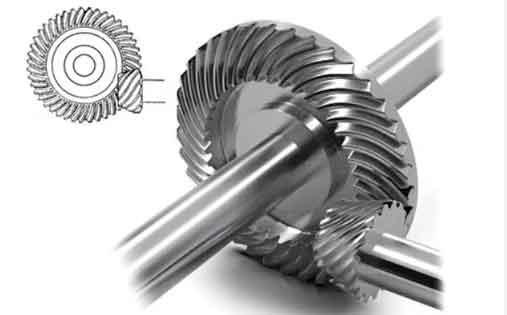

In the field of mechanical engineering, spiral bevel gears play a critical role in transmitting power between intersecting shafts, especially in high-speed and heavy-duty applications such as aerospace and automotive systems. The complex geometry of spiral bevel gears, characterized by curved teeth and angled axes, enables smooth and efficient torque transmission. However, under severe operating conditions, these gears are prone to failure modes like scuffing or scoring, which are often triggered by excessive surface temperatures at the contact points. Understanding and predicting the flash temperature—the transient temperature rise at the gear tooth surface during meshing—is essential for enhancing the scuffing load capacity and reliability of spiral bevel gears. Traditional methods, such as the Block flash temperature formula, have been widely used, but they often assume full elastohydrodynamic lubrication (EHL), neglecting the mixed lubrication regimes that occur in practice. In reality, gear contacts operate under mixed EHL conditions, where both boundary lubrication and full EHL coexist due to surface roughness and varying loads. This article aims to delve into a comprehensive analysis of surface flash temperature for spiral bevel gears under mixed elastohydrodynamic lubrication, improving calculation accuracy by incorporating average friction coefficients derived from realistic lubrication states. Through geometric and loaded tooth contact analysis (TCA and LTCA), we will explore the effects of contact path inclination and length on flash temperature distribution, ultimately providing insights for design optimization. The study emphasizes the importance of accurate flash temperature prediction to prevent scuffing failures in spiral bevel gears, ensuring their longevity and performance in demanding environments.

The foundational approach for evaluating scuffing resistance in gears is the flash temperature method, with the Block formula serving as a cornerstone. The original Block flash temperature formula is expressed as:

$$ \Theta_{fl} = 0.62 C_m \mu_m \omega_{bn}^{3/4} E_r^{1/4} \left( \frac{1}{\rho_1} + \frac{1}{\rho_2} \right)^{1/4} \frac{|v_{1s} – v_{2s}|}{B_{m1} v_{1s} + B_{m2} v_{2s}} $$

where \( \Theta_{fl} \) is the flash temperature at the contact point in degrees Celsius, \( C_m = 1.5 \) is a weighting factor, \( \mu_m \) is the average local friction coefficient along the contact path, \( \omega_{bn} \) is the unit load per face width in N/mm, \( E_r \) is the reduced elastic modulus in N/mm², \( \rho_1 \) and \( \rho_2 \) are the radii of curvature at the contact point for the pinion and gear in mm, \( v_{1s} \) and \( v_{2s} \) are the tangential velocities at the contact point for the pinion and gear in mm/s, and \( B_{m1} \) and \( B_{m2} \) are the thermal contact coefficients for the pinion and gear in N/(mm·s¹/²·°C). While this formula provides a useful framework, its accuracy is limited by the assumption of a constant average friction coefficient derived solely from full EHL conditions. In practice, spiral bevel gears operate under mixed elastohydrodynamic lubrication, where the lubrication state transitions between boundary and full film regimes due to factors like surface roughness, load variations, and speed changes. This mixed lubrication state significantly influences the friction behavior, necessitating a more nuanced approach to calculating the average friction coefficient.

To address this, we derive the average friction coefficient under mixed EHL conditions by considering the contributions from both boundary lubrication and full EHL. According to the mixed lubrication model, the normal load \( F_n \) and tangential friction force \( F_t \) can be decomposed as:

$$ F_n = F^e_n + F^b_n $$

$$ F_t = F^e_t + F^b_t $$

Here, \( F^e_n \) and \( F^e_t \) represent the normal load and friction force in the full EHL regime, while \( F^b_n \) and \( F^b_t \) correspond to the boundary lubrication regime. Based on research by Zhu and Hu, the normal load in full EHL is related to the total load by a factor dependent on the film thickness ratio \( \epsilon \), defined as \( \epsilon = t_{ch} / \mu \), where \( t_{ch} = x t_h \) is the corrected lubricant film thickness considering thermal effects, \( x \) is a thermal correction coefficient, \( t_h \) is the average film thickness, and \( \mu = \sqrt{\mu_1^2 + \mu_2^2} \) is the equivalent surface roughness with \( \mu_1 \) and \( \mu_2 \) being the roughness values of the pinion and gear surfaces. Specifically:

$$ F^e_n = 1.21 \epsilon^{0.64} (1 + 0.37 \epsilon^{1.26}) F_n = \sigma F_n $$

Thus, \( F^b_n = (1 – \sigma) F_n \). The friction forces in each regime follow Coulomb’s law: \( F^e_t = f^e F^e_n \) and \( F^b_t = f^b F^b_n \), where \( f^e \) and \( f^b \) are the average friction coefficients for full EHL and boundary lubrication, respectively. Combining these, the overall average sliding friction coefficient \( f \) under mixed lubrication is:

$$ f = \sigma f^e + (1 – \sigma) f^b $$

For full EHL, the average friction coefficient \( f_n \) can be derived from studies by Winter and Michaelis. The relationship between \( f_n \) and \( f^e \) is influenced by the unit load \( W_l \), leading to:

$$ \frac{f_n}{f^e} = \frac{F_n^{0.2}}{(F^e_n)^{0.2}} = \frac{F_n^{0.2}}{(\sigma F_n)^{0.2}} = \frac{1}{\sigma^{0.2}} $$

Hence, \( f^e = \sigma^{0.2} f_n \). For boundary lubrication, extensive research indicates that \( f^b \) varies within a narrow range of 0.07 to 0.15; we adopt a constant value of 0.11 as a reasonable average. Substituting into the expression for \( f \), we obtain:

$$ f = \sigma^{1.2} f_n + (1 – \sigma) f_b $$

This refined average friction coefficient accounts for the mixed lubrication state, thereby enhancing the precision of the Block flash temperature formula when applied to spiral bevel gears.

To compute the flash temperature for spiral bevel gears, we must also determine the geometric parameters, such as the radii of curvature and tangential velocities at each contact point along the meshing path. This requires integration with tooth contact analysis (TCA) and loaded tooth contact analysis (LTCA) for spiral bevel gears. TCA provides the kinematic and geometric details of the meshing process, including the contact path, while LTCA yields the load distribution along this path. For spiral bevel gears, the contact ellipse is typically elongated, with the major axis much longer than the minor axis. Therefore, the curvature along the major axis is negligible, and we focus on the curvature along the minor axis. At a given contact point \( M_0 \), let \( K_{11} \) and \( K_{12} \) be the principal curvatures of the pinion surface, with corresponding principal directions \( e_{11} \) and \( e_{12} \), and \( K_{21} \) and \( K_{22} \) for the gear surface, with directions \( e_{21} \) and \( e_{22} \). The angle between \( e_{11} \) and the major axis of the contact ellipse is \( \alpha_1 \), and the angle between \( e_{21} \) and \( e_{11} \) is \( \varepsilon_{12} \). These parameters are obtained from TCA. Using Euler’s formula, the radii of curvature \( \rho_1 \) and \( \rho_2 \) are calculated as:

$$ \rho_1 = \frac{1}{K_{11} \sin^2 \alpha_1 + K_{12} \cos^2 \alpha_1} $$

$$ \rho_2 = \frac{1}{K_{21} \sin^2 (\alpha_1 + \varepsilon_{12}) + K_{22} \cos^2 (\alpha_1 + \varepsilon_{12})} $$

The tangential velocities at the contact point are derived from the kinematic analysis. In a coordinate system \( S_1 \) fixed to the pinion, the position vector of the contact point is \( \mathbf{r}_1 \), and the unit normal vector is \( \mathbf{n}_1 \). Similarly, in system \( S_2 \) fixed to the gear, we have \( \mathbf{r}_2 \) and \( \mathbf{n}_2 \). The angular velocity vectors are \( \boldsymbol{\omega}_1 \) for the pinion and \( \boldsymbol{\omega}_2 \) for the gear. The absolute velocities \( \mathbf{v}_1 \) and \( \mathbf{v}_2 \) are:

$$ \mathbf{v}_1 = \boldsymbol{\omega}_1 \times \mathbf{r}_1 $$

$$ \mathbf{v}_2 = \boldsymbol{\omega}_2 \times \mathbf{r}_2 $$

The tangential velocities, which are the components of these absolute velocities perpendicular to the surface normal, are:

$$ \mathbf{v}_{1t} = \mathbf{v}_1 – (\mathbf{v}_1 \cdot \mathbf{n}_1) \mathbf{n}_1 $$

$$ \mathbf{v}_{2t} = \mathbf{v}_2 – (\mathbf{v}_2 \cdot \mathbf{n}_2) \mathbf{n}_2 $$

By transforming these into a common coordinate system, such as the machine coordinate system \( S_h \), we obtain \( \mathbf{v}_{1h} \) and \( \mathbf{v}_{2h} \), the tangential velocities used in the flash temperature formula. The unit load \( \omega_{bn} \) is determined from LTCA, which calculates the load distribution based on the gear geometry and applied torque. With these inputs, the flash temperature along the contact path can be evaluated for spiral bevel gears under mixed EHL conditions.

To illustrate the application of this methodology, consider a case study involving a pair of spiral bevel gears with parameters summarized in Table 1. The gears operate at a pinion speed of 6000 r/min, transmitting a power of 667 kW. The bulk temperature is 100°C, and the dynamic viscosity of the lubricant at this temperature is 10 mPa·s. The reduced elastic modulus is 225,694.4 N/mm², and the surface roughness for both pinion and gear before run-in is 0.35 μm. The thermal contact coefficients are 13.8 N/(mm·s¹/²·°C) for both members. We analyze three different contact path configurations by varying the angle between the contact path and the gear root cone: 60°, 35°, and 18°. The flash temperature distribution along the contact path is computed for each case, and the results are discussed in terms of maximum flash temperature and its location.

| Parameter | Pinion | Gear |

|---|---|---|

| Number of teeth, Z | 23 | 65 |

| Module at large end, m (mm) | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| Face width, B (mm) | 37 | 37 |

| Normal pressure angle, α (°) | 22.5 | 22.5 |

| Mean spiral angle, β (°) | 35 | 35 |

| Shaft angle, Σ (°) | 90 | |

| Hand of spiral | Right | Left |

| Working depth, h_w (mm) | 6.63 | |

| Outer cone distance, A_w (mm) | 134.45 | |

| Pitch angle, γ | 19°29′ | 70°31′ |

| Face angle, γ_f | 21°7′ | 71°13′ |

| Root angle, γ_r | 18°47′ | 68°53′ |

| Addendum, h_t (mm) | 4.65 | 1.98 |

| Dedendum, h_r (mm) | 2.72 | 5.38 |

| Clearance, h_c (mm) | 0.73 | |

The computed results for the three contact path angles are presented in Table 2, which summarizes key outcomes including the maximum flash temperature, its location, the actual contact ratio, and the average unit load. For each case, the contact pattern, tangential velocities, load distribution, and flash temperature profile along the path are analyzed. In all scenarios, the flash temperature is zero at the point where the contact path intersects the pitch cone, as the tangential velocities of the pinion and gear are equal in magnitude but opposite in direction, resulting in no sliding. The maximum flash temperature occurs in the middle of the approach path due to the larger sliding velocity difference on the approach side compared to the recess side, coupled with symmetrical load distribution from LTCA. As the contact path inclination increases (i.e., the angle decreases from 60° to 18°), the path length extends, leading to a higher actual contact ratio and a reduction in load per contact point. Consequently, the maximum flash temperature decreases significantly.

| Contact Path Angle (°) | Maximum Flash Temperature (°C) | Location | Actual Contact Ratio | Average Unit Load (N/mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 102.9 | Middle of approach path | 2.0 | 285.6 |

| 35 | 93.3 | Middle of approach path | 2.2 | 259.8 |

| 18 | 81.4 | Middle of approach path | 2.6 | 220.3 |

The reduction in maximum flash temperature with increasing contact path inclination and length is quantitatively expressed as follows: for the 35° case compared to 60°, the decrease is approximately 9.3%, and for the 18° case compared to 60°, it is about 20.9%. This trend highlights the importance of contact path design in managing thermal loads in spiral bevel gears. The underlying mechanisms can be explained through the flash temperature formula. The term \( \omega_{bn}^{3/4} \) reflects the load dependence, and as the contact ratio rises, \( \omega_{bn} \) diminishes due to load sharing among more teeth. Additionally, the radii of curvature \( \rho_1 \) and \( \rho_2 \) change with the contact point position, affecting the \( (1/\rho_1 + 1/\rho_2)^{1/4} \) factor. However, the dominant effect comes from the load reduction, which outweighs variations in curvature and tangential velocities. The tangential velocity difference \( |v_{1s} – v_{2s}| \) remains relatively stable across different paths, but the denominator \( B_{m1} v_{1s} + B_{m2} v_{2s} \) may slightly increase with path length due to higher rolling velocities, further contributing to temperature reduction.

To delve deeper into the analysis, we can express the relationship between contact path geometry and flash temperature using derived formulas. The actual contact ratio \( \varepsilon_{\gamma} \) for spiral bevel gears is influenced by the contact path length \( L_c \) and the base pitch \( p_b \). For orthogonal spiral bevel gears (shaft angle 90°), the contact ratio can be approximated as:

$$ \varepsilon_{\gamma} = \frac{L_c}{p_b \cos \beta_m} $$

where \( \beta_m \) is the mean spiral angle. The unit load \( \omega_{bn} \) is related to the total transmitted load \( F_t \) and the contact ratio by:

$$ \omega_{bn} = \frac{F_t}{B \varepsilon_{\gamma}} $$

Substituting into the Block formula, we see that \( \Theta_{fl} \propto \omega_{bn}^{3/4} \propto \varepsilon_{\gamma}^{-3/4} \). Thus, increasing the contact ratio through longer or more inclined contact paths directly reduces flash temperature. Moreover, the average friction coefficient \( f \) under mixed EHL also depends on the load and film thickness ratio. The film thickness ratio \( \epsilon \) is given by:

$$ \epsilon = \frac{x t_h}{\sqrt{\mu_1^2 + \mu_2^2}} $$

where \( t_h \) can be estimated using the Hamrock-Dowson formula for EHL film thickness:

$$ t_h = 2.69 R’ U^{0.67} G^{0.53} W^{-0.067} (1 – 0.61 e^{-0.73 \kappa}) $$

Here, \( R’ \) is the effective radius of curvature, \( U \) is the speed parameter, \( G \) is the material parameter, \( W \) is the load parameter, and \( \kappa \) is the ellipticity ratio. For spiral bevel gears, these parameters vary along the contact path, making the computation iterative. However, for design purposes, average values can be used. The factor \( \sigma \) in the average friction coefficient is then:

$$ \sigma = 1.21 \epsilon^{0.64} (1 + 0.37 \epsilon^{1.26}) $$

As the load decreases with higher contact ratio, \( W \) decreases, leading to a larger \( t_h \) and thus a higher \( \epsilon \). This increases \( \sigma \), meaning the full EHL contribution becomes more dominant. Since \( f^e \) is generally lower than \( f^b \), the overall friction coefficient \( f \) may decrease, further reducing flash temperature. This interplay between lubrication regime and load distribution underscores the complexity of thermal analysis in spiral bevel gears.

In practice, the design of spiral bevel gears often involves optimizing the contact path to balance strength, noise, and thermal performance. The inclination of the contact path relative to the root cone is controlled by parameters such as the spiral angle, pressure angle, and cutter geometry. By using advanced manufacturing techniques like Gleason or Klingelnberg methods, engineers can tailor the contact pattern to achieve desired characteristics. For high-speed applications, where scuffing is a major concern, a longer and more inclined contact path is beneficial as it lowers the maximum flash temperature and enhances scuffing resistance. However, this must be balanced against other factors like bending stress and contact stress, which may be affected by changes in load distribution. Finite element analysis (FEA) and dynamic simulations can complement the flash temperature analysis to ensure comprehensive design validation.

The implications of this research extend beyond academic interest to real-world engineering. In aerospace systems, spiral bevel gears are used in helicopter transmissions and auxiliary power units, where failure can have catastrophic consequences. By accurately predicting flash temperature under mixed lubrication, designers can select appropriate materials, lubricants, and cooling strategies. For instance, surface treatments like nitriding or coating with low-friction materials can reduce the boundary friction coefficient \( f^b \), thereby lowering overall flash temperature. Similarly, synthetic lubricants with high viscosity indices and extreme pressure additives can improve the EHL film thickness, shifting the lubrication toward full film regimes. The methodology presented here provides a tool for evaluating these effects quantitatively.

To further illustrate the computational process, let’s outline the step-by-step procedure for flash temperature analysis of spiral bevel gears under mixed EHL:

- Input Parameters: Gather gear geometry (Table 1), operating conditions (speed, power, bulk temperature), lubricant properties (viscosity, pressure-viscosity coefficient), and surface roughness data.

- TCA: Perform tooth contact analysis to determine the contact path, contact points, principal curvatures, principal directions, and angles like \( \alpha_1 \) and \( \varepsilon_{12} \).

- LTCA: Conduct loaded tooth contact analysis to obtain the load distribution \( \omega_{bn} \) along the contact path.

- Curvature Radius Calculation: For each contact point, compute \( \rho_1 \) and \( \rho_2 \) using Euler’s formula as shown above.

- Tangential Velocity Calculation: Determine \( \mathbf{v}_1 \) and \( \mathbf{v}_2 \) from kinematics, then derive tangential components \( v_{1s} \) and \( v_{2s} \).

- Lubrication Analysis: Calculate the film thickness ratio \( \epsilon \) using EHL formulas, then compute \( \sigma \) and the average friction coefficient \( f \) from mixed lubrication model.

- Flash Temperature Computation: Apply the modified Block formula with \( f \) as \( \mu_m \), along with other parameters, to find \( \Theta_{fl} \) at each contact point.

- Results Interpretation: Identify maximum flash temperature, its location, and assess scuffing risk based on allowable temperature limits.

This procedure can be implemented in software tools for automated analysis, enabling iterative design optimizations. For example, Table 3 summarizes typical values of key parameters at a sample contact point for the spiral bevel gear pair with a contact path angle of 35°.

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Pinion curvature radius, \( \rho_1 \) | 45.2 | mm |

| Gear curvature radius, \( \rho_2 \) | 120.7 | mm |

| Pinion tangential velocity, \( v_{1s} \) | 12,540 | mm/s |

| Gear tangential velocity, \( v_{2s} \) | 4,320 | mm/s |

| Unit load, \( \omega_{bn} \) | 260.5 | N/mm |

| Film thickness ratio, \( \epsilon \) | 1.8 | – |

| Sigma factor, \( \sigma \) | 0.75 | – |

| Average friction coefficient, \( f \) | 0.065 | – |

| Flash temperature, \( \Theta_{fl} \) | 93.3 | °C |

The flash temperature formula can be rewritten to explicitly include the mixed lubrication effects by substituting \( \mu_m = f \):

$$ \Theta_{fl} = 0.62 C_m \left[ \sigma^{1.2} f_n + (1 – \sigma) f_b \right] \omega_{bn}^{3/4} E_r^{1/4} \left( \frac{1}{\rho_1} + \frac{1}{\rho_2} \right)^{1/4} \frac{|v_{1s} – v_{2s}|}{B_{m1} v_{1s} + B_{m2} v_{2s}} $$

This expression highlights how the lubrication regime, through \( \sigma \) and \( f_b \), directly influences the temperature rise. For spiral bevel gears, the thermal contact coefficients \( B_{m1} \) and \( B_{m2} \) are crucial as they represent the heat dissipation capacity of the materials. They are defined as \( B_m = \sqrt{\lambda \rho c} \), where \( \lambda \) is thermal conductivity, \( \rho \) is density, and \( c \) is specific heat. Using high-conductivity materials like copper alloys for gears can increase \( B_m \), thereby reducing flash temperature according to the denominator in the formula.

In conclusion, the analysis of surface flash temperature for spiral bevel gears under mixed elastohydrodynamic lubrication offers a refined approach to predicting scuffing failures. By integrating the average friction coefficient from mixed lubrication models with detailed geometric and kinematic analyses from TCA and LTCA, we achieve higher accuracy in flash temperature calculations. The case study demonstrates that increasing the inclination and length of the contact path reduces the maximum flash temperature significantly, primarily due to higher contact ratios and lower loads per tooth. This insight is valuable for designing spiral bevel gears with enhanced scuffing resistance, particularly in high-performance applications. Future work could explore dynamic effects, thermal network modeling, and experimental validation to further advance the reliability of spiral bevel gear systems. As technology progresses, the demand for efficient and durable spiral bevel gears continues to grow, making such research imperative for next-generation mechanical transmissions.