As an engineer focused on the design and validation of vehicle steering systems, I often engage in the detailed development of Electric Power Steering (EPS) systems. The core of this work involves the precise matching of system parameters, the mechanical design of the reduction gearbox, and the rigorous analysis of its components, particularly the **screw gears**. These **screw gears** are critical for torque amplification and motion conversion. This article details the first-principles design and verification process for an EPS system tailored to a specific vehicle platform, with a significant emphasis on the engineering of its **screw gear** pair and a sophisticated nonlinear contact finite element analysis to ensure reliability.

Introduction to EPS Architecture and Operating Principle

Modern automotive steering systems have evolved significantly from traditional hydraulic power steering. The advent of Electric Power Steering (EPS) offers substantial advantages, including improved fuel economy by eliminating the engine-driven hydraulic pump, enhanced packaging flexibility, and the ability to implement advanced steering features like speed-dependent assist and active return. An EPS system is primarily composed of several key components: a steering torque/angle sensor, an electronic control unit (ECU), a power-assisted electric motor, and a reduction gear mechanism. In many designs, including the one discussed here, the reduction mechanism utilizes a **screw gear** set—a worm and worm wheel arrangement—due to its compact size and high reduction ratio capability.

The operational logic is straightforward yet elegant. When the driver applies torque to the steering wheel, the torque sensor measures this input. This signal, along with vehicle speed and often engine speed data, is sent to the ECU. The ECU’s internal algorithms, programmed with a specific “assist curve,” calculate the required assistance torque. The ECU then commands the electric motor to deliver this torque. The motor’s output is transmitted through the reduction **screw gears** to the steering mechanism (either the steering column or the rack), thereby reducing the physical effort required from the driver. The assist curve ensures maximum assistance during low-speed maneuvers like parking and gradually reduces assistance at higher speeds to maintain vehicle stability and driver feel. The system’s fail-safe operation, where assistance is cut off in case of a critical fault, reverts the steering to manual mode.

System Parameter Matching and Derivation

The foundational step in EPS development is matching the system’s performance to the target vehicle’s requirements. This involves calculating the necessary assist torque and subsequently sizing the motor and reduction ratio. For the vehicle platform in question, the key parameters were established as follows:

| Vehicle Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Curb Weight | 1420 kg |

| Front Axle Load | 950 kg |

| Maximum Vehicle Speed | 180 km/h |

Through physical testing, the maximum steering resistance torque at the front wheels under full load conditions was measured to be approximately $T_{resist} = 28 \text{ N·m}$. To maintain an acceptable level of steering feedback or “feel” for the driver, a nominal steering wheel torque of $T_{driver} \approx 5-6 \text{ N·m}$ is typically required. Therefore, the EPS system must provide an assist torque, $T_{assist}$, to overcome the difference:

$$ T_{assist} = T_{resist} – T_{driver} \approx 28 – 5.5 = 22.5 \text{ N·m} $$

Based on cost and availability, a 170W brushed DC motor was selected for this application. Its rated specifications are: Rated Torque $T_{motor} = 1.6 \text{ N·m}$ and Rated Current $I_{motor} = 30 \text{ A}$. The overall efficiency of the EPS system, accounting for losses in the motor, gears, and bearings, is estimated at $\eta_{sys} = 80\%$.

The required gear reduction ratio $i$ can be calculated to ensure the motor can provide the necessary assist torque:

$$ T_{assist} = T_{motor} \times i \times \eta_{sys} $$

$$ i = \frac{T_{assist}}{T_{motor} \times \eta_{sys}} = \frac{22.5}{1.6 \times 0.8} \approx 17.6 $$

Considering a design margin and standardization of gear parameters, a final reduction ratio of $i = 18.5:1$ was chosen. This yields a theoretical maximum assist capability of:

$$ T_{assist\_max} = 1.6 \times 18.5 \times 0.8 = 23.7 \text{ N·m} $$

This value comfortably exceeds the calculated requirement of 22.5 N·m. Given the packaging constraints requiring installation in the vehicle’s front compartment, a Pinion-type EPS (P-EPS) architecture was adopted. The finalized system matching parameters are summarized below.

| System Component | Specification / Parameter |

|---|---|

| Motor | 170W Brushed DC, 30A |

| Torque Sensor | Contact-type Potentiometer (5V supply) |

| ECU | Max Output Current: 35A |

| Reduction Mechanism | **Screw Gears**, Ratio = 18.5:1 |

| Environmental Protection | IP67 |

Detailed Design of the Screw Gear Reduction Mechanism

With the system ratio defined, the detailed design of the **screw gear** pair (worm and worm wheel) commences. For EPS applications, these components have unique requirements distinct from standard industrial **screw gears**. The most critical requirement is that the **screw gears** must be non-backdrivable for safety under normal assist operation, yet they must allow for manual steering (worm wheel driving the worm) in the event of a power failure. This necessitates a careful design of the worm’s lead angle $\gamma$ to balance efficiency, self-locking tendency, and manual steering force. A relatively large lead angle is chosen to reduce the friction angle’s influence and prevent self-locking, ensuring the driver can overcome the gear friction to steer manually if needed.

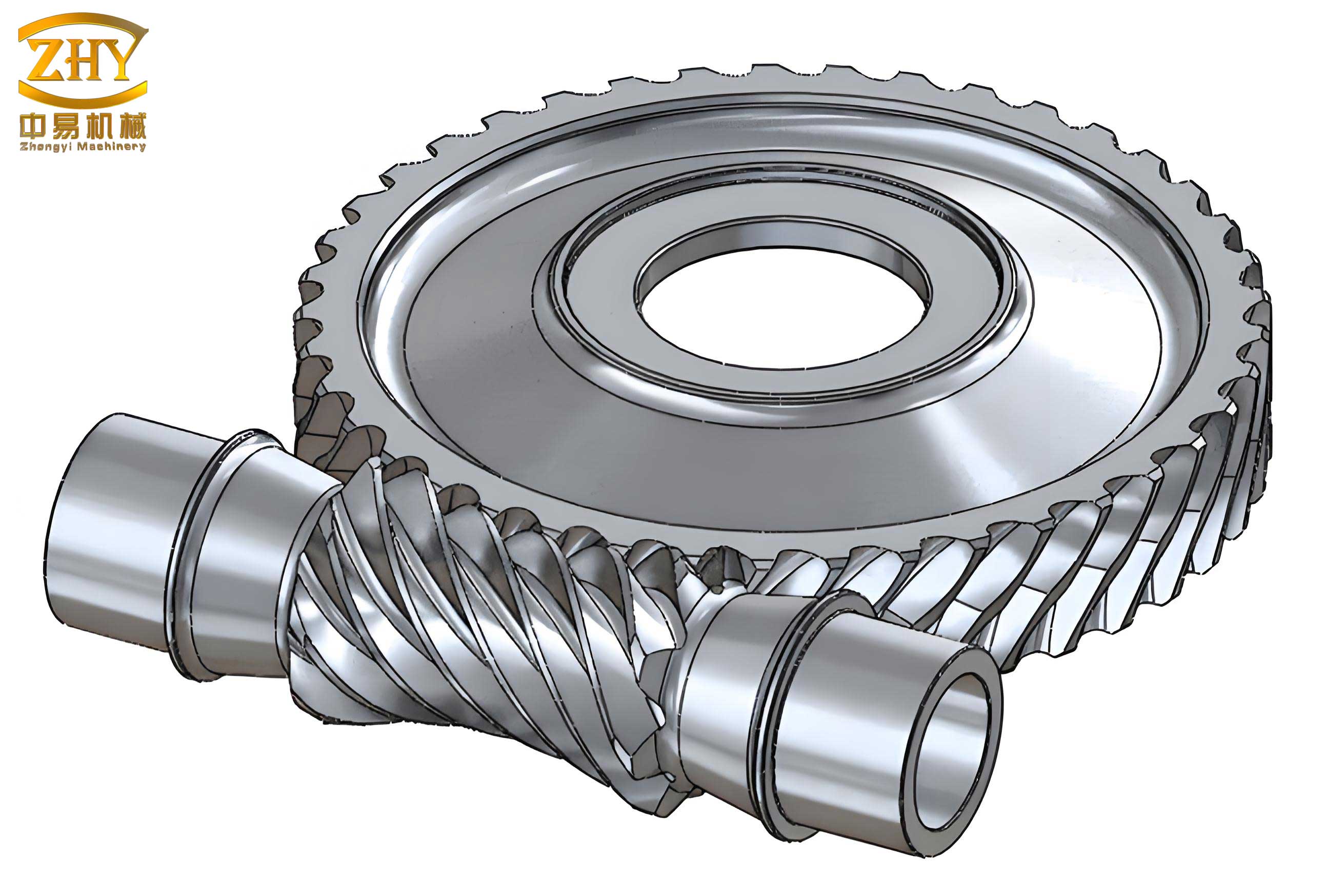

Material selection is paramount for performance and durability. The worm, as the primary driving element and subject to higher contact stresses, is manufactured from 40Cr alloy steel, heat-treated (quenched and tempered) to achieve high surface hardness and core toughness. The worm wheel presents an interesting composite design. The inner hub is made from 45# steel for strength and precise mounting. The external gear teeth, which are in sliding-rolling contact with the worm, are made from engineering plastic PA66 (Nylon 66). This material offers excellent wear characteristics, inherent lubricity, reduces friction and noise, and contributes to smoother operation. The basic geometric parameters for the **screw gear** pair were calculated and are listed in the following table.

| Parameter | Worm (Driver) | Worm Wheel (Driven) |

|---|---|---|

| Module (m) | 2.15 mm (Axial) | 2.15 mm (Transverse) |

| Lead Angle ($\gamma$) | 19° 17′ | 19° 17′ |

| Hand of Spiral | Right-hand | Right-hand |

| Number of Threads / Teeth | $Z_1 = 2$ | $Z_2 = 37$ |

| Center Distance (a) | 46.5 mm | |

| Diameter Factor (q) | 5.7 | – |

| Profile Shift Coefficient (x) | – | 0.269 |

| Reduction Ratio (i) | $i = Z_2 / Z_1 = 37 / 2 = 18.5$ | |

The lead angle is crucial and is derived from the worm’s diameter and lead. For a multi-start worm, the lead $L$ is given by $L = \pi \cdot m \cdot Z_1$. The relationship between lead angle, lead, and pitch diameter $d_1$ is:

$$ \tan(\gamma) = \frac{L}{\pi d_1} = \frac{m Z_1}{d_1} $$

Given the chosen module, number of starts, and diameter factor ($q = d_1 / m$), we can verify: $d_1 = q \cdot m = 5.7 \times 2.15 \approx 12.255 \text{ mm}$. Therefore, $\gamma = \arctan(m Z_1 / d_1) = \arctan(2.15 \times 2 / 12.255) \approx \arctan(0.351) \approx 19.3°$, confirming the specified value.

Nonlinear Contact Finite Element Analysis of the Screw Gears

While standard gear design calculations provide a foundation, the complex contact conditions between the worm and the polymer worm wheel necessitate a more advanced analysis. Linear static Finite Element Analysis (FEA) is insufficient because the contact between the **screw gears** is inherently nonlinear—the contact area changes with load, and materials may exhibit nonlinear behavior. A nonlinear contact FEA was performed to accurately predict stress distribution, contact pressure, and deformation under operational load.

Finite Element Model Development

The 3D CAD models of the worm and worm wheel were imported into a commercial FEA software suite. To optimize computational efficiency while maintaining accuracy for the region of interest (the contact zone), the following modeling strategies were employed:

- Geometry Simplification: Only half of the worm wheel model was analyzed, exploiting symmetry relative to the plane of action. This significantly reduces the number of elements without sacrificing result validity for the contact region.

- Mesh Generation: A structured hexahedral mesh was primarily used for its numerical efficiency and accuracy. The mesh was heavily refined in the anticipated contact regions on both the worm thread and the worm wheel teeth to capture the high stress gradients and potential deformation accurately. An example of the meshed **screw gear** assembly is conceptually represented in the analysis setup.

- Material Properties: The material models were defined with linear elastic properties for the initial analysis. The properties used are summarized below.

| Component | Material | Young’s Modulus (E) | Poisson’s Ratio ($\nu$) | Yield/Tensile Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worm | 40Cr Steel | 2.06e5 MPa | 0.30 | ≥ 940 MPa |

| Worm Wheel Hub | 45# Steel | 2.10e5 MPa | 0.28 | – |

| Worm Wheel Teeth | PA66 Polymer | 11400 MPa | 0.35 | 95 MPa (Tensile) |

Defining Contacts and Boundary Conditions

This is the most critical step in a nonlinear contact analysis. The interaction between the worm and worm wheel teeth surfaces was modeled using a surface-to-surface contact pair.

- Contact Pair: The threads of the worm were designated as the “target” surface (TARGE170 element type), and the flanks of the worm wheel teeth were designated as the “contact” surface (CONTA173 element type). This is appropriate as the worm surface is harder (steel) and the worm wheel is softer (polymer).

- Contact Algorithm: The Augmented Lagrange method was selected. It is robust for handling problems involving friction and separation. A friction coefficient of $\mu = 0.07$ was defined between the steel and PA66 surfaces.

- Contact Stiffness: The normal contact stiffness factor was carefully adjusted to 0.1 to balance solution convergence and physical accuracy, preventing excessive penetration while maintaining numerical stability.

The boundary conditions simulate the actual mounting and loading:

- Worm Wheel Constraints: The inner bore surface of the worm wheel’s steel hub was fully constrained (all degrees of freedom fixed). This represents the wheel being rigidly connected to the steering column input shaft.

- Worm Constraints: The worm shaft was supported at its bearing locations. All translational degrees of freedom were constrained at these points, allowing only rotation about its own axis (the X-axis in the model). This correctly simulates the support provided by two bearing sets.

- Loading: The motor’s rated torque of $T_{motor} = 1.6 \text{ N·m}$ was applied to the worm. Since FEA software typically applies nodal forces, the torque was converted into an equivalent set of tangential forces on nodes at the worm’s drive end. For a nominal pitch radius $r_{worm} \approx 4.75 \text{ mm}$ and applying 10 equivalent forces, the force magnitude per node $F_{node}$ is:

$$ F_{node} = \frac{T_{motor}}{r_{worm} \times N_{nodes}} = \frac{1.6}{0.00475 \times 10} \approx 33.7 \text{ N} $$

Analysis Results and Interpretation

The nonlinear static analysis was solved iteratively. The primary results of interest were the von Mises stress distribution and the total deformation.

- Stress Distribution: The maximum von Mises stress was found to be approximately $\sigma_{max} \approx 53 \text{ MPa}$. This stress concentration occurred on the root and contact flank of the PA66 worm wheel tooth engaged with the worm. This is expected, as this region undergoes combined bending and contact (Hertzian) stresses. Crucially, this peak stress is well below the tensile strength of PA66 (95 MPa), providing a comfortable safety factor under the rated motor torque condition.

- Deformation: The maximum total deformation was about $u_{max} \approx 0.2 \text{ mm}$, located at the free end of the worm shaft where the driving force is applied. This minor deflection is structurally acceptable and aligns with expectations.

- Contact Pressure: The analysis also provides the contact pressure distribution along the tooth flank. The pressure profile was elliptical, characteristic of Hertzian contact, with a peak value that remained within the allowable limits for PA66 against hardened steel, indicating minimal risk of plastic deformation or excessive wear under design loads.

It is important to note that this analysis represents a “worst-case” static scenario with the worm wheel fully fixed. In real dynamic operation, the wheel experiences a resisting torque rather than a fixed constraint, which would likely result in slightly lower stress magnitudes in the wheel teeth. Therefore, the FEA results provide strong theoretical validation that the **screw gear** design is robust and reliable for its intended service life.

Physical Prototype Testing and Vehicle Validation

Theoretical design and simulation must be followed by physical validation. The EPS system, incorporating the designed **screw gears**, was first subjected to rigorous durability testing on a dedicated steering bench rig. The system underwent thousands of high-torque cycles, simulating years of severe usage. Post-durability functional tests confirmed that all parameters, including assist torque output, sensor accuracy, and ECU response, remained within specification.

Subsequently, the system was installed in a prototype vehicle for real-world road testing. A critical evaluation maneuver was the “sinusoidal” or “snake” test, which assesses steering response, feel, and the effectiveness of the speed-dependent assist. The assist characteristic curve, mapping steering wheel torque to assist motor current, was sampled during these tests. The curve demonstrated a progressive and predictable assist, providing strong assistance at low steering torques (for parking ease) and gradually saturating at higher torques, ensuring stability. The driver reported a natural and well-balanced steering feel across the speed range, confirming the successful integration of the parameter matching, **screw gear** design, and control logic.

Conclusion

The successful development of an automotive EPS system requires a systematic engineering approach, from initial vehicle parameter matching to detailed component design and final validation. This article detailed the process for a specific vehicle application, culminating in the design of an 18.5:1 reduction **screw gear** pair. The unique requirements for EPS **screw gears**, particularly the need for controlled non-backdrivability and low friction, were addressed through careful geometric parameter selection and material pairing (hardened steel worm against polymer worm wheel).

The application of nonlinear contact Finite Element Analysis proved to be an invaluable tool. It moved beyond classical gear formulas to provide a detailed understanding of the stress state and deformation within the complex interacting **screw gears**. The analysis confirmed that the design operated within safe mechanical limits under the rated load. Finally, bench durability tests and on-vehicle road trials provided empirical evidence that the EPS system met all functional, durability, and driver feel requirements. This integrated process of calculation, simulation, and testing ensures the delivery of a reliable and high-performance power steering system.