In the realm of aerospace manufacturing, the pursuit of precision and reliability is paramount. As an engineer deeply involved in advanced gear production, I have encountered numerous challenges where heat treatment defects can compromise the integrity of critical components. This article delves into a comprehensive case study involving a high-precision gear for the C919 aircraft’s auxiliary power unit (APU), where innovative heat treatment strategies were employed to mitigate pervasive heat treatment defects such as distortion, inadequate case depth, and hardness variations. The journey from initial trial to successful validation underscores the importance of meticulous process control and adaptive engineering in overcoming these heat treatment defects.

The gear in question, fabricated from 9310 steel (AMS6265), required a monolithic carburizing and quenching process to meet stringent specifications for both the gear teeth and the internal spline. The core challenges were multifaceted: achieving a case depth of 0.381–0.635 mm, maintaining surface hardness ≥60 HRC on the gear flanks, ≥58 HRC at the tooth roots, ≥59 HRC on the spline, and ≥57 HRC at the spline root, all while controlling distortion within tight tolerances. The inherent heat treatment defects in such thin-walled, complex geometries—like warping, ovality, and dimensional instability—posed significant risks to product quality and manufacturability. Initial trials revealed severe distortions, particularly in the internal spline and gear face, which are classic manifestations of heat treatment defects in carburized components. These defects not only affected dimensional accuracy but also led to subsequent grinding difficulties, where excessive material removal could erode the effective case depth, thereby inducing another layer of heat treatment defects related to subsurface integrity.

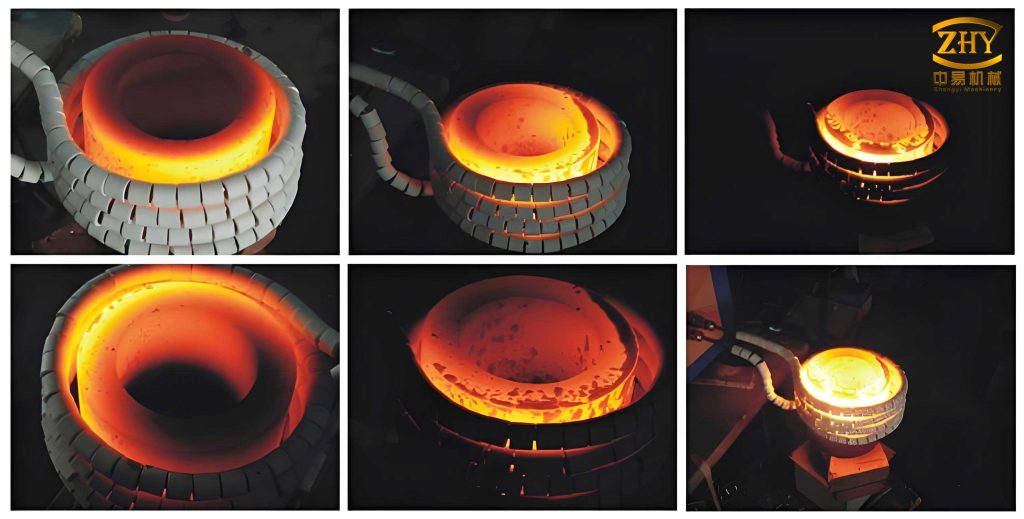

To address these heat treatment defects, a holistic process analysis was undertaken. The manufacturing sequence was refined to include stress-relief cycles and a balanced machining approach to mitigate pre-heat-treatment stresses. However, the cornerstone of overcoming heat treatment defects lay in the carburizing and quenching phases. Traditional oil quenching led to unacceptable warpage, especially in the gear’s thin web section, exacerbating heat treatment defects like face runout and spline contraction. This necessitated a shift to press quenching, a technique designed to clamp the gear faces during cooling to suppress distortion. The press quenching die incorporated a profile-matching spline mandrel to internally support the spline, countering the tendency for contraction—a common heat treatment defect in internal features. The die design ensured uniform pressure distribution, critical for minimizing residual stresses that contribute to heat treatment defects. The setup is illustrated below, showcasing how mechanical constraints can alleviate thermal-induced heat treatment defects.

Carburizing was performed using an ECM low-pressure vacuum furnace, chosen for its precise atmosphere control. To combat heat treatment defects associated with case depth inconsistency, computer simulations were employed to optimize the carburizing cycle. The relationship between carburizing time and effective case depth can be modeled using the diffusion equation, where the case depth \(d\) is proportional to the square root of time \(t\): $$d = k \sqrt{t}$$ Here, \(k\) is a constant dependent on temperature and carbon potential. For this gear, the target case depth had to account for subsequent grinding allowances; excessive grinding could lead to heat treatment defects like reduced surface hardness. Thus, the grinding stock was meticulously calculated. Based on internal standards, the allowable stock removal per side was limited to approximately 0.102 mm to prevent compromising the case. The correlation between case depth and grinding stock is summarized in Table 1, which highlights how improper allowances can exacerbate heat treatment defects.

| Quality Grade | Effective Case Depth Range (mm) | Maximum Allowable Stock Removal per Side (mm) | Risk of Heat Treatment Defects if Exceeded |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.381–0.635 | 0.102 | High: Reduced hardness, shallow case |

| 2 | 0.635–0.889 | 0.152 | Moderate: Potential for distortion |

| 3 | 0.889–1.143 | 0.203 | Low: But may increase residual stress |

In initial trials, the grinding stock was set too high, leading to heat treatment defects where the tooth roots failed to meet hardness requirements after grinding. This was due to excessive material removal, which stripped away the carburized layer. To rectify this, the hob geometry was adjusted using gear calculation software to reduce the stock allowance. The calculation for gear tooth thickness before and after grinding is critical. For instance, the maximum tooth thickness after hobbing \(S_{\text{hob}}\) and the minimum after grinding \(S_{\text{grind}}\) determine the stock per side \(\Delta S\): $$\Delta S = \frac{S_{\text{hob}} – S_{\text{grind}}}{2}$$ By ensuring \(\Delta S \leq 0.102\) mm, the risk of heat treatment defects from over-grinding was mitigated. Table 2 presents sample calculations for the gear’s dimension over pins, demonstrating how precise tolerancing can prevent heat treatment defects.

| Stage | Dimension Over Pins (mm) | Tooth Thickness (mm) | Stock per Side (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| After Hobbing | 203.20 | 2.4198 | 0.141 (initial, too high) |

| After Hob Adjustment | 203.15 | 2.3380 | 0.100 (target) |

| After Grinding | 203.05 | 2.1381 | 0.000 (final) |

Distortion monitoring was integral to managing heat treatment defects. The gear’s outer diameter and face runout were measured after carburizing and quenching to track dimensional changes. Data accumulated from multiple batches revealed a consistent pattern: post-quench contraction of approximately 0.01–0.03 mm in the outer diameter, and face runout controlled within 0.10–0.20 mm with press quenching. This data informed adjustments to the spline mandrel size; initially, an oversized mandrel exacerbated heat treatment defects by over-expanding the spline, but resizing to a slightly smaller diameter allowed for controlled contraction, eliminating gauge rejection. The effectiveness of press quenching in suppressing heat treatment defects like warpage is quantifiable. The face runout reduction can be expressed as a function of clamping pressure \(P\) and cooling rate \(C\): $$\Delta R = \alpha \cdot \frac{T_{\text{max}} – T_{\text{min}}}{\beta + \gamma P}$$ where \(\Delta R\) is the runout, \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(\gamma\) are material constants, and \(T\) are temperatures. Higher \(P\) reduces \(\Delta R\), directly addressing heat treatment defects.

The carburizing process itself was fine-tuned to avoid heat treatment defects such as excessive carbide formation at the surface, particularly in the spline area which isn’t ground post-heat-treatment. The carbon potential \(C_p\) in the furnace was regulated using a proportional-integral-derivative (PID) control model: $$C_p(t) = K_p e(t) + K_i \int_0^t e(\tau) d\tau + K_d \frac{de(t)}{dt}$$ where \(e(t)\) is the error between desired and actual carbon concentration. By maintaining \(C_p\) at an optimal level during the boost phase and extending the diffusion phase, surface carbides were minimized, reducing brittleness—a subtle but critical heat treatment defect. The final carburized layer exhibited a gradient described by the error function solution to Fick’s second law: $$C(x,t) = C_s – (C_s – C_0) \cdot \text{erf}\left(\frac{x}{2\sqrt{Dt}}\right)$$ where \(C(x,t)\) is the carbon concentration at depth \(x\) and time \(t\), \(C_s\) is the surface concentration, \(C_0\) is the initial bulk concentration, and \(D\) is the diffusion coefficient. Controlling this profile is essential to prevent heat treatment defects like soft cores or spalling.

Post-quench treatments, including cryogenic processing and tempering, were employed to further mitigate heat treatment defects. Cryogenic treatment at -80°C helped transform retained austenite to martensite, enhancing hardness stability and reducing the risk of dimensional change over time—a latent heat treatment defect. Tempering then relieved quenching stresses without significantly lowering hardness, following the Hollomon-Jaffe parameter for tempering effect: $$P = T(\log t + C)$$ where \(P\) is the tempering parameter, \(T\) is temperature in Kelvin, \(t\) is time in hours, and \(C\) is a constant. This ensured a balanced microstructure, free from heat treatment defects like excessive brittleness or softening.

Validation of the improved process was conducted through rigorous testing at an independent laboratory. The results, summarized in Table 3, confirm that the targeted specifications were met without significant heat treatment defects. The gear teeth and spline exhibited uniform hardness and case depth, with distortion within acceptable limits. This success underscores how systematic process optimization can conquer pervasive heat treatment defects in aerospace components.

| Feature | Surface Hardness (HRC) | Effective Case Depth (mm) | Core Hardness (HRC) | Observation on Heat Treatment Defects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gear Pitch Diameter | 64.0 | 0.508 | 40 | No defects: Uniform carburization |

| Gear Root | 63.0 | 0.457 | 40 | Minimal grinding effect, no soft roots |

| Internal Spline | 64.0 | 0.584 | 40 | Slight carbide aggregation, within limits |

In conclusion, the battle against heat treatment defects in high-precision aerospace gears demands a multifaceted strategy. By integrating press quenching with profile mandrels, precisely calculating grinding allowances, and optimizing carburizing cycles through diffusion models, we can effectively suppress distortions, control case depth, and maintain hardness integrity. Each of these steps directly addresses specific heat treatment defects, transforming potential failures into reliable performance. The data-driven approach, utilizing tables and mathematical formulations, provides a blueprint for replicating this success in similar applications. As heat treatment remains a cornerstone of metallurgical engineering, continuous vigilance against heat treatment defects through innovation and precise control is essential for advancing aerospace manufacturing.

Beyond this case, the principles discussed here have broader implications. For instance, the press quenching technique can be modeled more generally to predict distortion in thin-walled gears. The total distortion \(D_t\) can be expressed as a sum of thermal gradient effects and phase transformation contributions: $$D_t = \int_V \epsilon_{th}(T) dV + \sum_i \epsilon_{pt,i} \cdot f_i$$ where \(\epsilon_{th}\) is thermal strain, \(\epsilon_{pt}\) is phase transformation strain, and \(f_i\) is the volume fraction of phase i. Minimizing \(D_t\) is key to avoiding heat treatment defects. Additionally, statistical process control (SPC) charts can monitor heat treatment defects over production runs, using control limits derived from historical data. For example, the mean \(\bar{x}\) and range \(R\) of gear diameter measurements after quenching can track stability: $$\text{UCL} = \bar{x} + A_2 R, \quad \text{LCL} = \bar{x} – A_2 R$$ where \(A_2\) is a constant. This proactive detection helps nip heat treatment defects in the bud.

Furthermore, the interaction between material composition and heat treatment response cannot be overlooked. For 9310 steel, the hardenability, calculated using the ideal critical diameter \(D_I\) via Grossmann’s method, influences susceptibility to heat treatment defects: $$D_I = \sum (\% \text{alloy}) \cdot k_i$$ where \(k_i\) are multipliers for elements like Ni, Cr, Mo. Higher hardenability can reduce distortion but may increase residual stress, a trade-off that must be managed to prevent heat treatment defects. In our process, the balance was struck by optimizing the quench medium’s cooling severity, quantified by the H-value in the quenching intensity equation: $$v = H \cdot (T_s – T_q)$$ where \(v\) is cooling rate, \(T_s\) is surface temperature, and \(T_q\) is quenchant temperature. A moderate H-value ensured sufficient hardening without exacerbating heat treatment defects like cracking.

In retrospect, the journey from initial failure to final success was paved with insights into heat treatment defects. Each iteration refined our understanding, whether it was adjusting the spline mandrel dimensions based on shrinkage data or tweaking carburizing times via simulation. The tables and formulas presented herein serve as a testament to the engineering rigor required to conquer these defects. As we look to future projects, such as gears for even more demanding applications, the lessons learned will continue to inform our strategies to mitigate heat treatment defects, ensuring that every component meets the sky-high standards of aerospace excellence.