In the field of high-precision mechanical systems, the planetary roller screw assembly stands out as a critical component for converting rotational motion into linear displacement with exceptional load capacity, stability, and suitability for high-speed operations. My focus in this analysis is on the small angular movement characteristics of the planetary roller screw assembly, a scenario often encountered in practical applications such as servo systems and precision positioning. The need for accurate dynamic modeling under these conditions is paramount, as even minor elastic deformations and slip phenomena can significantly impact overall system performance. I aim to develop a comprehensive mathematical framework and validate it through finite element simulations, thereby elucidating the motion and dynamic properties of the planetary roller screw assembly during small-angle rotations. This work builds upon existing research but delves specifically into the less-explored domain of small-signal dynamics, where traditional large-angle assumptions may not hold.

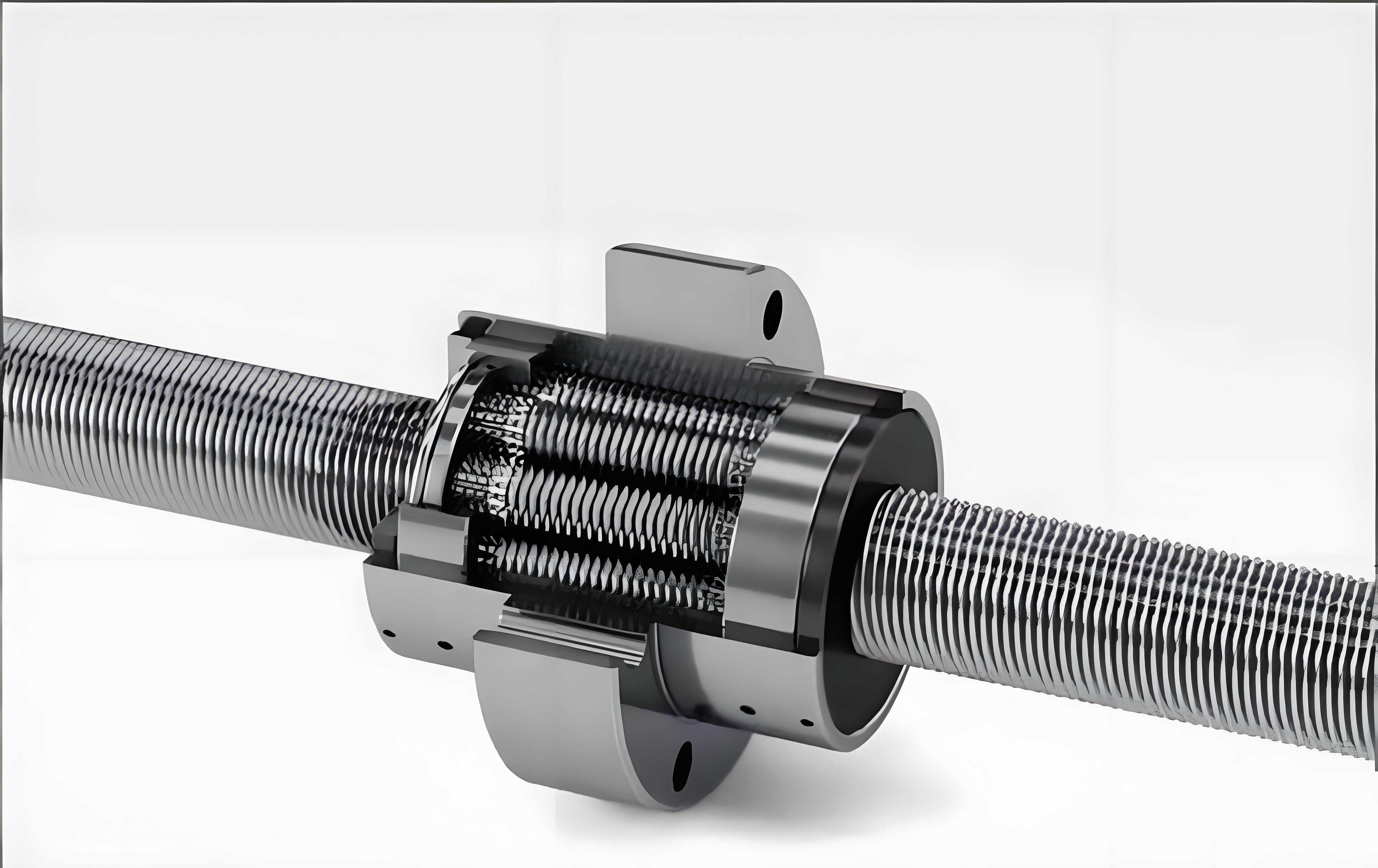

The planetary roller screw assembly consists of several key components: a screw, multiple threaded rollers, a nut, a retainer ring, and gears. In this configuration, the rollers are positioned around the screw and engage with both the screw and the nut threads, facilitating motion transmission through rolling contact rather than sliding. This design not only enhances efficiency but also distributes loads across multiple contact points, making the planetary roller screw assembly ideal for demanding applications in aerospace, medical devices, robotics, and optical instruments. For small angular movements, the axial displacement of the nut can be decomposed into two primary contributions: the elastic deformation due to Hertzian contact at the meshing interfaces and the kinematic displacement resulting from the screw’s rotation. My approach involves first establishing a mathematical model that accounts for these factors, then employing Hertz contact theory to quantify elastic deformations under varying loads, and finally deriving the transmission relationships to predict axial motion. Subsequently, I construct a finite element model of the planetary roller screw assembly to simulate its dynamic response, enabling a detailed analysis of stress distributions, displacement curves, and overall behavior under simulated operating conditions.

To model the elastic deformations in the planetary roller screw assembly, I turn to Hertz contact theory, which provides a classical solution for point contact between two elastic bodies. The assumptions underlying this theory are particularly relevant here: the contact surfaces are smooth, deformations are purely elastic and obey Hooke’s law, the contact area dimensions are small compared to the curvature radii of the bodies, and tangential friction forces are negligible. In the context of the planetary roller screw assembly, these assumptions are reasonable for small angular movements under rated loads, where plastic deformation is minimal. For a point contact subjected to a normal load \( Q \), the contact region expands into an elliptical area with semi-major axis \( a \) and semi-minor axis \( b \). These parameters are derived from the following equations:

$$ a = m_a \sqrt[3]{\frac{3Q}{E’ \sum \rho}}, \quad b = m_b \sqrt[3]{\frac{3Q}{E’ \sum \rho}} $$

where \( m_a \) and \( m_b \) are coefficients dependent on the ellipticity \( k = b/a \), \( E’ \) is the equivalent elastic modulus, and \( \sum \rho \) represents the sum of principal curvatures at the contact point. The elastic approach \( \delta \), which quantifies the deformation, is given by:

$$ \delta = \frac{K(e)}{\pi m_a} \sqrt[3]{\frac{3}{E’^2} Q^2 \sum \rho} $$

Here, \( K(e) \) and \( L(e) \) are the complete elliptic integrals of the first and second kind, respectively, with eccentricity \( e = \sqrt{1 – k^2} \). The equivalent elastic modulus \( E’ \) is calculated as:

$$ E’ = \frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{1 – \mu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1 – \mu_2^2}{E_2} \right) $$

where \( E_1, E_2 \) and \( \mu_1, \mu_2 \) are the Young’s moduli and Poisson’s ratios of the contacting materials. For the planetary roller screw assembly, I consider material properties typical of high-strength alloys, such as 42CrMo4, with an elastic modulus of 210 GPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.29 at elevated temperatures. The principal curvatures for the screw-roller and roller-nut contacts are critical inputs. Based on the geometry of the planetary roller screw assembly, these curvatures are derived as follows for the screw-roller interface:

$$ \rho_{11} = \frac{1}{R}, \quad \rho_{12} = \frac{2 \cos \lambda_r \cos \alpha}{d_{mr}}, \quad \rho_{21} = 0, \quad \rho_{22} = \frac{2 \cos \lambda_s \cos \alpha}{d_{ms} – d_{mr} \cos \alpha} $$

and for the roller-nut interface:

$$ \rho_{11} = \frac{1}{R}, \quad \rho_{12} = \frac{2 \cos \lambda_r \cos \alpha}{d_{mr}}, \quad \rho_{21} = 0, \quad \rho_{22} = -\frac{2 \cos \lambda_n \cos \alpha}{d_{mn} + d_{mr} \cos \alpha} $$

In these equations, \( R \) is the radius of curvature, \( \lambda \) denotes the lead angle, \( \alpha \) is the contact angle, and \( d_m \) represents the pitch diameter for the screw (s), roller (r), and nut (n). To facilitate calculations, I compile the basic structural parameters of the planetary roller screw assembly in Table 1.

| Component | Lead (mm) | Number of Threads | Contact Radius R (mm) | Pitch Diameter d_m (mm) | Lead Angle λ (°) | Contact Angle α (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screw | 4.75 | 5 | ∞ | 18 | 4.8 | 42.2 |

| Roller | 0.95 | 1 | 2.8 | 6 | 2.9 | 42.2 |

| Nut | 4.75 | 5 | ∞ | 30 | 4.8 | 42.2 |

Using these parameters, I compute the sum of principal curvatures \( \sum \rho \) and the curvature function \( F(\rho) \) for both contact pairs. For the screw-roller contact, \( \sum \rho = 0.3571 + 0.2466 + 0 + 0.1089 = 0.7126 \), and \( F(\rho) = 0.0022 \). For the roller-nut contact, \( \sum \rho = 0.3571 + 0.2466 + 0 + 0.0429 = 0.6466 \), with \( F(\rho) = 0.1534 \). To solve for the ellipticity \( k \) and eccentricity \( e \), I employ numerical methods, specifically Romberg integration for evaluating the elliptic integrals and an iterative approach to satisfy the equation \( F(\rho) = \frac{(1+k^2)L(e) – 2k^2K(e)}{(1-k^2)L(e)} \). This process yields the coefficients \( m_a \) and \( m_b \), allowing me to calculate the elastic deformation \( \delta \) as a function of the normal load \( Q \). The results for varying loads are summarized in Table 2 for the screw-roller contact and Table 3 for the roller-nut contact, illustrating how the contact ellipse dimensions and elastic approach evolve with increasing force.

| Normal Load Q (N) | Semi-major Axis a (mm) | Semi-minor Axis b (mm) | Elastic Deformation δ (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.045 | 0.032 | 0.0008 |

| 20 | 0.057 | 0.040 | 0.0016 |

| 30 | 0.065 | 0.046 | 0.0023 |

| 40 | 0.072 | 0.051 | 0.0030 |

| 50 | 0.078 | 0.055 | 0.0037 |

| Normal Load Q (N) | Semi-major Axis a (mm) | Semi-minor Axis b (mm) | Elastic Deformation δ (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.048 | 0.034 | 0.0009 |

| 20 | 0.060 | 0.043 | 0.0017 |

| 30 | 0.069 | 0.049 | 0.0025 |

| 40 | 0.076 | 0.054 | 0.0032 |

| 50 | 0.082 | 0.058 | 0.0039 |

These tables highlight that for small loads typical in precision applications, the elastic deformations are on the order of micrometers, necessitating compensation in control systems to maintain accuracy. The nonlinear relationship between load and deformation is evident, underscoring the importance of incorporating Hertzian effects in dynamic models of the planetary roller screw assembly.

Beyond elastic deformations, the kinematic transmission relationship governs the axial displacement of the nut relative to the screw’s rotation. For the planetary roller screw assembly, this relationship depends on whether slip occurs at the meshing interfaces. In the ideal no-slip condition, the rollers roll purely between the screw and nut, leading to a geometric derivation based on pitch circle tangencies. Let \( \omega_s \) be the angular velocity of the screw, \( r_s \) and \( r_r \) the pitch radii of the screw and roller, and \( p_s \) and \( p_r \) their respective leads. Considering that the nut is constrained from rotating, the axial displacement \( l \) for a screw rotation angle \( \theta_s \) is given by:

$$ l = \frac{1}{2\pi} \left( p_s \theta_s \pm p_r \frac{\theta_s r_s}{r_r} \right) $$

The sign depends on the handedness of the threads: positive for same-handed threads and negative for opposite-handed ones. In the planetary roller screw assembly I analyze, the screw and roller threads are opposite-handed, so the negative sign applies. Substituting the parameters from Table 1:

$$ l = \frac{1}{2\pi} \left( 4.75 \theta_s – 0.95 \frac{\theta_s \times 9}{3} \right) = 0.302394 \theta_s $$

where \( \theta_s \) is in radians. This equation assumes perfect rolling contact, but in reality, small slip phenomena can occur due to elastic deformations and friction. To account for this, I introduce a slip angle \( \theta_{\text{slide}} \), which represents the portion of screw rotation that does not contribute to kinematic transmission. From empirical data, under rated loads, the slip is approximately 0.5% of the screw rotation, so \( \theta_{\text{slide}} = 0.005 \theta_s \). The effective screw rotation angle becomes \( \theta_s’ = \theta_s – \theta_{\text{slide}} = 0.995 \theta_s \). The modified transmission relationship for the planetary roller screw assembly with slip is then:

$$ l’ = \frac{1}{2\pi} \left( p_s \theta_s’ \pm p_r \frac{\theta_s’ r_s}{r_r} \right) = 0.3008824 \theta_s $$

This slight reduction in axial displacement per unit rotation highlights the need to consider slip in high-precision applications, especially for small angular movements where such effects are proportionally more significant.

To validate the mathematical model and explore the dynamic behavior of the planetary roller screw assembly, I develop a finite element model using a simplified geometry that captures the essential contact interactions. Given the complexity of the full assembly, I focus on a segment containing the engaged threads of the screw, roller, and nut, omitting non-critical cylindrical sections to reduce computational cost. The mesh is generated with tetrahedral elements (C3D4), ensuring at least three layers across each thread surface for accuracy, resulting in a total of 67,944 elements. Material properties are assigned as previously mentioned, and contact interactions are defined using surface-to-surface formulation with a Coulomb friction coefficient of 0.3 for tangential behavior and hard contact for normal direction. The analysis is conducted in two steps: first, a preload force is applied to the nut to establish full contact between threads; second, a torque is applied to the screw to induce rotation and axial motion. Boundary conditions are carefully set: in the first step, axial degrees of freedom are released for the roller and nut, while all other freedoms are constrained; in the second step, rotational freedoms are released for all components. The preload force follows a ramp-up curve to 100 N, and the torque increases linearly to simulate small angular movement over a total time of 0.001 seconds.

The finite element simulation provides insights into the stress distribution and dynamic response of the planetary roller screw assembly. At specific time instances, such as 0.0003136 s and 0.000704 s, the von Mises stress contours reveal that maximum stresses occur at the screw-roller contact points, exceeding the yield strength of the material locally, indicating plastic yielding in these regions. This is attributed to the higher curvature at these interfaces, leading to more concentrated contact pressures. The maximum stress values for each component are summarized in Table 4, demonstrating the load-sharing characteristics and potential failure sites in the planetary roller screw assembly.

| Time (s) | Component | Maximum Stress (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0003136 | Screw | 675.1 |

| Roller (Screw Side) | 1247.0 | |

| Roller (Nut Side) | 761.6 | |

| Nut | 474.4 | |

| 0.000704 | Screw | 984.1 |

| Roller (Screw Side) | 1335.0 | |

| Roller (Nut Side) | 1335.0 | |

| Nut | 424.2 |

The dynamic response curves extracted from the simulation further elucidate the behavior of the planetary roller screw assembly. The angular displacement of the screw shows a linear increase with time under applied torque, while the roller rotates in the opposite direction, and the nut rotates slightly due to constraints but primarily translates axially. The axial displacement curves for the roller and nut exhibit an initial elastic deformation phase during preload, followed by kinematic motion. At 0.0002 s, when the preload force reaches 100 N, the roller’s axial displacement is 0.00164042 mm, which compares favorably with the Hertz theory prediction of 0.0016 mm, yielding a relative error of only 2.5%. This close agreement validates the accuracy of the elastic deformation model for the planetary roller screw assembly. Subsequently, the nut’s axial displacement as a function of screw rotation angle is plotted, and the slope of this curve is found to be 0.300010, nearly identical to the theoretical slip-included value of 0.3008824, with an error of merely 0.29%. This confirms that the derived transmission relationship effectively captures the motion characteristics of the planetary roller screw assembly under small angular movements.

In conclusion, my analysis of the planetary roller screw assembly for small angular movements integrates mathematical modeling and finite element simulation to provide a comprehensive understanding of its dynamics. The Hertz contact theory successfully quantifies elastic deformations at the screw-roller and roller-nut interfaces, revealing that these deformations, though small, are non-negligible in precision applications and should be compensated for in control systems. The transmission relationships, both ideal and slip-adjusted, accurately predict axial displacement, with the slip model showing excellent correlation with simulation results. The finite element analysis not only validates these theoretical findings but also highlights stress concentrations and potential plastic yielding in critical contact zones of the planetary roller screw assembly. These insights are crucial for designing robust and accurate actuation systems in fields like aerospace and robotics, where the planetary roller screw assembly is increasingly deployed. Future work could explore the effects of thermal variations, lubrication, and more complex loading scenarios on the dynamic performance of the planetary roller screw assembly, further enhancing its reliability and efficiency in high-end applications.

Throughout this study, I have emphasized the importance of considering both elastic and kinematic contributions to displacement in the planetary roller screw assembly. The mathematical framework developed here, coupled with numerical simulations, offers a practical tool for engineers to optimize the design and control of systems incorporating the planetary roller screw assembly. By repeatedly addressing key aspects such as contact mechanics, transmission efficiency, and dynamic response, I hope to have underscored the versatility and criticality of the planetary roller screw assembly in modern mechanical engineering. As technology advances towards higher precision and speed, continued research into the nuanced behavior of components like the planetary roller screw assembly will remain essential for pushing the boundaries of performance in motion control systems.