In the manufacturing industry, particularly in gear production, heat treatment processes play a critical role in determining the mechanical properties and service life of components. From my perspective as an engineer specializing in materials science, I have observed that while carburizing offers superior comprehensive mechanical properties, it is often energy-intensive and complex. In contrast, induction hardening presents a more energy-efficient alternative with shorter process cycles and lower distortion. However, the adoption of induction hardening is limited by strength-related concerns and potential heat treatment defects. This article delves into the analysis of gear strength to explore how energy savings can be achieved through optimized heat treatment processes, with a focus on mitigating heat treatment defects such as transition zone weaknesses, soft bands, and cracking tendencies.

The drive for energy efficiency in heat treatment is not merely an economic imperative but also an environmental one. With the global gear industry witnessing substantial growth—for instance, production value reaching significant figures—the cumulative energy consumption and associated costs, including grinding expenses post-carburizing, are staggering. Therefore, expanding the application of energy-saving processes like induction hardening holds immense significance. Yet, the selection of heat treatment工艺 is primarily governed by strength requirements. Thus, to broaden the use of induction hardening, it is essential to understand the physical metallurgical factors influencing gear strength and how they interplay with energy consumption.

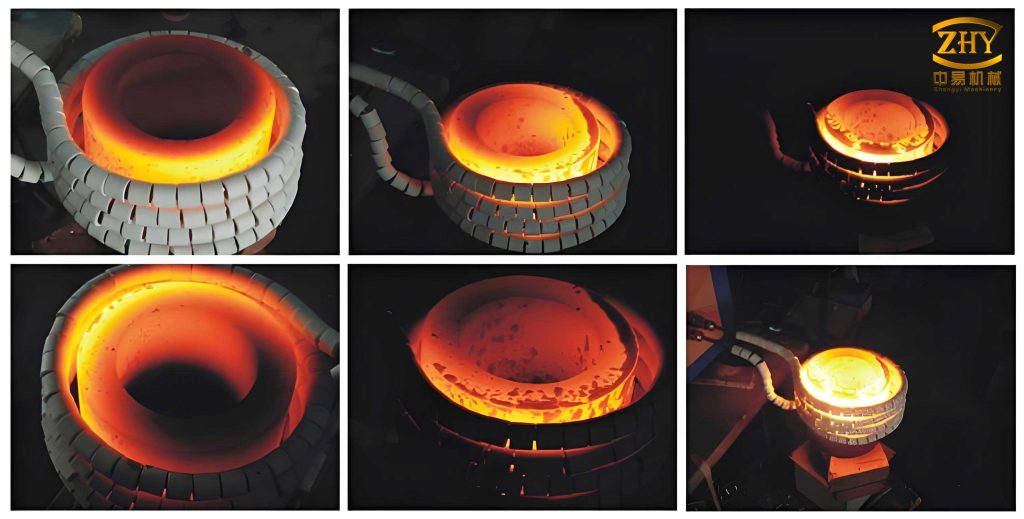

Induction Hardening of Gears: Strength Issues and Energy Efficiency

Induction hardening is renowned for its rapid processing, minimal deformation, and lower energy input compared to carburizing. However, from a strength standpoint, several inherent challenges must be addressed to ensure its viability for high-performance gears. These challenges often manifest as heat treatment defects that can compromise gear integrity.

One major issue is the weak transition zone between the hardened layer and the core material. During induction hardening, the rapid heating and quenching can lead to residual stress distributions that are unfavorable. For example, in components like cold work rolls, the transition zone exhibits high tensile stresses, as illustrated in stress distribution curves. This can be represented mathematically by the residual stress profile, where the stress $\sigma(x)$ varies with depth $x$ from the surface. The tensile stress peak in the transition zone, often denoted as $\sigma_{max}$, can be estimated using formulas derived from thermal and phase transformation models. For instance, the stress might follow a relation like:

$$\sigma(x) = \sigma_0 + A e^{-kx} \cos(\omega x)$$

where $\sigma_0$ is the base stress, and $A$, $k$, and $\omega$ are constants dependent on material and process parameters. This tensile stress concentration acts as a potential site for fatigue crack initiation, a common heat treatment defect that reduces bending and contact fatigue strength.

Another heat treatment defect in induction hardening is the formation of a soft band due to overtempering. Given the nature of induction heating, the region between the hardened layer and the tempered core can experience excessive heat exposure, leading to a drop in hardness. This soft band, with hardness values potentially falling below 40 HRC, creates a weak link in the gear tooth. The hardness distribution $H(x)$ can be modeled as:

$$H(x) = H_{surface} – \Delta H \cdot \left(1 – e^{-(x-d)/\lambda}\right)$$

where $H_{surface}$ is the surface hardness, $\Delta H$ is the hardness decrement, $d$ is the depth of the hardened layer, and $\lambda$ is a decay constant. This defect necessitates careful control of heating parameters to avoid compromising gear strength.

Furthermore, single-tooth hardening along the tooth groove, while desirable for optimizing contact and bending fatigue strength, is prone to quenching cracks. Computational simulations and X-ray stress measurements reveal that tensile residual stresses develop at the tooth root, increasing the risk of cracking. This heat treatment defect is exacerbated when using medium-carbon alloy steels, where hardness typically ranges from 45 to 55 HRC. To achieve higher hardness levels, increasing the carbon content is necessary, but this elevates the susceptibility to quenching cracks. Thus, balancing carbon content and process conditions is crucial to prevent such defects.

To overcome these heat treatment defects and enhance strength, several process improvements have been developed. Among them, contour hardening using a “single-shot” method or dual-frequency induction heating is particularly effective. Dual-frequency heating involves initial low-frequency preheating followed by high-frequency finishing, which promotes a more uniform hardened layer along the tooth profile. This approach mitigates tensile stresses at the tooth root and reduces cracking tendencies. The energy input in dual-frequency hardening can be optimized by adjusting frequencies and power levels. For example, the total energy $E$ required might be expressed as:

$$E = P_{LF} \cdot t_{LF} + P_{HF} \cdot t_{HF}$$

where $P_{LF}$ and $P_{HF}$ are the power outputs at low and high frequencies, respectively, and $t_{LF}$ and $t_{HF}$ are the corresponding heating times. This method allows for better control over the hardened depth $d_h$, which is critical for fatigue performance. Table 1 compares the process steps and economic aspects of induction hardening versus carburizing, highlighting the energy-saving potential of induction methods.

| Aspect | Carburizing (Press Quenching) | Carburizing (Free Quenching) | Induction Hardening (Dual-Frequency) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Steps | 18 steps: rough machining, degreasing, shielding, copper plating, etc. | 14 steps: similar to left but with fewer steps | 9 steps: rough machining, pre-heat treatment, degreasing, tempering, final machining, induction hardening, tempering, unloading, inspection |

| Energy and Cost | Higher energy consumption due to long cycle times; grinding adds cost | Moderate energy use; grinding required | Lower energy input; no grinding needed in many cases |

| Time Efficiency | Several days for complete process | Similar to left | Minutes for hardening cycle |

The effectiveness of dual-frequency hardening is evident in hardened layer depth and surface hardness. For instance, as shown in Table 2, dual-frequency quenching achieves a more controlled depth compared to single-frequency methods, resembling carburized layers but with shorter process times. This directly translates to energy savings while maintaining strength.

| Test Location | Dual-Frequency Hardening | Single-Frequency Hardening | Carburizing and Tempering |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tooth Root | Depth: 0.54 mm, Hardness: 740-760 HV | Depth: 0.56 mm, Hardness: 740-755 HV | Depth: 0.54 mm, Hardness: 700-720 HV |

| Tooth Flank | Depth: 0.72 mm, Hardness: 745-760 HV | Depth: Full tooth penetration, Hardness: 745-770 HV | Depth: 0.62 mm, Hardness: 705-720 HV |

| Tooth Tip | Depth: 1.54 mm, Hardness: 740-775 HV | Depth: 4.69 mm, Hardness: 770-780 HV | Depth: 0.87 mm, Hardness: 710-730 HV |

| Fillet Area | Depth: 0.52 mm, Hardness: 740-760 HV | Depth: 0.62 mm, Hardness: 770-775 HV | Depth: 0.52 mm, Hardness: 700-720 HV |

Moreover, the revival of low-hardenability steels, such as 60T and 70T grades, offers a pathway to reduce heat treatment defects. These steels have higher carbon content without excessive cracking risk, thanks to improved metallurgical quality. By leveraging such materials, induction hardening can achieve higher surface hardness, enhancing gear strength while conserving energy through shorter heat treatment cycles.

For single-tooth contour hardening, advancements in machine functionality are vital. Replacing hydraulic drives with ball-screw systems driven by stepper or servo motors, coupled with computerized control over parameters like position, speed, power, and cooling, ensures precision and minimizes defects. This reduces the occurrence of heat treatment defects like uneven hardening or cracks, thereby improving strength consistency.

From a strength perspective, ensuring adequate hardened layer depth is paramount. Comparing hardness distribution curves, induction hardening often requires a deeper layer than carburizing to secure the transition zone. The required depth $d_{req}$ can be derived from fatigue strength criteria. For bending fatigue, the relation might be:

$$d_{req} = k \cdot \sqrt{\frac{\sigma_b}{\sigma_y}}$$

where $\sigma_b$ is the bending stress, $\sigma_y$ is the yield strength, and $k$ is a material constant. This depth must be optimized to avoid energy wastage from excessive hardening.

Carburizing of Gears: Strength Optimization and Energy Savings

Carburizing is favored for its ability to produce a hard, wear-resistant surface with a tough core, offering excellent fatigue resistance. However, it is energy-intensive due to long processing times, which are directly linked to the hardened layer depth. Therefore, optimizing this depth from a strength viewpoint can yield significant energy savings while preventing heat treatment defects like spalling or premature failure.

The determination of case depth is traditionally empirical, often based on gear module $m$ using formulas like:

$$D = (0.15 \text{ to } 0.4) \cdot m$$

where $D$ is the case depth. Industry standards, such as ISO 6336-5, provide recommendations, but the range is broad, leading to potential over-processing. For energy efficiency, it is crucial to rationalize this depth by analyzing strength requirements. Contact fatigue failures in gears can be categorized into pitting, shallow spalling, and deep spalling, each associated with specific crack origins and depths. Deep spalling, originating at the interface between the hardened layer and core, is particularly critical and dictates the necessary case depth.

To prevent such heat treatment defects, the case depth must ensure that the transition zone operates within a safe stress envelope. Consider the shear stress distribution $\tau(x)$ under load and the material strength profile $S(x)$. The safety factor $k_s$ at the transition zone can be defined as:

$$k_s = \frac{S(x_t)}{\tau(x_t)}$$

where $x_t$ is the depth of the transition zone. By analyzing this, we can adjust the carbon concentration profile to minimize depth without compromising safety. For example, if the original carbon profile $C_1(x)$ yields a safety factor $k_{s1}$, but calculations show that a modified profile $C_2(x)$ with lower carbon at depth provides $k_{s2}$ that is still adequate, the carburizing time can be reduced. This adjustment is illustrated in carbon concentration curves, where optimizing the gradient shortens process cycles by up to 20%.

The relationship between effective hardened depth and carburizing depth also offers energy-saving opportunities. The effective depth is defined by a limiting carbon content $C_{lim}$, which depends on steel composition, quenching conditions, and part size. For instance, as shown in Table 3, $C_{lim}$ varies with alloy type, affecting the required carbon profile.

| Steel Type | Limiting Carbon Content (wt.%) |

|---|---|

| 20MnCr5 | 0.45 |

| SCM420 | 0.39 |

| SAE8620 | 0.48 |

| SAE4320 | 0.28 |

| SCr420 | 0.47 |

| 20CrMnTi | 0.42 |

Furthermore, quenching speed and workpiece dimensions influence $C_{lim}$, as detailed in Table 4 and Table 5. These factors must be accounted for to avoid heat treatment defects like insufficient hardening or excessive energy use.

| Steel Type | Cooling Rate: 120°C/s (wt.%) | Cooling Rate: 18°C/s (wt.%) |

|---|---|---|

| 20MnCr5 | 0.46 | 0.50 |

| SCM420 | 0.42 | 0.49 |

| SAE8620 | 0.44 | 0.61 |

| SAE4320 | 0.38 | 0.65 |

| SCr420 | 0.43 | 0.60 |

| Sample Diameter (mm) | Limiting Carbon Content (wt.%) |

|---|---|

| 25 | 0.30 |

| 150 | 0.38 |

A practical example involves material substitution: switching from 20CrMnTi to 20CrMnMo steel. Given their different $C_{lim}$ values (0.42% vs. 0.32%), the required carbon profile for a specified effective depth of 1.6 mm can be adjusted. For 20CrMnMo, the profile can be shallower, reducing carburizing time by over 20% without inducing heat treatment defects like case crushing or fatigue failure. This underscores how material selection impacts energy efficiency.

Additionally, the interaction between case depth and core hardness is vital. A low core hardness necessitates a deeper case to compensate for reduced load-bearing capacity, increasing energy consumption. The combined effect can be modeled using fatigue life equations, such as:

$$N_f = A \cdot \left( \frac{d_c}{H_c} \right)^B$$

where $N_f$ is the fatigue life, $d_c$ is the case depth, $H_c$ is the core hardness, and $A$ and $B$ are constants. Optimizing this match can prevent heat treatment defects like spalling while curbing energy use.

Conclusion: Integrating Strength Analysis for Energy-Efficient Heat Treatment

In summary, achieving energy efficiency in gear heat treatment requires a dual focus: advancing process technologies and meticulously designing physical metallurgical factors based on strength criteria. Induction hardening, despite its energy-saving advantages, must overcome heat treatment defects like transition zone weaknesses, soft bands, and cracking through methods like dual-frequency heating and improved machine control. Carburizing, while strength-optimal, can be made more efficient by rationalizing case depth, leveraging material properties, and optimizing core hardness匹配. Both approaches benefit from a strength-driven analysis that minimizes over-processing and mitigates defects.

From my viewpoint, the future of heat treatment lies in embracing such precision-oriented strategies. By harnessing computational models, advanced materials, and real-time process control, we can significantly reduce energy consumption while enhancing gear performance. This not only addresses economic and environmental goals but also ensures reliability by preventing heat treatment defects. As the industry evolves, continued research into strength-based optimization will be key to unlocking further energy savings, making heat treatment a cornerstone of sustainable manufacturing.