The worm gear drive, as a quintessential component for transmitting motion and power between non-intersecting, perpendicular shafts, is fundamental to the operation of a screw jack mechanism. The performance, reliability, and lifespan of the entire lifting system are intrinsically linked to the dynamic behavior of this worm gear drive. Traditional design methodologies often simplify the complex interaction within the gear mesh, treating the resultant meshing force as a constant value. However, in reality, the meshing stiffness of a worm gear pair undergoes periodic fluctuations during engagement. This time-varying stiffness directly induces corresponding oscillations in the meshing force, leading to vibrations, noise, and accelerated fatigue failure. Therefore, a detailed investigation into the dynamic meshing forces is not merely academic but essential for advancing the design and optimization of screw jack mechanisms. This article presents a comprehensive dynamic simulation study of the worm gear drive within a specific screw jack, leveraging multi-body dynamics to model the complex contact interactions, analyze the characteristics of the meshing force, and investigate the influence of key operational and material parameters.

Introduction to Worm Gear Drives in Mechanical Systems

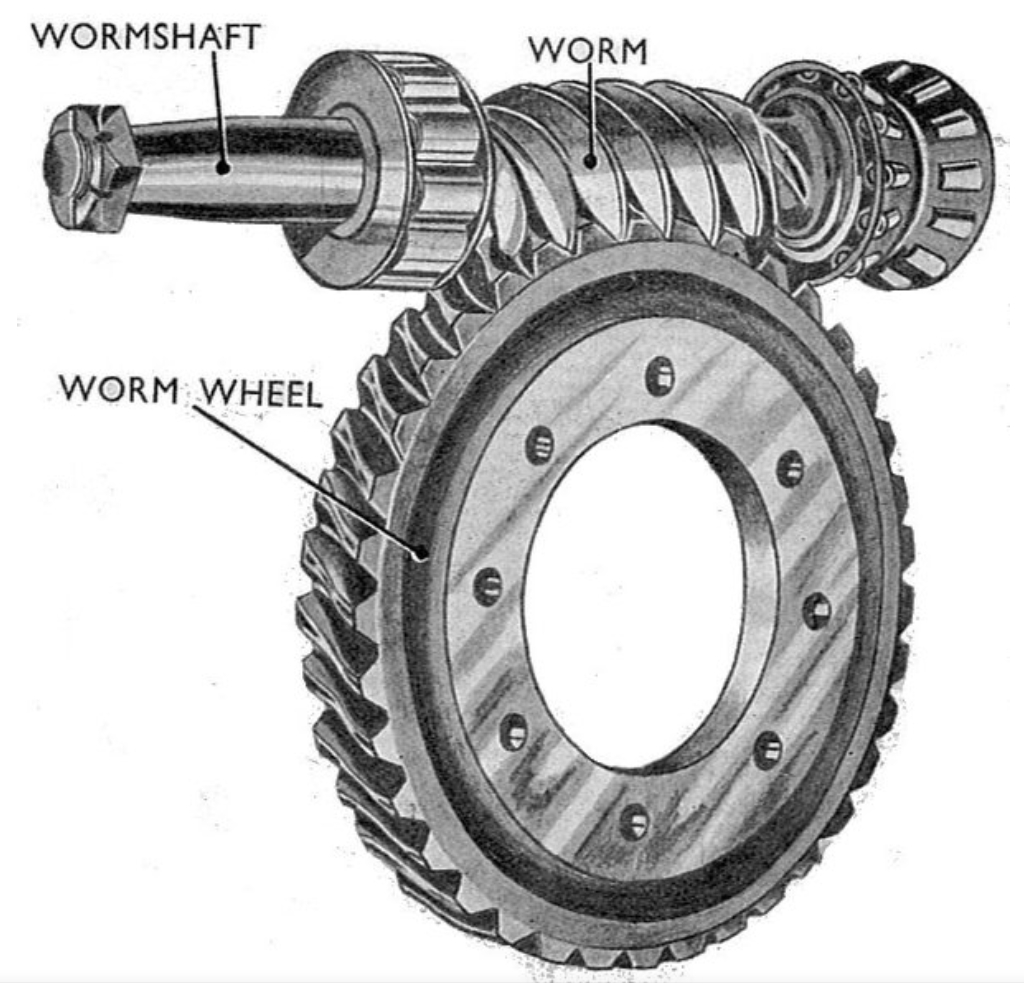

The worm gear drive is renowned for its compact design, high reduction ratios, smooth and quiet operation, and self-locking capability. These attributes make it indispensable in applications like screw jacks, where controlled linear motion is derived from rotary input. The core of a screw jack’s speed reduction unit is typically a worm gear drive. The primary contact between the worm (the driving screw) and the worm wheel (the driven gear) is a sliding/rolling conjugation, which is fundamentally different from the pure rolling contact in parallel axis gears. This sliding action, while enabling high ratios, also generates significant friction and heat. More critically for dynamic analysis, the number of teeth in contact varies cyclically as the worm rotates. This variation causes a periodic change in the overall mesh stiffness of the worm gear drive. Fluctuating stiffness, when coupled with the inertial forces of the components, results in a dynamically changing meshing force. This force transient is the primary excitation source for vibrations within the transmission system. Understanding its magnitude, frequency, and fluctuation pattern is the first step toward mitigating its adverse effects, which include reduced positioning accuracy, increased wear, and premature component failure. Thus, moving beyond static analysis to a dynamic simulation of the meshing process is crucial for modern, high-performance design of worm gear drive systems.

Development of a High-Fidelity Virtual Prototype

The foundation of any accurate dynamic simulation is a precise virtual prototype. The process begins with the accurate geometric modeling of the worm gear drive components.

Geometric Modeling and Assembly

The three-dimensional solid models of the worm and worm wheel were meticulously created using a leading CAD software, adhering to the specified design parameters of the screw jack’s worm gear drive. Key parameters included the number of worm threads, the number of worm wheel teeth, module, pressure angle, and lead angle. The assembly ensured the correct center distance and shaft angle (typically 90 degrees). This fully constrained assembly was then exported in the Parasolid format, a robust geometric kernel, to ensure seamless and lossless data transfer into the multi-body dynamics simulation environment, ADAMS (Automatic Dynamic Analysis of Mechanical Systems).

Upon import, the material properties were assigned to define the inertial characteristics. The worm was modeled as steel (AISI 1045), and the worm wheel as cast iron (Grade HT150). The relevant properties are summarized in Table 1.

| Component | Material | Density (kg/m³) | Young’s Modulus, E (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio, μ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worm | AISI 1045 Steel | 7850 | 210 | 0.269 |

| Worm Wheel | HT150 Cast Iron | 7200 | 130 | 0.250 |

Definition of Kinematic Joints and Contact Forces

To simulate the physical system, appropriate kinematic constraints were applied. A revolute joint was defined between the worm and the ground, allowing the worm to rotate about its central axis. Similarly, a revolute joint was applied to the worm wheel. The most critical aspect of the model is the definition of the contact force between the teeth of the worm and the worm wheel. Unlike a constant ideal gear constraint, a force-based contact model allows for the simulation of impact, separation, and the transmission of force through deformation.

In ADAMS, the Impact function model, based on a spring-damper analogy, was employed to define this contact force for the worm gear drive. The force is computed as a function of the penetration depth between the two contacting geometries. The general form of the Impact function is:

$$ F_{impact} = \begin{cases}

K \cdot \delta^e + C \cdot \dot{\delta} \cdot STEP(\delta, 0, 0, d_{max}, 1), & \text{if } \delta > 0 \\

0, & \text{if } \delta \le 0

\end{cases} $$

Where:

- $F_{impact}$ is the contact force.

- $\delta = q_0 – q$ is the penetration depth ($q_0$ is the initial distance, $q$ is the instantaneous distance).

- $K$ is the contact stiffness coefficient.

- $e$ is the force exponent (typically >1, often derived from Hertzian theory).

- $C$ is the damping coefficient.

- $\dot{\delta}$ is the penetration velocity.

- $STEP$ is a smoothing function that activates the damping force only when penetration exceeds a small threshold $d_{max}$.

Determination of Contact Parameters for the Worm Gear Drive

The accuracy of the dynamic simulation hinges on the correct estimation of the contact parameters, especially the stiffness $K$. For two elastic bodies in contact, the Hertzian contact theory provides a theoretical foundation. For the general case of two cylinders with parallel axes (a good approximation for the localized contact in a worm gear drive), the contact stiffness can be related to the material properties and contact geometry.

The equivalent radius $R$ and equivalent modulus $E^*$ are calculated first:

$$ \frac{1}{R} = \frac{1}{R_1} \pm \frac{1}{R_2} $$

$$ \frac{1}{E^*} = \frac{1 – \mu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1 – \mu_2^2}{E_2} $$

Where $R_1$ and $R_2$ are the radii of curvature at the contact point for the worm and worm wheel teeth, respectively. The sign depends on whether the surfaces are convex or concave. For a worm and worm wheel, this is a complex time-varying value, but an average or representative value based on the pitch cylinder can be used for initial simulation. Using the material properties from Table 1 and estimating the equivalent radius from the design geometry, the nominal contact stiffness $K$ was calculated. The damping coefficient $C$ is typically set to a small percentage (e.g., 0.1% to 1%) of the stiffness to model energy dissipation during impact. The force exponent $e$ for metallic contacts is often taken as 1.5 (Hertzian). The final simulation parameters are listed in Table 2.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stiffness Coefficient | $K$ | 4.39 x 10⁸ N/m | Derived from Hertz theory |

| Force Exponent | $e$ | 1.5 | Hertzian contact exponent |

| Damping Coefficient | $C$ | 4.39 x 10⁵ N·s/m | ~0.1% of stiffness |

| Penetration Depth | $d_{max}$ | 1.0 x 10⁻⁴ m | Activation threshold for damping |

| Static Friction Coefficient | $\mu_s$ | 0.10 | Coulomb friction model |

| Dynamic Friction Coefficient | $\mu_d$ | 0.05 | Coulomb friction model |

The final virtual prototype of the worm gear drive, with all joints, contacts, and forces defined, is a solvable dynamic system ready for analysis.

Dynamic Simulation and Meshing Force Analysis

With the virtual prototype established, a dynamic simulation was performed. A constant angular velocity drive was applied to the revolute joint of the worm. The chosen input speed for the baseline simulation was 1330 revolutions per minute (RPM). The simulation accounted for the dynamic effects of inertia and the nonlinear contact force in the worm gear drive.

Kinematic Validation

Prior to analyzing forces, it is essential to validate the basic kinematics of the model. The theoretical output speed of the worm wheel ($\omega_{wheel,theo}$) is determined by the gear ratio $i$:

$$ \omega_{wheel,theo} = \frac{\omega_{worm,input}}{i} $$

For an input of 1330 RPM (139.3 rad/s) and a gear ratio $i = 24$, the theoretical output speed is approximately 55.4 RPM (5.80 rad/s or 332.5 deg/s). The simulation output for the worm wheel angular velocity is shown in Figure 1 (conceptual). After the initial transient, the simulated speed oscillates around a mean value of approximately 328.8 deg/s. The relative error between simulation and theory is about 1.1%, which falls within an acceptable range considering numerical solvers, contact modeling approximations, and the absence of considerations for friction losses in the theoretical calculation. This close agreement validates the fundamental kinematic accuracy of the worm gear drive virtual prototype.

Characteristics of the Meshing Force

The primary output of interest is the meshing force between the worm and worm wheel. Figure 2 (conceptual) depicts the simulated meshing force over time. The analysis reveals several critical characteristics inherent to the dynamics of a worm gear drive:

- Start-up Impact: At the instant of startup (t=0), a very high impulse force is observed, peaking at over 24,000 N. This is due to the sudden application of motion to the inertias of the system when the gear teeth are not perfectly aligned, causing a high-rate initial penetration $\delta$.

- Steady-State Fluctuation: After the initial transient, the system settles into a steady-state meshing condition. The force does not stabilize to a constant value. Instead, it exhibits clear, periodic fluctuations around a mean value of approximately 414 N. This mean force is related to the transmitted torque required to drive the load on the worm wheel.

- Periodicity and Source of Fluctuation: The fluctuation is periodic, with a frequency linked to the tooth meshing frequency. The root cause is the cyclic variation in the mesh stiffness of the worm gear drive. As different pairs of teeth come into and out of contact, and as the contact point moves along the tooth profile, the effective stiffness of the gear pair changes. According to the basic equation of motion for a simplified one-degree-of-freedom gear model:

$$ I \ddot{\theta} + C \dot{\theta} + K(t) \theta = T(t) $$

where $K(t)$ is the time-varying mesh stiffness. Even with a constant input torque $T(t)$, the variation in $K(t)$ directly causes a variation in the dynamic displacement $\theta$ and consequently in the dynamic force $F_{mesh} = K(t) \cdot \theta$. - Implications for Design: This periodic fluctuation of the meshing force is a fundamental source of vibration and noise in a worm gear drive. More importantly, it subjects the gear teeth to cyclic stress variations, which is the primary driver of fatigue failure (pitting, bending fatigue). Therefore, for enhancing the durability, reliability, and operational smoothness of a screw jack mechanism, design measures aimed at reducing the amplitude of the meshing force fluctuation are paramount. This could involve optimizing tooth geometry for more constant mesh stiffness, improving manufacturing accuracy to reduce transmission error, or using materials with better damping characteristics.

Parametric Study: Influence of Key Factors on Meshing Force

To gain deeper insight, a parametric study was conducted to evaluate how the meshing force in the worm gear drive responds to changes in material stiffness and operational speed.

Effect of Contact Stiffness Coefficient (K)

The contact stiffness $K$ is a function of material properties (Young’s Modulus) and geometry. Simulations were run with different stiffness values while keeping the input speed constant at 1330 RPM. The results are summarized in Table 3 and illustrated conceptually in Figure 3.

| Stiffness, K (N/m) | Mean Meshing Force (N) | Peak-to-Peak Fluctuation (Approx. N) | Maximum Force (N) | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.00 x 10⁸ | 221 | ~10,940 | 10,945 | Lower mean force, high relative fluctuation. |

| 4.39 x 10⁸ (Baseline) | 414 | ~21,850 | 21,889 | Baseline performance. |

| 6.00 x 10⁸ | 550 | ~32,830 | 32,834 | Higher mean force, severe fluctuation. |

The findings are clear:

- Direct Correlation: The magnitude of the mean meshing force increases almost proportionally with the contact stiffness. A stiffer worm gear drive transmits force more directly with less compliance.

- Amplified Fluctuations: Critically, the amplitude of the force fluctuations increases dramatically with stiffness. Higher stiffness reduces the system’s damping ratio and makes it more sensitive to the periodic excitation from the variable mesh stiffness, leading to more severe dynamic loads. This suggests that while a stiff gear is good for positional accuracy, excessive stiffness can be detrimental from a dynamic load and fatigue perspective.

The relationship can be conceptualized from the simplified dynamic equation. For a given kinematic excitation $\theta_{error}$ (due to variable stiffness), the dynamic force is roughly proportional to stiffness: $F_{dyn} \propto K \cdot \theta_{error}$.

Effect of Input Rotational Speed (ω)

The input speed of the worm is a major operational variable. Simulations were run at different speeds while maintaining the baseline contact stiffness. The results are summarized in Table 4.

| Input Speed, n (RPM) | Mean Meshing Force (N) | Peak-to-Peak Fluctuation (Approx. N) | Maximum Force (N) | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 324 | ~18,070 | 18,071 | Lower dynamic forces. |

| 1330 (Baseline) | 414 | ~21,850 | 21,889 | Baseline performance. |

| 1500 | 498 | ~27,090 | 27,090 | |

| 2000 | 685 | ~36,110 | 36,109 | Significantly higher and more violent fluctuations. |

The analysis reveals a significant trend:

- Force Increase with Speed: Both the mean meshing force and the amplitude of its fluctuations increase substantially with the input speed of the worm gear drive.

- Dynamic Inertia Effects: At higher speeds, inertial forces ($I \ddot{\theta}$) become more dominant. The system has less time to damp out the perturbations caused by the varying mesh stiffness within each meshing cycle. This leads to larger dynamic overshoots and greater force oscillations.

- Resonance Risk: As speed increases, the tooth meshing frequency (and its harmonics) also increases. There is a heightened risk of exciting structural resonances within the worm gear drive or the broader screw jack assembly when these frequencies align with natural frequencies, which would lead to catastrophic amplification of forces and vibrations.

The governing equation shows that the inertial term $I \ddot{\theta}$ is speed-dependent. For a periodic excitation at frequency $\omega_{mesh}$, the dynamic response amplitude can be related to frequency ratio. As $\omega_{mesh}$ increases, it can approach resonant conditions, leading to higher dynamic forces.

Conclusions and Engineering Implications

This detailed dynamic simulation study of a screw jack worm gear drive provides valuable insights that transcend traditional static design approaches. The key conclusion is that the meshing force is not a static load but a dynamically fluctuating one, with its periodic variation being an inherent characteristic caused by the time-varying mesh stiffness of the worm gear drive. This fluctuation is the principal source of vibration, noise, and fatigue-driven failure in these mechanisms.

The parametric studies quantify significant influences:

- Design Trade-off with Stiffness: While a high stiffness is generally desirable for precision, it linearly amplifies the dynamic force fluctuations. Optimal design of a worm gear drive must balance static stiffness with dynamic performance, potentially incorporating targeted compliance or damping.

- Operational Limits with Speed: Operating the worm gear drive at higher input speeds linearly increases the mean load but can super-linearly increase the dynamic load amplitude due to inertial effects. Defining a safe operational speed envelope is crucial to avoid excessive dynamic loads and potential resonance.

The primary engineering directive arising from this analysis is that efforts to improve the lifespan and accuracy of screw jack worm gear drives should focus on minimizing the amplitude of the meshing force fluctuation. This can be achieved through:

- Gear Geometry Optimization: Designing tooth profiles and lead modifications to achieve a more constant mesh stiffness throughout the engagement cycle.

- Precision Manufacturing: Reducing gear errors (pitch, profile, runout) that act as additional excitation sources beyond the inherent stiffness variation.

- Material Selection: Utilizing materials or surface treatments with favorable damping properties to dissipate vibrational energy.

- System Design: Ensuring the supporting bearings and housing have adequate stiffness and damping to suppress transmitted vibrations.

In summary, this simulation framework and the results presented establish a foundation for the dynamic analysis and model-based optimization of worm gear drives. By acknowledging and quantitatively analyzing the dynamic meshing forces, engineers can develop more robust, reliable, and quiet screw jack mechanisms and other power transmission systems reliant on worm gear drive technology.