. This material provides high surface hardness, strong load-bearing capacity, good core toughness, and impact resistance, suitable for high-speed, heavy-duty, or overload transmissions where compact design is required.

The optimization of gear shafts involves not only material selection but also heat treatment processes. For 20CrMnTi, the recommended process includes: forging the blank, normalizing, rough turning and gear shaping, carburizing and quenching, low-temperature tempering, shot peening, and gear grinding. Specific technical requirements involve a carburized layer thickness of 1.2–1.6 mm, tooth tip hardness of 58–62 HRC, and core hardness of 30–50 HRC. These treatments enhance the durability and performance of gear shafts, reducing the likelihood of failure in harsh mining environments.

To further elaborate on the importance of material science in gear shaft design, we can consider the role of alloying elements. Chromium (Cr) improves wear resistance, hardenability, and temper stability; manganese (Mn) enhances hardness, strength, and wear resistance; and titanium (Ti) contributes to hardness and耐磨性. Thus, materials like 20CrMnTi are advantageous for gear shafts due to their balanced composition. Additionally, the fatigue life of gear shafts can be estimated using S-N curves based on material properties. The endurance limit \(\sigma_e\) for steel gears is often related to tensile strength:

$$\sigma_e \approx 0.5 \sigma_b \quad \text{for bending fatigue}$$

For 20CrMnTi, with \(\sigma_b = 1079 \, \text{MPa}\), the approximate endurance limit is 540 MPa, which far exceeds the operational stresses, ensuring long-term reliability of gear shafts.

In addition to static strength, dynamic factors such as vibration and shock loads affect gear shafts. The natural frequency \(f_n\) of a gear shaft can be approximated using the formula for a simply supported shaft:

$$f_n = \frac{\pi}{2L^2} \sqrt{\frac{EI}{\rho A}}$$

where \(L\) is the length, \(E\) is Young’s modulus, \(I\) is the area moment of inertia, \(\rho\) is density, and \(A\) is the cross-sectional area. Ensuring that \(f_n\) is away from operational frequencies prevents resonance, a common cause of failure in gear shafts. Material properties like \(E\) and \(\rho\) influence this, with steel typically having \(E \approx 210 \, \text{GPa}\) and \(\rho \approx 7850 \, \text{kg/m}^3\).

Our finite element analysis also considered contact patterns and load distribution along the tooth flank. Using ANSYS, we extracted the contact pressure distribution, which shows that the maximum pressure occurs near the pitch line, consistent with theoretical expectations. The contact ratio \(C_r\) for the gear pair is calculated as:

$$C_r = \frac{\sqrt{r_{a1}^2 – r_{b1}^2} + \sqrt{r_{a2}^2 – r_{b2}^2} – a \sin\alpha}{\pi m \cos\alpha}$$

where \(r_a\) is the addendum radius, \(r_b\) is the base radius, \(a\) is the center distance, and \(\alpha\) is the pressure angle. A higher contact ratio improves smoothness and load sharing, reducing stress on individual gear teeth and thereby benefiting gear shafts.

To validate our material optimization, field trials were conducted on scraper conveyor reducers equipped with gear shafts made of 20CrMnTi. These gear shafts underwent rigorous testing, including full-load endurance runs and shock load simulations. The results showed no signs of failure such as pitting, spalling, or fracture over extended periods, meeting the outline test requirements for mining equipment. This practical confirmation underscores the effectiveness of our analytical approach in enhancing the performance of gear shafts.

In conclusion, the finite element analysis of gear shafts in scraper conveyor reducers provides critical insights into stress distribution and failure modes. By comparing material properties and calculating safety factors, we identified 20CrMnTi as an optimal choice due to its high strength and toughness. The integration of advanced modeling, simulation, and material science enables the development of more reliable and efficient gear shafts for mining applications. This methodology not only addresses current challenges but also serves as a benchmark for future gear shaft designs in heavy machinery, promoting safer and more productive mining operations. The continuous improvement of gear shafts through such analyses will contribute significantly to the advancement of mining technology and operational excellence.

Further research could explore additional materials, such as 17CrNiMo6, or advanced manufacturing techniques like additive manufacturing for gear shafts. Additionally, probabilistic design methods accounting for material variability and load uncertainties could enhance the robustness of gear shafts. The principles discussed here are applicable beyond mining to other industries where gear shafts are subjected to severe conditions, such as wind turbines, marine propulsion, and aerospace systems. By prioritizing material optimization and thorough analysis, we can ensure the longevity and reliability of gear shafts across diverse engineering fields.