In the field of precision motion control and robotics, the strain wave gear, commonly known as the harmonic drive, stands out as a critical component due to its compact size, high reduction ratio, excellent efficiency, and superior accuracy. As a core element in industrial robots and precision positioning systems, the performance of a strain wave gear directly impacts the overall system’s capabilities. To achieve卓越的传动性能, the gear must meet stringent requirements in angular transmission accuracy, strength, and stiffness. Central to fulfilling these demands is the design of the tooth profile. In this article, I will elaborate on a design methodology for a non-interfering and wide-range meshing tooth profile based on curve mapping theory, which significantly enhances the meshing characteristics of strain wave gears.

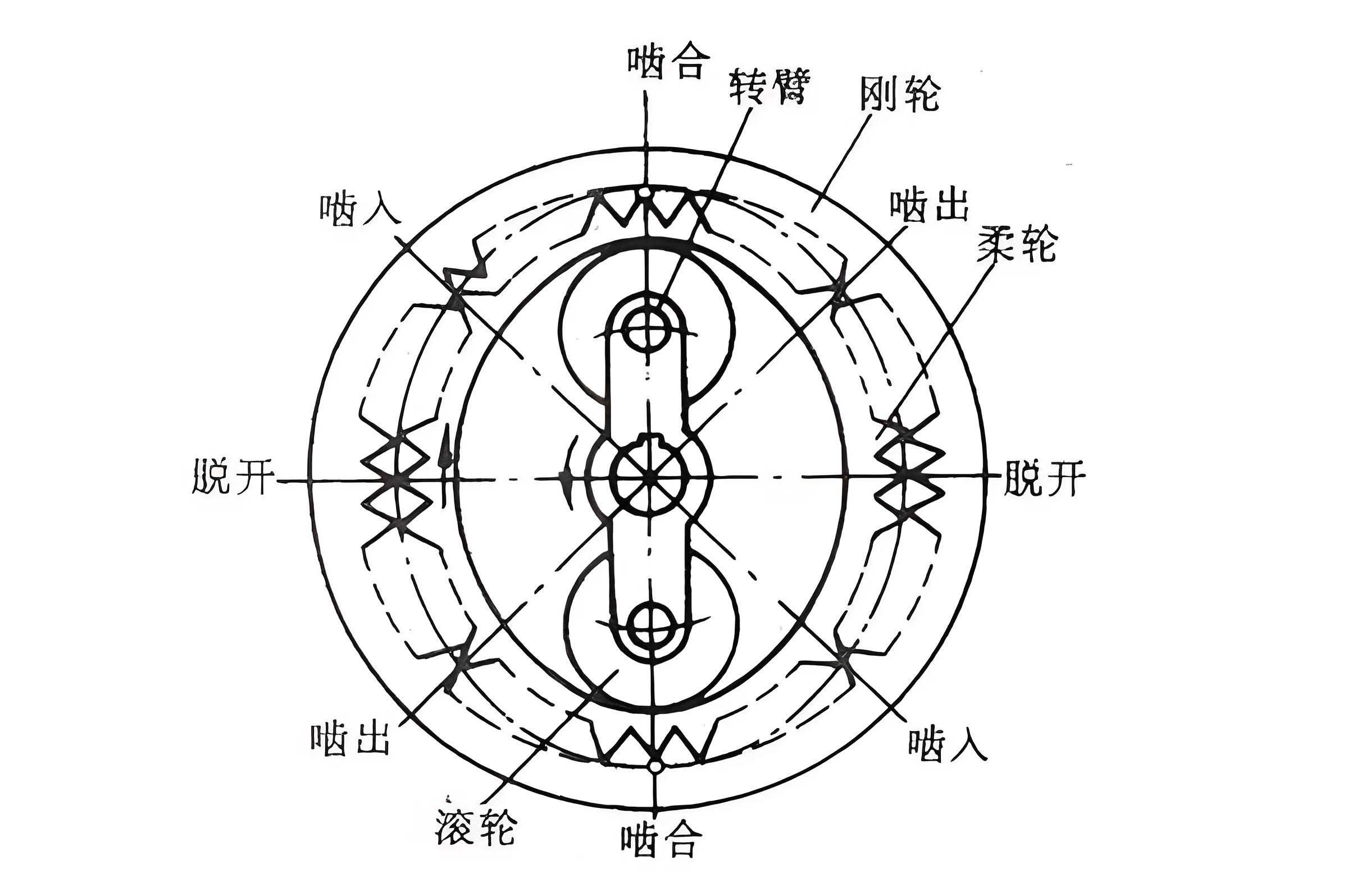

The fundamental principle behind this advanced tooth profile design is curve mapping theory. This geometric approach ensures continuous contact between the flexspline and circular spline teeth throughout the engagement cycle without interference, thereby maximizing the number of simultaneously meshing teeth. The subsequent sections will delve into the theoretical foundation, the derivation of an approximate profile, necessary corrections, and the final tooth profile equations. Throughout this discussion, the term “strain wave gear” will be frequently emphasized to underscore its relevance and application.

Curve mapping theory provides a geometric framework for generating conjugate tooth profiles. Consider the neutral curve of the flexspline, which deforms under the action of the wave generator. Points on this neutral curve follow specific trajectories during operation. Let the trajectory of a point on the neutral curve be denoted as curve $a_0b_0$. Through a geometric mapping process—specifically, a scaling transformation with a factor of 0.5—the corresponding tooth profile on the circular spline, curve $a_1b_1$, is derived. Subsequently, rotating curve $a_1b_1$ by 180° around point $a_1$ yields the tooth profile on the flexspline, curve $a_2b_2$. This mapping ensures that during motion, corresponding points on the flexspline and circular spline profiles coincide and are tangent to each other, guaranteeing continuous contact and non-interference. The mathematical essence of this mapping can be summarized as follows: for any point $c_0$ on the neutral curve, its mapped points $c_1$ on the circular spline and $c_2$ on the flexspline maintain tangency throughout the gear’s operation. This property is crucial for achieving a wide meshing range in strain wave gears.

To translate this theory into a practical tooth profile, we begin with the motion law of points on the flexspline’s neutral curve. When a cosine cam wave generator is employed, the radial displacement $\omega$ and circumferential displacement $\upsilon$ of a point on the neutral curve are given by:

$$

\upsilon = -0.5m \cdot \sin 2\theta

$$

$$

\omega = m \cdot \cos 2\theta

$$

Here, $m$ represents the neutral curve modulus, and $\theta$ is the rotation angle of the non-deformed end of the flexspline. Assuming both the flexspline and circular spline are idealized as racks, the relative trajectory of a point on the flexspline’s neutral curve with respect to the circular spline can be expressed in parametric form:

$$

x_1 = 0.5m \cdot (2\theta – \sin 2\theta)

$$

$$

y_1 = m \cdot (1 – \cos 2\theta)

$$

Applying curve mapping theory and appropriate coordinate transformations, the equations for the approximately designed upper tooth profile (for both gears) are derived:

$$

x_0 = m_g [0.25\pi – (\pm \tau)] – 0.25m \cdot (2\theta – \sin 2\theta)

$$

$$

y_0 = 0.5m \cdot (1 – \cos 2\theta)

$$

In these equations, $m_g$ is the gear module, and $\tau$ is the tooth thickness variation coefficient. The sign $\pm$ accounts for the left and right flanks of the tooth. This approximate profile, however, is based on the rack assumption and does not account for real-world geometric complexities inherent in cylindrical strain wave gears.

In actual strain wave gear configurations, two significant factors necessitate correction of the approximate profile: the inclination of the flexspline teeth during meshing and the deviation of the true motion trajectory from the rack model. To address these, we must first establish the coordinate relationships between the flexspline and circular spline. Consider a fixed coordinate system $OXY$ attached to the wave generator, with the $Y$-axis aligned with the generator’s major axis. Two moving coordinate systems, $O_F X_F Y_F$ attached to the flexspline and $O_C X_C Y_C$ attached to the circular spline, are defined. Key angular relationships are as follows:

- The rotation of the $Y_C$ axis relative to the $Y$ axis: $\Phi_1 = (Z_F / Z_C) \cdot \theta$

- The rotation of the vector $\rho$ (from $O$ to $O_F$) relative to the $Y$ axis: $\Phi_2 = \theta – 0.5 \cdot m \cdot \sin 2\theta / r_n$

- The rotation of the $Y_F$ axis relative to the vector $\rho$: $\mu = \arctan\{2 \cdot m \cdot \sin 2\theta / (r_n + \omega)\}$

- The total inclination angle of the flexspline tooth: $\Phi = \gamma + \mu$, where $\gamma = \Phi_2 – \Phi_1$

Here, $Z_F$ and $Z_C$ are the number of teeth on the flexspline and circular spline, respectively, and $r_n$ is the radius of the neutral curve before deformation. The correction terms are then calculated. The correction for flexspline tooth inclination, $g_1$, is given by:

$$

g_1 = h \cdot \Phi

$$

where $h$ is a distance parameter defined as:

$$

h = 0.5 \cdot t + m_g \cdot (h_a^* + c^*) + f

$$

and $f$ is:

$$

f = 0.5 \cdot m \cdot [1 – \cos 2\theta] – 0.5 \cdot \tan \theta \cdot \{m_g \cdot [0.25\pi – (\pm \tau)] – 0.25m \cdot (2\theta – \sin 2\theta)\}

$$

In these expressions, $t$ is the rim thickness of the flexspline, $h_a^*$ is the addendum coefficient, and $c^*$ is the clearance coefficient. The correction for the change in motion trajectory, $g_2$, is derived as:

$$

g_2 = \{0.5 \cdot m \cdot [2\theta – \sin 2\theta] – x_N\} + 0.5 \cdot \tan \theta \cdot \{y_N – m[1 – \cos 2\theta]\}

$$

with $x_N$ and $y_N$ representing the actual trajectory coordinates:

$$

x_N = (r_n + m \cdot \cos 2\theta) \cdot \sin \gamma

$$

$$

y_N = (r_n + m) – (r_n + m \cdot \cos 2\theta) \cdot \cos \gamma

$$

Integrating these corrections, the final equations for the upper tooth profile of the strain wave gear are obtained:

$$

x = m_g[0.25\pi – (\pm \tau)] – 0.25m \cdot (2\theta – \sin 2\theta) – 0.5(g_1 – g_2)

$$

$$

y = 0.5m \cdot (1 – \cos 2\theta)

$$

The lower tooth profile can be designed arbitrarily, often as a simple curve like a straight line or circular arc, provided it does not cause interference during meshing. This flexibility aids in manufacturing practicality while maintaining the non-interference characteristic essential for strain wave gear performance.

To validate the efficacy of this tooth profile design, let us consider a numerical example. Using the following parameters typical for a strain wave gear: $m = 0.5$, $Z_F = 200$, $Z_C = 202$, $t = 1$, $h_a^* = 0.8$, $c^* = 0.25$, and $\tau = 0.2$, we can plot the tooth profiles. The flexspline profile (curve $f$) and circular spline profile (curve $c$) exhibit continuous tangency throughout the engagement cycle. Simulations show that from initial contact to full engagement, the teeth remain in contact without any interference. This results in a significantly larger simultaneous contact ratio compared to traditional tooth profiles, such as the involute. For this design, up to 30% of the total teeth can be in contact at once, whereas conventional involute profiles in strain wave gears typically achieve less than 15% even under load. This increase directly translates to substantial improvements in rigidity, transmission accuracy, and torque capacity—often exceeding 30% enhancement. Such performance gains are crucial for advanced applications where strain wave gears are deployed.

The advantages of this non-interfering wide-range tooth profile are multifaceted. Firstly, the increased number of simultaneously meshing teeth distributes the load more evenly, reducing stress concentrations and wear. Secondly, the continuous contact minimizes backlash and improves positional accuracy, which is vital for precision robotics. Thirdly, the design inherently enhances torsional stiffness, leading to better dynamic response. These benefits collectively make the strain wave gear more reliable and efficient in demanding environments.

To further illustrate the design parameters and their impacts, the table below summarizes key variables used in the tooth profile derivation for strain wave gears:

| Symbol | Description | Typical Range/Value |

|---|---|---|

| $m$ | Neutral curve modulus | 0.3 – 1.0 mm |

| $m_g$ | Gear module | 0.1 – 0.5 mm |

| $Z_F$ | Number of teeth on flexspline | 100 – 300 |

| $Z_C$ | Number of teeth on circular spline | $Z_F + 2$ (common) |

| $r_n$ | Neutral curve radius before deformation | Depends on gear size |

| $t$ | Flexspline rim thickness | 0.5 – 2.0 mm |

| $h_a^*$ | Addendum coefficient | 0.6 – 1.0 |

| $c^*$ | Clearance coefficient | 0.2 – 0.3 |

| $\tau$ | Tooth thickness variation coefficient | 0.1 – 0.3 |

| $\theta$ | Rotation angle parameter | $0$ to $\pi/2$ for half-cycle |

Another table comparing the performance characteristics of the proposed tooth profile versus a traditional involute profile in strain wave gears highlights the advancements:

| Performance Metric | Proposed Non-Interfering Profile | Traditional Involute Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Simultaneous Contact Ratio | Up to 30% of total teeth | Typically < 15% |

| Transmission Accuracy | High (minimized backlash) | Moderate (susceptible to backlash) |

| Torsional Stiffness | Enhanced (>30% improvement) | Standard |

| Load Distribution | More uniform | Less uniform |

| Manufacturing Complexity | Moderate (requires precise correction) | Lower (well-established) |

The mathematical foundation of this design can be expanded by considering the kinematic relationships in greater detail. The wave generator’s action induces an elliptical deformation in the flexspline, which can be modeled using deformation functions. For a cosine cam, the radial deformation $w$ at any angular position $\phi$ on the flexspline is given by $w = w_0 \cos(2\phi)$, where $w_0$ is the maximum deformation. This directly relates to the neutral curve modulus $m$. In the context of strain wave gear design, ensuring non-interference requires that the tooth profiles satisfy the condition of envelope generation. The curve mapping approach essentially provides a method to derive the conjugate profile that is the envelope of the family of curves generated by the flexspline motion.

From a practical standpoint, the design process for strain wave gear tooth profiles involves iterative refinement. After obtaining the final profile equations, engineers must account for manufacturing tolerances and material deflections under load. Finite element analysis (FEA) is often employed to simulate the meshing behavior and validate the non-interference condition under various operating conditions. Moreover, the tooth profile can be optimized for specific criteria, such as minimizing stress concentration or maximizing efficiency, using numerical methods. For instance, the parameter $\tau$ can be adjusted to balance tooth strength and meshing smoothness. The flexibility in designing the lower flank allows for optimization of the root geometry to enhance fatigue resistance, a critical factor in the longevity of strain wave gears.

In terms of applications, the improved strain wave gear with this advanced tooth profile finds use in high-precision robotics, aerospace actuators, medical devices, and optical positioning systems. The ability to handle high torque with minimal backlash makes it ideal for robotic joints where precise motion control is paramount. Additionally, the compact design aligns with the trend towards miniaturization in modern machinery. As robotics and automation continue to advance, the demand for high-performance strain wave gears is expected to grow, driving further research into tooth profile optimization.

To delve deeper into the corrections, the inclination correction $g_1$ addresses the fact that the flexspline teeth do not remain radial during deformation; they tilt due to the circumferential displacement. This tilt angle $\Phi$ varies with $\theta$, and neglecting it would lead to premature contact loss or interference. The trajectory correction $g_2$ accounts for the circular geometry of the gears, as the rack assumption simplifies the motion to a translational path, whereas the actual relative motion involves rotation. These corrections ensure that the tooth profile is truly conjugate for cylindrical strain wave gears. The mathematical derivation of these corrections stems from coordinate transformations between the moving frames. Specifically, the position of a point on the flexspline tooth in the circular spline coordinate system must be computed accurately. The general transformation matrix approach can be used, but the presented equations provide a concise formulation tailored for strain wave gears.

Furthermore, the design methodology can be extended to other types of wave generators, such as elliptical bearings or four-roller configurations. The motion law of the neutral curve would differ, but the curve mapping theory remains applicable. For example, for a wave generator producing a more complex deformation pattern, the radial and circumferential displacements $\omega$ and $\upsilon$ would be described by different harmonic functions. The subsequent steps for profile generation and correction would follow a similar pattern, albeit with modified equations. This adaptability underscores the robustness of the curve mapping approach for strain wave gear design.

In conclusion, the design of a non-interfering wide-range tooth profile for strain wave gears, based on curve mapping theory, offers significant performance advantages. By starting from an approximate profile derived from the neutral curve trajectory and applying precise corrections for tooth inclination and motion trajectory changes, a final profile is obtained that ensures continuous, interference-free meshing. This results in a high simultaneous contact ratio, enhancing rigidity, accuracy, and torque capacity. The methodology underscores the importance of detailed geometric analysis in the development of high-performance strain wave gears. Future work may involve integrating this design with advanced manufacturing techniques like additive manufacturing for customized strain wave gears, or exploring real-time adaptive profiles that adjust to load conditions. Regardless, the pursuit of optimal tooth profiles remains central to advancing strain wave gear technology and its applications in precision engineering.