The exploitation of mineral resources faces unprecedented challenges. Easily accessible, high-grade shallow deposits are becoming increasingly depleted, leading to growing energy dependency and constraining economic development. The future of resource extraction lies in tapping into deep-seated minerals and shallow, uneven, low-grade deposits. However, conventional mining methods for these resources are often hampered by high technical complexity and prohibitive costs. Therefore, developing efficient and economical extraction technologies is paramount. Hydraulic borehole mining (HBM) technology, which utilizes high-pressure water jets to fragment ore in situ, presents a promising solution. This technique offers significant advantages, including shorter mine construction cycles, reduced environmental footprint, lower operational costs, and the ability to operate at greater depths. It shows vast potential for the development of China’s lean and deep mineral resources. As researchers in this field, we have focused on overcoming a critical limitation of traditional HBM tools.

The core process of HBM involves drilling a borehole to the target ore layer, deploying a high-pressure water jet device (a “monitor” or “gun”), using the jet’s cutting force to fragment the ore, and then lifting the resulting slurry to the surface for processing. The efficiency of rock fragmentation by the high-pressure water jet is the decisive factor for the overall mining efficiency. This process is fundamentally an interaction between the water jet and the rock, leading to its damage and breakage. Among the many factors influencing jet rock breaking, the standoff distance—the distance from the nozzle outlet to the rock surface—plays a crucial and often limiting role.

Traditional HBM tools employ a fixed nozzle. During the mining process, as the jet erodes the rock face, the cavity grows, and the effective standoff distance increases continuously. Our analysis of experimental and numerical simulation data from various sources clearly demonstrates the severe impact of increasing standoff distance, especially under submerged conditions where the jet operates within a water- or slurry-filled borehole.

As shown in the data trends, the depth of penetration and the volume of rock removed by the jet are highly sensitive to standoff distance. Typically, performance increases to an optimal point and then decreases sharply. For instance, in submerged jet experiments, the erosion depth can decrease by over 60% when the standoff increases from 2 mm to 12 mm. More critically, the volume of rock eroded often peaks at a specific optimal standoff (e.g., around 5 mm in some studies) and falls drastically beyond it. To maintain fragmentation effectiveness at larger standoffs, the required initial jet velocity increases substantially, demanding more powerful and energy-intensive pumping systems.

Therefore, the fixed nozzle in traditional tools creates a fundamental inefficiency. As mining progresses radially from the borehole, the jet quickly operates beyond its optimal standoff, leading to a rapid decline in production rate. This severely limits the effective mining radius of a single borehole, reducing overall yield and economic viability. The solution is a drilling tool with a telescopic hydraulic jet device that can actively control the standoff distance, keeping it within an optimal range as the mining cavity expands.

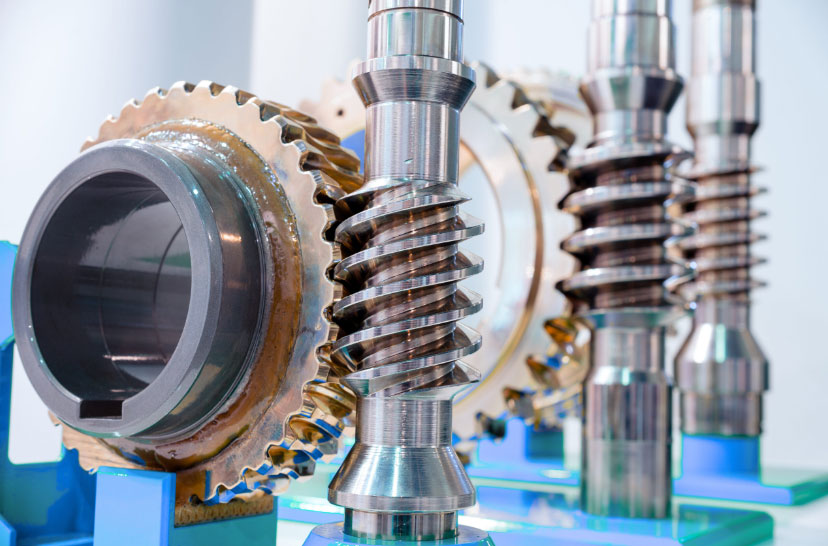

Our research group has previously developed and tested several prototype telescopic HBM tools, including mechanically controlled designs using spring collets or pawl mechanisms, and an electrically controlled single-action design. These prototypes successfully demonstrated the principle, increasing the single-hole mining diameter by several meters. Building upon this foundation, we propose a new, robust design specifically suited for shallow mining applications: a telescopic hydraulic mining tool based on a worm and worm gear drive system. This design aims for simplicity, reliability, and precise control over the extension mechanism.

The proposed telescopic drilling tool consists of three main systems: the high-pressure water delivery system, the monitor telescoping system, and the slurry removal system. The telescoping system is the innovative heart of the tool, centered around the worm and worm gear mechanism.

1. Structural Design of the Telescoping Mechanism

The core of this system is a pair of worm gears. A vertical worm shaft is mounted within the tool’s outer housing via upper and lower thrust bearings. A sliding plate is welded to the central high-pressure water pipe assembly. This sliding plate features a machined slot that houses a worm wheel, which meshes directly with the vertical worm shaft. Two guide rods, fixed at the top and bottom of the housing, pass through the sliding plate to prevent rotation and ensure it moves only vertically. The hydraulic monitor is connected to the sliding plate through a linkage system (e.g., a set of connected rods or a scissor mechanism). The rotational motion of the worm is thus converted into precise linear vertical motion of the sliding plate, which in turn drives the linkage to extend or retract the monitor.

The kinematics can be described simply. For one complete revolution of the worm, the worm wheel advances by one tooth. If the worm gear has \( N \) teeth, the linear travel \( L \) of the sliding plate per revolution of the worm is given by the lead of the worm gear system. For a single-start worm, the lead is equal to the pitch \( p \). Therefore:

$$ L = \frac{p}{N} $$

This provides a slow, controlled, and powerful linear extension, ideal for this application.

2. Working Principle and Process

The operational workflow using this tool is as follows:

- A borehole is drilled to the target depth and ore layer.

- The tool is lowered into position. The drill string rotates slowly, turning the entire tool. High-pressure water is pumped, initiating jet-based rock fragmentation. Slurry is removed via a reverse circulation system through a separate slurry pipe.

- When the slurry density indicates reduced fragmentation efficiency (signifying the standoff has become too large), the worm shaft is rotated from the surface. This can be done manually or with a simple drive mechanism. As the worm turns, the meshing worm gear causes the sliding plate to descend. This descent, through the connecting linkage, pushes the monitor outward, decreasing the standoff distance to a new optimal value. The self-locking property of the worm and worm gear pair is crucial here—once the driving force on the worm stops, the system holds its position securely, preventing unintended retraction due to water jet reaction forces or vibration.

- To retract the monitor for tool retrieval, the worm is simply rotated in the opposite direction.

The mechanical advantage and torque relationship in the worm and worm gear drive are key to its functionality. The torque required on the worm (\( T_{worm} \)) to move a load force \( F \) on the sliding plate is approximated by:

$$ T_{worm} \approx \frac{F \cdot d_{worm\_gear}}{2 \cdot \eta \cdot GR} $$

where \( d_{worm\_gear} \) is the pitch diameter of the worm gear, \( GR \) is the gear ratio (typically very high, e.g., 30:1 or more), and \( \eta \) is the efficiency of the worm gear pair. This high gear ratio allows a relatively small input torque at the worm to generate a large force for extending the monitor against potential resistance.

3. Analysis of Advantages Over Fixed-Nozzle Tools

The primary advantage is the dramatic increase in single-borehole mining area. With a designed monitor arm length of 2500 mm and a maximum extension angle of 90°, the tool can theoretically mine a cylindrical region with a radius over 2.5 meters larger than a fixed nozzle tool. More importantly, it maintains the jet’s standoff within a high-efficiency range throughout the process. We can model the potential volume increase. Assuming a borehole of depth \( H \) in the ore layer:

- For a fixed nozzle with effective radius \( R_f \), mined volume \( V_f \approx \pi R_f^2 H \).

- For the telescopic tool with a final mining radius \( R_t = R_f + \Delta R \) (where \( \Delta R \) is the arm length), volume \( V_t \approx \pi R_t^2 H \).

The volume ratio is:

$$ \frac{V_t}{V_f} \approx \left(1 + \frac{\Delta R}{R_f}\right)^2 $$

If \( R_f \) is 0.5m and \( \Delta R \) is 2.5m, the volume increases by a factor of 36. This illustrates the transformative potential of controlling standoff distance.

The worm and worm gear system provides several specific benefits:

| Feature | Benefit |

|---|---|

| Self-Locking | Prevents back-driving, securely locking the monitor position without needing a separate brake. |

| High Reduction Ratio | Allows precise, inch-by-inch control of extension using simple manual or low-power drives. |

| Continuous (Stepless) Adjustment | Enables the monitor to be positioned at any point within its range, adapting perfectly to variable rock conditions. |

| Robustness | Worm gears are durable and can operate effectively in the harsh, slurry-filled downhole environment. |

| Positive Retraction | Ensures the monitor can always be pulled back into the housing for safe tool retrieval, a critical safety feature. |

4. Design Considerations and Performance Metrics

The design of the worm and worm gear pair must account for downhole conditions. Key parameters include:

- Material Selection: The worm and worm gear must be made from wear-resistant, corrosion-resistant materials, such as hardened steel or bronze for the worm gear.

- Efficiency and Lubrication: While worm gears have lower efficiency than some drives, a well-designed, properly lubricated system is sufficient. Sealed grease chambers can be used.

- Thrust Bearing Capacity: The axial thrust on the worm shaft from the jet reaction force and the gear mesh must be supported by robust thrust bearings.

We can define a performance metric, the Standoff Control Efficiency Gain (SCEG), to quantify the improvement:

$$ SCEG = \frac{A_{telescopic}}{A_{fixed}} = \frac{\int_{0}^{R_t} f_{opt}(r) \, dr}{\int_{0}^{R_f} f_{deg}(r) \, dr} $$

where \( f_{opt}(r) \) is the high, maintained fragmentation rate profile of the telescopic tool and \( f_{deg}(r) \) is the rapidly decaying profile of the fixed tool. The SCEG is always >> 1.

In conclusion, the transition from fixed-nozzle to telescopic hydraulic mining tools represents a necessary evolution for enhancing the efficiency and economic range of HBM technology. Our proposed design, centered on a reliable worm and worm gear drive mechanism, offers a practical solution for shallow mining applications. The mechanism provides the precise, lockable, and controllable linear motion required to actively manage the critical standoff distance parameter. By doing so, it directly addresses the major limitation of traditional tools, enabling a significant expansion of the mining area per borehole. This leads to higher productivity, reduced drilling costs (fewer boreholes needed per resource block), and makes the exploitation of leaner or more challenging deposits more viable. Future work will focus on detailed mechanical design, prototyping, and controlled field trials to validate the performance and durability of this worm gear-based telescopic system under real mining conditions.