In my extensive experience with bulk material handling equipment, the bucket wheel reclaimer stands as a critical and complex machine. Its operation depends on a symphony of subsystems, one of the most vital being the control cable reel drive. This system ensures continuous power and signal transmission between the moving machine and the fixed plant network. The heart of this drive is often a compact, right-angle worm gears reducer, prized for its high reduction ratio and self-locking potential in a small footprint. However, a persistent and damaging failure mode associated with axial movement in the worm shaft has been a significant operational challenge. This document details a first-person account of the problem’s root cause analysis, the engineering design of a corrective retrofit, the theoretical validation, and the successful long-term results of the implemented solution.

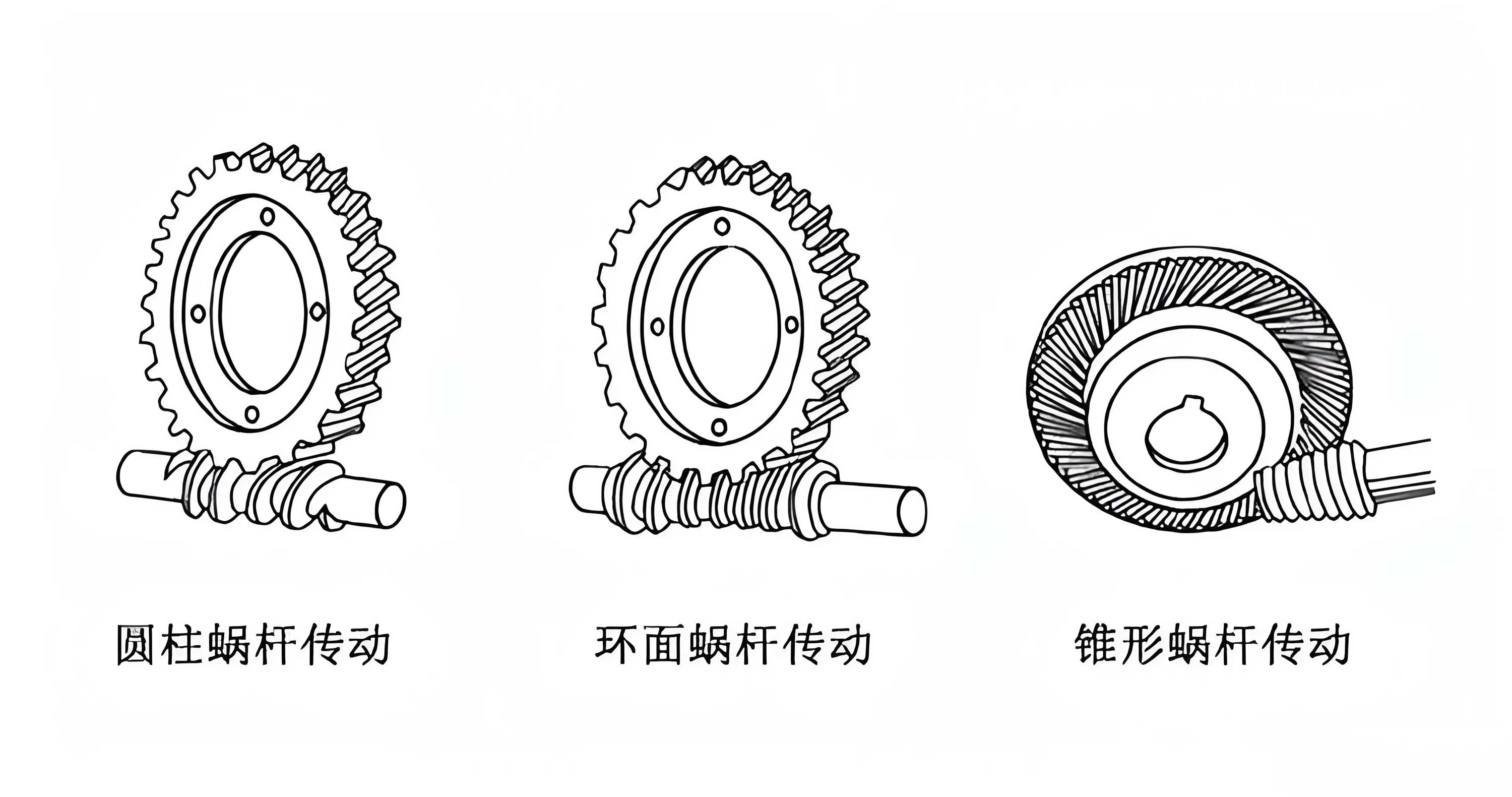

The specific reducers in question were of the worm and wheel type. Their fundamental operation is elegantly simple: a vertically mounted electric motor rotates the input worm shaft, which engages with and drives the bronze worm wheel. This wheel is directly keyed to the shaft of the control cable drum. While theoretically sound, this arrangement harbors a fundamental mechanical behavior that, if unaddressed, leads to premature failure. The meshing of the worm gears is analogous to a screw thread advancing a nut. Consequently, during power transmission, the worm shaft is subjected to a significant axial reaction force. The direction of this force depends on the direction of rotation and the helix hand of the worm. In our application, the dominant operational mode generated a consistent downward axial thrust on the worm shaft.

The original manufacturer’s design incorporated a fixation method that only restrained the worm shaft against upward movement, typically using a locknut or a similar arrangement at one end. It did not provide a dedicated, adjustable restraint against the primary downward thrust. This unopposed force led to several interconnected failure modes:

- Axial Drift and Bearing Overload: The downward force was entirely borne by the worm shaft’s support bearings (usually deep groove ball bearings) which are primarily designed to handle radial loads. While they can accommodate some axial load, constant thrust exceeding their design specification led to rapid wear, brinelling, and eventual catastrophic failure.

- Accelerated Wear of Worm Wheel: The axial movement of the worm shaft altered the optimal contact pattern between the worm threads and the wheel teeth. This misalignment caused concentrated stress, leading to accelerated wear of the softer bronze wheel. The wear debris, comprising copper and hardened steel particles, contaminated the lubricating oil, transforming it into an abrasive slurry.

- Secondary Damage Cascade: The abrasive oil circulated throughout the reducer housing, attacking all bearing surfaces and gear teeth. Furthermore, in severe cases, the cyclical stress from the unconstrained axial movement could contribute to fatigue failure, potentially leading to a complete fracture of the worm shaft, resulting in sudden and total drive failure.

The root cause was clear: the system lacked a dedicated, robust mechanism to absorb and neutralize the axial thrust generated by the worm gears pair. The solution needed to introduce a thrust-bearing assembly capable of handling the calculated load, fitting into the severely constrained space below the existing reducer housing, and allowing for precise adjustment of the worm shaft axial play (end float).

The core engineering principle behind the retrofit was to install a thrust ball bearing directly in line with the worm shaft axis, positioned to counteract the downward force. This assembly would be housed in a custom-built retrofit module attached to the bottom of the reducer housing. The key design objectives were:

1. Provide a rigid, wear-resistant thrust surface.

2. Allow for precise micrometric adjustment of the worm shaft axial position to eliminate unwanted play while preventing pre-load.

3. Facilitate easy installation and future maintenance within the existing spatial envelope.

4. Integrate seamlessly without modifying the core reducer casting or the primary worm/wheel geometry.

The design culminated in a self-contained “Anti-Thrust Module.” Its components and functions are detailed below:

| Component No. | Name | Material | Key Dimensions & Features | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mounting Flange / Housing | 45# Steel | Ø130 mm OD, 85 mm height. Bore: Ø68 mm (top, 45mm deep), M64x4 internal thread (bottom, 40mm deep). | Provides a rigid structural interface bolted to the reducer housing. Houses the entire assembly. |

| 2 | Thrust Ball Bearing | Bearing Steel | Type 51307. Bore: 35 mm, OD: 68 mm, Height: ~28 mm. | Directly absorbs and transfers the axial thrust load from the worm shaft to the housing. |

| 3 | Thrust Cap (with Spigot) | 45# Steel | Custom machined disk with a central spigot (male center) to engage the worm shaft’s center drill hole. | Transmits axial force from the worm shaft tip to the thrust bearing. Maintains alignment. |

| 4 | Lock Washer | 45# Steel | Ø70 mm, 5 mm thick. | Provides a hardened flat surface for the locknut to bear against. |

| 5 | Locknut | 45# Steel | M64x4, 50 mm thick, hexagonal. | Locks the entire adjustment in place, preventing rotation of the adjustment screw. |

| 6 | Adjustment Screw | 45# Steel | Ø64 mm, 75 mm length. M64x4 thread (top), 38 mm square drive (bottom). | Enables precise vertical adjustment of the thrust bearing pre-load/clearance. Square drive allows for easy tool access. |

The force calculations were critical for component selection, particularly the thrust bearing. The operating parameters for the reducer were as follows:

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Output Torque | $T_{max}$ | 1000 Nm (100 daNm) |

| Worm Wheel Pitch Diameter | $D_w$ | 0.250 m (estimated from geometry) |

| Worm Lead Angle | $\gamma$ | Approx. 4° (for a single-start worm) |

| Pressure Angle | $\alpha_n$ | 20° |

| Coefficient of Friction | $\mu$ | ~0.05 – 0.08 (well-lubricated steel on bronze) |

The axial force on the worm ($F_a$) generated by the output torque can be derived from the basic mechanics of worm gears. The tangential force on the worm wheel ($F_{tw}$) is:

$$F_{tw} = \frac{2 \cdot T_{max}}{D_w}$$

This tangential force on the wheel is directly related to the axial force on the worm through the lead angle and friction. A standard formula for worm drive efficiency and forces gives the axial force as:

$$F_a \approx \frac{2 \cdot T_{max}}{D_w} \cdot \frac{\cos \alpha_n \cos \gamma – \mu \sin \gamma}{\sin \gamma + \mu \cos \alpha_n \cos \gamma}$$

For a conservative estimation, assuming lower efficiency (higher friction), we can use a simplified approach. The torque on the worm wheel creates a tangential force. The reaction to this force, resolved through the worm’s thread geometry, manifests as the axial thrust. A practical estimate often used is:

$$F_a \approx \frac{2 \cdot T_{max}}{D_w \cdot \eta \cdot \tan(\gamma)}$$

Where $\eta$ is an estimated efficiency factor for the worm gears pair, typically between 0.7 and 0.85 for this type. Using $\eta = 0.75$ and $\gamma = 4°$:

$$F_a \approx \frac{2 \cdot 1000}{0.250 \cdot 0.75 \cdot \tan(4^\circ)} \approx \frac{2000}{0.250 \cdot 0.75 \cdot 0.0699} \approx \frac{2000}{0.0131} \approx 152,600 \text{ N}$$

This value seems excessively high and is likely based on an incorrect mechanical advantage perspective. The correct relationship is that the input torque on the worm ($T_{worm}$) is related to the axial force by the worm’s lead. More accurately, for a self-locking or low-efficiency worm, a significant portion of the output torque is reacted by the axial thrust. A standard formula from mechanical design handbooks for the axial force on the worm when it is the input driver is:

$$F_a = \frac{2 \cdot T_{worm}}{d_m}$$

Where $d_m$ is the mean diameter of the worm. However, we know the *output* torque. The relationship between output torque and worm axial force is:

$$T_{max} = F_a \cdot \frac{D_w}{2} \cdot \eta’$$

Where $\eta’$ is a factor relating the force transformation. Solving for $F_a$:

$$F_a = \frac{2 \cdot T_{max}}{D_w \cdot \eta’}$$

If we consider that in a heavily loaded, low-speed application, the system is near self-locking, the force transformation is direct with losses. Assuming $\eta’ \approx 1$ for a conservative load estimate on the thrust bearing:

$$F_a \approx \frac{2 \cdot 1000 \text{ Nm}}{0.250 \text{ m}} = 8000 \text{ N}$$

This 8 kN axial force is a more realistic and defendable conservative estimate for sizing the thrust bearing.

The selected thrust ball bearing, Type 51307, has a basic static load rating ($C_0$) of 100,500 N and a basic dynamic load rating (C) of 78,500 N. The static load safety factor $s_0$ is:

$$s_0 = \frac{C_0}{F_a} = \frac{100500}{8000} \approx 12.6$$

This high safety factor is appropriate for a thrust bearing in a quasi-static or low-speed application with shock loads, ensuring ample capacity and long life. The bearing’s dimensions (68mm OD) also perfectly matched the machined bore of the Mounting Flange (Component 1).

The installation and adjustment procedure was meticulous:

1. The control cable drum was disconnected, and the reducer was isolated from power.

2. The original bottom cover or fixation nut of the reducer was removed, exposing the end of the worm shaft.

3. The Mounting Flange (1) was aligned and securely bolted to the prepared mating surface on the reducer housing using four M8 bolts.

4. The Thrust Cap (3) was placed with its spigot inserted into the center drill hole of the worm shaft.

5. The Thrust Bearing (2) was placed onto the Thrust Cap, followed by the Lock Washer (4).

6. The Adjustment Screw (6) was threaded into the Mounting Flange. It was carefully turned upward until it made firm contact with the Thrust Bearing assembly, taking up the axial slack. This is the most critical step.

7. The axial end-float or “play” of the worm shaft was checked. The goal was to achieve a near-zero but slightly positive clearance (approximately 0.05 – 0.10 mm). Over-tightening (pre-load) must be absolutely avoided, as it would induce excessive friction, heat, and rapid wear in the worm gears mesh. The square drive on the Adjustment Screw allowed for fine, controlled adjustments.

8. Once the optimal clearance was set, the Locknut (5) was tightened securely against the Lock Washer (4), jamming the threads of the Adjustment Screw (6) and preventing any rotational loosening during operation.

9. The reducer was re-lubricated with fresh oil, and the system was functionally tested without load, then under gradual operational load.

The retrofit’s effectiveness was monitored over an extended period, exceeding one year of continuous operation. The results were transformative:

- Elimination of Axial Vibration and Noise: The characteristic “knocking” or “chattering” sound from the reducer, indicative of axial lash, disappeared entirely. Vibration analysis showed a dramatic reduction in axial vibration signatures.

- Bearing and Gear Life Extension: No further failures of the worm shaft support bearings occurred. Oil sample analysis conducted at regular intervals showed a marked decrease in wear metal (copper, iron) content, indicating stabilized wear rates in the worm gears mesh.

- Operational Reliability: The control cable drive system achieved 100% availability during the observation period. The unscheduled downtime previously caused by reducer failures was eliminated.

- Maintenance Cost Reduction: The costly, recurrent replacements of bearings, worm wheels, and entire reducer units ceased. Maintenance became purely preventive (scheduled oil changes and inspections).

This project underscores a critical principle in the application of worm gears reducers: their inherent generation of axial thrust must be explicitly and robustly managed in the mechanical design. The original equipment design’s oversight was the reliance on radial bearings to handle this substantial axial component. The implemented retrofit succeeded because it directly addressed the root cause physics. By introducing a dedicated, adjustable thrust-bearing system, the downward axial force was provided a direct and rigid load path into the reducer housing. This protected the radial support bearings, stabilized the worm-wheel mesh alignment, and fundamentally arrested the wear cascade.

The success of this modification offers a proven template for addressing similar issues in a wide range of industrial applications employing worm gears drives, especially in slow-speed, high-torque scenarios where axial forces are significant. The design principles of calculating the thrust load, selecting an appropriate thrust bearing with a high safety factor, and incorporating a fine-adjustment mechanism for precise end-float control are universally applicable. This engineering intervention transformed a chronic failure point into a model of reliability, delivering substantial gains in equipment uptime, maintenance cost savings, and operational safety.