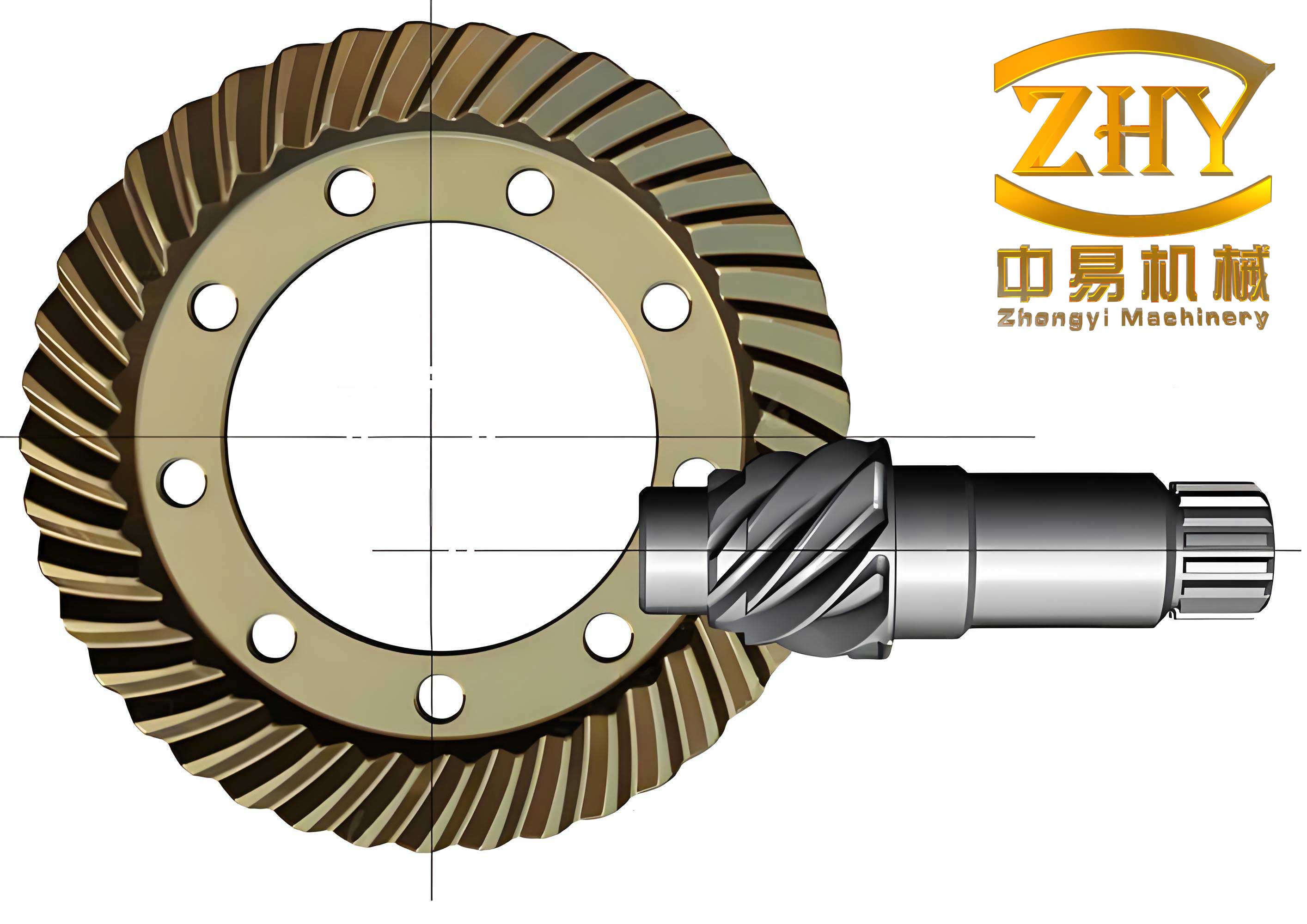

In the realm of automotive and heavy machinery transmission systems, hypoid gears play a pivotal role due to their ability to transmit power between non-intersecting axes with high efficiency and smooth operation. As an engineer deeply involved in thermal processing, I have encountered numerous challenges in heat-treating hypoid gears to meet stringent performance criteria. The core requirements for these hypoid gears include controlled case hardening depth, surface and core hardness, and minimal distortion, particularly in terms of concavity-convexity warpage. Historically, our production line relied on continuous carburizing and quenching processes, but this method often led to inconsistent results, including oxidation, decarburization, and unacceptable distortion. This narrative details our journey to overhaul the heat treatment process for hypoid gears by adopting induction heating coupled with press quenching, overcoming significant equipment limitations through innovative engineering solutions.

The traditional approach involved carburizing the hypoid gears in a continuous furnace, followed by stabilization in a constant-temperature chamber and then press quenching in batches. However, this method proved inadequate for controlling core hardness and warpage, while frequent door openings of the chamber led to oxidation and decarburization, severely impacting yield rates. The hypoid gears in question, made from 22CrMoH steel, demanded precise specifications: case effective hardening depth of 1.4–1.7 mm, surface hardness of 58–64 HRC, core hardness of 31–44 HRC, and strict limits on distortion (e.g., roundness ≤ 0.12 mm, warpage ≤ 0.10 mm). The inadequacies of the old process necessitated a shift to induction heating for its rapid, localized heating benefits, but our existing induction setup, designed for smaller components, faced power constraints when applied to these larger hypoid gears.

The induction heating system available utilized dual power sources: a left-side source rated at 150 kW for heating the gear’s outer ring, and a right-side source rated at 200 kW for the inner ring. Preliminary calculations indicated that heating a single hypoid gear to the austenitizing temperature required approximately 1084 kW, far exceeding the total 350 kW capacity. This power deficit posed two major challenges: firstly, heating times exceeded 70 seconds, increasing the risk of surface oxidation and decarburization; secondly, an concave step at the gear’s bottom hindered uniform heating, leading to insufficient austenitization and low core hardness in that region. To address these, we devised a multi-faceted strategy involving process segmentation, thermal management, and equipment modification.

We first altered the overall process flow by performing carburizing in a batch furnace, followed by slow cooling, and then conducting induction heating and press quenching on a dedicated line. This separation minimized exposure to oxidizing atmospheres. The critical innovation, however, lay in implementing a segmented heating protocol. Instead of continuous heating, we divided the process into intervals with pauses, allowing heat to conduct inward and minimizing surface degradation. The heating schedule was designed to keep initial stages below 600°C, with total heating time capped at 70 seconds. The power parameters were carefully tuned to avoid tripping the system’s protective circuits, which tended to activate near the Curie point where magnetic permeability drops sharply, causing current surges. After extensive tuning, we established initial parameters, as summarized in Table 1, which mitigated decarburization but still left unmet the core hardness requirement due to residual ferrite in the step region.

| Left Power (kW) | Right Power (kW) | Heating Time 1 (s) | Pause 1 (s) | Heating Time 2 (s) | Pause 2 (s) | Heating Time 3 (s) | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 146.8 | 185.6 | 35 | 25 | 20 | 130 | 70 | Surface decarburization controlled; martensite grade 3 at pitch circle; core hardness 36.5–37 HRC; blocky undissolved ferrite present in step area. |

The persistence of ferrite indicated inadequate heating efficiency, particularly in the gear’s concave step. In induction heating, efficiency is largely governed by magnetic flux density. To enhance this, we installed magnetic flux concentrators (often called inductors or guides) on the inner ring inductor. These concentrators direct magnetic flux inward, increasing current density on the inner surfaces and improving heating penetration. The effect was quantified through comparative trials, as shown in Table 2. The addition of concentrators boosted core hardness in the step region from 30 HRC to 42 HRC, significantly reducing ferrite content and ensuring more uniform austenitization across the hypoid gear.

| Condition | Step Core Hardness (HRC) | Metallurgical Observations |

|---|---|---|

| Without Concentrators | 30 | Carbides grade 0, martensite grade 1, retained austenite grade 1 at pitch circle; no surface decarburization; core ferrite grade 2; step area showed ferrite grades increasing from 1 to 5 from outer to inner regions. |

| With Concentrators | 42 | Carbides grade 0, martensite grade 2, retained austenite grade 2 at pitch circle; no surface decarburization; core ferrite grade 1; step area ferrite grades improved to 1 and 2. |

With these insights, we refined the heating parameters to balance power, time, and thermal diffusion. The final optimized schedule for the hypoid gears is presented in Table 3. This protocol ensured that the total heating time remained within 70 seconds, preventing oxidation, while the pauses allowed sufficient heat soak for complete transformation. The heating process can be conceptually described by the heat conduction equation, which governs temperature distribution during induction heating. For a cylindrical geometry approximating a hypoid gear, the one-dimensional transient heat conduction can be expressed as:

$$ \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \alpha \left( \frac{\partial^2 T}{\partial r^2} + \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial T}{\partial r} \right) + \frac{q_{gen}}{\rho c_p} $$

Here, \( T \) is temperature, \( t \) is time, \( \alpha \) is thermal diffusivity, \( r \) is radial coordinate, \( q_{gen} \) is the heat generation rate per unit volume from induction, \( \rho \) is density, and \( c_p \) is specific heat. The heat generation term \( q_{gen} \) is itself a function of magnetic field intensity and material properties, such as electrical conductivity and relative permeability. For hypoid gears, the complex shape necessitates numerical simulation, but the segmented approach effectively manages boundary conditions to avoid overheating surfaces while ensuring core austenitization.

| Left Power (kW) | Right Power (kW) | Heating Segment 1 (s) | Pause 1 (s) | Heating Segment 2 (s) | Pause 2 (s) | Heating Segment 3 (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 138.8 | 170.6 | 40 | 30 | 20 | 130 | 65 |

Following induction heating, the hypoid gears were immediately transferred to a press quenching fixture, which applies controlled pressure during cooling to minimize distortion. The quenching medium, typically a fast oil, extracts heat rapidly to form martensite. The success of this integrated process was validated through comprehensive testing of multiple hypoid gear samples. Metallographic examination revealed fine microstructures: at the tooth tip, needle-like martensite (grade 4, needle length ~0.0125 mm) with minor retained austenite (grade 2); at the pitch circle, martensite grade 3 and retained austenite grade 1; at the tooth root, martensite grade 4 and retained austenite grade 1. Crucially, the core exhibited a mixture of lath martensite and bainite with no free ferrite, indicating full austenitization. Hardness measurements confirmed surface hardness of 63–63.5 HRC and core hardness of 39–39.5 HRC, both within specifications. The effective case depth, determined by hardness traverse, averaged 1.65 mm, matching the target range. Distortion metrics were also satisfactory: bore roundness measured 0.10 mm, and face warpage was 0.07 mm, both below the allowable limits.

To quantify the relationship between heating parameters and case depth for hypoid gears, we can refer to empirical formulas derived from induction hardening theory. The approximate case depth \( d \) is influenced by frequency \( f \), power density \( P \), and heating time \( t \). A simplified model is:

$$ d \approx k \sqrt{\frac{\alpha t}{\pi}} $$

where \( k \) is a material constant, and \( \alpha \) is thermal diffusivity. For induction heating, the skin depth \( \delta \), which affects heating penetration, is given by:

$$ \delta = \sqrt{\frac{\rho}{\pi f \mu}} $$

Here, \( \rho \) is electrical resistivity, \( f \) is frequency, and \( \mu \) is magnetic permeability. For hypoid gears, we operate at medium frequencies (e.g., 10–50 kHz) to achieve the desired 1.4–1.7 mm case depth. Our equipment’s frequency was fixed, so we adjusted power and time to compensate. The segmented heating effectively extends the thermal diffusion time without increasing surface exposure, as the pauses allow heat to propagate inward. This can be modeled as a series of heating pulses, with total equivalent time \( t_{eq} \) calculated from the segments. For our three-segment schedule:

$$ t_{eq} = t_1 + t_2 + t_3 + \beta (p_1 + p_2) $$

where \( t_i \) are heating times, \( p_i \) are pause times, and \( \beta \) is an empirical factor accounting for heat conduction during pauses (typically 0.5–0.7). Using our values: \( t_1=40 \), \( t_2=20 \), \( t_3=65 \), \( p_1=30 \), \( p_2=130 \), and assuming \( \beta=0.6 \), we get:

$$ t_{eq} = 40 + 20 + 65 + 0.6 \times (30 + 130) = 125 + 96 = 221 \text{ seconds} $$

This equivalent time, though longer than the actual 125 seconds of active heating, explains the sufficient core austenitization without surface degradation. The pauses reduce the peak surface temperature, as heat flows inward, mitigating decarburization. The power settings were chosen to stay within the equipment’s limits while delivering enough energy. The total energy input \( E \) per hypoid gear can be estimated as:

$$ E = P_{\text{left}} \times t_{\text{left}} + P_{\text{right}} \times t_{\text{right}} $$

Since power varied per segment, we compute segment-wise. For simplicity, assuming average powers: left ~140 kW, right ~175 kW, and active heating times sum to 125 seconds, \( E \approx (140 + 175) \times 125 = 315 \times 125 = 39,375 \text{ kJ} \). This is consistent with the thermal mass of a hypoid gear weighing several kilograms.

The improvement in core hardness due to flux concentrators can be analyzed via the enhancement in magnetic flux density \( B \). With concentrators, \( B \) increases by a factor \( C \), leading to higher eddy current density \( J \), as \( J \propto B \). The heat generation rate \( q_{gen} \) is proportional to \( J^2 \), so:

$$ q_{gen, \text{with}} \approx C^2 q_{gen, \text{without}} $$

This quadratic relationship explains the dramatic improvement in heating the concave step. For our setup, \( C \) was empirically found to be around 1.3–1.5, doubling the heat generation in critical areas. This ensured that even the geometrically challenging regions of the hypoid gear reached austenitizing temperature.

Beyond metallurgical results, the economic and quality benefits are substantial. The new process for hypoid gears reduced scrap rates from over 20% to below 5%, thanks to eliminated oxidation and controlled distortion. Moreover, the induction heating line offers flexibility for different hypoid gear sizes, though parameter adjustments are needed. The press quenching fixture, designed with adjustable jaws, accommodates variations in gear diameter and face width, ensuring consistent clamping pressure during cooling. The cooling rate during press quenching is critical to avoid soft spots and minimize residual stresses. We monitor the quenching oil temperature and agitation to maintain a consistent cooling intensity, described by the heat transfer coefficient \( h \). The cooling curve should avoid the pearlite nose of the CCT diagram to achieve full martensite. For 22CrMoH steel, the critical cooling rate is approximately 30°C/s, which our oil quench provides.

In summary, the journey to optimize heat treatment for hypoid gears involved confronting power limitations, innovating with segmented heating, and enhancing magnetic flux delivery. The key takeaways are: first, segmentation of induction heating allows effective austenitization within power constraints; second, magnetic flux concentrators are invaluable for heating complex geometries like hypoid gears; third, integrated press quenching controls distortion effectively. This approach not only meets the technical specifications but also boosts productivity and consistency. Future work may explore real-time temperature monitoring with pyrometers or advanced simulation to fine-tune parameters further. The success underscores the importance of adaptive engineering in thermal processing, particularly for critical components like hypoid gears that drive modern machinery.

To encapsulate the process parameters and outcomes for hypoid gears, Table 4 provides a consolidated view of the final results across multiple samples. This data reinforces the reproducibility of the improved process.

| Sample ID | Surface Hardness (HRC) | Core Hardness (HRC) | Effective Case Depth (mm) | Tooth Tip Martensite Grade | Pitch Circle Retained Austenite Grade | Core Ferrite Grade | Bore Roundness (mm) | Face Warpage (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HG-01 | 63.2 | 39.0 | 1.64 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.06 |

| HG-02 | 63.5 | 39.5 | 1.66 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| HG-03 | 63.0 | 39.2 | 1.65 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| HG-04 | 63.3 | 39.3 | 1.67 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| HG-05 | 63.4 | 39.4 | 1.65 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.06 |

The consistent performance across samples validates the robustness of our methodology. In conclusion, the induction heat treatment and press quenching process for hypoid gears has been successfully enhanced through systematic engineering. By addressing power constraints with segmented heating and improving efficiency with magnetic flux concentrators, we achieve precise control over microstructure, hardness, and distortion. This case study highlights the synergy between theoretical principles and practical adjustments, ensuring that hypoid gears meet the demanding standards of modern applications. As technology evolves, continuous refinement will further optimize the processing of hypoid gears, paving the way for even higher performance and reliability.