In my extensive experience with gear manufacturing, I have observed that heat treatment technology plays a pivotal role in enhancing the comprehensive performance and quality of gear components. As mechanical products demand higher precision and reliability, understanding the dynamics of gear heat treatment processes, analyzing their advantages and drawbacks, and exploring改进 directions are crucial. This is particularly important for minimizing heat treatment defects such as distortion, improving manufacturing accuracy, and ensuring optimal service life. In this article, I will delve into the application and development of heat treatment techniques in gear production, with a focus on mitigating heat treatment defects through innovative methods and controls.

Gears are integral components in transmission systems, directly influencing the motion accuracy, stability, and reliability of machinery. Due to manufacturing errors in gears and gearboxes, ideal pure rolling between meshing tooth surfaces is often unattainable during power transmission and speed changes. This leads to impacts, sliding friction, and cyclic alternating bending stresses, collectively causing material fatigue and wear. The primary wear mechanisms include oxidative or chemical wear from grinding and frictional heating, as well as contact fatigue resulting in pitting, cracking, and spalling. To combat these issues, gear materials must exhibit high bending and contact fatigue strength, along with a hard, wear-resistant surface and a properly distributed hardened layer. Failure to achieve these properties often stems from heat treatment defects, such as inadequate hardening or excessive residual stresses.

Based on my analysis, gear materials and heat treatment methods vary significantly depending on operational conditions. For high-speed, heavy-load, impact-prone, and high-precision gears, carburized steels subjected to carburizing, quenching, and low-temperature tempering are preferred. This process yields a surface microstructure of high-carbon tempered martensite for hardness and wear resistance, and a core of low-carbon martensite for toughness. For instance, steel 20CrMnTi after treatment achieves a surface hardness of 58–62 HRC and core hardness of 30–45 HRC. For moderate conditions, quenched and tempered steels with induction hardening are used, offering good fatigue resistance but slightly lower wear resistance. For low-speed, light-load gears, nodular cast iron with normalizing or austempering suffices. However, each method carries risks of heat treatment defects, including distortion, cracking, or soft spots, which I will explore later.

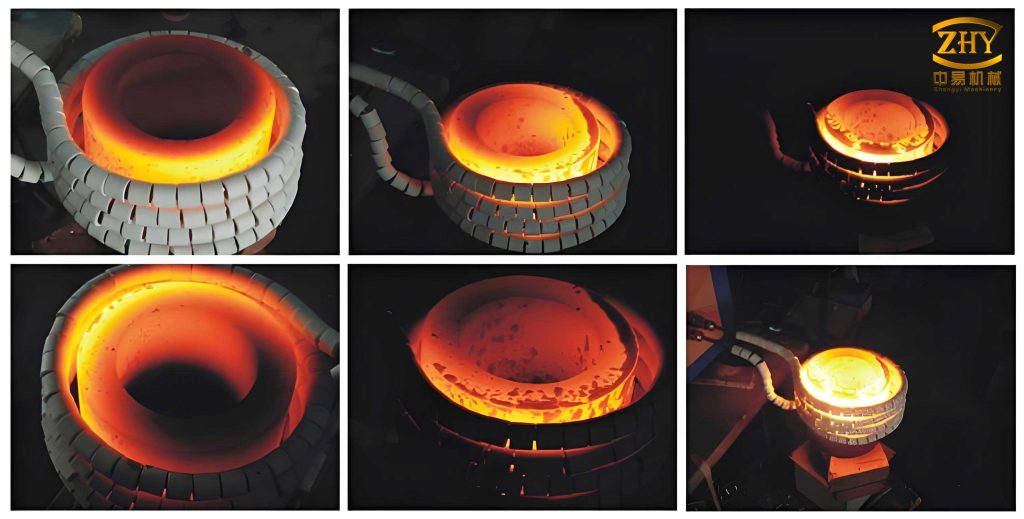

In my practice, I have found that induction heating surface hardening is widely adopted due to its rapid heating, high productivity, minimal distortion, and controllable hardened depth. It reduces surface oxidation and decarbonization, enhancing fatigue strength. Nonetheless, heat treatment defects like uneven hardening or thermal stresses can still occur if parameters are not optimized. To illustrate the relationship between heat treatment processes and material properties, I have summarized key methods in Table 1.

| Material Type | Heat Treatment Process | Typical Hardness (Surface) | Common Heat Treatment Defects | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carburized Steel (e.g., 20CrMnTi) | Carburizing + Quenching + Tempering | 58–62 HRC | Distortion, cracking, excessive residual austenite | High-speed, heavy-load gears |

| Quenched and Tempered Steel | Induction Hardening | 50–55 HRC | Soft spots, overheating, grain growth | Moderate-duty gears |

| Nodular Cast Iron | Normalizing or Austempering | 250–300 HB | Graphite degeneration, porosity issues | Low-speed, light-load gears |

The innovation in gear heat treatment processes has been driven by the need to reduce heat treatment defects and improve consistency. Traditionally, gear forgings underwent normalizing as a preparatory treatment to enhance machinability and uniformity. However, normalizing often leads to variable cooling rates, resulting in non-uniform microstructures like bainite, which adversely affects切削 performance and increases distortion during subsequent carburizing and quenching. In my work, I have advocated for isothermal annealing, which involves holding the forging at a specific temperature to achieve a more homogeneous structure. This method not only improves machinability but also stabilizes dimensional accuracy post-heat treatment, thereby mitigating heat treatment defects related to distortion.

Furthermore, cold extrusion forming has emerged as an alternative to traditional forging and machining. It eliminates heating, thus avoiding oxidation and decarbonization, and produces near-net-shape gears with minimal余量. For small-module gears, teeth can be directly extruded, reducing加工 time and costs. The continuous metal fiber flow in cold-extruded gears enhances strength and toughness. However, this requires steels with high plasticity and low deformation resistance, often achieved through spheroidizing annealing to prevent cracking—a potential heat treatment defect during cold forming. To quantify the benefits, I often use formulas to describe material behavior. For example, the stress during cold extrusion can be modeled as: $$ \sigma_{ext} = K \cdot \epsilon^n $$ where \( \sigma_{ext} \) is the flow stress, \( K \) is the strength coefficient, \( \epsilon \) is the strain, and \( n \) is the work-hardening exponent. Proper heat treatment reduces \( K \) and \( n \), minimizing defects.

One of the most critical aspects I focus on is controlling heat treatment defects, particularly distortion. Gear distortion arises from a complex interplay of factors, including furnace loading, cooling rate of quenchants, material hardenability, thermal and transformational stresses, and residual stresses from prior machining. For instance, improperly placed weight-reduction holes on gear hubs can exacerbate quenching distortion. Similarly, variations in切削 parameters across a batch lead to differential residual stresses, causing unpredictable变形. The key factors influencing distortion in carburizing and quenching are surface carbon concentration, case depth, quenching temperature, and cooling rate. These affect the expansion coefficient of the case and the resulting microstructure. Using steels with narrow hardenability bands helps control residual austenite and case depth, promoting consistent deformation and optimal residual compressive stress distribution. However, if not managed, these factors can lead to severe heat treatment defects like bore shrinkage or warping.

In my analysis, bore shrinkage in gears is primarily influenced by quenching temperature. Higher carburizing and quenching temperatures increase shrinkage, but excessively low temperatures may cause non-martensitic transformations, degrading performance. To address this, I employ techniques like martempering or austempering, which involve quenching into a medium such as salt bath or oil at an intermediate temperature, followed by cooling to room temperature. This reduces thermal gradients and minimizes heat treatment defects. The cooling process can be modeled using the Fourier heat conduction equation: $$ \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \alpha \nabla^2 T $$ where \( T \) is temperature, \( t \) is time, and \( \alpha \) is thermal diffusivity. By controlling \( \alpha \) through quenchant selection, distortion is reduced. Computer-controlled spray cooling allows precise cooling of specific part areas, offering better control over cooling rates than conventional quenchants. To elaborate on distortion factors, I have compiled Table 2.

| Factor | Effect on Heat Treatment Defects | Mitigation Strategy | Formula/Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quenching Temperature | High temperature increases distortion and shrinkage; low temperature causes soft spots | Optimize temperature based on material; use martempering | $$ \Delta D \propto \beta \cdot \Delta T $$ where \( \Delta D \) is dimensional change, \( \beta \) is thermal expansion coefficient, \( \Delta T \) is temperature drop |

| Cooling Rate | Rapid cooling induces thermal stresses; slow cooling leads to poor hardness | Use controlled quenchants (e.g., polymer solutions); implement spray cooling | Newton’s law of cooling: $$ \frac{dT}{dt} = -h(T – T_{\text{med}}) $$ where \( h \) is heat transfer coefficient |

| Material Hardenability | Wide hardenability bands cause uneven transformation, increasing distortion | Select steels with narrow hardenability; adjust case depth | Ideal case depth \( d_c \) can be estimated: $$ d_c = k \sqrt{t} $$ where \( k \) is diffusion constant, \( t \) is time |

| Residual Stresses | Machining stresses interact with heat treatment stresses, exacerbating defects | Apply stress-relief annealing before heat treatment; optimize machining parameters | Residual stress \( \sigma_{res} \) can be modeled: $$ \sigma_{res} = E (\epsilon_{thermal} + \epsilon_{transform}) $$ where \( E \) is Young’s modulus |

Throughout my career, I have emphasized that heat treatment defects are not inevitable; they can be managed through holistic approaches. This includes optimizing gear design—for example, ensuring symmetrical structures to reduce thermal gradients—and controlling process parameters. The use of advanced simulation software allows predicting distortion patterns based on finite element analysis (FEA). The distortion \( \delta \) can be expressed as a function of multiple variables: $$ \delta = f(T, C, t, \dot{Q}, \sigma_{0}) $$ where \( T \) is temperature, \( C \) is carbon concentration, \( t \) is time, \( \dot{Q} \) is cooling rate, and \( \sigma_{0} \) is initial stress. By iteratively refining these variables, heat treatment defects are minimized.

Another area of innovation is the development of low-pressure carburizing and high-pressure gas quenching, which offer better control over case uniformity and reduce distortion compared to traditional gas carburizing. These methods minimize intergranular oxidation and improve surface integrity, addressing common heat treatment defects like pitting and fatigue failure. Additionally, the integration of in-process monitoring using sensors for temperature and atmosphere composition enables real-time adjustments, further reducing defects. In my view, the future lies in adaptive heat treatment systems that use artificial intelligence to predict and correct defects dynamically.

To comprehensively assess the impact of heat treatment on gear performance, I often refer to mechanical property relationships. For instance, the contact fatigue life \( N_f \) of a gear tooth can be related to surface hardness \( H \) and residual stress \( \sigma_r \) through: $$ N_f \propto \left( \frac{H^m}{\sigma_r} \right) $$ where \( m \) is an exponent dependent on material. Heat treatment defects like soft zones reduce \( H \), drastically shortening \( N_f \). Similarly, bending fatigue strength \( \sigma_b \) is influenced by core hardness and microstructure: $$ \sigma_b = \sigma_0 + k \cdot \sqrt{d} $$ where \( \sigma_0 \) is base strength, \( k \) is a constant, and \( d \) is grain size. Proper heat treatment refines grains, enhancing \( \sigma_b \), whereas defects like overheating coarsen grains, degrading performance.

In conclusion, the application and development of heat treatment technology in gear manufacturing have significantly advanced, yet heat treatment defects remain a critical challenge. Through my analysis, I have highlighted how innovations in processes like isothermal annealing, cold extrusion, and controlled quenching can mitigate these defects. The key is a systems approach that considers material selection, design, and process control. As research shifts from importing foreign technology to自主 innovation, the continued refinement of heat treatment techniques will drive improvements in gear quality and reliability, ultimately boosting mechanical industries worldwide. By persistently addressing heat treatment defects, we can achieve gears with higher precision, longer lifespan, and better performance under demanding conditions.

To further illustrate the progression of heat treatment methods and their defect profiles, I have included Table 3, which compares traditional and advanced techniques.

| Era | Dominant Process | Typical Heat Treatment Defects | Advancements | Impact on Defect Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early 20th Century | Gas Carburizing with Oil Quenching | High distortion, cracking, oxidation | Introduction of controlled atmospheres | Moderate reduction in oxidation defects |

| Late 20th Century | Induction Hardening | Soft spots, overheating, limited case depth control | Computerized control, frequency modulation | Significant reduction in uneven hardening |

| 21st Century | Low-Pressure Carburizing + High-Pressure Gas Quenching | Minimal distortion, reduced intergranular oxidation | Precision sensors, simulation models | Major reduction in distortion and oxidation defects |

| Emerging Trends | Additive Manufacturing + In-situ Heat Treatment | Porosity, residual stress concentrations | AI-driven process optimization, tailored cooling | Potential for near-zero heat treatment defects |

Ultimately, my journey in gear manufacturing has taught me that heat treatment defects are a multifaceted problem requiring continuous learning and adaptation. By leveraging formulas, tables, and advanced technologies, we can transform challenges into opportunities for innovation, ensuring that gears meet the ever-increasing demands of modern machinery.