In modern mechanical engineering, spiral bevel gears play a critical role in transmitting power between intersecting shafts, especially in automotive and aerospace applications. The complex geometry of spiral bevel gears, characterized by curved teeth and conical surfaces, poses significant challenges in design, manufacturing, and simulation. Traditional machining methods for spiral bevel gears rely heavily on empirical adjustments and trial-and-error processes, leading to high costs, time consumption, and quality inconsistencies. With the advent of computer-aided technologies, virtual simulation has emerged as a powerful tool to overcome these limitations. This article presents a comprehensive mathematical model for the entity modeling of spiral bevel gears, focusing on determining tooth surface boundaries, information points, and cone surfaces, followed by implementation using NURBS-based surface fitting and OpenGL for visualization. The goal is to enable accurate virtual testing and simulation of spiral bevel gears, reducing reliance on physical prototypes and optimizing manufacturing parameters.

The core of our approach lies in developing a robust mathematical framework that accurately represents the three-dimensional geometry of spiral bevel gears. We start by defining the tooth surface as a parametric surface dependent on machine tool settings, such as the cradle rotation angle and cone generatrix angle. From there, we derive algorithms to compute intersection curves with key conical surfaces—namely, the back cone, root cone, front cone, and face cone—which collectively bound the tooth. Using these boundaries, we discretize the tooth surface into information points and employ non-uniform rational B-splines (NURBS) for smooth surface approximation. This model not only facilitates high-fidelity entity modeling but also supports virtual assembly and dynamic meshing analysis of spiral bevel gear pairs. Throughout this discussion, we emphasize the importance of spiral bevel gears in transmission systems and highlight how our methodology enhances their design and manufacturing.

To begin, we establish the parametric equations for the tooth surface of spiral bevel gears. The surface can be expressed as a function of two parameters: \(\theta_F\), representing the rotation angle of the cone generatrix, and \(\psi_F\), denoting the cradle rotation angle in the machining simulation. The tooth surface equations are given by:

$$ x = f_1(\theta_F, \psi_F) $$

$$ y = f_2(\theta_F, \psi_F) $$

$$ z = f_3(\theta_F, \psi_F) $$

These equations form the basis for determining the tooth boundaries and internal points. The boundaries are defined by the intersection of the tooth surface with four conical surfaces: back cone, root cone, front cone, and face cone. Collectively, these are referred to as the “five cones and four angles” in spiral bevel gear terminology. The intersection curves, labeled \(l_1\), \(l_2\), \(l_3\), and \(l_4\), correspond to the back cone, root cone, front cone, and face cone intersections, respectively. Accurately computing these curves is essential for delineating the tooth profile.

We derive the conical surface equations in a unified coordinate system. For instance, the back cone equation is formulated as:

$$ x_1 = u_1 \cos \delta_1 \cos \theta_1 \cos \phi_1 – u_1 \cos \delta_1 \sin \theta_1 \sin \phi_1 $$

$$ y_1 = u_1 \cos \delta_1 \cos \theta_1 \sin \phi_1 + u_1 \cos \delta_1 \sin \theta_1 \cos \phi_1 $$

$$ z_1 = u_1 \sin \delta_1 + \frac{L_a}{\cos \delta_1} $$

Similarly, the root cone, front cone, and face cone equations are expressed with parameters \(u_i\) and \(\theta_i\) (where \(i = 2, 3, 4\)), incorporating gear design parameters such as pitch angle \(\delta_1\), root angle \(\delta_{b1}\), face angle \(\delta_{a1}\), and cone distances. By solving the system of equations between the tooth surface and each cone surface, we obtain the intersection curves. The unknown variables include \(u_i\), \(\theta_i\), \(\psi_F\), and \(\theta_F\). To solve these, we treat \(u_i\) as a cyclic variable, iterating from initial to terminal values corresponding to the vertices of the tooth surface. This yields discrete points along the boundaries, which are connected to form the curves \(l_1\) to \(l_4\).

The next step involves computing information points on the tooth surface. These points are essential for constructing a wireframe model and subsequent surface fitting. The tooth surface is discretized along the tooth height direction between boundaries \(l_2\) and \(l_4\). We define a grid of points \(P_{i,j}\), where \(i\) indexes points along the tooth length and \(j\) indexes points along the tooth height. For example, points \(P_{i,0}\) and \(P_{i,7}\) lie on \(l_2\) and \(l_4\), respectively. The parameters \(\psi_F\) and \(\theta_F\) for intermediate points \(P_{i,j}\) (with \(j = 1\) to \(6\)) are calculated using linear interpolation:

$$ \psi_{F_{i,j}} = \psi_{F_{i,0}} + \frac{\psi_{F_{i,7}} – \psi_{F_{i,0}}}{7} j $$

$$ \theta_{F_{i,j}} = \theta_{F_{i,0}} + \frac{\theta_{F_{i,7}} – \theta_{F_{i,0}}}{7} j $$

Substituting these parameter values into the tooth surface equations yields the coordinates of \(P_{i,j}\). This process is repeated for all \(i\) values (e.g., \(i = 1\) to \(14\)) to cover the entire tooth surface. The same method applies to both convex and concave sides of spiral bevel gears, ensuring a comprehensive point cloud for modeling.

In addition to the tooth surface, we compute points on the face cone and root cone surfaces. These cones form the external boundaries of the gear tooth. Points on the face cone, such as \(P_{i,8}\) and \(P_{i,9}\), are derived from intersection points \(P_{i,7}\) and \(P_{i,10}\), which lie on a circular arc when projected onto a plane perpendicular to the gear axis. Let \(r\) be the radius of this arc, and let \(\alpha_{i,7}\) and \(\alpha_{i,10}\) be the angles from the center to \(P_{i,7}\) and \(P_{i,10}\), respectively. The intermediate angles are:

$$ \alpha_{i,j} = \alpha_{i,7} + \frac{\alpha_{i,10} – \alpha_{i,7}}{3} (j – 7) $$

Thus, the coordinates for \(P_{i,8}\) and \(P_{i,9}\) are:

$$ x_{i,j} = r \sin \alpha_{i,j} $$

$$ y_{i,j} = r \cos \alpha_{i,j} $$

$$ z_{i,j} = z_i $$

Similarly, points on the root cone, like \(P_{i,18}\) and \(P_{i,19}\), are computed using analogous geometric relationships. This ensures that all conical surfaces are accurately represented in the model.

With the boundary curves and information points established, we proceed to entity generation. The entity of spiral bevel gears comprises multiple surfaces: tooth surface, back cone, root cone, front cone, and face cone. To digitally represent this entity, we use surface trimming and stitching techniques. Rather than relying on commercial CAD software for secondary development, we employ OpenGL as a graphics development environment and NURBS for surface approximation. NURBS offer flexibility in representing complex curves and surfaces with high precision, making them ideal for spiral bevel gears. The process involves defining control points, weights, and knot vectors based on the computed information points, then generating smooth surfaces through NURBS interpolation or fitting.

Our implementation in C++ with OpenGL allows direct control over graphics rendering, enhancing portability and robustness. The algorithm for entity modeling can be summarized in the following steps, which we encapsulate in a table for clarity:

| Step | Description | Mathematical Basis |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Define tooth surface parametric equations | $$ x = f_1(\theta_F, \psi_F), y = f_2(\theta_F, \psi_F), z = f_3(\theta_F, \psi_F) $$ |

| 2 | Compute intersection curves with conical surfaces | Solve systems of equations for back, root, front, and face cones |

| 3 | Discretize tooth surface into information points | Linear interpolation of parameters: $$ \psi_{F_{i,j}} = \psi_{F_{i,0}} + \frac{\psi_{F_{i,7}} – \psi_{F_{i,0}}}{7} j $$ |

| 4 | Calculate points on face and root cones | Geometric arc interpolation: $$ \alpha_{i,j} = \alpha_{i,7} + \frac{\alpha_{i,10} – \alpha_{i,7}}{3} (j – 7) $$ |

| 5 | Generate entity using NURBS and OpenGL | Surface fitting with control points and knot vectors |

To validate our model, we apply it to a practical example: the spiral bevel gear pair from the CA-10B automobile rear axle. This gear pair consists of a pinion and a gear with specific design parameters. The key parameters are listed in the table below, which illustrates the geometric characteristics of spiral bevel gears:

| Parameter | Pinion (Small Gear) | Gear (Large Gear) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Teeth | 11 | 25 |

| Shaft Angle | 90° | |

| Module (mm) | 9 | |

| Hand of Spiral | Left | Right |

| Spiral Angle | 35° | 35° |

| Whole Depth (mm) | 16.992 | 16.992 |

| Pitch Angle | 23.75° | 66.25° |

| Root Angle | 20.74° | 60.57° |

| Face Angle | 29.43° | 69.26° |

| Addendum (mm) | 10.53 | 4.77 |

| Dedendum (mm) | 6.462 | 12.222 |

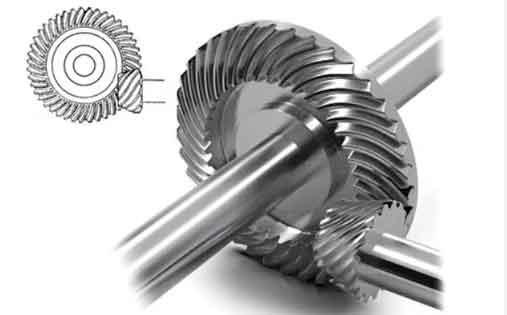

Using these parameters, we implement our algorithm in a C++ program with OpenGL. The program computes the tooth surface boundaries, information points, and cone surfaces, then renders the three-dimensional entities of the pinion and gear. The visualization showcases the intricate geometry of spiral bevel gears, including curved teeth and conical features. Below is an illustrative image of a spiral bevel gear, which highlights the complex tooth form that our model accurately captures:

The entity modeling of spiral bevel gears enables various advanced analyses. For instance, we can simulate the meshing process of gear pairs by assembling the pinion and gear entities in virtual space. Using OpenGL’s transformation functions, we position the gears according to their shaft angles and center distances. Then, by applying rotational motions, we observe tooth contact patterns and transmission errors. This virtual testing mimics physical roll tests but without material waste or time delays. Moreover, the NURBS-based representation allows for smooth surface interactions, essential for accurate contact mechanics simulations.

One significant advantage of our approach is its adaptability to computer-aided manufacturing (CAM). The mathematical model can generate tool paths for machining spiral bevel gears on multi-axis CNC machines. By inversely calculating the machine tool settings from the tooth surface equations, we can optimize cutting parameters and reduce setup times. This bridges the gap between design and production, enhancing the efficiency of manufacturing spiral bevel gears. Additionally, the model supports tolerance analysis and quality control by comparing virtual entities with design specifications.

In terms of computational efficiency, our algorithms are designed to balance accuracy and performance. The use of parametric equations and linear interpolation simplifies point calculation, while NURBS provide compact surface representations. OpenGL accelerates rendering through hardware acceleration, enabling real-time visualization of complex gear geometries. For large-scale simulations, such as dynamic analysis of entire transmission systems, the model can be integrated with finite element methods or multi-body dynamics software. This expands the applicability of spiral bevel gear modeling beyond mere visualization to full-scale engineering analysis.

The implications of this research are profound for industries relying on spiral bevel gears. In automotive applications, such as differential systems, accurate gear modeling improves durability and noise reduction. In aerospace, where weight and precision are critical, virtual testing reduces the need for physical prototypes, saving costs and time. The methodology also facilitates educational purposes, allowing students and engineers to explore gear geometry without access to expensive hardware. As virtual reality technologies advance, our model could be extended to immersive training environments for gear design and manufacturing.

To further elucidate the mathematical foundations, we delve into the derivation of tooth surface equations for spiral bevel gears. These equations originate from the kinematics of gear generation using face-milling or face-hobbing processes. The machine tool settings, including cutter geometry, machine root angle, and cradle rotation, are encoded in the parameters \(\theta_F\) and \(\psi_F\). A general form of the tooth surface equation can be expressed as a transformation of cutter coordinates to gear coordinates:

$$ \mathbf{r}(\theta_F, \psi_F) = \mathbf{T}(\psi_F) \cdot \mathbf{C}(\theta_F) $$

where \(\mathbf{T}\) is the transformation matrix accounting for cradle rotation and machine adjustments, and \(\mathbf{C}\) is the cutter surface equation. For a spiral bevel gear with curved teeth, the cutter surface is typically a circular arc or a tapered surface. The explicit equations involve trigonometric functions and design parameters. For example, the coordinates of a point on the tooth surface might be:

$$ x = R_c \cos(\theta_F) \cos(\psi_F) – R_c \sin(\theta_F) \sin(\psi_F) \sin(\beta) $$

$$ y = R_c \cos(\theta_F) \sin(\psi_F) + R_c \sin(\theta_F) \cos(\psi_F) \sin(\beta) $$

$$ z = R_c \sin(\theta_F) \cos(\beta) + L $$

Here, \(R_c\) is the cutter radius, \(\beta\) is the spiral angle, and \(L\) is an offset distance. These equations are simplified; actual models incorporate more complex factors like tooth profile modifications and ease-off topographies. Nonetheless, they capture the essence of spiral bevel gear geometry.

The intersection with conical surfaces requires solving nonlinear equations. We employ numerical methods such as Newton-Raphson iteration to find solutions for \(u_i\) and \(\theta_i\). For instance, to find the intersection with the back cone, we set the tooth surface equations equal to the back cone equations and iterate over \(u_1\). The convergence criteria ensure accuracy within tolerable limits, typically \(10^{-6}\) mm for coordinate values. This numerical robustness is crucial for high-precision applications of spiral bevel gears.

Regarding surface fitting, NURBS are defined by:

$$ \mathbf{S}(u,v) = \frac{\sum_{i=0}^n \sum_{j=0}^m N_{i,p}(u) N_{j,q}(v) w_{i,j} \mathbf{P}_{i,j}}{\sum_{i=0}^n \sum_{j=0}^m N_{i,p}(u) N_{j,q}(v) w_{i,j}} $$

where \(N_{i,p}\) and \(N_{j,q}\) are B-spline basis functions of degrees \(p\) and \(q\), \(\mathbf{P}_{i,j}\) are control points, and \(w_{i,j}\) are weights. We determine control points from the information points \(P_{i,j}\) using least-squares approximation. The knot vectors are chosen based on parameter distribution, ensuring smoothness across the tooth surface. OpenGL’s NURBS rendering functions then display the surface with lighting and shading effects, enhancing visual realism.

In conclusion, our mathematical model for entity modeling of spiral bevel gears provides a comprehensive framework for virtual design and simulation. By determining tooth boundaries, information points, and cone surfaces through systematic algorithms, and employing NURBS and OpenGL for implementation, we achieve accurate and efficient three-dimensional representations. The application to a real-world gear pair demonstrates practicality, while the methodology offers benefits such as reduced prototyping costs, optimized manufacturing, and enhanced analysis capabilities. Future work may include extending the model to hypoid gears, incorporating dynamic loading effects, and integrating with cloud-based simulation platforms. As industries continue to seek efficiency and innovation, the role of advanced modeling for spiral bevel gears will only grow in importance.

Throughout this article, we have emphasized the significance of spiral bevel gears in mechanical transmissions. Their complex geometry necessitates sophisticated modeling techniques, and our approach addresses this need through a blend of mathematical rigor and computational graphics. The repeated focus on spiral bevel gears underscores their centrality in our discussion, from boundary determination to entity generation. By leveraging virtual technologies, we pave the way for more resilient and economical production of these critical components, ultimately advancing the field of gear engineering.