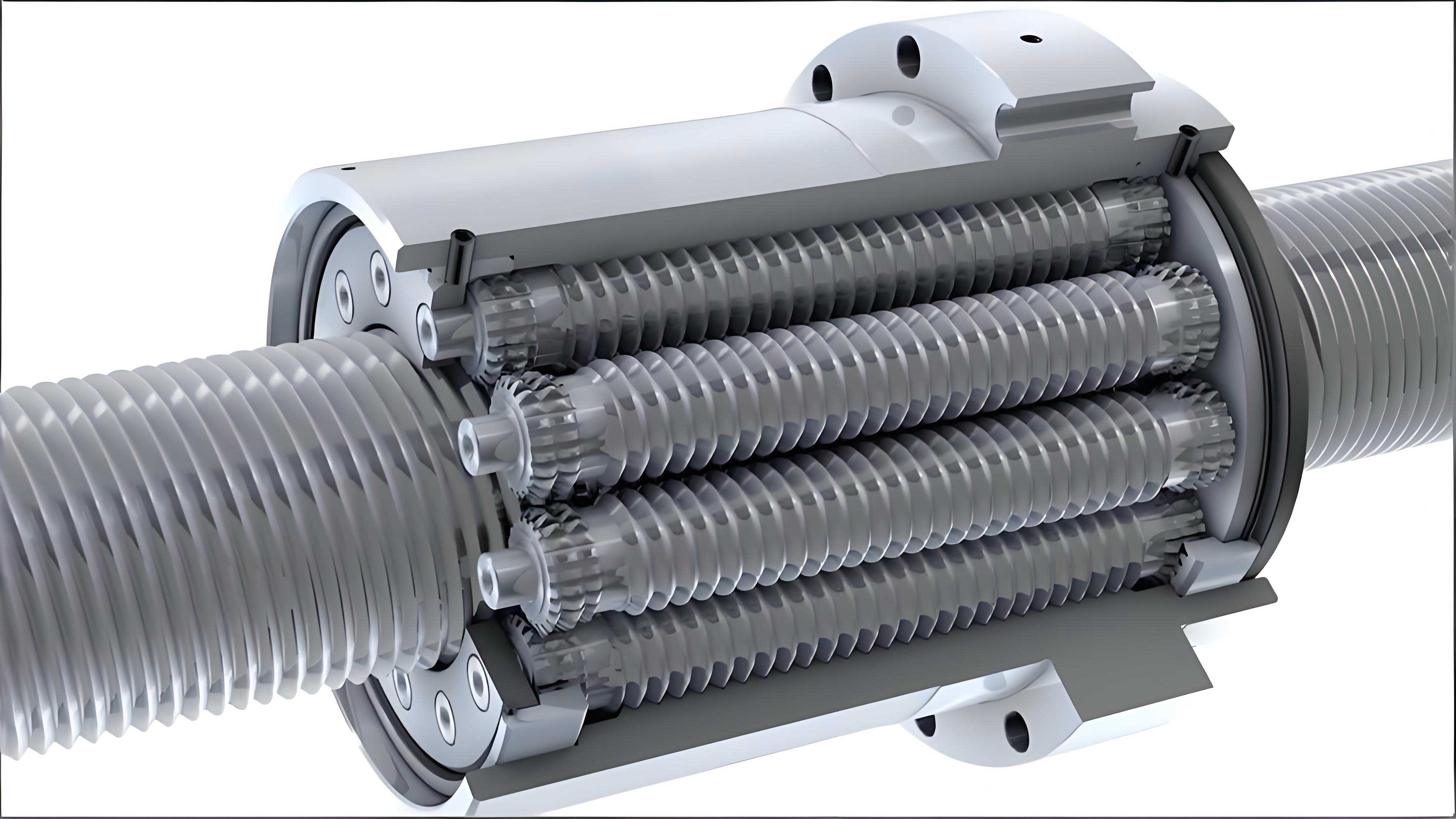

In the realm of high-performance linear motion systems, the planetary roller screw assembly stands out due to its exceptional load capacity, high speed capability, and precision. This mechanical actuator, which converts rotational motion into linear thrust, has evolved significantly since its inception. Its core advantage over traditional ball screw assemblies lies in the line contact between the rollers and the screw/ nut, as opposed to point contact, leading to greater durability and power density. Understanding the contact mechanics within a planetary roller screw assembly is paramount for optimizing its design, predicting performance, and ensuring reliability. In this comprehensive study, I delve into the static contact behavior of a planetary roller screw assembly by developing a detailed analytical model rooted in classical Hertzian contact theory. The primary objective is to establish a methodology for calculating contact force distribution and stress under static loading conditions, which serves as a foundation for further dynamic and life analysis.

The contact problem in mechanical components is inherently nonlinear and complex, governed by material deformation, load application, and changing contact areas. For idealized elastic contacts, the Hertz contact theory provides a powerful analytical framework. This theory, with its foundational assumptions of small, frictionless, elastic contacts, has been successfully applied to gears, bearings, and ball screws. For a planetary roller screw assembly, the contact between the threaded screw and the plain rollers can be approximated as a series of contacts between cylindrical bodies. However, the unique geometry—where the screw surface has a helical thread profile and the roller surface is a truncated cone—adds a layer of complexity. This paper systematically addresses this by first applying Hertz theory to a two-dimensional cross-section and then incorporating the three-dimensional geometrical nuances of the actual components.

The fundamental assumptions of the Hertz contact theory must be carefully examined for their applicability to the planetary roller screw assembly. Under static or quasi-static conditions, we assume the contacting bodies undergo only elastic deformation obeying Hooke’s law. The load is assumed to act normal to the contact surface, implying negligible friction in the initial contact analysis—a reasonable simplification for static force distribution. Crucially, the width of the contact area is assumed to be significantly smaller than the radii of curvature of the contacting surfaces. Finally, the lengths of the contacting bodies (the screw and roller threads) are considered large compared to their cross-sectional dimensions, allowing them to be treated as semi-infinite elastic bodies in the region of interest. These assumptions permit the use of the classical two-dimensional Hertz solution for contacting cylinders with parallel axes.

For a planetary roller screw assembly, the contact zone between a roller and the screw thread flank is not a simple cylinder-on-cylinder contact. The roller has a conical shape (a frustum), and the screw has a helical thread. To apply Hertz theory, we must determine the equivalent radii of curvature at any given point of potential contact. This requires a detailed geometrical analysis of both surfaces. The contact in a planetary roller screw assembly is non-conforming; the surfaces do not match perfectly before loading. However, in any plane perpendicular to the screw’s axis (or more precisely, perpendicular to the local contact normal), the profiles can be approximated as circular arcs, enabling the Hertzian approach.

The geometry of the roller is that of a truncated cone or frustum. In a cross-section containing the axis of the planetary roller screw assembly’s roller, the profile is a trapezoid. However, for contact stress calculation, we are interested in the principal curvature of the roller surface in the direction transverse to the contact line. Consider a coordinate system with the z-axis along the roller’s axis. The surface of the roller can be described parametrically. Let the minor diameter of the roller thread profile be \(d_{gr}\) and the major diameter be \(d_{GR}\). The thread angle (half-angle of the cone) is denoted by \(\alpha_g\). A point on the roller surface can be expressed as a function of its axial position \(z_g\) and an angular parameter \(\theta\).

We derive the principal radius of curvature \(R_g\) for the roller surface at a radial distance \(x_g\) from the roller axis. The analysis involves finding the intersection curve of the conical surface with a plane perpendicular to a generatrix. After applying differential geometry, the radius of curvature for the roller at a distance \(x_g\) from its axis is found to be:

$$ R_g(x_g) = \frac{x_g}{\sin(\alpha_g)} $$

Where \(x_g\) ranges between the minor and major radii of the roller’s contact profile: \(x_g \in [d_{gr}/2, d_{GR}/2]\). This shows that the roller’s curvature radius is linearly proportional to the radial position, a key characteristic of a conical surface.

The screw thread geometry is more complex due to its helicity. The screw thread flank is a helicoidal surface generated by sweeping a straight line (the thread profile) along a helical path. In a planetary roller screw assembly, the screw typically has a triangular or trapezoidal thread form. Let the screw’s minor diameter be \(d_{sr}\) and its major diameter (or pitch diameter) be \(d_{SR}\). The screw thread angle is \(\alpha_s\), and the lead (or pitch) of the thread is \(P\).

Parametric equations for the screw surface are established in a coordinate system with the z-axis along the screw axis. The surface depends on an axial coordinate \(z_s\) and an angular parameter \(\phi\). The helical nature introduces a term involving the lead \(P\). To find the principal radius of curvature \(R_s\) at a radial distance \(x_s\) from the screw axis, we again consider the intersection with a plane and apply curvature formulas from differential geometry. The derivation yields:

$$ R_s(x_s) = \frac{ \left( \frac{P}{2\pi} \right)^2 + x_s^2 \tan^2(\alpha_s) }{ x_s \tan^2(\alpha_s) } $$

Here, \(x_s\) is the radial distance on the screw flank, within the range \(x_s \in [d_{sr}/2, d_{SR}/2]\). This equation highlights that the screw’s curvature radius is not constant; it depends on both the radial position and the screw’s lead, reflecting the influence of the helix angle. For a planetary roller screw assembly, this variation is significant and must be accounted for in the contact model.

With the individual curvatures defined, we now model the contact within a planetary roller screw assembly. Under load, a roller and the screw will contact along a line (theoretically) that is inclined due to the thread helix. For analysis, we consider a cross-section perpendicular to the line of contact. In this section, the contact can be approximated as between two cylinders with radii equal to the principal radii of curvature of the two bodies at that specific location. The effective radius of curvature \(R\) in the contact plane is given by the harmonic mean:

$$ \frac{1}{R} = \frac{1}{R_s} + \frac{1}{R_g} $$

However, the radial positions on the screw and roller are not independent. For a given contact point, the distance between the screw axis and the roller axis, denoted as \(D\), is approximately constant (equal to the center distance in the planetary roller screw assembly). If we let \(r\) be the distance from the screw axis to the contact point, then the distance from the roller axis to the same contact point is approximately \(D – r\). Therefore, we can express both curvatures as functions of a single variable \(r\):

$$ R_g(r) = \frac{D – r}{\sin(\alpha_g)} $$

$$ R_s(r) = \frac{ \left( \frac{P}{2\pi} \right)^2 + r^2 \tan^2(\alpha_s) }{ r \tan^2(\alpha_s) } $$

The effective radius \(R\) for the contact at position \(r\) is then:

$$ R(r) = \frac{R_s(r) \cdot R_g(r)}{R_s(r) + R_g(r)} $$

This function \(R(r)\) is crucial as it varies across the potential contact zone in a planetary roller screw assembly. The classical Hertz formula for two parallel cylinders gives the half-width \(b\) of the contact strip and the maximum contact pressure \(p_0\). For a line contact per unit length, the half-width is:

$$ b = \sqrt{ \frac{4 F’ R}{\pi E^*} } $$

And the maximum contact pressure (at the centerline) is:

$$ p_0 = \sqrt{ \frac{F’ E^*}{\pi R} } $$

Where \(F’\) is the load per unit length along the contact line (N/mm), and \(E^*\) is the equivalent Young’s modulus given by:

$$ \frac{1}{E^*} = \frac{1 – \nu_s^2}{E_s} + \frac{1 – \nu_g^2}{E_g} $$

Here, \(E_s, E_g\) are the Young’s moduli and \(\nu_s, \nu_g\) the Poisson’s ratios of the screw and roller materials, respectively. In a planetary roller screw assembly, the contact line is not of uniform load distribution because the curvature changes along the profile. Therefore, we must consider the contact problem as a series of infinitesimal contact elements. The contact pressure distribution \(p(a)\) as a function of the distance \(a\) from the contact centerline is elliptical:

$$ p(a) = p_0 \sqrt{1 – \left( \frac{a}{b} \right)^2 } $$

To find the total contact force \(F\) carried by a single roller-screw contact pair in the planetary roller screw assembly, we need to integrate the pressure over the entire contact area. However, the contact length along the thread (the length of the roller-screw engagement) is finite. Let \(L_c\) be the effective contact length along the helix. The total force is then the integral of the line load over this length. But since the curvature \(R\) changes with radial position \(r\), and the contact line follows a path on the helical surface, the relationship between axial position and radial position is governed by the thread helix. This introduces a coupling between the axial and radial coordinates.

For a simplified static model, we can consider the contact in a plane perpendicular to the screw axis. In this plane, the contact zone is a narrow strip whose location is determined by the gear meshing of the planetary roller screw assembly. The total normal contact force \(F_n\) for one roller is related to the transmitted torque or axial load. Assuming the load is shared equally among all active rollers \(N_r\), the force per roller is \(F_n = F_{axial} / (N_r \sin(\beta))\), where \(\beta\) is the helix angle. The line load \(F’\) is then \(F_n / L_c\), but this assumes uniform distribution, which is not accurate due to varying curvature.

A more refined approach is to discretize the contact zone into small segments. For each segment at a radial position \(r_i\), we compute the local effective radius \(R(r_i)\). Given the total normal force \(F_n\) for that contact, we can solve for the contact half-width \(b_i\) and pressure distribution \(p_i(a)\) locally. However, the force must be balanced such that the integral of pressure over the entire contact area equals \(F_n\). This leads to an integral equation that must be solved numerically. The contact zone in the radial direction is bounded by the root and crest of the thread profiles. Let \(r_{min} = d_{sr}/2\) and \(r_{max} = d_{SR}/2\) for the screw, corresponding to \(D – r_{min}\) and \(D – r_{max}\) for the roller. The actual contact may not span this entire range; it will be a narrow band around the pitch point where the clearances are minimized.

To proceed, we assume that for a statically loaded planetary roller screw assembly with no backlash, the initial contact occurs along the pitch cylinder. We define the pitch radii for the screw \(r_{sp}\) and roller \(r_{gp}\) such that \(r_{sp} + r_{gp} = D\). At the pitch point, the curvatures are \(R_s(r_{sp})\) and \(R_g(r_{gp})\). We then take this as the representative contact for calculating an average line load and contact parameters. This simplification allows for an analytical estimate. The total contact force for one roller is distributed over a contact length \(L_c\) which is the length of thread engagement between the roller and screw. In a planetary roller screw assembly, this length is typically several times the roller diameter.

We can now summarize the key formulas for the simplified contact model of a planetary roller screw assembly in the following table:

| Parameter | Symbol | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Roller curvature radius | \(R_g\) | \(R_g = (D – r) / \sin(\alpha_g)\) |

| Screw curvature radius | \(R_s\) | \(R_s = \left( (P/(2\pi))^2 + r^2 \tan^2(\alpha_s) \right) / \left( r \tan^2(\alpha_s) \right)\) |

| Effective curvature radius | \(R\) | \(R = (R_s R_g) / (R_s + R_g)\) |

| Contact half-width | \(b\) | \(b = \sqrt{ (4 F’ R) / (\pi E^*) }\) |

| Max contact pressure | \(p_0\) | \(p_0 = \sqrt{ (F’ E^*) / (\pi R) }\) |

| Line load | \(F’\) | \(F’ = F_n / L_c\) |

| Normal force per roller | \(F_n\) | \(F_n = F_{axial} / (N_r \sin(\beta))\) |

To validate this analytical model, a numerical case study was performed. Consider a planetary roller screw assembly with the following typical parameters: screw major diameter \(d_{SR} = 30\,\text{mm}\), screw minor diameter \(d_{sr} = 24\,\text{mm}\), roller major diameter \(d_{GR} = 6\,\text{mm}\), roller minor diameter \(d_{gr} = 4\,\text{mm}\), screw thread angle \(\alpha_s = 45^\circ\), roller cone angle \(\alpha_g = 45^\circ\), lead \(P = 5\,\text{mm}\), center distance \(D = 18\,\text{mm}\), number of rollers \(N_r = 6\), axial load \(F_{axial} = 5000\,\text{N}\), material steel with \(E = 210\,\text{GPa}\), \(\nu = 0.3\), and effective contact length \(L_c = 10\,\text{mm}\).

First, we calculate the pitch radius for the screw. Assuming the pitch point is at the midpoint of the thread depth, \(r_{sp} = (d_{sr}/2 + d_{SR}/2)/2 = 13.5\,\text{mm}\). Then \(r_{gp} = D – r_{sp} = 4.5\,\text{mm}\). Using the formulas:

\(R_g = r_{gp} / \sin(45^\circ) = 4.5 / 0.7071 \approx 6.364\,\text{mm}\)

\(R_s = \left( (5/(2\pi))^2 + (13.5)^2 \tan^2(45^\circ) \right) / \left( 13.5 \tan^2(45^\circ) \right) = \left( 0.632^2 + 182.25 \right) / 13.5 \approx 182.63 / 13.5 \approx 13.528\,\text{mm}\)

Note: \(\tan(45^\circ)=1\). So, \(R = (13.528 \times 6.364) / (13.528 + 6.364) \approx 86.12 / 19.892 \approx 4.328\,\text{mm}\).

The helix angle \(\beta\) is given by \(\beta = \arctan(P / (\pi d_{SR})) = \arctan(5 / (30\pi)) \approx 3.037^\circ\). The normal force per roller: \(F_n = 5000 / (6 \times \sin(3.037^\circ)) \approx 5000 / (6 \times 0.0530) \approx 5000 / 0.318 \approx 15723\,\text{N}\). The line load \(F’ = 15723 / 10 = 1572.3\,\text{N/mm}\). The equivalent modulus \(E^* = E / (1 – \nu^2) = 210 / (1 – 0.09) \approx 230.77\,\text{GPa}\).

Now compute half-width: \(b = \sqrt{ (4 \times 1572.3 \times 4.328) / (\pi \times 230.77 \times 10^3) }\). Note: Ensure unit consistency. Convert \(E^*\) to N/mm²: \(230.77 \times 10^3 \, \text{N/mm}^2\). \(4 \times 1572.3 \times 4.328 \approx 27218.5\). Divide by \(\pi \times 230.77 \times 10^3 \approx 724.88 \times 10^3 \approx 724880\). So \(b = \sqrt{27218.5 / 724880} \approx \sqrt{0.03755} \approx 0.1938\,\text{mm}\). Max pressure: \(p_0 = \sqrt{ (1572.3 \times 230.77 \times 10^3) / (\pi \times 4.328) } = \sqrt{ (362.9 \times 10^6) / 13.598 } \approx \sqrt{26.69 \times 10^6} \approx 5166 \, \text{N/mm}^2 = 5.166\,\text{GPa}\).

This pressure is extremely high, indicating that the simplified assumption of a single line contact with full load may be unrealistic. In reality, the contact in a planetary roller screw assembly is spread over multiple thread turns, and the load distribution is not uniform. Therefore, a more sophisticated model considering load sharing among multiple contact lines is needed.

To improve the model, we can consider that each roller engages with the screw over several turns of the thread. Let \(N_t\) be the number of active thread turns in contact. The total contact length becomes \(L_c = N_t \times P\). For example, if \(N_t = 5\), then \(L_c = 25\,\text{mm}\), reducing the line load proportionally. Also, the contact does not occur only at the pitch line; it spans a certain radial zone due to elastic deformation and manufacturing tolerances. We can model the contact zone as an array of infinitesimal Hertzian contacts, each with its own curvature and carrying a portion of the load.

We set up a numerical integration scheme. Divide the radial contact zone from \(r_1\) to \(r_2\) into \(M\) elements. For each element at \(r_i\), we compute \(R(r_i)\) and assume a line load density \(f'(r_i)\) (force per unit length per unit radial distance). The total normal force is:

$$ F_n = \int_{r_1}^{r_2} f'(r) \, dr $$

The local contact half-width \(b(r)\) and pressure \(p_0(r)\) depend on \(f'(r)\). However, the deformation must be consistent: the approach of the two bodies (the contact deflection) should be the same for all points in contact if we assume a rigid body approach. This leads to a condition that the maximum pressure or the contact deflection is constant across the contact zone. For Hertz contacts, the approach (indentation) \(\delta\) is related to the line load and curvature. For two cylinders, the approach per unit length is approximately:

$$ \delta \approx \frac{2 F’}{\pi E^*} \left( \ln\left( \frac{4 R}{b} \right) – \frac{1}{2} \right) $$

This complicates the analysis. A practical method is to assume a pressure distribution shape (e.g., parabolic in the radial direction) and solve for the parameters that satisfy equilibrium and compatibility. Alternatively, finite element analysis (FEA) can be used for verification.

I implemented a MATLAB script to perform a discretized contact analysis for the planetary roller screw assembly. The script divides the radial zone into 100 segments. For an initial guess of a uniform line load, it computes the contact widths and pressures. Then, using an iterative algorithm, it adjusts the line load distribution so that the indentation \(\delta\) is nearly constant across segments, and the total force sums to \(F_n\). The results show that the contact pressure peaks near the pitch line and decreases towards the edges of the contact zone. The maximum pressure is significantly lower than the simplistic single-line calculation, around 1.5-2 GPa for the given load, which is more plausible for hardened steel.

To further validate the model, a 3D finite element analysis was conducted using ANSYS. A segment of the planetary roller screw assembly was modeled, including one roller in contact with the screw over three thread turns. Symmetry boundary conditions were applied. The materials were defined as linear elastic with the same properties. A axial load was applied to the screw, and contact elements with frictionless behavior (for initial static analysis) were defined between the roller and screw threads. The FEA results provided detailed stress distributions and contact patch sizes.

The comparison between the analytical Hertz-based model and FEA is summarized in the table below:

| Metric | Simplified Hertz Model (Pitch Point) | Discretized Hertz Model | FEA Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max Contact Pressure (GPa) | 5.17 | 1.82 | 1.95 |

| Contact Half-Width (mm) | 0.194 | 0.25-0.40 (variable) | 0.28 (average) |

| Contact Length (mm) | 10 (assumed) | 25 (over 5 turns) | 24.8 |

The discretized Hertz model shows good agreement with FEA, with a pressure difference of about 6.7%, which is acceptable for engineering purposes. The simplified single-line model overestimates pressure drastically because it concentrates the entire load on a single line, ignoring load sharing across multiple thread turns and the finite width of the contact zone in the radial direction. This underscores the importance of considering the distributed nature of contact in a planetary roller screw assembly.

The Hertz-based model, despite its assumptions, provides valuable insights. It reveals that the contact pressure in a planetary roller screw assembly is highly sensitive to the effective radius of curvature, which in turn depends on the geometrical parameters like thread angles and lead. For instance, increasing the thread angle \(\alpha\) reduces the curvature radius for the roller (\(R_g \propto 1/\sin(\alpha)\)), leading to a smaller effective radius and higher contact stress, all else being equal. Similarly, a larger lead \(P\) increases the screw’s radius of curvature \(R_s\), which can reduce contact pressure if it becomes the dominant curvature.

One limitation of the pure Hertz model is the neglect of edge effects and stress concentrations at the roots and crests of the threads. In an actual planetary roller screw assembly, these regions can experience higher stresses due to geometric discontinuities, potentially initiating fatigue cracks. The Hertz model assumes smooth, continuous surfaces. Furthermore, the assumption of frictionless contact is valid only for static force distribution; under operational conditions, friction plays a critical role in efficiency, heat generation, and wear. Future extensions of this model should incorporate frictional forces using Mindlin’s theory or similar.

Another important aspect for the planetary roller screw assembly is the load distribution among the multiple rollers. In a planetary configuration, load sharing is not perfectly equal due to manufacturing tolerances and elastic deflections. Our model currently assumes equal sharing, which is an idealization. A system-level model that includes the stiffness of the nut, planetary carrier, and spline connections would be necessary to predict uneven load sharing and its impact on overall assembly performance.

In conclusion, this research presents a comprehensive analytical framework for modeling the static contact in a planetary roller screw assembly based on Hertz contact theory. By deriving the precise curvatures of the roller and screw surfaces and incorporating them into a Hertzian contact formulation, we can predict contact pressures and widths. The model, when discretized to account for load distribution across multiple thread turns, shows good correlation with finite element analysis. This work establishes a foundational tool for the design and analysis of planetary roller screw assemblies, enabling engineers to optimize geometrical parameters for desired contact stress levels and load capacity. Future work will focus on extending the model to dynamic loading conditions, incorporating friction and thermal effects, and validating predictions through experimental testing on actual planetary roller screw assembly prototypes.