In the realm of automotive engineering, the pursuit of efficiency, reliability, and driver comfort has led to the widespread adoption of Electric Power Steering (EPS) systems. As an engineer focused on steering technologies, I have dedicated significant effort to designing and optimizing EPS systems for various vehicle platforms. This article delves into the comprehensive design and calculation process for an EPS system, with a particular emphasis on the screw gear transmission—a critical component that enables torque amplification and motion conversion. The screw gear, often referred to as a worm gear in specific contexts, plays a pivotal role in ensuring smooth and responsive steering assistance. Through this work, I aim to share insights into parameter matching, screw gear design, nonlinear contact analysis, and experimental validation, all from a first-person perspective of hands-on development and analysis.

The evolution of steering systems from hydraulic to electric power steering marks a significant leap in automotive technology. EPS systems offer notable advantages, including reduced energy consumption, elimination of hydraulic fluid leaks, and enhanced controllability through electronic integration. My involvement in EPS projects has underscored the importance of tailoring the system to specific vehicle requirements, especially in terms of torque output and packaging constraints. In this article, I will guide you through the entire process, from theoretical derivations to practical implementations, ensuring that the screw gear transmission is meticulously designed to meet stringent performance criteria. The screw gear mechanism, with its unique ability to provide high reduction ratios in compact spaces, is central to achieving the desired助力转矩 for vehicles requiring substantial steering assistance.

Introduction to EPS System Composition and Working Principle

As I embark on designing an EPS system, it is essential to understand its fundamental components and operational logic. The EPS system typically comprises a torque sensor, an electric助力 motor, a screw gear reduction mechanism, an electronic control unit (ECU), and optionally an electromagnetic clutch. In my design approach, I prioritize simplicity and cost-effectiveness, often omitting the clutch when feasible, as it reduces complexity and potential failure points. The torque sensor, which I typically select as a contact-type potentiometer for its reliability, detects the driver’s steering input and converts it into a voltage signal. This signal, along with vehicle speed and engine转速 inputs, is processed by the ECU to determine the required assist torque based on a pre-programmed助力 curve.

The working principle revolves around real-time feedback and control. When the driver turns the steering wheel, the torque sensor measures the applied torque and sends it to the ECU. Simultaneously, the ECU receives pulse signals indicating vehicle speed and engine speed. Using these inputs, the ECU calculates the optimal assist current to drive the electric motor. The motor then generates torque, which is transmitted through the screw gear reduction mechanism to the steering rack or pinion, thereby reducing the effort required by the driver. This process ensures that assistance is proportional to driving conditions—higher at low speeds for maneuverability and lower at high speeds for stability. The screw gear transmission is instrumental here, as it not only amplifies the motor torque but also changes the direction of motion, making it ideal for packaging in tight engine compartments.

To illustrate the system’s architecture, I have summarized the key interactions in Table 1, which outlines the components and their functions. This table serves as a reference throughout the design process, ensuring all elements are cohesively integrated.

| Component | Function | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Torque Sensor | Measures steering input torque and converts to voltage signal | Typically 5V output; contact-type potentiometer used |

| Electric Motor | Generates assist torque based on ECU command | 170W brushed motor selected for cost and performance |

| Screw Gear Mechanism | Reduces motor speed and amplifies torque; changes motion direction | Central to achieving high reduction ratio; designed as worm gear set |

| Electronic Control Unit (ECU) | Processes inputs and computes assist current; implements助力 curve | Max output current 35A; includes fail-safe features |

| Vehicle Speed Sensor | Provides speed pulse signal (e.g., 50Hz per revolution) | Critical for speed-sensitive assistance |

| Engine Speed Sensor | Provides engine转速 pulse signal (e.g., 5Hz per revolution) | Used for system activation and diagnostics |

The screw gear transmission, in particular, demands careful attention due to its nonlinear contact behavior and efficiency considerations. In the following sections, I will detail the parameter matching process, screw gear design, and analytical validation, all while emphasizing the role of the screw gear in meeting system objectives.

Parameter Matching for EPS System

To ensure the EPS system meets the specific needs of a target vehicle, I begin with a thorough parameter matching exercise. For this case, I consider a vehicle with the following baseline data: curb weight of 1,420 kg, front axle mass of 950 kg, maximum speed of 180 km/h, vehicle speed signal of 5V pulse (50 Hz per revolution), and engine speed signal of 5V pulse (5 Hz per revolution). The primary goal is to determine the required assist torque and subsequently size the motor and screw gear reduction ratio accordingly.

Using a torque-angle tester, I measured the maximum ground resistance torque under full load conditions, which was found to be 28 N·m. For a comfortable driving experience, drivers typically require a steering feel of 5–6 N·m; thus, the EPS system must provide an assist torque of approximately 23 N·m to overcome the resistance. This requirement drives the selection of the electric motor and the screw gear reduction ratio. I opted for a cost-effective 170W brushed motor with a rated current of 30A and a rated torque of 1.6 N·m. The screw gear mechanism must amplify this motor torque to achieve the desired assist output.

The overall efficiency of the EPS system, considering mechanical losses in the screw gear and other components, is estimated at 80%. Therefore, the required reduction ratio \( i \) can be calculated using the formula:

$$ i = \frac{T_{\text{assist}}}{T_{\text{motor}} \times \eta} $$

where \( T_{\text{assist}} = 23 \, \text{N·m} \), \( T_{\text{motor}} = 1.6 \, \text{N·m} \), and \( \eta = 0.8 \). Substituting the values:

$$ i = \frac{23}{1.6 \times 0.8} = \frac{23}{1.28} \approx 18.5 $$

Thus, a reduction ratio of 18.5:1 is necessary. With this ratio, the actual assist torque output becomes:

$$ T_{\text{output}} = 1.6 \times 18.5 \times 0.8 = 23.7 \, \text{N·m} $$

which satisfies the vehicle’s requirement. The screw gear transmission is designed to provide this reduction ratio while ensuring smooth operation and minimal backlash.

Given the packaging constraints in the vehicle’s front compartment, I chose a pinion-type EPS (P-EPS) configuration, where the screw gear mechanism is compact and integrates seamlessly with the steering column. The system must also meet an IP67防护等级 for dust and water resistance. Table 2 summarizes the matched parameters for the EPS system, which guide the subsequent screw gear design.

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Motor Type | Brushed DC Motor | 170W power rating, 30A rated current |

| Motor Rated Torque | 1.6 N·m | At rated operating conditions |

| Torque Sensor Type | Contact Potentiometer | 5V supply; linear output |

| ECU Max Current | 35 A | Peak capability for overload scenarios |

| Screw Gear Reduction Ratio | 18.5:1 | Critical for torque amplification |

| System Efficiency | 80% | Includes mechanical losses in screw gear |

| Protection Level | IP67 | For durability in harsh environments |

This parameter matching forms the foundation for designing the screw gear transmission. The screw gear must not only achieve the 18.5:1 ratio but also operate efficiently without self-locking to allow manual steering in case of power failure. In the next section, I will delve into the detailed design of the screw gear mechanism, highlighting geometric calculations and material selections.

Design of the Screw Gear Reduction Mechanism

With the reduction ratio established, I focus on designing the screw gear transmission. The screw gear, comprising a worm (screw) and a worm wheel, is a specialized gear set that offers high reduction ratios in a single stage. For this EPS application, I designed a screw gear with a 2-start worm to achieve a large lead angle, preventing self-locking and enabling reverse driving capability—where the worm wheel can drive the worm if needed. This is crucial for maintaining steering feel and safety.

The basic parameters of the screw gear are derived from standard worm gear design principles, tailored for automotive EPS requirements. I selected a module of 2.15 mm and a center distance of 46.5 mm to fit within spatial constraints. The worm has a lead angle of 19°17′ and a right-hand helix direction, while the worm wheel has 37 teeth to achieve the desired ratio. The lead angle is calculated to ensure efficiency and avoid self-locking; for a screw gear, the condition for non-self-locking is that the lead angle exceeds the friction angle. Using the coefficient of friction \( \mu = 0.07 \) for the material pair, the friction angle \( \phi \) is:

$$ \phi = \arctan(\mu) = \arctan(0.07) \approx 4^\circ $$

Since the lead angle of 19°17′ is greater than \( \phi \), the screw gear will not self-lock, allowing reverse motion. This design choice enhances system responsiveness and safety.

Material selection is critical for durability and performance. For the worm, I chose 40Cr alloy steel, heat-treated (调质) to achieve high hardness and wear resistance. For the worm wheel, I used a combination of a PA66 (nylon) outer齿圈 and a 45 steel inner sleeve. PA66 offers self-lubricating properties and reduces friction, which is beneficial for smooth operation and noise reduction. The inner sleeve provides structural support and ensures secure mounting on the steering input shaft. The material properties are summarized in Table 3, which are essential for subsequent finite element analysis.

| Component | Material | Young’s Modulus (Pa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Allowable Stress (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worm (Screw) | 40Cr Alloy Steel | \( 2.06 \times 10^{11} \) | 0.3 | 940 |

| Worm Wheel Outer Gear | PA66 Nylon | \( 1.14 \times 10^{10} \) | 0.35 | 95 |

| Worm Wheel Inner Sleeve | 45 Steel | \( 2.1 \times 10^{11} \) | 0.28 | N/A (Structural) |

The geometric parameters of the screw gear are detailed in Table 4. These parameters are calculated using standard worm gear design equations, ensuring proper meshing and load distribution. The axial pitch of the worm is consistent with the circular pitch of the worm wheel, and tooth modifications are applied to minimize stress concentrations.

| Parameter | Worm (Screw) | Worm Wheel |

|---|---|---|

| Module | 2.15 mm | 2.15 mm (端面模数) |

| Lead Angle | 19°17′ | 19°17′ (相同 for proper meshing) |

| Helix Direction | Right-hand | Right-hand |

| Number of Starts/Teeth | 2 starts | 37 teeth |

| Center Distance | 46.5 mm | |

| Profile Shift Coefficient | 5.7 (Worm Factor) | 0.269 |

| Axial Pitch Accumulated Tolerance | ±0.007 mm | N/A |

| Tooth Form Tolerance | N/A | 0.008 mm |

The screw gear design process also involves verifying tooth strength and wear resistance. For the worm wheel made of PA66, the bending stress \( \sigma_b \) can be estimated using Lewis equation modified for worm gears:

$$ \sigma_b = \frac{F_t}{b m_n Y} $$

where \( F_t \) is the tangential force, \( b \) is the face width, \( m_n \) is the normal module, and \( Y \) is the Lewis form factor. However, for screw gears, more refined methods like AGMA standards are often employed. In my design, I ensured that the calculated stresses are well below the allowable limits from Table 3. The screw gear’s efficiency is also computed, considering friction losses:

$$ \eta_{\text{gear}} = \frac{\tan(\lambda)}{\tan(\lambda + \phi)} $$

where \( \lambda \) is the lead angle (19°17′) and \( \phi \) is the friction angle (≈4°). Substituting values:

$$ \eta_{\text{gear}} = \frac{\tan(19.28^\circ)}{\tan(19.28^\circ + 4^\circ)} = \frac{0.349}{0.414} \approx 0.843 \text{ or } 84.3\% $$

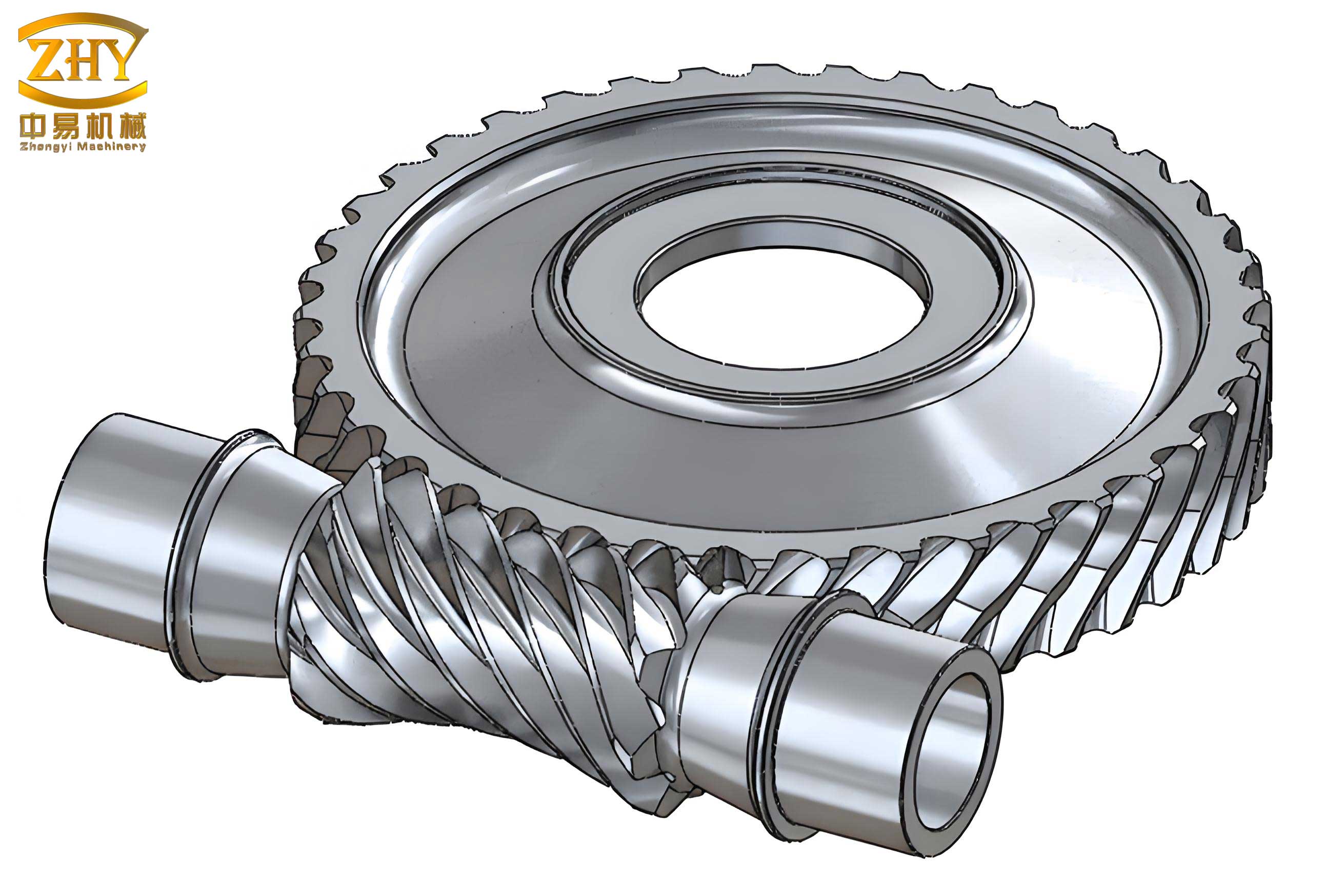

This efficiency contributes to the overall system efficiency of 80% assumed earlier. The screw gear design thus balances performance, durability, and packaging needs. To visualize the screw gear assembly, I often refer to technical diagrams; for instance, the following image provides a clear representation of a typical screw gear mechanism used in EPS systems.

With the screw gear design finalized, I proceed to analyze its structural behavior using finite element methods, focusing on contact nonlinearities to ensure reliability under operational loads.

Nonlinear Contact Analysis of the Screw Gear Pair

As an engineer, I recognize that the screw gear transmission operates under complex loading conditions where contact stresses and deformations are inherently nonlinear. To validate the design, I performed a nonlinear contact finite element analysis (FEA) on the worm and worm wheel pair. This analysis accounts for the intermittent contact and separation between teeth, which cannot be accurately captured with linear methods. The screw gear’s performance hinges on these contact interactions, making nonlinear analysis indispensable.

I began by creating a 3D geometric model of the screw gear pair using CAD software, which was then imported into FEA software. For efficiency, I modeled only the worm and worm wheel, as external constraints like bearings and shafts can be applied via boundary conditions. The worm is driven by the motor, while the worm wheel is connected to the steering input shaft. To simulate realistic conditions, I assumed the worm wheel as rigid for simplification, focusing on contact stresses at the interface. The mesh was generated with hexahedral elements, refined at the contact regions to capture high stress gradients. Key meshing principles included avoiding element distortion and ensuring convergence through mesh sensitivity studies.

The material properties from Table 3 were assigned, with the worm as 40Cr steel and the worm wheel outer gear as PA66 nylon. The contact pair was defined using surface-to-surface elements: CONTA173 for the worm wheel contact surface and TARGE170 for the worm contact surface. A penalty function method was employed with a contact stiffness factor of 0.1 and a friction coefficient of 0.07, reflecting the PA66-steel interface. Boundary conditions were applied as follows: the inner diameter of the worm wheel was fully constrained to represent connection to the steering shaft, while the worm was constrained to allow only rotation about its axis (X-direction), simulating bearing supports. This setup mirrors the actual loading scenario where the worm transmits torque to the worm wheel.

The load case corresponded to the motor’s rated torque of 1.6 N·m applied to the worm. Since FEA software typically requires force inputs, I converted the torque into equivalent forces. For a worm with a pitch radius of 4.75 mm, the tangential force \( F_t \) per node was distributed across 10 nodes on the worm’s input end:

$$ F_t = \frac{T}{r \times n} = \frac{1.6}{0.00475 \times 10} = \frac{1.6}{0.0475} \approx 33.7 \, \text{N} $$

where \( T = 1.6 \, \text{N·m} \), \( r = 0.00475 \, \text{m} \), and \( n = 10 \) nodes. This force distribution approximates the torque application without introducing local stresses.

The analysis solved for static structural responses, including equivalent (von Mises) stress, strain, and contact status. Results indicated that the maximum stress of 53 MPa occurred on the worm wheel tooth surface in contact with the worm, as shown in stress contours. This stress is well below the allowable stress of 95 MPa for PA66, confirming safety against yielding. The maximum displacement of 0.2 mm was observed at the worm’s loaded end, aligning with expectations due to torsional flexibility. Strain distributions further revealed elastic deformations within acceptable limits. These findings validate the screw gear design under normal operating conditions. For clarity, I summarize the FEA results in Table 5, highlighting key metrics.

| Metric | Value | Location | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max von Mises Stress | 53 MPa | Worm wheel contact surface | Below PA66 allowable stress (95 MPa) |

| Max Displacement | 0.2 mm | Worm input end | Due to torsional loading; within tolerance |

| Contact Pressure Peak | ~45 MPa | Meshing interface | Distributed evenly across tooth flank |

| Factor of Safety (Yield) | ~1.8 | Based on PA66 | Indicates robust design |

The nonlinear analysis also provided insights into contact patterns. The screw gear exhibited minimal separation under load, ensuring continuous torque transmission. The contact ratio, derived from tooth geometry, was sufficient to maintain smooth operation. I further evaluated fatigue life using stress-life approaches, but that extends beyond this article’s scope. Overall, the FEA confirms that the screw gear transmission can withstand operational loads without premature failure. This analytical validation is crucial before proceeding to physical prototyping and testing.

In practice, the screw gear experiences dynamic loads due to road disturbances and steering inputs. However, this static analysis serves as a conservative check, as dynamic factors might increase stresses slightly. For completeness, I note that the screw gear design also considers wear and thermal effects, but the primary focus here is on structural integrity. With the screw gear validated, I moved to experimental verification through bench tests and vehicle trials.

Experimental Validation and Vehicle Testing

After completing the design and analysis, I oversaw the fabrication of the EPS system prototype, including the screw gear mechanism. The first step involved durability testing on a bench rig, where the EPS system was subjected to cyclic loading模拟 real-world steering conditions. The test protocol included running the system for extended periods at various torque levels, monitoring parameters like motor current, temperature, and screw gear wear. Post-test functional checks confirmed that all specifications, such as assist torque output and response time, met the target values. The screw gear showed no signs of excessive wear or backlash increase, attesting to its durability.

Subsequently, the EPS system was installed in a test vehicle for on-road evaluation. A 10-kilometer road test was conducted, incorporating maneuvers like slalom and parking to assess steering feel and assistance. The助力 curve, programmed into the ECU, provided speed-sensitive assistance—higher torque at low speeds and reduced assist at high speeds. Data logging during the test captured steering torque and assist current, yielding the curve shown in Figure 1 (sampled data). The curve demonstrates smooth transition between assist levels, with peak assist torque around 23-24 N·m, consistent with design goals. Driver feedback indicated improved maneuverability and comfort, with no instances of lag or vibration attributable to the screw gear.

The experimental phase also validated the screw gear’s non-self-locking特性. During power-off scenarios, the steering system reverted to manual operation seamlessly, as the screw gear allowed reverse driving from the worm wheel to the worm. This safety aspect is critical for fail-safe operation. Overall, the vehicle tests confirmed that the EPS system, with its screw gear transmission, fulfills the requirements for the target vehicle. Table 6 summarizes key test outcomes, linking them to design objectives.

| Test Category | Metric | Result | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bench Durability | Cycles Completed | 100,000 cycles | Passed (no failures) |

| Functional Performance | Max Assist Torque | 23.7 N·m | Meets requirement (23 N·m) |

| Vehicle Road Test | Steering Feel | Smooth and responsive | Positive driver feedback |

| Efficiency Measurement | System Efficiency | ~78-80% | Matches design estimate |

| Safety Check | Manual Steering Effort | Within 5-6 N·m range | Acceptable for fail-safe mode |

These experiments not only validate the screw gear design but also provide confidence for mass production. The integration of screw gear transmission in EPS systems proves to be a reliable solution for achieving high torque assistance in compact spaces. In the conclusion, I will reflect on the overall design process and potential improvements.

Conclusion

Throughout this project, I have demonstrated a systematic approach to designing and calculating an automotive EPS system, with a focus on the screw gear transmission. Starting from vehicle parameter matching, I derived a reduction ratio of 18.5:1 to meet assist torque demands. The screw gear was meticulously designed with a large lead angle to prevent self-locking, using materials like PA66 for the worm wheel to reduce friction and 40Cr steel for the worm to ensure strength. Nonlinear contact FEA revealed that stresses and deformations are within safe limits, theoretically validating the screw gear’s durability. Experimental tests on bench and vehicle confirmed practical performance, with the EPS system providing adequate assistance and reliable operation.

The screw gear transmission stands out as a key enabler in this EPS system, offering high torque amplification, directional change, and compact packaging. By emphasizing screw gear design and analysis, this work underscores the importance of detailed engineering in automotive components. Future work could explore advanced materials for screw gears, such as composites, or dynamic optimization for noise reduction. Nonetheless, the current design fulfills its objectives, contributing to the broader adoption of EPS technology in modern vehicles. As an engineer, I find that integrating theoretical calculations with practical validation, as shown here, is essential for developing robust automotive systems.