In mechanical transmission systems, the lubrication performance of screw gear drives is critical for ensuring efficiency, durability, and reliability. Among various types of screw gear drives, the inclined double-roller enveloping hourglass screw gear drive represents an innovative design that replaces traditional worm wheel teeth with rollers, transforming sliding friction into rolling friction. This configuration not only reduces wear but also enhances load-carrying capacity and transmission precision. However, the elastohydrodynamic lubrication (EHL) characteristics of such screw gear drives are complex, especially when considering surface roughness, which is inherent in real-world manufacturing processes. Absolutely smooth surfaces do not exist; when the surface roughness is much smaller than the lubricant film thickness, the surfaces can be assumed smooth. But in EHL, the film thickness is often on the order of micrometers or even sub-micrometers, comparable to the surface roughness from grinding processes in screw gear drives. Therefore, ignoring roughness can lead to inaccurate lubrication assessments and potential failure risks such as scuffing or pitting. This article aims to investigate the EHL properties of the inclined double-roller enveloping hourglass screw gear drive, incorporating surface roughness effects, using numerical methods based on Newtonian fluid EHL theory. The analysis focuses on the influences of rough peaks and grooves on oil film pressure and thickness, examines the lubrication behavior at different meshing points, and evaluates the impact of key design parameters like roller radius, orifice coefficient, and offset distance. The goal is to provide theoretical insights for optimizing the lubrication performance of this advanced screw gear drive, ensuring its application in high-performance transmission systems.

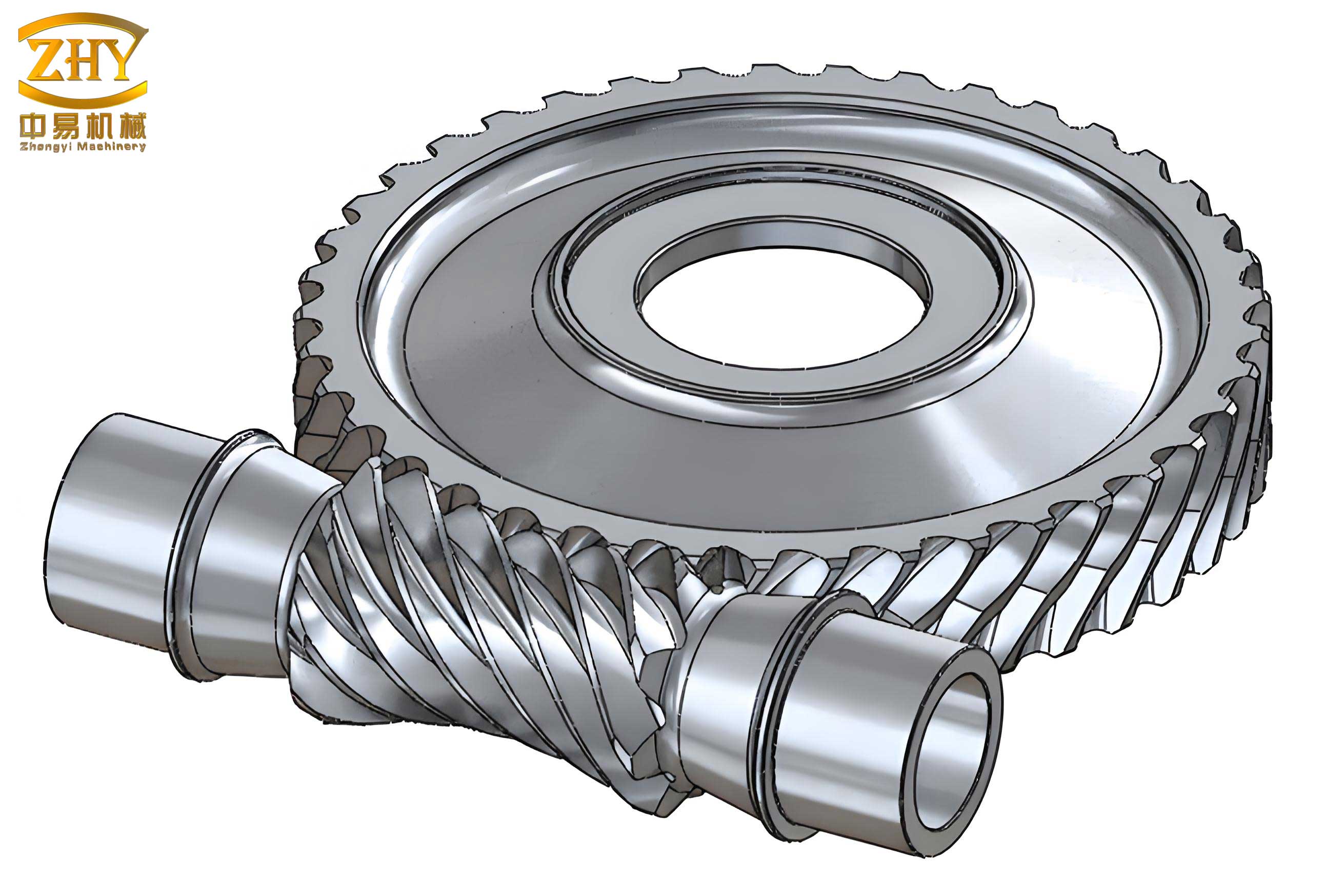

The inclined double-roller enveloping hourglass screw gear drive, as shown in the figure, consists of a worm and a worm wheel. The worm wheel is composed of a fixed wheel and a movable wheel, with rollers uniformly distributed along the circumference. The roller axes are inclined at an angle γ relative to the radial direction of the worm wheel, known as the roller inclination angle. This inclination allows the rollers to rotate about their own axes, converting sliding friction into rolling friction. The hourglass worm is generated by enveloping the outer cylindrical surface of a bearing, resulting in a complex spatial contact line during meshing. For each meshing tooth pair, there is only one contact line, and the drive exhibits instantaneous multi-tooth engagement. The equivalent curvature radius, entrainment velocity, and load per unit length vary along the meshing path from entry to exit, influencing the EHL conditions significantly. The equivalent curvature radius R is given by the inverse of the induced normal curvature:

$$ R = \frac{1}{k_\sigma} $$

where $k_\sigma$ is the induced normal curvature, which can be derived from meshing theory. The entrainment velocity $v_{jx}$ is calculated as the average of the worm and worm wheel velocities along the contact normal direction:

$$ v_{jx} = \frac{v_w + v_g}{2} $$

Here, $v_w$ and $v_g$ are the velocities of the worm and worm wheel at the meshing point, respectively. The load per unit length $w_i$ for each tooth pair at the meshing point is expressed as:

$$ w_i = \frac{F_{ni}}{L} = \frac{F_{t1}}{L \cos \alpha_n \cos \beta} = \frac{2 K_i T_1}{L d_1 \cos \alpha_n \cos \beta} $$

where $i = 1, 2, 3, 4$ denotes the tooth pair index, $K_i$ is the load distribution factor among teeth, $F_{ni}$ is the normal load, $L$ is the contact line length, $F_{t1}$ is the circumferential force, $\alpha_n$ is the pressure angle, $\beta$ is the helix angle, $T_1$ is the input torque, and $d_1$ is the pitch diameter of the worm. The variations of $R$, $v_{jx}$, and $w$ from meshing-in to meshing-out are crucial for understanding the EHL behavior. Typically, the equivalent curvature radius increases gradually, the entrainment velocity decreases first and then increases, and the load per unit length increases first and then decreases, with the minimum entrainment velocity and maximum load occurring near the throat of the worm. This screw gear drive design offers advantages in reducing friction and improving efficiency, but its lubrication mechanics require detailed analysis to prevent failures.

To analyze the EHL of this screw gear drive, a simplified line contact model is employed, where the contact between the worm tooth surface and the roller surface is approximated as an equivalent cylinder against a plane. This simplification is valid under the assumption of pure rolling contact and allows for the application of classic EHL theories. The mathematical model for line contact EHL includes the Reynolds equation, film thickness equation, viscosity-pressure relation, density-pressure relation, and load balance equation. Considering surface roughness, the film thickness equation incorporates a roughness function to account for rough peaks and grooves. The dimensionless forms of these equations are used for numerical solution, with normalization parameters defined as follows:

$$ X = \frac{x}{b}, \quad H = \frac{h}{R}, \quad W = \frac{w}{E’ R}, \quad U = \frac{\eta_0 v_{jx}}{E’ R}, \quad P = \frac{p}{p_H}, \quad \eta^* = \frac{\eta}{\eta_0}, \quad \rho^* = \frac{\rho}{\rho_0} $$

where $E’$ is the composite elastic modulus, $h$ is the film thickness, $w$ is the load per unit length, $\eta_0$ is the initial viscosity, $x$ is the coordinate along the flow direction, $b$ is the Hertzian contact half-width, $p$ is the film pressure, $p_H$ is the maximum Hertzian contact pressure, and $\rho_0$ is the initial density. The dimensionless Reynolds equation for steady-state isothermal conditions is:

$$ \frac{d}{dX} \left( \epsilon \frac{dP}{dX} \right) = \frac{d(\rho^* H)}{dX} $$

with $\epsilon = \frac{\rho^* H^3}{\eta^* \lambda}$ and $\lambda = \frac{12 \eta_0 U R^2}{p_H b^2}$. The boundary conditions are $P(X_{in}) = 0$ at the inlet and $P(X_{out}) = \frac{dP(X_{out})}{dX_{out}} = 0$ at the outlet. The film thickness equation, including surface roughness, is:

$$ H(X) = H_0 + \frac{X^2}{2} – \frac{1}{\pi} \int_{X_{in}}^{X_{out}} \ln |X – X’| P(X’) dX’ \pm S(X) $$

where $H_0$ is the dimensionless rigid central film thickness, and $S(X)$ is the dimensionless surface roughness function. For a single rough peak or groove, a simplified model is used:

$$ S(X) = \delta (|X| – 1)^2 $$

Here, $\delta$ represents the amplitude of the roughness. The positive sign corresponds to a rough peak, and the negative sign to a rough groove. The viscosity-pressure relationship follows the Barus equation or similar empirical forms, such as:

$$ \eta^* = \exp \left\{ (\ln \eta_0 + 9.67) \left[ (1 + 5.1 \times 10^{-9} p)^z – 1 \right] \right\} $$

with $z = \alpha / [5.1 \times 10^{-9} (\ln \eta_0 + 9.667)]$, where $\alpha$ is the pressure-viscosity coefficient. The density-pressure relation is:

$$ \rho^* = 1 + \frac{0.6 \times 10^{-9} p}{1 + 1.7 \times 10^{-9} p} $$

The load balance equation in dimensionless form is:

$$ \int_{X_{in}}^{X_{out}} P(X) dX = \frac{\pi}{2} $$

These equations form a nonlinear system that requires numerical methods for solution. The Newton-Raphson method and Newton iteration are applied to discretize the equations using finite differences. The discretized Reynolds equation is:

$$ f_i = H_i^3 \left( \frac{dP}{dX} \right)_i – A \eta_i \left( H_i – \frac{\rho_{out} H_{out}}{\rho_i} \right) = 0 $$

where $A = \frac{3\pi^2 U}{4W^2}$ is a dimensionless coefficient, and $\rho_{out} H_{out}$ is the product of density and film thickness at the outlet. The film thickness discretization is:

$$ H_i = H_0 + \frac{x_i^2}{2R} + \sum_{j=1}^n K_{ij} P_j \pm \delta (|x_i| – 1)^2 $$

with $K_{ij}$ as the deformation influence coefficients. The load balance discretization is:

$$ \sum_{i=1}^n P_i \Delta X = \frac{\pi}{2} $$

The numerical solution process involves iterating until convergence for pressure distribution, film thickness, and outlet boundary. This approach allows for analyzing the EHL characteristics under various roughness conditions and design parameters for the screw gear drive.

The numerical analysis is conducted with specific parameters for the inclined double-roller enveloping hourglass screw gear drive. The input power is 5 kW, input speed is 1450 rpm, worm and worm wheel material properties are Poisson’s ratio $\mu_1 = \mu_2 = 0.3$ and Young’s modulus $E_1 = E_2 = 210$ GPa. The drive has a right-hand worm with $Z_1 = 1$ thread, $Z_2 = 25$ rollers, center distance $A = 125$ mm, roller radius $R_z = 6.5$ mm, offset distance $c_2 = 7$ mm, orifice coefficient $k = 0.4$, pressure angle $\alpha = 1^\circ$, and roller inclination angle $\gamma = 6^\circ$. The dimensionless computational domain is set to $X = [-3, 1.5]$. The effects of surface roughness amplitude $\delta$ on oil film pressure and thickness are examined for both rough peaks and rough grooves. The results show that roughness significantly influences the EHL behavior, with implications for the lubrication performance of the screw gear drive.

Table 1 summarizes the key parameters used in the EHL analysis of the screw gear drive.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input power | $P$ | 5 | kW |

| Input speed | $n_1$ | 1450 | rpm |

| Number of worm threads | $Z_1$ | 1 | – |

| Number of rollers | $Z_2$ | 25 | – |

| Center distance | $A$ | 125 | mm |

| Roller radius | $R_z$ | 6.5 | mm |

| Offset distance | $c_2$ | 7 | mm |

| Orifice coefficient | $k$ | 0.4 | – |

| Pressure angle | $\alpha_n$ | 1 | degree |

| Roller inclination angle | $\gamma$ | 6 | degree |

| Composite elastic modulus | $E’$ | 210 | GPa |

| Initial viscosity | $\eta_0$ | 0.08 | Pa·s |

| Pressure-viscosity coefficient | $\alpha$ | 2.2e-8 | Pa$^{-1}$ |

For a roughness amplitude of $\delta = 0.1 \mu m$, the oil film pressure and thickness distributions at four different meshing points (from the first tooth engaging to the fourth) are analyzed. The meshing points correspond to different worm wheel rotation angles $\phi_2$. The results indicate that from meshing-in to meshing-out, the smooth solution shows that the secondary pressure peak of the EHL oil film first increases and then decreases, while the film thickness first decreases and then increases. In the rough peak case, the oil film pressure exhibits a凸起 (bulge) in the roughness region, forming a local high pressure that can partially press the peak into the surface, reducing the risk of film penetration. In contrast, for rough grooves, the pressure shows a凹陷 (dent), leading to dual pressure peaks in the smooth regions adjacent to the groove, which may increase the risk of film penetration and lubrication failure. At the moment when the third tooth begins to mesh, the oil film pressure peak is maximum, and the film thickness is minimum, identifying this as the most critical region for lubrication in the screw gear drive. The roughness amplitude $\delta$ has a pronounced effect: larger $\delta$ values worsen lubrication, with rough peaks causing earlier film necking and rough grooves delaying it. Table 2 presents the film thickness and pressure characteristics at different meshing points for smooth, rough peak, and rough groove conditions.

| Meshing Point | Condition | Min Film Thickness (μm) | Max Pressure (GPa) | Secondary Pressure Peak (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st tooth engagement | Smooth | 0.85 | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| Rough Peak ($\delta=0.1 \mu m$) | 0.82 | 1.25 | 0.85 | |

| Rough Groove ($\delta=0.1 \mu m$) | 0.88 | 1.15 | 0.75 | |

| 2nd tooth engagement | Smooth | 0.78 | 1.3 | 0.9 |

| Rough Peak | 0.75 | 1.35 | 0.95 | |

| Rough Groove | 0.81 | 1.25 | 0.85 | |

| 3rd tooth engagement | Smooth | 0.72 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| Rough Peak | 0.68 | 1.45 | 1.05 | |

| Rough Groove | 0.76 | 1.35 | 0.95 | |

| 4th tooth engagement | Smooth | 0.80 | 1.25 | 0.85 |

| Rough Peak | 0.77 | 1.30 | 0.90 | |

| Rough Groove | 0.83 | 1.20 | 0.80 |

The influence of design parameters on EHL characteristics is also investigated. The roller radius $R_z$, offset distance $c_2$, and orifice coefficient $k$ are varied while keeping other parameters constant. The results show that increasing $R_z$ leads to a decrease in film thickness and an increase in secondary pressure peak for both rough peaks and grooves, with the peak shifting toward the outlet. This suggests that larger roller radii may adversely affect lubrication in the screw gear drive. Similarly, increasing $c_2$ reduces film thickness and alters pressure distribution, indicating that excessive offset distance is detrimental. For the orifice coefficient $k$, a larger $k$ (e.g., from 0.3 to 0.5) results in reduced film thickness and modified pressure peaks, implying that a very small $k$ should be avoided to maintain good lubrication. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing design parameters for enhancing the EHL performance of the screw gear drive. Table 3 summarizes the trends for different design parameter changes.

| Design Parameter | Change | Effect on Film Thickness | Effect on Pressure Peak | Recommendation for Screw Gear Drive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roller radius ($R_z$) | Increase | Decreases | Increases and shifts outlet-ward | Avoid too large $R_z$ |

| Offset distance ($c_2$) | Increase | Decreases | Increases for rough grooves, decreases for rough peaks | Avoid too large $c_2$ |

| Orifice coefficient ($k$) | Increase | Decreases | Varies: increases for rough peaks, decreases for rough grooves | Avoid too small $k$ |

The numerical solution process involves several steps to ensure accuracy. The dimensionless equations are discretized over a grid with 501 nodes, and convergence criteria are set for pressure and film thickness residuals below $10^{-6}$. The initial guess for pressure is the Hertzian distribution, and for film thickness, the parabolic shape. The Newton-Raphson method updates the pressure and film thickness iteratively until the load balance equation is satisfied. The roughness function $S(X)$ is added to the film thickness equation during iterations, allowing for the analysis of both peak and groove effects. The computational domain is set from $X = -3$ to $X = 1.5$ to capture the inlet and outlet regions adequately. The lubricant properties are based on a typical mineral oil with $\eta_0 = 0.08$ Pa·s and $\alpha = 2.2 \times 10^{-8}$ Pa$^{-1}$. The composite elastic modulus $E’$ is calculated from the worm and wheel materials:

$$ E’ = \frac{2}{\frac{1 – \mu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1 – \mu_2^2}{E_2}} $$

For the given parameters, $E’ \approx 210$ GPa. The Hertzian contact half-width $b$ and maximum pressure $p_H$ are derived from the load per unit length $w$ and equivalent curvature radius $R$:

$$ b = \sqrt{\frac{8 w R}{\pi E’}}, \quad p_H = \frac{2 w}{\pi b} $$

These values are used in the dimensionless analysis. The entrainment velocity $v_{jx}$ is computed at each meshing point based on the kinematic relations of the screw gear drive. The load distribution factor $K_i$ is assumed based on engagement conditions, with typical values ranging from 0.2 to 0.4 for multi-tooth meshing in such screw gear drives. The contact line length $L$ is estimated from the geometry of the roller and worm interaction. These inputs feed into the EHL model to generate the pressure and thickness profiles.

Furthermore, the impact of surface roughness on the screw gear drive’s lubrication is analyzed in detail. For rough peaks, the local high pressure in the peak region can cause elastic deformation that flattens the peak, effectively reducing its height and mitigating film penetration. This phenomenon is described by the film thickness equation with the positive $S(X)$ term. However, if the peak is too sharp or large, it may still penetrate the film, leading to metal-to-metal contact and increased wear. For rough grooves, the reduced pressure in the groove region can cause lubricant cavitation or starvation, while the adjacent smooth areas experience higher pressure peaks, potentially causing stress concentrations and fatigue. The dual pressure peaks observed in rough groove cases are a result of the pressure redistribution to maintain load balance. Mathematically, this can be expressed as a perturbation to the smooth solution. The roughness amplitude $\delta$ directly affects the magnitude of these perturbations. For instance, the pressure perturbation $\Delta P$ due to roughness can be approximated as:

$$ \Delta P \approx \frac{\partial P}{\partial H} \Delta H $$

where $\Delta H = \pm S(X)$. Since $\frac{\partial P}{\partial H}$ is negative in the contact zone, a positive $\Delta H$ (rough peak) leads to a negative $\Delta P$ (pressure decrease) locally, but the overall pressure peak may increase due to compensation in other regions. Conversely, a negative $\Delta H$ (rough groove) leads to a positive $\Delta P$ locally, but the global effect is complex. These interactions underline the importance of considering roughness in EHL analyses for screw gear drives.

In addition to single rough peaks or grooves, real surfaces have random roughness profiles. However, the single-peak model serves as a foundational case to understand the mechanisms. Future work could extend to fractal or measured roughness patterns. The screw gear drive’s performance is also influenced by thermal effects, non-Newtonian lubricant behavior, and dynamic loads, which are beyond the scope of this analysis but are essential for comprehensive design. Nevertheless, the isothermal Newtonian model provides valuable insights into the basic EHL characteristics.

The conclusion drawn from this study emphasizes that surface roughness has adverse effects on the lubrication of the inclined double-roller enveloping hourglass screw gear drive. Larger roughness amplitudes worsen lubrication, making the drive more prone to failures. The third tooth engagement moment is identified as the most critical region, where film thickness is minimal and pressure is maximal. To maintain good lubrication, design parameters should be optimized: roller radius and offset distance should not be too large, and the orifice coefficient should not be too small. Improving manufacturing precision to reduce surface roughness is recommended to enhance the EHL load-carrying capacity of the screw gear drive. These findings contribute to the theoretical foundation for designing and operating high-performance screw gear drives in applications such as robotics, automotive transmissions, and industrial machinery.

To further elaborate, the mathematical model can be extended to include transient effects, as the meshing process involves time-varying conditions. The dimensionless Reynolds equation with time term is:

$$ \frac{d}{dX} \left( \epsilon \frac{dP}{dX} \right) = \frac{d(\rho^* H)}{dX} + \frac{d(\rho^* H)}{dT} $$

where $T$ is dimensionless time. For the screw gear drive, the meshing cycle can be discretized into time steps, and the EHL equations solved at each step to capture dynamic behavior. However, for simplicity, the steady-state assumption is often used in initial analyses. The numerical methods described here are robust and can be adapted for transient simulations. The use of advanced solvers like multigrid methods could improve computational efficiency for large-scale analyses of screw gear drives.

In summary, this article presents a comprehensive EHL analysis of the inclined double-roller enveloping hourglass screw gear drive, considering surface roughness. The methodology combines theoretical modeling with numerical solutions, yielding insights into pressure and film thickness distributions under various conditions. The results underscore the significance of roughness and design parameters in determining lubrication performance. By applying these findings, engineers can better design and maintain screw gear drives for optimal operation and longevity. The screw gear drive, with its unique roller-based design, offers promising advantages, and understanding its EHL behavior is key to unlocking its full potential in modern transmission systems.

Finally, it is worth noting that the screw gear drive technology continues to evolve, with ongoing research focusing on materials, coatings, and lubrication additives to further improve performance. The integration of EHL analysis into the design process enables predictive maintenance and failure prevention, reducing downtime and costs. As industries demand higher efficiency and reliability, advanced screw gear drives will play an increasingly important role, and studies like this provide the necessary groundwork for innovation.