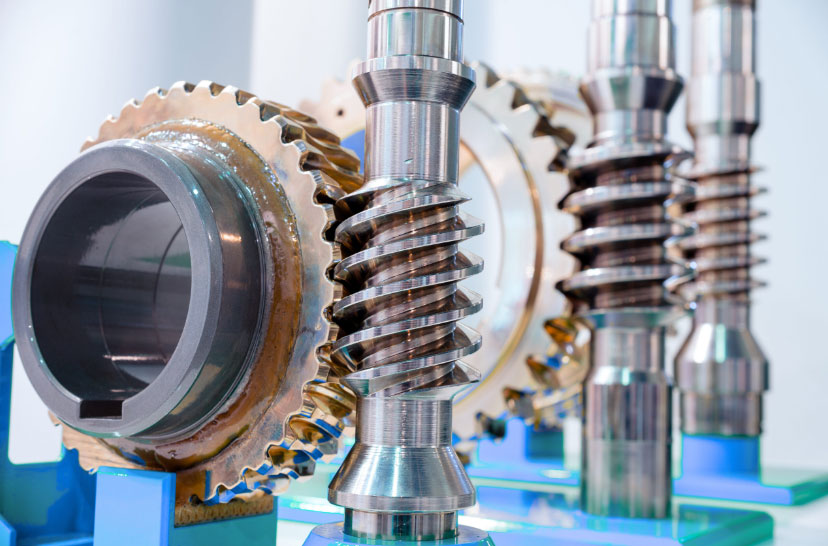

Double-enveloping worm-gear drives represent a sophisticated class of power transmission components characterized by their extended contact area and high torque capacity. Unlike standard cylindrical worm-gears, both the worm thread and the gear tooth surfaces are generated via an enveloping process, leading to a theoretically line contact that can enhance load distribution. However, this complex geometry presents significant challenges in design, manufacturing, and quality control, making it sensitive to errors and traditionally difficult to optimize. Modern computational methods provide the tools necessary to unify the design process, perform detailed geometrical analysis, and implement precise measurement protocols. This article details a comprehensive computerized approach to the design and analysis of the two predominant types of double-enveloping worm-gears, integrating state-of-the-art techniques for curvature analysis, tooth contact simulation, and coordinate measurement.

The core challenge in designing double-enveloping worm-gears lies in managing their intricate geometry. Two primary manufacturing setups exist in industry for generating the worm thread surface: one where the worm axis is orthogonal to the machine table axis during cutting, and another where these axes are intentionally set non-orthogonal. A robust modern design system must encapsulate both models within a single, flexible computational framework. This framework should not only generate the conjugate surfaces but also analyze critical performance indicators such as undercutting boundaries, relative curvatures, contact patterns, sliding velocities, and contact ratios, ultimately guiding the design towards optimal load-carrying capacity and efficiency.

1. Tool Surfaces and Machine Tool Synthesis

The generation of the worm helical surface begins with a defining tool surface. For double-enveloping worm-gears, common tool forms include a plane, a cone, a torus, or a finger-shaped cone. The plane is the most frequently employed due to its simplicity. The spatial relationship between the cutting tool and the blank worm defines the resulting geometry. The two classic setups can be synthesized into a generalized model. Let us define a coordinate system attached to the machine table as \( S_c(O_c-x_c, y_c, z_c) \), where the tool is fixed, and a system attached to the worm as \( S_h(O_h-x_h, y_h, z_h) \). The worm axis is aligned with \( y_h \). The generalized setup involves two angles: the tilt angle \(\beta\) of the tool middle plane relative to the table axis, and the offset angle \(\delta\) between the worm axis \(y_h\) and the table axis \(z_c\).

The orthogonal-axis model is obtained by setting \(\delta = 0\) and \(\beta = \lambda\), where \(\lambda\) is the lead angle at the worm pitch cylinder midpoint. The non-orthogonal-axis model is obtained by setting \(\beta = 0\) and \(\delta = \lambda\). This synthesis allows for a unified mathematical treatment and computer program capable of handling both types of double-enveloping worm-gears, including designs with corrective modifications.

2. Mathematical Foundation: Coordinate Transformations

The modern design of worm-gears relies heavily on matrix algebra for describing spatial relationships and motions. We use \(3 \times 3\) orthogonal coordinate transformation matrices as the fundamental tool. These matrices are clear in meaning and convenient for programming. The basic rotation matrices about the principal axes are:

$$

\mathbf{L}_x(\alpha) = \begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & \cos\alpha & \sin\alpha \\

0 & -\sin\alpha & \cos\alpha

\end{bmatrix}, \quad

\mathbf{L}_y(\beta) = \begin{bmatrix}

\cos\beta & 0 & -\sin\beta \\

0 & 1 & 0 \\

\sin\beta & 0 & \cos\beta

\end{bmatrix}, \quad

\mathbf{L}_z(\gamma) = \begin{bmatrix}

\cos\gamma & \sin\gamma & 0 \\

-\sin\gamma & \cos\gamma & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

$$

The unit vectors along the coordinate axes are denoted as:

$$

\mathbf{i} = (1, 0, 0)^T, \quad \mathbf{j} = (0, 1, 0)^T, \quad \mathbf{k} = (0, 0, 1)^T

$$

These matrices and vectors are used extensively to define the position and orientation of the tool, the worm, and the gear throughout the generation process.

3. Generation of the Worm (or Hob) Helical Surface

The worm thread surface is generated as the envelope of the tool surface family. Consider a planar tool as an example. In a coordinate system \(S_p\) attached to the tool, the plane and its unit normal can be defined by parameters \(x_p\) and \(z_p\):

$$

\mathbf{r}^{(p)} = (x_p, 0, z_p)^T, \quad \mathbf{n}^{(p)} = -\mathbf{j}

$$

This surface is then positioned in the machine table system \(S_c\) through transformations involving the tilt angle \(\beta\) and a positioning angle \(\alpha_N\). The family of tool surfaces in the worm coordinate system \(S_h\) is created by introducing the worm rotation \(\phi_h\) and the offset \(\delta\):

$$

\mathbf{r}^{(h)} = \mathbf{L}_y(-\phi_h) \mathbf{L}_x(-\delta) [\mathbf{L}_z(\phi_c) \mathbf{r}^{(c)} + E_{ch} \mathbf{i}]

$$

Here, \(E_{ch}\) is the center distance during worm cutting, and \(\phi_c\) is the table rotation angle, related to \(\phi_h\) by the machining ratio \(c_{cw} = N_c / N_w\), where \(N_c\) is the imaginary tooth number of the tool and \(N_w\) is the number of worm threads.

The key to finding the envelope is the equation of meshing, which states that the relative velocity between the tool and the worm at a point of contact must be orthogonal to the common surface normal. The relative velocity \(\mathbf{v}_p^{(ch)}\) in the tool system \(S_p\) is derived from the angular velocities \(\boldsymbol{\omega}_p^{(c)}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\omega}_p^{(h)}\):

$$

\mathbf{v}_p^{(ch)} = (\boldsymbol{\omega}_p^{(ch)} \times \mathbf{r}’_p) – \boldsymbol{\omega}_p^{(h)} \times \mathbf{E}_{ch}

$$

where \(\boldsymbol{\omega}_p^{(ch)} = \boldsymbol{\omega}_p^{(c)} – \boldsymbol{\omega}_p^{(h)}\). The equation of meshing is:

$$

f(x_p, z_p, \phi_c) = \mathbf{v}_p^{(ch)} \cdot \mathbf{n}_p = (\boldsymbol{\omega}_p^{(ch)} \times \mathbf{r}’_p) \cdot \mathbf{n}_p – (\boldsymbol{\omega}_p^{(h)} \times \mathbf{E}_{ch}) \cdot \mathbf{n}_p = 0

$$

For a plane, this can be solved explicitly for \(z_p\). The worm helical surface \(\Sigma_h\) is defined by the system:

$$

\Sigma_h: \begin{cases}

\mathbf{r}^{(h)} = \mathbf{L}_y(-\phi_h) \mathbf{L}_x(-\delta) [\mathbf{L}_z(\phi_c) \mathbf{r}^{(c)} + E_{ch} \mathbf{i}] \\

f(x_p, z_p, \phi_c) = 0

\end{cases}

$$

By assigning a fixed value to \(\phi_c\) and solving for points satisfying \(f=0\), we obtain an instantaneous contact line on the worm. The totality of these lines for varying \(\phi_c\) forms the worm thread surface. This surface subsequently serves as the hob surface for generating the worm wheel.

4. Generation of the Worm Wheel Tooth Surface

The worm wheel tooth surface is generated as the envelope of the hob helical surface family. The coordinate systems are now set with the hob (identical to the worm) in system \(S_h\) and the wheel blank in system \(S_g\). The hob rotates with angular velocity \(\boldsymbol{\omega}^{(h)} = c_{gh} \mathbf{j}\), where \(c_{gh} = N_g / N_h\) is the gear ratio (wheel teeth over worm threads). The wheel rotates with \(\boldsymbol{\omega}^{(g)} = \mathbf{L}_y(-\phi’_h + \psi_h) \mathbf{k}\), where \(\psi_h\) is the hob rotation angle and \(\phi’_h\) is the surface parameter analogous to \(\phi_h\).

The relative velocity between the hob and the wheel in the fixed frame \(S_d\) is:

$$

\mathbf{v}_d^{(hg)} = (\boldsymbol{\omega}_d^{(hg)} \times \mathbf{r}_d^{(h)}) + E_{hg} \mathbf{j}

$$

where \(\boldsymbol{\omega}_d^{(hg)} = c_{gh} \mathbf{j} – \mathbf{L}_y(\phi’_h – \psi_h) \mathbf{k}\) and \(E_{hg}\) is the center distance for wheel generation. The equation of meshing for this process becomes:

$$

f = (\boldsymbol{\omega}_d^{(hg)} \times \mathbf{r}_d^{(h)}) \cdot \mathbf{n}_d^{(h)} + E_{hg} (\mathbf{j} \cdot \mathbf{n}_d^{(h)}) = 0

$$

This equation can be simplified to a trigonometric form:

$$

A \sin(\psi_h – \phi’_h) + B \cos(\psi_h – \phi’_h) + C = 0

$$

where \(A, B, C\) are functions of the hob surface point and normal. Using the half-angle tangent substitution \(x = \tan[(\psi_h – \phi’_h)/2]\), we obtain a quadratic equation which yields two solutions:

$$

\psi_{h1,2} = 2 \arctan\left( \frac{-A \mp \sqrt{A^2 + B^2 – C^2}}{C – B} \right) + \phi’_h, \quad \text{for } A^2+B^2-C^2 \ge 0

$$

These two solutions correspond to two distinct lines of contact between the hob and the wheel blank at each instant, leading to the formation of two sub-surfaces on the finished worm wheel. The final wheel tooth surface \(\Sigma_g\) is the union of the real (physical) parts of these two sub-surfaces:

$$

\mathbf{r}^{(g1)} = \mathbf{L}_z(-\psi_{g1}) [ \mathbf{L}_y(\psi_{h1}) \mathbf{r}^{(h)} – E_{hg} \mathbf{i} ], \quad \psi_{g1} = \psi_{h1}/c_{gh}

$$

$$

\mathbf{r}^{(g2)} = \mathbf{L}_z(-\psi_{g2}) [ \mathbf{L}_y(\psi_{h2}) \mathbf{r}^{(h)} – E_{hg} \mathbf{i} ], \quad \psi_{g2} = \psi_{h2}/c_{gh}

$$

This dual-line contact phenomenon is a hallmark of properly designed double-enveloping worm-gears and contributes to their high contact ratio.

5. Analysis of Geometric Characteristics

A complete modern design system must analyze the generated surfaces to predict performance. Key analyses include curvature, boundaries, sliding, and contact.

5.1 Relative Curvature and Contact Mechanics

The relative normal curvature between two contacting surfaces determines the size of the contact ellipse under load, which is critical for calculating contact stress. For line-contact surfaces, one relative principal curvature is zero (along the contact line), and the other, non-zero principal relative curvature \(\kappa_\sigma^{(12)}\) governs the contact width. A generalized formula derived from differential geometry is used:

$$

\kappa_\sigma^{(12)} = \frac{(\mathbf{b} – \boldsymbol{\omega}^{(12)} \times \mathbf{n})^2}{ [\mathbf{a}^{(12)} – 2(\boldsymbol{\omega}^{(12)} \times \mathbf{v}^{(12)})] \cdot \mathbf{n} – \mathbf{b} \cdot \mathbf{v}^{(12)} }

$$

Here, \(\mathbf{a}^{(12)}, \boldsymbol{\omega}^{(12)}, \mathbf{v}^{(12)}\) are the relative acceleration, angular velocity, and linear velocity of the two surfaces at the point of tangency. Vector \(\mathbf{b}\) is derived from the curvatures and torsions of the generating surface along its parameter lines. The direction of the contact line tangent \(\mathbf{e}_c\) is given by:

$$

\theta_c = \arctan\left( \frac{-(\mathbf{b} – \boldsymbol{\omega}^{(12)} \times \mathbf{n}) \cdot \mathbf{e}_u}{b_v \sin \gamma + \boldsymbol{\omega}^{(12)} \cdot \mathbf{e}_u} \right)

$$

where \(\mathbf{e}_u, \mathbf{e}_v\) are the parameter line tangents on the generating surface and \(\gamma\) is the angle between them.

5.2 Undercutting and Contact Boundary Lines

During generation, the envelope surface may develop singularities. The condition for undercutting (generation of a sharp edge or “root cut” on the generated surface) is given by the vanishing of a specific functional \(l_u\):

$$

l_u = \mathbf{b} \cdot \mathbf{v}^{(12)} – [\mathbf{a}^{(12)} – 2(\boldsymbol{\omega}^{(12)} \times \mathbf{v}^{(12)})] \cdot \mathbf{n} = 0

$$

Geometrically, this indicates points where the relative normal curvature becomes infinite. The line satisfying this condition on the tool is the limiting line for producing a regular worm or wheel surface.

Similarly, the boundary of the family of contact lines on the tool surface (the envelope of contact lines) is given by:

$$

l_c = [\mathbf{a}^{(12)} – (\boldsymbol{\omega}^{(12)} \times \mathbf{v}^{(12)})] \cdot \mathbf{n} = 0

$$

This line separates the active part of the tool that participates in generation from the inactive part.

5.3 Sliding Ratio and Engagement Angle

Sliding between mating surfaces affects wear and efficiency. The sliding ratios for the two surfaces at a contact point are:

$$

\xi^{(1)} = -\frac{ (\boldsymbol{\omega}^{(12)} \times \mathbf{n} – \mathbf{b}) \cdot \mathbf{v}^{(12)} }{ [\mathbf{a}^{(12)} – \boldsymbol{\omega}^{(12)} \times \mathbf{v}^{(12)}] \cdot \mathbf{n} }, \quad

\xi^{(2)} = \frac{ (\boldsymbol{\omega}^{(12)} \times \mathbf{n} – \mathbf{b}) \cdot \mathbf{v}^{(12)} }{ [\mathbf{a}^{(12)} – 2(\boldsymbol{\omega}^{(12)} \times \mathbf{v}^{(12)})] \cdot \mathbf{n} – \mathbf{b} \cdot \mathbf{v}^{(12)} }

$$

Note that \(\xi^{(1)} = 0\) when \(l_c=0\), meaning sliding vanishes in the direction normal to the contact line at the boundary line.

The engagement angle \(\theta_m\) is the angle between the contact line tangent \(\mathbf{e}_c\) and the relative velocity vector \(\mathbf{v}^{(12)}\). It is computed as \(\theta_m = |\theta_c – \theta_v|\), where \(\theta_v\) is the direction angle of \(\mathbf{v}^{(12)}\). An engagement angle near 90° promotes the formation of a hydrodynamic lubricant film.

5.4 Instantaneous Contact Lines and Contact Stripes

Under theoretical no-load conditions, the mating surfaces contact along instantaneous lines. When load is applied, elastic deformation causes these lines to broaden into contact stripes. Assuming a constant material deformation coefficient \(\Delta_m\) and equal pressure along a contact line, the half-width \(w_c\) of the contact stripe at a point is approximately:

$$

w_c = \sqrt{ 2 \Delta_m / \kappa_\sigma^{(12)} – \Delta_m^2 }

$$

The direction of this stripe is perpendicular to the contact line, along the direction of the non-zero relative principal curvature \(\kappa_\sigma^{(12)}\). Plotting these stripes for successive contact positions simulates the loaded tooth contact pattern (TCA – Tooth Contact Analysis), which is vital for assessing the quality of a worm-gear design.

6. Worm Thread Modification and Surface Measurement

6.1 End Relief Modification

To reduce entry and exit impact in double-enveloping worm-gears, local modification of the worm thread ends is often applied. A simple and effective method is to introduce a parabolic variation in the machining ratio during the generation of the end portions of the worm. If the modification starts at table angle \(\phi_{cs}\), the modified table angle for \(|\phi_c| \ge |\phi_{cs}|\) becomes:

$$

\phi_c = \phi_w \frac{N_w}{N_c} \pm a \left( \phi_w \frac{N_w}{N_c} – \phi_{cs} \right)^2

$$

where \(a\) is a modification coefficient and the sign is chosen based on the specific end and flank being cut.

6.2 CMM Measurement of the Worm

Verifying the accuracy of the manufactured worm helical surface is crucial. A Coordinate Measuring Machine (CMM) is used for this purpose. A grid of theoretical points on the worm surface must be calculated for the CMM to follow. The grid is defined in axial sections and radial lines. For a given axial section corresponding to a “unwound” rotation angle \(\phi_j\), and a radial distance \(r_k\) from the worm axis, the corresponding surface point coordinates \((x_w, y_w, z_w)\) are found by solving the system:

$$

\arctan(z_w / x_w) = \phi_j, \quad \sqrt{ E_{wg}^2 – (x_w^2 + z_w^2) + y_w^2 } = r_k

$$

subject to the worm surface equation \(\Sigma_h\). Here \(E_{wg}\) is the working center distance. The CMM probe is programmed to measure at these grid points, and the deviations from the theoretical coordinates represent the manufacturing errors of the worm thread (e.g., profile error, lead error). This process is essential for quality control of double-enveloping worm-gears.

7. Numerical Examples and Comparative Analysis

The unified computerized design method is illustrated through two numerical examples, both with a center distance of 100 mm, a gear ratio of 40:1, and a worm pitch diameter of 21 mm, but differing in the generation setup.

| Parameter | Example 1 (Orthogonal) | Example 2 (Non-Orthogonal) |

|---|---|---|

| Setup Type | \(\delta = 0\), \(\beta = \lambda\) | \(\beta = 0\), \(\delta = \lambda\) |

| Tool Plane Tilt \(\beta\) | Equal to lead angle \(\lambda\) | 0° |

| Worm Axis Offset \(\delta\) | 0° | Equal to lead angle \(\lambda\) |

7.1 Example 1: Orthogonal-Axis Double-Enveloping Worm-Gears

Analysis of the worm generation shows the contact lines on the tool plane are tangent to the boundary line (\(l_c=0\)), which lies within the tool face. This creates a region of double contact on the tool. The root-cut line (\(l_u=0\)) lies outside the generated worm thread, so no undercutting occurs.

For the wheel generation, the two sub-surfaces intersect along the root-cut line on the wheel tooth. The real parts of both sub-surfaces form the active tooth flank. The contact analysis reveals that every point on the worm thread contacts the wheel twice (dual-line contact) at different moments. The instantaneous contact pattern shows two distinct lines of contact. The worm thread is only partially in contact, with the non-contacting regions near the ends requiring significant relief modification. The calculated double-contact ratio for this type is 3.44.

7.2 Example 2: Non-Orthogonal-Axis Double-Enveloping Worm-Gears

In this case, the boundary line on the tool plane lies outside the physical tool, meaning there is no area of double contact during worm generation. The wheel generation produces two sub-surfaces that do not intersect within the active profile but meet at a microscopic step along the root-cut line (height ~0.005 mm), which is negligible compared to machining finish.

The contact analysis is more favorable. The worm thread is in nearly full contact. The contact pattern shows a central region of dual-line contact and end regions of single-line contact. Key performance metrics are summarized below:

| Metric | Value / Description |

|---|---|

| Dual-Line Contact Ratio | 3.11 (from 23° to -5° rotation) |

| Single-Line Contact Ratio | 1.78 (from -5° to -21° rotation) |

| Total Contact Ratio | 4.89 |

| Average Relative Curvature Radius | 112 mm |

| Average Engagement Angle | 76° (ranging from 55° to 90°) |

The contact stripes, calculated assuming a material deformation coefficient \(\Delta_m\), show their maximum width in the central region of the tooth and narrow near the boundaries and the root-cut line. The theoretical CMM measurement grid and the resulting profile/lead error chart can be generated, providing a complete blueprint for manufacturing verification.

8. Conclusion

The modern computerized approach to designing double-enveloping worm-gears provides a powerful and unified methodology. By synthesizing the two primary manufacturing models into one computational framework, designers can efficiently explore the design space. The integration of advanced geometrical analysis—encompassing curvature, boundary conditions, sliding, engagement angles, and loaded contact patterns—enables the optimization of these complex drives for high load capacity and efficiency. Furthermore, the direct link between the theoretical model and CMM measurement protocols ensures manufacturability and quality control.

However, to fully realize the potential of double-enveloping worm-gears and make them a more mainstream power transmission solution, further challenges must be addressed. These include the development of precise, long-lasting hobs; the establishment of more economical and reliable manufacturing, inspection, and assembly processes; and the validation of the predicted contact mechanics under heavy loads. The computational framework described herein forms the essential foundation for tackling these next steps in the advancement of double-enveloping worm-gear technology.