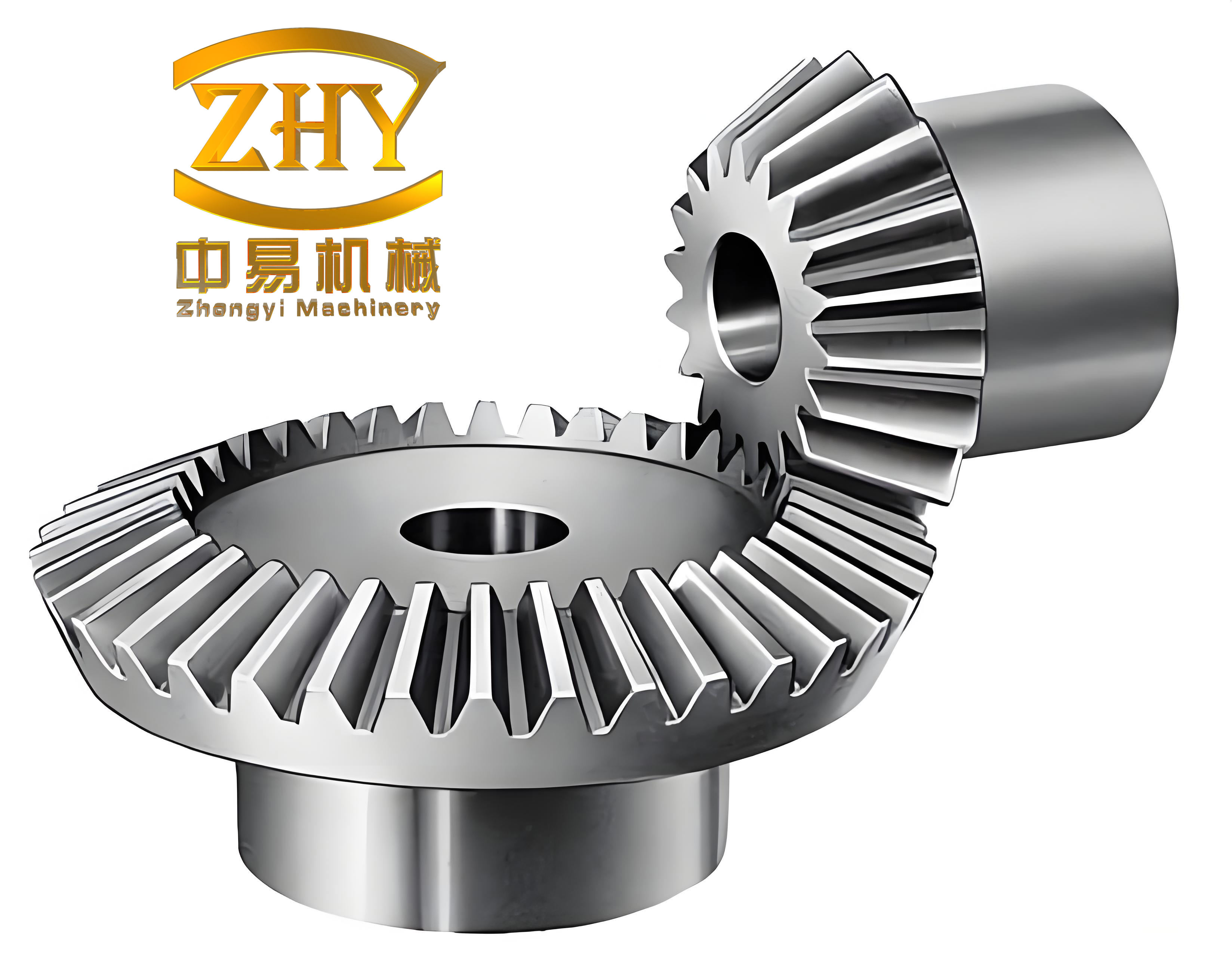

In modern high-volume manufacturing, particularly within the automotive and tractor industries, the pursuit of efficiency, precision, and cost-effectiveness is relentless. Among the various components, the straight bevel gear is a critical element in differentials and other power transmission systems. Before delving into the core research on the fundamental problems associated with the circular broaching method, it is essential to briefly review the traditional methods used for batch and mass production of these gears.

Currently, three primary methods are conventionally employed for manufacturing straight bevel gears in such settings:

| Method | Process Description | Gear Tooth Profile | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Milling & Planing (Face Milling) | Consists of two operations: roughing with formed cutters and finishing via a generating planing action. | Approximate involute, octoidal form. | Common but relatively slow; lower productivity. |

| 2. Dual-Cutter Face Hobbing | Uses large-diameter cutter heads (~400mm) with an internal conical arrangement of cutting edges to generate the teeth via a continuous indexing process. | Octoidal form (interchangeable with Milling & Planing). | Higher productivity than planing for small modules; allows crowning; higher tool cost. |

| 3. Circular Broaching (Circular Pull Broaching) | Uses a large, continuously rotating broach tool with sequentially arranged cutting teeth to pull-cut the tooth space in a single, rapid stroke. | Circular-arc form in the developed back-cone section. | Exceptionally high productivity; high precision and surface finish; complex, dedicated tooling. |

The transition from traditional methods to circular broaching represents a significant technological leap. Based on practical experience, the circular broaching method for straight bevel gears demonstrates a series of compelling advantages over the conventional milling and planing method:

- Productivity Increase: Up to 10 times higher output.

- Resource Efficiency: Drastic reduction in required production floor space, machine count (from 10+ machines to 2), and electrical power consumption (saving hundreds of thousands of kWh annually).

- Quality Improvement: Enhanced static strength of the gear, improved surface finish, and higher machining precision. For instance, the variation in mounting distance when meshed with a master gear can be controlled within $$0.05 \, \text{mm}$$ per revolution and $$0.02 \, \text{mm}$$ per tooth index, a level unattainable with the old method.

- Operational Stability: Reduced scrap rates and minimized machine adjustment needs.

It must be noted, however, that the circular broaching method has its drawbacks. The resulting straight bevel gear employs a circular-arc tooth profile, which can be slightly more sensitive to installation errors compared to the octoidal profile from generating methods. Furthermore, the complexity of coordinating the relative tool-work motion, depth feed, and profile corrections is built into the broach tool’s structure, making it intricate and costly to manufacture, often requiring dedicated tool-grinding machines.

Introduction to the Circular Broaching Process

Circular broaching for straight bevel gears was pioneered in the 1930s. This method has since become extensively adopted in high-volume industries. Despite advancements in near-net-shape processes like precision forging, circular broaching remains a highly efficient, reliable, and viable advanced manufacturing technique.

The gears produced by this method rival or even surpass generated gears in terms of meshing accuracy, smooth operation, noise level, strength, and wear resistance. The kinematics and adjustment procedures of a broaching machine are also significantly simplified compared to generating machines.

The process fundamentals are as follows: A large-diameter broach tool (up to 400 mm) rotates at a constant speed about its axis. For a straight bevel gear with a tooth depth not exceeding approximately 5 mm (equivalent to a module near 5), roughing and finishing of a tooth space can be completed in one full revolution of the tool. For deeper teeth, separate roughing and finishing cycles are used.

In the combined roughing/finishing cycle, the gear blank remains stationary (or moves linearly relative to the tool). The broach tool, while rotating, also performs a coordinated linear feed motion along the tooth space. The tool’s cutting teeth are divided into two sections: the roughing section and the finishing section. The process cycle is as follows:

- Roughing Stroke: The tool feeds slowly from the toe (small end) of the gear tooth space towards the heel (large end). The top edges of the spirally arranged roughing teeth remove the bulk of the material. The depth of cut is governed by the helical shape of these top edges.

- Transition & Semi-Finishing: Upon reaching full depth, the tool rapidly traverses further towards the heel. The final few roughing teeth (semi-finishing teeth) act during this motion.

- Finishing Stroke: The feed direction reverses at a constant speed. Now, the finishing teeth, with their concave circular-arc side cutting edges, engage to cut the final profiles of both flanks of the tooth space.

- Auxiliary Operations: A chamfering device located between the semi-finishing and finishing sections removes burrs at the large end of the tooth. A gap between the last finishing tooth and the first roughing tooth provides time for the workpiece to index to the next tooth space.

This cycle repeats continuously until all teeth of the straight bevel gear are completed, with one cycle typically taking only 3 to 4 seconds. A key characteristic is that there is no generating roll motion between the tool and the workpiece. The tooth surface is formed via an enveloping method without a fixed instantaneous center, where each finishing tooth creates a specific portion of the final flank.

Tooling for Circular Broaching

The broach tool, or “broach head,” is a masterpiece of specialized tool design. It features an assembly-based structure for manufacturability and maintenance.

- Construction: The head holds multiple precision-machined blade segments (often 6 or 8). Each segment contains 12-15 radially distributed cutting teeth. The segments are mounted onto the tool body via accurately machined cylindrical and conical reference surfaces and secured with bolts.

- Tooth Geometry: To cut both flanks of a tooth space simultaneously, each tool tooth has a bi-concave side profile. The axial section of this side cutting edge is a circular arc. Crucially, all tool teeth share the same radius of curvature $$R_t$$ for their side-cutting arcs.

- Cutter Angles: Teeth are ground with a rake face providing a top rake angle of about $$10^\circ$$ and a clearance face for a top relief angle of about $$5^\circ$$. The side relief is created via a radial backing-off grind, ensuring the cutting profile remains constant after resharpening.

- Key Design Principle: To produce a straight bevel gear whose tooth space width and profile change proportionally from heel to toe, it is not the tool tooth’s arc radius that varies, but the position of the arc’s center for each successive tooth. This brilliant simplification allows all teeth to be ground with a single grinding wheel set at different infeeds, drastically reducing tool manufacturing complexity and cost.

A typical broach head layout might include 72 total teeth: 6 segments x 12 teeth. The angular distribution allocates space for roughing, semi-finishing, finishing, chamfering, and indexing operations.

Tooth Profile Generated by Circular Broaching

The tooth profile of a straight bevel gear made by circular broaching is distinct from that of a generated gear. It is a circular-arc profile in the developed back-cone plane. This is a direct consequence of using tool teeth with a fixed circular-arc radius.

While one might initially consider using a true involute profile or a varying-radius arc on the tool to replicate a perfect generated tooth, these approaches would lead to prohibitively complex and expensive tooling. The choice of a constant-radius, shifted-center arc profile is a pragmatic and effective engineering solution.

It is vital to clarify that this is not a simple, approximate substitute for an involute curve as used in early cast gears. The circular-arc profile in modern circular broaching is derived from fundamental meshing principles, considering practical application needs. Its characteristics can be summarized as follows:

| Characteristic | Description & Implication |

|---|---|

| 1. Profile Modification (Tip/Flank Relief) | By carefully selecting the arc radius, the resulting profile deviates from a theoretical perfect involute in a controlled manner. This creates a localized contact area in the central region of the tooth height under light loads, which promotes smooth, quiet operation—effectively producing a relieved or crowned profile inherently. |

| 2. Freedom from Undercut | The circular-arc profile is not constrained by a base circle limitation. Therefore, issues like undercut at low tooth numbers are avoided. There is no need for the addendum, dedendum, or thickness corrections typically required for involute gears to prevent undercut. |

| 3. Lengthwise Crowning | By appropriately positioning the tool tooth arc centers, the process can naturally introduce a crowning effect along the tooth length. This ensures contact is localized in the center of the face width, accommodating minor misalignments and improving load distribution. |

| 4. Non-Interchangeability | A critical point is that a straight bevel gear produced by circular broaching (circular-arc profile) is not interchangeable with one produced by a generating method like planing (octoidal/involute profile). They must be used as a matched set or pair. |

The profile’s performance stems from acknowledging real-world conditions: manufacturing errors, elastic deformations under load, and the need for running-in. A mathematically perfect, full-face-contact profile is often less ideal in practice than a deliberately relieved one that ensures stable, localized contact under operating conditions.

Mathematical Foundation: Curvature Radius Calculations

The design of the circular broaching process rests on specific mathematical relationships governing the curvature of the gear tooth and the tool tooth.

1. Curvature Radius of the Gear Tooth (Back-Cone Developed Plane):

Starting from the fundamental law of gearing to ensure uniform motion transfer, the approximate radius of curvature for the circular-arc profile of the gear in its developed back-cone plane can be derived. For a pair of mating straight bevel gears, the formulas for the gear (larger member) and the pinion (smaller member) are:

For the gear:

$$ R_g = \frac{r_{vg}^2}{r_{vp} \cdot \sin \alpha} \left( 1 + \frac{r_{vp}}{r_{vg}} \right) $$

For the pinion:

$$ R_p = \frac{r_{vp}^2}{r_{vg} \cdot \sin \alpha} \left( 1 + \frac{r_{vg}}{r_{vp}} \right) $$

Where:

$$ R_g, R_p $$ = Radius of curvature of the gear and pinion tooth profile, respectively.

$$ r_{vg}, r_{vp} $$ = Pitch radius of the equivalent virtual cylindrical gear in the developed back-cone plane for the gear and pinion.

$$ \alpha $$ = Pressure angle at the mean cone distance.

It is important to note that the derivation of these formulas involves applying Taylor series expansions and neglecting higher-order terms. Therefore, these are approximate formulas. For high-speed, heavy-duty, or high-precision applications, the values obtained from these formulas require subsequent refinement and correction.

2. Theoretical Curvature Radius of the Tool Tooth (Axial Section):

A more complex relationship exists between the gear’s tooth curvature and the tool’s cutting edge curvature. Through rigorous kinematic analysis of the broaching process, the theoretical radius of curvature for the tool tooth in its axial section can be derived precisely:

$$ R_t = \frac{R \cdot r_m}{R \cdot \sin \psi \pm r_m \cdot \sin \Delta} $$

Where:

$$ R_t $$ = Theoretical radius of curvature of the broach tool tooth side cutting edge (axial section).

$$ R $$ = Radius of curvature of the straight bevel gear tooth in the developed back-cone plane (from prior calculation).

$$ \Delta $$ = Angle between the tool feed direction and the gear’s pitch line, within the tangent plane to the tooth surface along the pitch line.

$$ \psi $$ = Half of the angle between the two tangent planes to the opposing flanks of a tooth space, measured in the tool’s axial section.

$$ r_m $$ = Cutting radius at the point where the tool contacts the gear’s pitch line.

$$ r_c $$ = Equivalent pure rolling radius during the tool’s cutting motion.

The “±” sign in the denominator depends on whether the convex or concave side of the tool tooth is being considered for the respective gear flank. This formula is of paramount theoretical value for understanding the process kinematics. However, it is not used directly for final tool design. The theoretical value $$ R_t $$ obtained from this equation serves as a starting point, which must then undergo a series of practical corrections to account for tool wear, grinding geometry, and optimal performance in the machining of the straight bevel gear.

In conclusion, the circular broaching method represents a sophisticated synthesis of mechanical design, kinematic principle, and practical engineering. Its dominance in high-volume straight bevel gear production is a testament to its ability to deliver unparalleled productivity while meeting stringent quality requirements, despite the initial complexity and cost of its dedicated tooling system. The underlying mathematical models provide the essential framework for designing this efficient manufacturing process.