In my extensive experience with industrial machinery, I have found that the cycloidal drive stands out as a remarkably efficient and robust speed reduction mechanism. Its unique operational principles necessitate a dedicated approach to maintenance and fault management to ensure longevity and optimal performance. Through this article, I aim to share a comprehensive, first-hand perspective on the intricacies of cycloidal drive operation, systematic maintenance protocols, and effective fault diagnosis and resolution strategies. The cycloidal drive, often referred to in various contexts, is a cornerstone in many applications requiring high torque and precise motion control. We will delve deep into its mechanics, care routines, and problem-solving techniques, emphasizing the repeated importance of the ‘cycloidal drive’ in industrial settings.

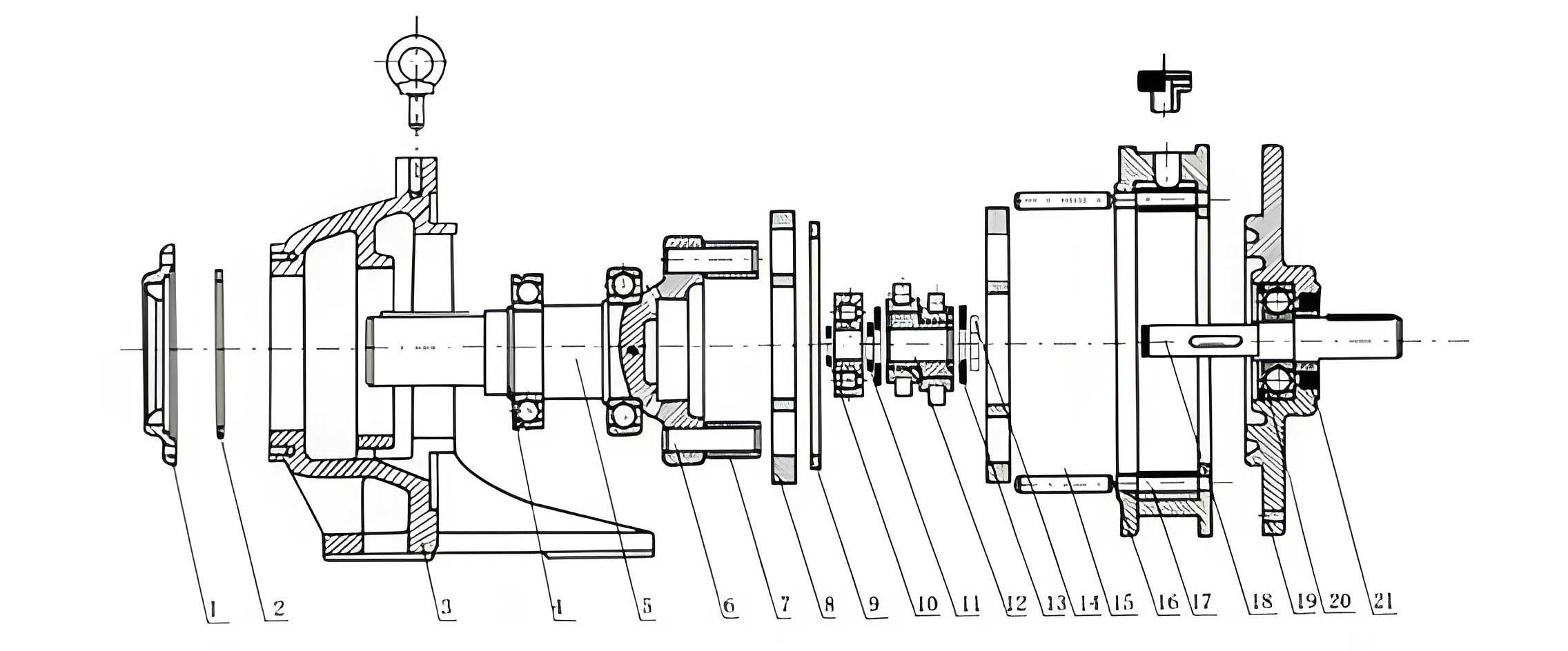

The foundational concept of the cycloidal drive revolves around a planetary gearing system that utilizes the engaging motion between a cycloidal disc and stationary pin gears. This design grants it exceptional torque density and smooth operation. To fully appreciate the maintenance needs, one must first understand its core working principle. A standard cycloidal drive consists of an input shaft, an eccentric cam or bearing, one or two cycloidal discs, a set of pin gears housed in a stationary ring, and an output mechanism. The input rotation is transferred to the cycloidal disc via the eccentric, causing the disc to undergo a composite motion: it both rotates on its own axis and wobbles or “nutates” within the pin ring. This action results in a significant speed reduction from input to output.

Mathematically, the profile of the cycloidal disc is generated by a point on a circle rolling inside or outside another circle. The epitrochoidal or hypotrochoidal curve is key. For a standard cycloidal drive where the disc rolls inside a ring of pins, the tooth profile can be derived from the following parametric equations, representing a hypotrochoid:

$$ x(\theta) = (R – r) \cos \theta + d \cos\left(\frac{R – r}{r} \theta\right) $$

$$ y(\theta) = (R – r) \sin \theta – d \sin\left(\frac{R – r}{r} \theta\right) $$

Here, \( R \) is the radius of the pin circle (generating circle), \( r \) is the radius of the rolling circle that generates the cycloidal curve, and \( d \) is the distance from the center of the rolling circle to the point tracing the curve. In a practical cycloidal drive, these parameters are meticulously calculated to ensure proper mating with the pins. The reduction ratio \( i \) of a single-stage cycloidal drive is primarily determined by the number of pins \( Z_p \) and the number of lobes on the cycloidal disc \( Z_d \). For the common one-tooth difference design, the relationship is:

$$ Z_p = Z_d + 1 $$

And the reduction ratio is given by:

$$ i = -\frac{Z_p}{Z_p – Z_d} = -Z_p $$

The negative sign indicates a reversal in the direction of rotation. This high ratio in a compact space is a hallmark of the cycloidal drive. The force transmission through multiple pin contacts distributes load, enhancing durability—a feature we must preserve through maintenance. The following table summarizes key geometric and kinematic parameters for a standard cycloidal drive design:

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Value/Relationship | Significance for Maintenance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Pin Gear Teeth | \( Z_p \) | e.g., 40, 41, 42 | Determines reduction ratio; wear alters effective count. |

| Number of Cycloidal Disc Lobes | \( Z_d \) | \( Z_p – 1 \) | Directly engages pins; primary wear surface. |

| Eccentricity Offset | \( e \) | Typically 1-5 mm | Critical for wobble motion; misalignment causes premature failure. |

| Pin Circle Diameter | \( D_p \) | Calculated from \( Z_p \) and pin diameter | Housing integrity is vital for pin alignment. |

| Reduction Ratio | \( i \) | \( i = Z_p \) (for single stage) | Performance baseline; changes indicate internal slippage or damage. |

Transitioning from theory to practice, the daily and periodic upkeep of a cycloidal drive is non-negotiable for sustained operation. I cannot overstate the correlation between disciplined maintenance and the extended service life of a cycloidal drive. The protocol begins with lubrication, the lifeblood of any gear system. For a new cycloidal drive, the initial run-in period is critical. After the first 100 hours of operation, the factory-fill oil must be completely drained and replaced. This removes any initial wear particles and contamination. Subsequent oil change intervals depend heavily on operational duty cycles and environmental conditions. I recommend adhering to a schedule similar to the one below, but always consult the specific manufacturer’s guidelines for your cycloidal drive model.

| Operational Condition | Recommended Oil Change Interval | Inspection Tasks During Change |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Duty (≤8 hours/day, clean environment) | Every 6 months or 2500 hours | Check for metal debris, assess oil viscosity and clarity. |

| Heavy Duty (>8 hours/day, high load) | Every 3-4 months or 1500 hours | Thorough inspection of oil for contamination and particle analysis. |

| Severe Duty (Dusty, moist, or high-temperature environment) | Every 2-3 months or 1000 hours | Clean housing interior meticulously; check seals; consider synthetic oils. |

| Continuous Operation (24/7) | Quarterly (3 months) regardless of hours | Implement continuous oil monitoring systems if possible. |

When performing an oil change, the procedure must be meticulous. First, run the cycloidal drive until it reaches operating temperature to suspend contaminants. Then, drain the oil completely. I always flush the interior with a light flushing oil or the new lubricant to displace old residue. Inspect the drained oil for glitter-like particles (initial wear) or larger chunks (indicative of active failure). The oil level must be checked regularly—weekly under normal conditions, daily in severe service. Use only the grade and type of oil specified for the cycloidal drive. The oil volume \( V \) required can often be estimated from the housing size. A simple formula for a cylindrical housing is:

$$ V \approx \pi \left(\frac{D}{2}\right)^2 L \cdot \phi $$

where \( D \) is the internal housing diameter, \( L \) is the length, and \( \phi \) is a fill factor (typically 0.7-0.8). Underfilling leads to inadequate lubrication, while overfilling can cause churning and overheating.

Alignment is another pillar of cycloidal drive health. Misalignment between the drive and the driven unit induces non-torsional forces that severely stress bearings and gears. We must periodically check the concentricity of couplings using dial indicators or laser alignment tools. The allowable misalignment for a cycloidal drive is often stricter than for other reducers due to its precise internal clearances. A general rule I follow is to keep angular misalignment below 0.05 degrees and parallel offset below 0.1 mm. Record alignment values over time to track degradation.

Mechanical fastening is deceptively simple yet crucial. All foundation bolts, flange bolts, and mounting hardware should be torqued to the manufacturer’s specification. I implement a quarterly check on all external fasteners using a calibrated torque wrench. Loose bolts allow vibration, which leads to fretting, increased noise, and ultimately, catastrophic failure. If a cycloidal drive exhibits unusual vibration, the first step is always to verify the integrity of every bolt connection, especially the main housing to the baseplate.

Temperature and noise monitoring serve as the first line of defense against impending faults. A cycloidal drive running smoothly will have a stable temperature slightly above ambient, typically 40-60°C. An abrupt rise beyond 70°C signals trouble. The heat generation \( Q \) can be loosely correlated with power loss \( P_{loss} \):

$$ Q \approx P_{loss} = P_{in} (1 – \eta) $$

where \( P_{in} \) is input power and \( \eta \) is the drive efficiency. A sudden increase in \( Q \) for constant \( P_{in} \) points to increased friction from wear, lubrication failure, or binding. Similarly, auditory inspection is vital. A healthy cycloidal drive produces a characteristic hum. Changes like grinding, knocking, or irregular clicking necessitate immediate investigation. I recommend using a stethoscope or vibration analyzer to pinpoint the source.

Seal integrity is paramount for preventing lubricant leakage and contaminant ingress. The lip seals or mechanical seals around the input and output shafts should be inspected monthly for signs of weeping, cracking, or hardening. Replacing seals during scheduled downtime is far cheaper than repairing a contaminated cycloidal drive. When installing new seals, ensure the shaft surface is smooth and free of scratches to prevent early seal wear.

Despite rigorous maintenance, faults can occur. My approach to fault analysis in a cycloidal drive is systematic: observe symptoms, identify the root cause, and execute a precise repair. The most common issues stem from lubrication, overload, and fatigue. Below is an extensive table detailing frequent faults, their root causes, diagnostic methods, and corrective actions. This compilation is drawn from years of hands-on troubleshooting with various cycloidal drive units.

| Observed Fault/Symptom | Potential Root Causes | Diagnostic Checks | Recommended Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overheating (>70°C) | Insufficient or degraded lubricant; incorrect lubricant viscosity; bearing preload failure; misalignment; overload; cooling fins clogged. | Check oil level and condition; measure input current/power; perform alignment check; inspect bearings for roughness. | Replace with correct grade/quantity of oil; realign drive train; reduce load if possible; clean housing exterior; replace faulty bearings. |

| Excessive Vibration & Noise | Loose mounting bolts; worn eccentric bearing (input); damaged cycloidal disc lobes; severe pin or bushing wear; imbalance; coupling wear. | Torque check all bolts; stethoscope to locate noise source; inspect internal components after disassembly; check coupling condition. | Tighten all fasteners to spec; replace eccentric bearing and/or cycloidal disc; replace worn pins/bushings; balance rotating assembly. |

| Loss of Output Torque or Slipping | Sheared key on input eccentric or output shaft; severely worn cycloidal disc or pins; broken internal components (e.g., pins). | Check for free rotation of input vs output; disassemble and inspect keyways, disc lobes, and pins for deformation or breakage. | Replace sheared key and inspect keyways for damage; replace worn cycloidal disc and/or pin set; repair or replace damaged housing. |

| Oil Leakage | Failed shaft seals; damaged seal mating surfaces; overfilled housing; breather vent clogged; cracked housing. | Visual inspection for leak paths; check breather; measure oil level; examine seal lips and shaft surfaces. | Replace seals; polish or sleeve damaged shafts; correct oil level; clear breather; repair or replace housing if cracked. |

| Increased Backlash or Play | Worn needle bearings on pins; worn output mechanism (e.g., wobble plate pins); worn cycloidal disc bore; eccentric bearing clearance increase. | Manual rotation to feel play; disassemble and measure wear on pins, disc bore, and bearings; check eccentric bearing axial/radial play. | Replace worn needle bearings/bushings; replace output mechanism components; replace cycloidal disc; adjust or replace eccentric bearing. |

| Failure to Start or Sudden Seizure | Complete lubricant failure; foreign object ingestion; catastrophic bearing failure; massive internal jamming due to part breakage. | Attempt manual rotation; inspect oil sump; disassemble completely to assess damage level. | Full overhaul. Replace all damaged components (bearings, disc, pins, seals). Flush housing thoroughly. Investigate root cause (e.g., contaminant source). |

Specific component failures warrant detailed repair techniques. For instance, replacing the eccentric bearing is a delicate task. The bearing is often a press-fit on the eccentric portion of the input shaft. I use two pry bars placed symmetrically on the bearing’s inner race, applying balanced force to avoid cocking. The formula for the extraction force \( F_{ext} \) can be estimated from the interference fit pressure \( p \), friction coefficient \( \mu \), and contact area \( A \):

$$ F_{ext} \approx \mu \cdot p \cdot A $$

Using unbalanced force or hammering risks bending the shaft or cracking the adjacent cycloidal disc—a costly mistake. Similarly, when keyways on the eccentric sleeve or output shaft wear out, the repair depends on damage extent. If the original keyway is wallowed out, one can machine a new keyway at a position 180 degrees opposite, provided there is sufficient material. The new keyway must be precisely aligned to maintain balance. The shear strength \( \tau_{key} \) of the new key must be verified:

$$ \tau_{key} = \frac{2T}{w \cdot l \cdot d} \leq \tau_{allowable} $$

where \( T \) is transmitted torque, \( w \) is key width, \( l \) is key length, and \( d \) is shaft diameter. If the calculated stress is too high, replacing the entire sleeve or shaft with a genuine part from the original cycloidal drive manufacturer is safer.

Lubrication-related failures are pervasive. Using an oil with improper additives or viscosity can lead to accelerated wear of the cycloidal disc and pins. The film thickness \( h \) in the elastohydrodynamic (EHD) contact between the cycloidal disc lobe and the pin can be approximated by the Dowson-Higginson equation:

$$ h_{min} \propto (\eta_0 u)^{0.67} \alpha^{0.53} R^{0.464} E’^{-0.073} W^{-0.067} $$

where \( \eta_0 \) is dynamic viscosity, \( u \) is rolling speed, \( \alpha \) is pressure-viscosity coefficient, \( R \) is reduced radius, \( E’ \) is effective elastic modulus, and \( W \) is load per unit width. This shows how critical correct viscosity (\( \eta_0 \)) is to maintain a protective film. A drop in film thickness leads to boundary lubrication and rapid wear. Therefore, I always insist on using the exact oil grade recommended for the specific operating temperature range of the cycloidal drive.

Overload failure is another critical mode. When a cycloidal drive is subjected to torque beyond its rated capacity, the pins and cycloidal disc lobes experience plastic deformation or fracture. The maximum shear stress \( \tau_{max} \) on a pin under load \( F \) is:

$$ \tau_{max} = \frac{16F}{\pi d_p^3} $$

for a solid pin of diameter \( d_p \). Exceeding the material’s yield strength causes permanent damage. To prevent this, ensure the drive is not undersized for the application. Installing torque limiters or overload clutches in the drive train can protect a valuable cycloidal drive from such abuse.

Fatigue failures occur over time due to cyclic loading. The cycloidal disc, with its complex lobe profile, is susceptible to bending fatigue at the lobe roots. The stress concentration factor \( K_t \) at the root must be considered in design. For maintenance, regular oil analysis to detect increasing iron particles can provide early warning of fatigue spalling on these surfaces. Vibration analysis can also detect the characteristic frequency modulation caused by a damaged lobe engaging the pins. The fault frequency \( f_{fault} \) related to a damaged cycloidal disc lobe is:

$$ f_{fault} = f_{r} \times Z_d $$

where \( f_{r} \) is the rotational frequency of the cycloidal disc relative to the housing. Monitoring vibration spectra for peaks at this frequency and its harmonics is a proactive maintenance strategy for any critical cycloidal drive.

In my practice, I advocate for the establishment of a dedicated health monitoring system for every major cycloidal drive installation. This system should log operational parameters such as temperature, vibration amplitude at key frequencies, and oil condition (via periodic sampling). Trending this data allows for predictive maintenance, where repairs are scheduled just before a potential failure, minimizing unplanned downtime. The table below outlines a suggested monitoring schedule and parameters for a high-availability cycloidal drive system.

| Monitoring Parameter | Method/Tool | Frequency | Alarm Threshold (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bearing Housing Temperature | RTD or Infrared Thermometer | Continuous or Daily Log | 70°C (158°F) |

| Vibration Velocity (RMS) | Accelerometer on Housing | Weekly | 4.5 mm/s (for this size drive) |

| Oil Analysis (Metals, Viscosity, Water) | Laboratory Oil Sample | Every Oil Change or Quarterly | Fe > 100 ppm, Si > 25 ppm, Viscosity change > ±10% |

| Noise Level (dB) | Acoustic Meter | Monthly | Increase of 5 dB above baseline |

| Output Speed Consistency | Tachometer | Monthly | Fluctuation > ±2% of set speed |

Finally, the philosophy of continuous improvement should be applied to cycloidal drive management. Every maintenance intervention and fault repair is a learning opportunity. Documenting findings, solutions, and the subsequent performance creates a valuable knowledge base. This enables the refinement of maintenance intervals, the optimization of spare parts inventory, and the development of better installation procedures for future cycloidal drive units. For example, if a particular model of cycloidal drive consistently shows eccentric bearing failure at 10,000 hours, one can proactively schedule bearing replacement at 9,000 hours, thus avoiding in-service failure.

In conclusion, the reliable operation of a cycloidal drive is a direct function of understanding its unique kinematics, implementing a rigorous and adaptive maintenance regimen, and possessing a systematic methodology for fault diagnosis and repair. The cycloidal drive, with its elegant mechanical principle, demands respect and careful attention. By integrating the theoretical insights with practical steps outlined here—from the mathematics of the cycloidal curve to the hands-on techniques for bearing replacement—we can ensure that these drives deliver their full potential in terms of efficiency, longevity, and productivity. Let this guide serve as a foundational reference for engineers and maintenance professionals dedicated to mastering the care of the indispensable cycloidal drive.