In my extensive career focusing on advanced gear manufacturing, I have consistently encountered the critical role of heat treatment in defining the performance and longevity of gears made from Cr-Ni-Mo series steels. These alloys, including grades like 17CrNiMo6, 17Cr2Ni2Mo, 18CrNiMo7-6, 20CrNi2Mo, 20CrNiMo, and 20Cr2Ni4A, are selected for applications demanding exceptional strength, toughness, and wear resistance—from heavy-duty truck drive axles to colossal industrial gearboxes in mining and energy sectors. However, the very properties that make these steels excellent also render their heat treatment extraordinarily complex. A slight misstep in process control can precipitate a host of heat treatment defects, such as excessive retained austenite, coarse carbide networks, unacceptable distortion, quenching cracks, and inadequate case depth. This article, drawn from my hands-on experience, provides a detailed examination of the tailored heat treatment processes for these steels, integrating tables and formulas to summarize key parameters, while continually underscoring the imperative of defect mitigation.

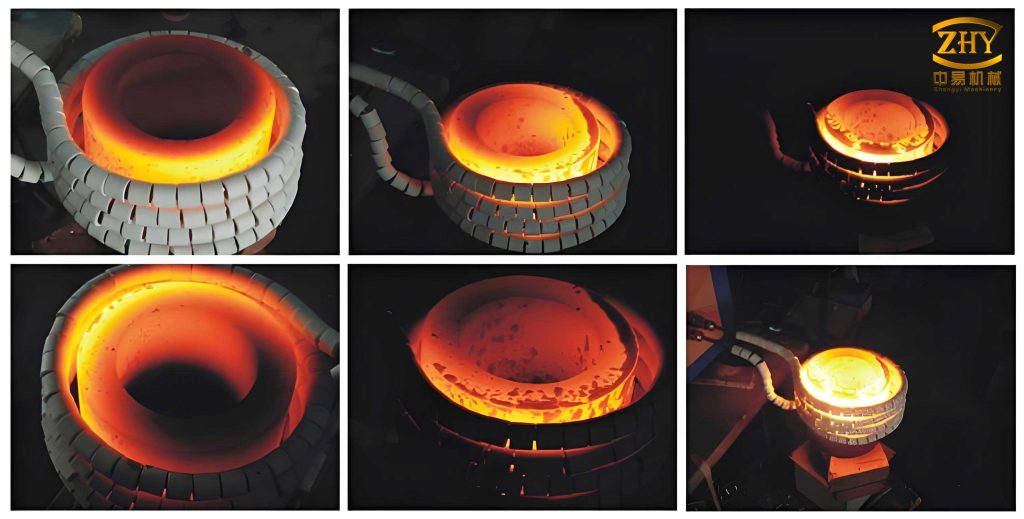

The visual aspect of gear heat treatment is crucial for appreciating the microstructural transformations. Below is an image that captures the essence of this intricate process.

Cr-Ni-Mo steels derive their prowess from a balanced composition of chromium, nickel, and molybdenum, which imparts high hardenability and core toughness. The primary heat treatment sequence invariably involves carburizing to create a hard, wear-resistant surface, followed by quenching and tempering. Yet, each steel grade necessitates specific modifications to this sequence to address its unique metallurgical behavior and the stringent requirements of the final gear application. A universal challenge is managing the high nickel content, which, while boosting toughness, can lead to higher levels of retained austenite after quenching—a prominent heat treatment defect that softens the surface and reduces fatigue life. Therefore, processes often incorporate double quenching, intermediate cooling, or specific tempering cycles to transform this austenite.

Heat Treatment of 17CrNiMo6 Steel Gears

I frequently specify 17CrNiMo6 steel for heavy-duty automotive spiral bevel gears. Its processing begins with a preparatory isothermal normalizing of the forging blank to ensure a uniform, machinable structure of ferrite and pearlite, thus preventing later machining issues—a preemptive strike against heat treatment defects originating from inhomogeneous starting material. The core carburizing and quenching process, often conducted in continuous furnaces, must be precisely calibrated.

| Zone | 1 (Heating) | 2 (Soaking) | 3 (Carburizing) | 4 (Diffusion) | 5 (Diffusion) | Intermediate Cool | Reheat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | 880 | 910 | 920 | 910 | 900 | 550 | 840 |

| Carbon Potential (%) | — | — | 1.15 | 1.00 | 0.90 | — | 0.80 |

| Time (min per tray) | 60 | 60 | 150 | 150 | 60 | Variable | 150 |

The intermediate cooling step to 550°C before reheating and quenching is vital for reducing distortion and refining the austenite grain size, directly countering distortion-related heat treatment defects. For very high-toughness requirements, a carburize-quench-temper-quench-temper sequence is employed. The effective case depth (ECD) can be estimated using a simplified diffusion equation:

$$ECD = k \sqrt{t}$$

where \( k \) is a temperature-dependent diffusion coefficient and \( t \) is the effective carburizing time. For 17CrNiMo6 at 920°C, \( k \) is approximately 0.5 mm/√h. Improper control here can lead to shallow case depth, a critical heat treatment defect causing premature pitting failure.

Heat Treatment of 17Cr2Ni2Mo Steel Gears

My work with mining machinery gears made from 17Cr2Ni2Mo steel involves deep case hardening. The preparatory treatment is a double cycle of normalizing and high-temperature tempering to stabilize the structure. The carburizing process for deep cases (e.g., 3-5 mm) requires a multi-stage carbon potential profile to avoid excessive surface carbides, another common heat treatment defect.

| Process Step | Temperature (°C) | Key Parameters | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Normalizing | 950-1150 | Air cool | Homogenization |

| High-Temp Tempering | 650-700 | 4 hours minimum | Stress relief, machinability |

| Carburizing (Strong) | 880-890 | CP=1.2-1.3%, 50h | Build carbon gradient |

| Carburizing (Diffusion I) | 930 | CP=0.9%, 12h | Lower surface carbon |

| Carburizing (Diffusion II/III) | 930 | CP=0.85%, 56h each | Achieve target depth |

| Final Quench | 800-820 | Oil quench to 160-200°C | Harden with low stress |

| Low-Temp Tempering | 180-200 | 2.6 h/mm thickness | Relieve stresses, attain hardness |

To manage distortion—a costly heat treatment defect—I recommend controlled quenching into hot oil (80-100°C) and interrupting cooling at 160-180°C, followed by an isothermal hold. The surface hardness (HV) after treatment can be related to the tempering temperature (T in Kelvin) and time (t in hours) via an empirical Hollomon-Jaffe parameter:

$$P = T(C + \log t)$$

where C is a material constant. Deviations from the optimal P value lead to undesirable hardness loss or embrittlement.

Heat Treatment of 18CrNiMo7-6 and 20CrNi2Mo Steel Gears

For high-speed, high-load gears in wind turbine gearboxes, I utilize 18CrNiMo7-6 and 20CrNi2Mo steels. Their high nickel content demands even tighter carbon potential control during carburizing to keep surface carbides and retained austenite within limits—both are detrimental heat treatment defects if excessive.

| Steel Grade | Strong Carburizing | Diffusion | Final Carbon Potential before Quench | Resulting Case Depth (550 HV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18CrNiMo7-6 | 930°C, CP=1.05%, 20h | 930°C, CP=0.80%, 10h | 0.73% | ~2.8 mm |

| 20CrNi2Mo | 930°C, CP=1.25%, 20h | 930°C, CP=0.90%, 10h | 0.73% | ~2.91 mm |

The quenching process often involves a direct quench from the carburizing temperature for 20CrNi2Mo, but for 18CrNiMo7-6, a reheat quench is sometimes preferred to refine the core microstructure. The amount of retained austenite (RA) can be approximated by a formula considering surface carbon content (C_s) and quenching temperature (T_q):

$$RA(\%) \approx k_1 \cdot C_s + k_2 \cdot (M_s – T_q)$$

where \( M_s \) is the martensite start temperature, and \( k_1, k_2 \) are coefficients. Exceeding 20-25% RA is considered a heat treatment defect, necessitating sub-zero treatment or high-temperature tempering for correction.

Heat Treatment of 20CrNiMo Steel Gears

In the mass production of automotive differential gears from 20CrNiMo steel, my focus is on process stability in continuous furnaces. Isothermal normalizing of forgings is critical to prevent banded structures that can cause uneven hardening—a subtle but serious heat treatment defect.

| Furnace Zone | Temperature (°C) | Carbon Potential (%) | Atmosphere Flow (RX, m³/h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heating | 900 | — | 8 |

| Soaking | 930 | 1.25 | 10 |

| Carburizing I | 930 | 1.20 | 14 |

| Carburizing II | 930 | 0.85 | 14 |

| Diffusion/Quench Prep | 850 | 0.80 | 19 |

The final hardness gradient is paramount. The core hardness (H_c) should be maintained between 35-45 HRC to support the case. A common defect is soft core due to inadequate hardenability or improper quenching, which I address by ensuring the ideal critical diameter \( D_c \) is met:

$$D_c = f(Mn, Cr, Ni, Mo, \text{quenchant severity})$$

Calculating \( D_c \) ensures the gear section fully transforms to martensite at the core, avoiding the heat treatment defect of ferrite or bainite formation.

Heat Treatment of 20Cr2Ni4A Steel Gears

For ultra-high-strength applications like tank transmissions, I employ 20Cr2Ni4A steel with carbonitriding. The “three-stage control” process involves a lower temperature (e.g., 850°C) to limit distortion and control compound layer formation. The key is to balance carbon and nitrogen potentials to avoid brittle chromium carbonitrides at the grain boundaries, a catastrophic heat treatment defect that drastically reduces impact toughness. The effective case depth in carbonitriding grows according to a modified law:

$$d_{CN} = k_{CN} \sqrt{t}$$

where \( k_{CN} \) is higher than for carburizing alone due to nitrogen’s accelerating effect on diffusion.

Common Heat Treatment Defects and Mitigation Formulas

Throughout my practice, I have systematized the understanding and prevention of heat treatment defects. Below is a consolidated summary linking defects, their causes, and quantitative control measures.

| Defect Type | Primary Cause | Preventive/Corrective Action | Quantitative Check |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excessive Retained Austenite | High surface carbon, high Ni, slow quench | Post-quench deep freeze, high-temp temper, double quench | RA % < 25 (by XRD). Control via: $$C_s < 0.85\%$$ |

| Coarse or Network Carbides | Excessive carbon potential during boost phase | Lower boost CP, extend diffusion time | Carbide rating ≤ 3 (per ASTM). Ensure: $$CP_{boost} \cdot t_{boost} \leq K_{carb}$$ |

| Distortion & Cracking | Thermal & transformation stresses, non-uniform cooling | Isothermal pre-treatment, hot oil/quench interruption, press quenching | Minimize stress (\(\sigma\)): $$\sigma \propto E \cdot \alpha \cdot \Delta T \cdot f_{phase}$$ |

| Insufficient Case Depth | Low temperature, short time, low carbon potential | Increase time/temperature per diffusion equation | Verify ECD: $$ECD_{measured} \geq k\sqrt{t_{eff}}$$ |

| Soft Spots or Low Surface Hardness | Surface oxidation, inadequate quenching, high RA | Use protective atmosphere, optimize quenchant agitation and temperature | Surface hardness ≥ 58 HRC. Correlate quench rate (V_q) to hardness: $$HV = A + B \log(V_q)$$ |

The interplay of time, temperature, and carbon potential is best managed using computational models that solve the diffusion equation for carbon in austenite:

$$\frac{\partial C}{\partial t} = D(T) \frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial x^2}$$

where \( D(T) = D_0 \exp(-Q/RT) \) is the temperature-dependent diffusion coefficient. Modern furnace controllers use this principle to dynamically adjust carbon potential, thereby proactively preventing gradient-related heat treatment defects.

Furthermore, the hardenability of these steels is quantified using ideal critical diameter (D_I) calculations based on the Grossmann method, incorporating multiplying factors for each alloying element. Failure to account for this can lead to the heat treatment defect of insufficient core hardness in large-section gears.

Conclusion

In summary, the heat treatment of Cr-Ni-Mo series steel gears is a sophisticated balancing act between achieving supreme surface hardness and core toughness while vigilantly avoiding an array of potential heat treatment defects. From my experience, success hinges on a foundation of proper preparatory heat treatment, followed by meticulously controlled carburizing or carbonitriding cycles with staged carbon potentials, and concluding with a quenching and tempering regimen tailored to the specific steel’s transformation characteristics. The use of intermediate cooling, double quenching, and precise tempering are not just optional refinements but essential strategies to combat defects like retained austenite and distortion. By employing the empirical formulas and tabulated parameters discussed herein—and understanding the underlying diffusion and transformation kinetics—engineers can significantly enhance process reliability. Ultimately, continuous monitoring and adaptation of these heat treatment protocols are the keys to manufacturing gears that meet the extreme demands of modern machinery, ensuring performance, durability, and safety while minimizing the occurrence of costly heat treatment defects.