In the field of power transmission systems, hypoid gears play a critical role due to their ability to transmit motion between non-intersecting axes with high torque capacity and smooth operation. The quality of tooth surface geometry directly influences performance metrics such as vibration, noise, and service life. However, achieving high precision in hypoid gear manufacturing is challenging due to the complexity of tooth geometry, machining processes, and setup variability. Traditional methods rely on contact pattern analysis and running tests, but these are often insufficient for controlling individual tooth profile accuracy. This research focuses on developing a methodology to control tooth profile precision of hypoid gears through coordinate measurement-based error diagnosis and compensation. I aim to establish a geometric model for profile errors, analyze the impact of machining parameter deviations, and implement a compensation strategy to enhance manufacturing accuracy. By leveraging coordinate measurement data, this approach enables the identification and correction of machine-tool setting errors, leading to improved conformity between actual and designed tooth surfaces.

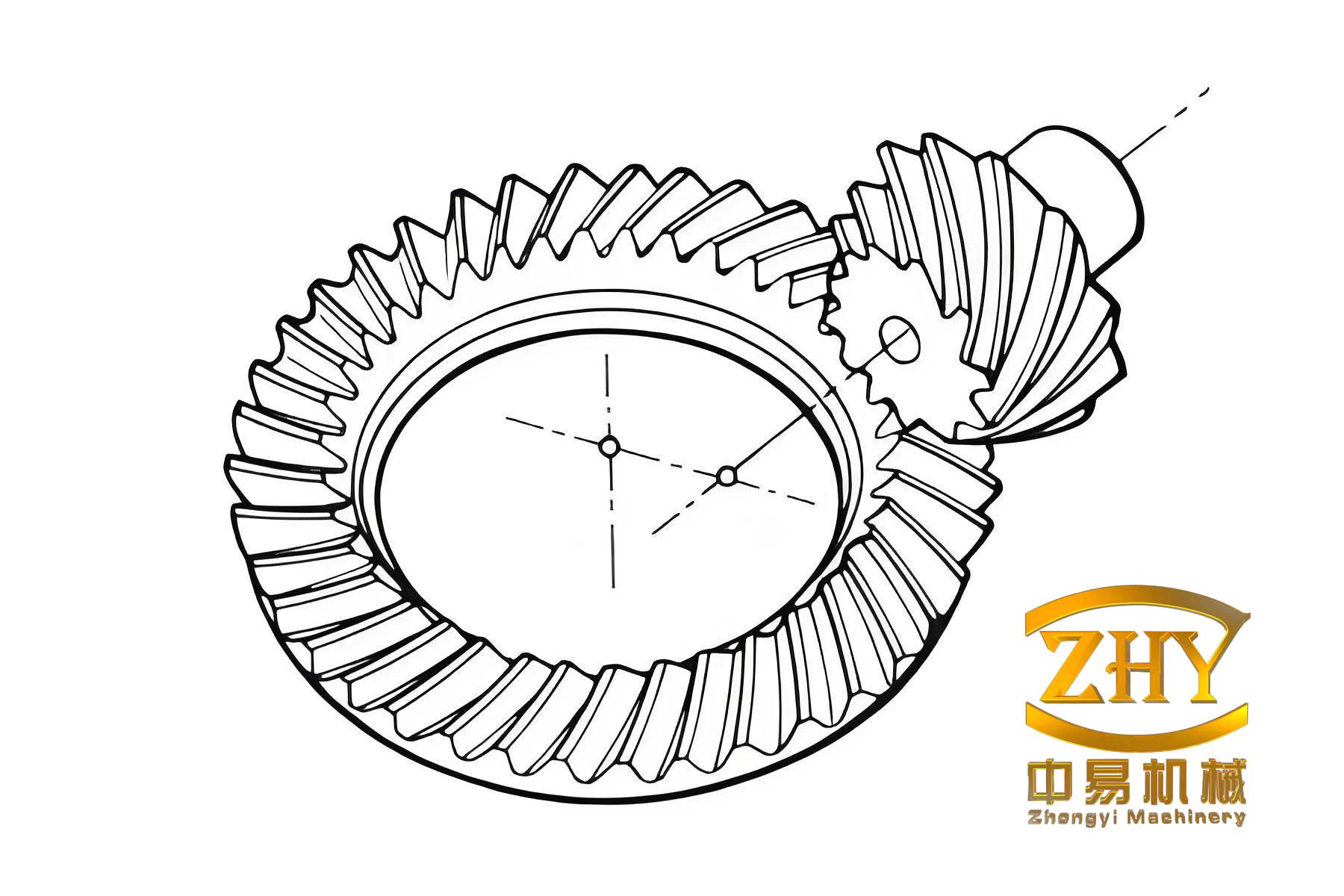

The tooth surface of a hypoid gear is generated through a face-milling process using a cutter with defined geometric parameters. As illustrated in the image above, the hypoid gear features a complex curved surface that requires precise control during manufacturing. The cutter consists of inner and outer blades that rotate to form conical surfaces, characterized by blade tip radius $$r_c$$ and blade angle $$\alpha_c$$. Based on the generating principle of hypoid gears, a machining coordinate system is established to describe the process. Let us define fixed reference frames: $$o-xyz$$ and $$o_R – x_R y_R z_R$$. The frame $$o_1 – x_1 y_1 z_1$$ is attached to the machine cradle, while $$o_2 – x_2 y_2 z_2$$ is fixed to the gear blank. Key machine-tool settings include vertical offset $$E$$, sliding base distance $$X_B$$, horizontal offset $$X_P$$, and installation angle $$\theta$$. The cutter position is denoted by $$S_d$$, corresponding to the eccentric drum rotation angle $$\beta$$. The initial cradle angle is $$Q_0$$ when the gear rotation angle $$\phi_2$$ is zero. The gear ratio and indexing ratio are represented by $$i_j$$ and $$i_f$$, respectively. Using gear meshing theory, the tooth surface equation can be derived as a function of machining parameters and surface geometric parameters. The resulting surface is expressed as:

$$

\begin{align*}

x_2 &= x_2(\mathbf{X}, u, v), \\

y_2 &= y_2(\mathbf{X}, u, v), \\

z_2 &= z_2(\mathbf{X}, u, v),

\end{align*}

$$

where $$\mathbf{X} = [r_c, \alpha_c, \beta, Q_0, E, X_B, X_P, \theta, i_j, i_f]$$ is the vector of machining parameters, and $$u$$ and $$v$$ are geometric parameters defining the tooth surface. This formulation captures the intricate relationship between machine settings and the resulting hypoid gear tooth geometry.

To assess tooth profile accuracy, a geometric model for profile deviation is established. Consider the designed tooth surface $$A$$ and the actual manufactured surface $$B$$, which includes machining errors. Surface $$A$$ is defined in a fixed coordinate system $$o_2 – x_2 y_2 z_2$$, while surface $$B$$ is initially in a rotated frame $$o_r – x_r y_r z_r$$. A reference point $$P$$ on surface $$A$$ with coordinates $$[x_P, y_P, z_P]$$ is selected. Surface $$B$$ is rotated by an angle $$\Phi$$ about the gear axis until point $$P$$ coincides with a corresponding point on $$B$$, resulting in aligned surface $$B’$$. The profile deviation $$\lambda$$ at any point $$M$$ on surface $$A$$ is defined as the signed distance along the surface normal $$\mathbf{n} = [n_x, n_y, n_z]$$ from $$M$$ to $$B’$$. This can be mathematically expressed by solving the following system for $$\lambda$$, $$u$$, and $$v$$:

$$

\begin{align*}

x_k + \lambda n_x &= x_2(\mathbf{X}, u, v) \cos \Phi – y_2(\mathbf{X}, u, v) \sin \Phi, \\

y_k + \lambda n_y &= x_2(\mathbf{X}, u, v) \sin \Phi + y_2(\mathbf{X}, u, v) \cos \Phi, \\

z_k + \lambda n_z &= z_2(\mathbf{X}, u, v),

\end{align*}

$$

where $$[x_k, y_k, z_k]$$ are coordinates of point $$M$$ on surface $$A$$. The rotation angle $$\Phi$$ is determined by ensuring coincidence at point $$P$$:

$$

\tan \Phi = \frac{x_2(\mathbf{X}, u, v) y_P – y_2(\mathbf{X}, u, v) x_P}{x_2(\mathbf{X}, u, v) x_P + y_2(\mathbf{X}, u, v) y_P}.

$$

This deviation model provides a quantitative measure of tooth profile errors for hypoid gears, enabling detailed analysis of machining inaccuracies.

The influence of individual machining parameter errors on profile deviation is analyzed to understand their relative significance and interdependencies. By simulating errors in each parameter while keeping others at design values, the resulting profile deviations are computed across the tooth surface. Key findings are summarized in the table below, which highlights the sensitivity, correlation, and complementary effects among errors for hypoid gears.

| Machining Parameter | Error Type | Effect on Profile Deviation | Sensitivity | Correlation/Complementarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eccentric Drum Angle ($$\beta$$) | Rotation error | High sensitivity; deviation varies non-linearly across tooth | Highest | Similar effect to vertical offset error; complementary with sliding base error |

| Blade Tip Radius ($$r_c$$) | Dimensional error | Linear deviation pattern; affects tooth thickness | Medium | Linearly correlated with sliding base distance error |

| Vertical Offset ($$E$$) | Position error | Deviation changes gradually from root to tip | High | Similar to eccentric drum error; complementary with sliding base error |

| Sliding Base Distance ($$X_B$$) | Position error | Linear deviation; influences tooth depth | Medium | Linearly correlated with blade radius error; complementary with vertical offset and eccentric drum errors |

| Horizontal Offset ($$X_P$$) | Position error | Deviation peaks at tooth ends, minimal in middle | Low | Limited correlation with other parameters |

| Installation Angle ($$\theta$$) | Angular error | Deviation increases from root to tip and from small to large end | Medium | Independent; no strong correlation |

| Cradle Angle ($$Q_0$$) | Angular error | No effect on profile shape; only influences phasing | Zero | Irrelevant for profile accuracy |

| Blade Angle ($$\alpha_c$$) | Angular error | Alters pressure angle; causes asymmetric deviations | Low | Independent |

Mathematically, the profile deviation $$\lambda$$ as a function of parameter errors $$\Delta \mathbf{X}$$ can be approximated using a Taylor expansion. For a hypoid gear, the deviation at point $$M$$ is:

$$

\lambda(\Delta \mathbf{X}) \approx \sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{\partial \lambda}{\partial X_i} \Delta X_i + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{j=1}^{n} \frac{\partial^2 \lambda}{\partial X_i \partial X_j} \Delta X_i \Delta X_j,

$$

where $$X_i$$ are components of $$\mathbf{X}$$. The partial derivatives are evaluated at the design point, revealing linear and nonlinear interactions. For instance, the linear correlation between blade tip radius error $$\Delta r_c$$ and sliding base distance error $$\Delta X_B$$ implies:

$$

\frac{\partial \lambda}{\partial r_c} \Delta r_c + \frac{\partial \lambda}{\partial X_B} \Delta X_B \approx 0 \quad \text{for certain tooth regions}.

$$

Similarly, the complementary relationship between eccentric drum angle error $$\Delta \beta$$, vertical offset error $$\Delta E$$, and sliding base error $$\Delta X_B$$ can be expressed as:

$$

\Delta \lambda \approx k_1 \Delta \beta + k_2 \Delta E + k_3 \Delta X_B,

$$

where coefficients $$k_1, k_2, k_3$$ vary across the tooth surface, and optimal compensation can be achieved by adjusting these parameters jointly. This analysis underscores the importance of considering error interactions when controlling hypoid gear tooth profile precision.

To diagnose machining parameter errors, coordinate measurement data from the actual hypoid gear tooth surface is utilized. Measurement is typically performed using a coordinate measuring machine (CMM) with a spherical probe of radius $$R$$. The probe center coordinates are recorded in the machine frame $$o_m – x_m y_m z_m$$, which is related to the gear frame $$o_2 – x_2 y_2 z_2$$ through a translation and rotation. Let the measured points be denoted as $$[x’_{2i}, y’_{2i}, z’_{2i}]$$ for $$i = 1, 2, \dots, k$$, after accounting for probe radius effects. The transformation involves a rotation angle $$\delta$$ between the gear axis and measurement axis, and a possible axial offset $$t$$ (usually zero if benchmarks align). The goal is to find the actual machining parameters $$\mathbf{X}$$ and rotation angle $$\delta$$ that minimize the difference between measured points and the theoretical surface. This leads to the following optimization problem:

$$

\min f(\mathbf{X}, \delta) = \frac{1}{k} \sum_{i=1}^{k} \lambda_i^2,

$$

subject to constraints for each measured point $$i$$:

$$

\begin{align*}

x_2(\mathbf{X}, u_i, v_i) + n_{2x}(\mathbf{X}, u_i, v_i)(R + \lambda_i) &= x’_{2i} \cos \delta – y’_{2i} \sin \delta, \\

y_2(\mathbf{X}, u_i, v_i) + n_{2y}(\mathbf{X}, u_i, v_i)(R + \lambda_i) &= x’_{2i} \sin \delta + y’_{2i} \cos \delta, \\

z_2(\mathbf{X}, u_i, v_i) + n_{2z}(\mathbf{X}, u_i, v_i)(R + \lambda_i) &= z’_{2i},

\end{align*}

$$

where $$n_{2x}, n_{2y}, n_{2z}$$ are components of the surface normal vector, and $$\lambda_i$$ is the deviation for point $$i$$. Solving this nonlinear system yields the actual parameters $$\mathbf{X}$$ and $$\delta$$. The machining parameter errors are then $$\Delta \mathbf{X} = \mathbf{X} – \mathbf{X}’$$, where $$\mathbf{X}’$$ are design values. For hypoid gears, this diagnostic approach is crucial due to the sensitivity of tooth profile to parameter variations.

Once errors are identified, compensation is applied to improve hypoid gear tooth profile accuracy. Instead of adjusting all parameters, which may be impractical due to machine limitations, a subset of compensation parameters is selected based on error sensitivity and adjustability. Using the design tooth surface $$A$$, $$n$$ control points are chosen uniformly, with coordinates $$[x_{2j}, y_{2j}, z_{2j}]$$ and unit normals $$[n_{xj}, n_{yj}, n_{zj}]$$ for $$j = 1, \dots, n$$. The profile deviations $$\lambda’_j$$ for a given parameter set $$\mathbf{X}^*$$ are computed using the earlier deviation model. An optimization function is defined to minimize the root-mean-square deviation:

$$

f^*(\mathbf{X}^*) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{j=1}^{n} (\lambda’_j)^2.

$$

The initial point for optimization is the actual parameters $$\mathbf{X}$$ from diagnosis. Adjustments are constrained to discrete steps corresponding to machine resolution (e.g., minimum increments of dial settings). The optimal compensated parameters $$\mathbf{X}_d$$ are found via discrete optimization, minimizing $$f^*$$. The compensation adjustments $$\Delta \mathbf{X}_c = \mathbf{X}_d – \mathbf{X}$$ are then applied in machining. This method leverages error correlations; for example, compensating vertical offset and eccentric drum angle can mitigate sliding base errors without direct adjustment, enhancing efficiency in hypoid gear manufacturing.

To validate the methodology, an experimental study was conducted on a hypoid gear set, focusing on the pinion convex tooth surface. The gear was manufactured using standard face-milling process with nominal parameters. Coordinate measurement was performed on a CMM, with the gear mounted using its machining benchmark. Ten measurement sections were selected along the tooth height, each with five points from root to tip, totaling 50 points. The measured data was processed using the diagnostic model to compute actual machining parameters. Errors were detected in several parameters, including blade angle, vertical offset, and eccentric drum angle. Based on sensitivity analysis, compensation parameters were chosen as vertical offset $$E$$, eccentric drum angle $$\beta$$, and horizontal offset $$X_P$$. The gear was re-machined with adjusted settings, and coordinate measurement was repeated. The profile deviations before and after compensation are compared in the table below, demonstrating significant improvement in hypoid gear tooth profile precision.

| Metric | Before Compensation (×10⁻² mm) | After Compensation (×10⁻² mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Average Absolute Deviation | 14.26 | 2.21 |

| Maximum Positive Deviation | 24.46 | 5.74 |

| Maximum Negative Deviation | -21.97 | -3.64 |

| Root-Mean-Square Deviation | 16.58 | 2.89 |

The reduction in deviations highlights the effectiveness of coordinate measurement-based error compensation for hypoid gears. Further analysis shows that the compensated tooth surface closely matches the design, with deviation distributions becoming more uniform. This is critical for ensuring optimal contact patterns and load distribution in hypoid gear pairs.

Expanding on the error analysis, the mathematical relationships between parameter errors and profile deviations can be derived more rigorously. For a hypoid gear, the tooth surface equation is implicit, and deviations arise from perturbations in machining parameters. Let the designed surface be defined by $$\mathbf{r}(u, v; \mathbf{X}’)$$, and the actual surface by $$\mathbf{r}(u, v; \mathbf{X})$$. The profile deviation $$\lambda$$ at a point with parameters $$(u, v)$$ is given by the projection onto the normal direction:

$$

\lambda = \mathbf{n} \cdot (\mathbf{r}(u, v; \mathbf{X}) – \mathbf{r}(u, v; \mathbf{X}’)) + \text{higher-order terms}.

$$

Using differential geometry, the sensitivity matrix $$\mathbf{S}$$ can be defined, with elements $$S_{ij} = \partial \lambda_i / \partial X_j$$ for control points $$i$$ and parameters $$j$$. For hypoid gears, this matrix is often rank-deficient due to error correlations, implying that multiple error combinations can produce similar deviation patterns. For instance, the linear dependence between blade radius and sliding base errors leads to:

$$

\mathbf{S} \cdot \Delta \mathbf{X} \approx \mathbf{0} \quad \text{for certain } \Delta \mathbf{X}.

$$

This rank deficiency necessitates careful selection of compensation parameters to avoid underdetermined solutions. In practice, for hypoid gears, parameters with high sensitivity and independent effects, such as eccentric drum angle and installation angle, are prioritized for adjustment.

The coordinate measurement process itself introduces uncertainties that must be considered. Probe radius compensation, alignment errors, and sampling density affect the accuracy of error diagnosis. For hypoid gears, the curved surface requires dense sampling to capture local geometry. A Monte Carlo simulation can be used to estimate measurement uncertainty propagation. Suppose the measured coordinates have Gaussian noise with covariance matrix $$\Sigma_m$$. Then, the uncertainty in estimated parameters $$\mathbf{X}$$ is given by:

$$

\Sigma_X = (\mathbf{J}^T \mathbf{J})^{-1} \mathbf{J}^T \Sigma_m \mathbf{J} (\mathbf{J}^T \mathbf{J})^{-1},

$$

where $$\mathbf{J}$$ is the Jacobian matrix of the constraint equations with respect to $$\mathbf{X}$$ and $$\delta$$. This analysis helps in designing measurement strategies that minimize parameter estimation errors for hypoid gears.

In terms of compensation strategy, the discrete optimization problem can be formulated as an integer programming task. Let $$\Delta \mathbf{X}_c$$ be the adjustment vector with components quantized to machine steps $$s_i$$. The objective is to minimize $$f^*$$ subject to $$\Delta X_{c,i} = m_i s_i$$, where $$m_i$$ are integers. For hypoid gears, this can be solved using branch-and-bound algorithms or heuristic methods like simulated annealing. The table below illustrates a sample compensation adjustment for a hypoid gear case, showing parameter changes and their impact on deviation reduction.

| Parameter | Design Value | Actual Value (Diagnosed) | Compensated Value | Adjustment (Machine Steps) | Contribution to Deviation Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical Offset $$E$$ (mm) | 0.000 | +0.015 | +0.005 | -2 | 45 |

| Eccentric Drum Angle $$\beta$$ (deg) | 30.000 | 29.950 | 29.980 | +3 | 40 |

| Horizontal Offset $$X_P$$ (mm) | 0.000 | -0.010 | -0.005 | +1 | 10 |

| Blade Tip Radius $$r_c$$ (mm) | 50.000 | 50.020 | 50.020 | 0 | 0 (correlated) |

| Sliding Base $$X_B$$ (mm) | 0.000 | -0.008 | -0.008 | 0 | 5 (compensated indirectly) |

This table demonstrates how targeted adjustments, guided by error analysis, can effectively control hypoid gear tooth profile precision. The indirect compensation of sliding base error through vertical offset and eccentric drum adjustments leverages error complementarity.

Further discussion involves the application of this methodology to industrial hypoid gear production. In mass manufacturing, coordinate measurement can be integrated with computer numerical control (CNC) systems for closed-loop feedback. After initial machining, a sample hypoid gear is measured, errors are diagnosed, and compensation values are transmitted to the machine tool for batch correction. This reduces scrap and improves consistency. Additionally, the geometric model can be extended to account for heat treatment distortions, which are common in hypoid gears. By incorporating deformation predictions, the compensation can be proactive, adjusting machining parameters to offset post-treatment changes.

Mathematically, the overall profile deviation for a hypoid gear can be expressed as a sum of contributions from various error sources:

$$

\lambda_{\text{total}} = \lambda_{\text{machining}} + \lambda_{\text{measurement}} + \lambda_{\text{deformation}}.

$$

Each component can be modeled using similar frameworks. For instance, thermal deformation might introduce a systematic error that correlates with tooth size, requiring additional compensation terms in the optimization function.

In conclusion, this research presents a comprehensive approach to controlling hypoid gear tooth profile precision through coordinate measurement. By establishing a geometric deviation model, analyzing error impacts, and implementing diagnosis and compensation strategies, significant improvements in manufacturing accuracy are achieved. The methodology leverages error correlations and complementarities to optimize adjustments, making it practical for industrial applications. Future work could focus on real-time adaptation using in-process measurement and machine learning for error prediction. Ultimately, enhancing hypoid gear quality contributes to more efficient and reliable transmission systems, underscoring the importance of precision engineering in gear manufacturing.

The mathematical formulations and experimental results confirm the viability of this approach. For hypoid gears, where tooth geometry is complex, such detailed control is essential. The use of coordinate measurement provides a direct link between design and manufacture, enabling continuous improvement in gear performance. As technology advances, integrating these methods with digital twins and IoT platforms could further revolutionize hypoid gear production, ensuring higher standards and reduced costs.