The gear is a fundamental and critical transmission component within the modern automobile. Its performance is paramount, directly influencing vehicle safety through reliable power transfer and driver comfort via noise, vibration, and harshness (NVH) characteristics. The journey from a steel billet to a precision gear is complex, involving numerous manufacturing steps where both the inherent quality of the steel and the applied thermal processing play decisive roles. In this analysis, I will delve into the intricate relationship between gear steel metallurgy and heat treatment practices, examining how they collectively govern the final gear’s mechanical properties, dimensional accuracy, and long-term durability. A profound understanding of these interactions is essential for mitigating prevalent heat treatment defects and achieving the high performance demanded by today’s automotive industry.

The operational environment for automotive gears is exceptionally demanding. They are subjected to complex loading conditions, including high-cycle contact stresses, bending fatigue, and occasional impact loads. Consequently, the gear material must exhibit a synergistic blend of high surface hardness for wear and contact fatigue resistance, a tough core to withstand bending stresses and shocks, and excellent dimensional stability through heat treatment to maintain precise tooth geometry. Failure in any of these aspects can lead to premature pitting, tooth breakage, or unacceptable noise, underscoring the necessity for meticulous control over both material selection and processing. The core objective is to engineer a component with a hard, wear-resistant case and a ductile, strong core—a dichotomy masterfully achieved through alloy design and controlled thermal cycles, always with an eye on avoiding detrimental heat treatment defects.

I. The Foundational Role of Gear Steel Metallurgy

The selection and quality of the base steel set the ceiling for potential gear performance. It is not merely about chemical composition but about the consistency and uniformity of its internal structure. Key metallurgical factors act as pre-determinants for how the steel will respond to subsequent forging, machining, and, most critically, heat treatment.

1.1 Hardenability: The Core Determinant of Properties and Distortion

Hardenability, defined as the depth to which a steel will transform to martensite upon quenching from the austenitizing temperature, is arguably the most critical property of a gear steel. It dictates the core hardness after quenching, which is directly linked to bending fatigue strength and tooth root load capacity. An optimal core hardness, typically in the range of 35-42 HRC, provides the ideal balance of strength and toughness. Significantly, hardenability is not a single value but a curve (often characterized by Jominy end-quench test values like J9 and J15<!–), and its *bandwidth* is equally crucial. A narrow hardenability band ensures consistent response to heat treatment across different batches, which is vital for predictable dimensional change. Wide fluctuations in hardenability lead to erratic and unpredictable gear distortion, a major category of heat treatment defects that increases scrap rates and compromises assembly precision. Modern steelmaking employs ladle metallurgy and precise composition control to deliver “H”-grade steels with guaranteed hardenability bands.

| Manufacturer | Target Core Hardness Range (HRC) |

|---|---|

| European Manufacturer A | 36.5 |

| European Manufacturer B | 32 – 42 |

| Asian Manufacturer C | ~45 |

| European Manufacturer D | 33.5 – 40 |

| North American Manufacturer E | 32 – 40 |

1.2 Steel Cleanliness: The Quest for Purity

The presence of non-metallic inclusions—oxides, sulfides, silicates—acts as stress concentrators and potential initiation sites for fatigue cracks. Total oxygen content is a key indicator of steel cleanliness. The relationship between oxide inclusion content and fatigue life is profound. Research has shown that reducing the oxygen content from 25 ppm to 11 ppm can more than double the contact fatigue strength. Furthermore, cleaner steel improves machinability by reducing tool wear. Advanced secondary refining processes like vacuum degassing and ladle furnace treatment are standard for producing high-quality gear steels, with leading specifications demanding oxygen contents below 15-20 ppm. The pursuit of ultra-clean steel is a direct effort to eliminate intrinsic material flaws that can exacerbate service failures, often unmasked during heat treatment or under load.

1.3 Grain Size and Its Stabilization

Austenitic grain size prior to and after carburizing significantly impacts mechanical properties. Coarse grains lead to coarse martensite upon quenching, reducing toughness and fatigue resistance. More critically, for carburized gears which endure prolonged exposure (8-10 hours) at high temperatures (e.g., 930°C), resistance to austenite grain growth is essential. Aluminum is a traditional grain refiner through the formation of AlN precipitates that pin grain boundaries. However, Al-killed steels can be prone to “mixed grain” structure (a heat treatment defect) after carburizing and exhibit clusters of hard, abrasive Al2O3 inclusions. Modern approaches often utilize microalloying elements like Titanium (Ti), Niobium (Nb), and Vanadium (V). These form very stable carbonitrides (e.g., TiN, Nb(C,N)) that effectively suppress grain growth even at elevated carburizing temperatures, allowing for process intensification. The Hall-Petch relationship succinctly describes the benefit of grain refinement:

$$ \sigma_y = \sigma_0 + k_y d^{-1/2} $$

where $\sigma_y$ is the yield strength, $\sigma_0$ and $k_y$ are material constants, and $d$ is the average grain diameter. Finer grains ($d↓$) lead to higher strength ($\sigma_y↑$) and improved toughness.

1.4 Banding and Microstructural Uniformity

Chemical segregation during solidification can manifest as banded structures—alternating layers of ferrite and pearlite in the hot-rolled condition. Severe banding leads to anisotropic properties, non-uniform hardness after heat treatment, and can contribute to distortion. It is considered a precursor condition that amplifies other heat treatment defects. Control involves minimizing macro-segregation through continuous casting practices and employing sufficient soaking and forging reduction to homogenize the structure. Specifications typically limit banding severity to a maximum of level 3.

1.5 The Strategic Role of Alloying Elements

The chemical composition is the blueprint for performance. Each element plays a specific role, and their interactions define the steel’s hardenability, microstructural evolution, and susceptibility to processing issues.

| Element | Primary Function | Influence on Heat Treatment & Potential Defects |

|---|---|---|

| C | Base hardenability; core strength. | Controls martensite hardness. High surface C after carburizing can lead to brittle carbides. |

| Mn | Hardenability; combines with S. | Excessive Mn can promote residual austenite and increase oxidation tendency. |

| Cr | Hardenability; carbide former. | Improves tempering resistance. Prone to oxidation at grain boundaries during gas carburizing. |

| Mo | Hardenability (potent); reduces temper embrittlement. | Enhances high-temperature strength; less prone to oxidation than Cr or Si. |

| Ni | Toughness; hardenability. | Improves core toughness; very resistant to oxidation. |

| Si | Solid solution strengthening; deoxidizer. | Strongly promotes grain boundary oxidation (a major heat treatment defect); can increase decarburization risk. |

| S | Improves machinability (forms MnS). | Generally neutral to heat treatment but can affect transverse properties if sulfide shape is unfavorable. |

| Ti, Nb, V | Grain refinement (carbonitride formers). | Suppress grain growth during carburizing, enabling higher-temperature processes and reducing distortion. |

Sulfur and Machinability: While often viewed as an impurity, sulfur (typically 0.020-0.035%) is intentionally added to improve machinability. The soft, elongated MnS inclusions act as internal chip breakers, reducing cutting forces and tool wear, which is crucial for the high-volume production of gears. The morphology control of sulfides (towards more globular shapes) is an area of development to balance machinability with ductility.

The Challenge of Internal Oxidation: During conventional gas carburizing, oxygen-bearing species in the atmosphere (CO2, H2O) can oxidize alloying elements with high oxygen affinity—primarily Si, Mn, and Cr—at the austenite grain boundaries beneath the surface. This phenomenon, known as Internal Oxidation or Intergranular Oxidation (IGO), creates a sub-surface layer of oxide particles and depleted alloy content. This layer has lower hardenability, often transforming to non-martensitic products (like troostite or bainite) upon quenching, visible as a dark etching “black network” under the microscope. This constitutes a significant heat treatment defect as it dramatically reduces surface contact fatigue strength. The depth of IGO ($\delta$) can be modeled by a parabolic growth law:

$$ \delta = k_p \sqrt{t} $$

where $k_p$ is a temperature-dependent oxidation rate constant and $t$ is time. The constant $k_p$ is highly sensitive to the steel’s composition. Strategies to combat IGO include:

- Alloy Design: Reducing elements with high oxidation potential (especially Si) and increasing resistant elements like Ni and Mo. “Si-free” or low-Si gear steels are developed for this purpose.

- Process Innovation: Using vacuum carburizing or plasma carburizing, where the oxygen potential is extremely low, effectively eliminating this heat treatment defect.

Microalloying with Nb and V: Beyond grain refinement, the addition of Nb and V enables the development of “high-temperature carburizing” steels. These steels can be carburized at 1000°C or higher without grain coarsening, significantly reducing cycle times. The fine carbonitrides also contribute to precipitation strengthening in the core after quenching and tempering. The effectiveness of a microalloy like Nb in suppressing grain growth is related to the Zener pinning force exerted by its precipitates.

II. The Transformative Power of Heat Treatment Processes

Heat treatment is the transformative stage where the potential locked within the steel chemistry is unlocked to achieve the desired gear performance. Each thermal operation must be meticulously controlled to develop the target microstructure while minimizing introduced stresses and distortions—the ever-present specter of heat treatment defects.

2.1 Forging and Preliminary Heat Treatment: Setting the Stage

Gears are typically hot-forged to shape. The as-forged microstructure is often non-uniform, with varying grain size and a Widmanstätten or mixed ferrite-pearlite structure. A preliminary heat treatment, most commonly normalizing or isothermal annealing, is therefore essential.

- Conventional Normalizing: Involves austenitizing followed by air cooling. It is simple but can lead to inconsistent hardness and microstructure due to variable cooling rates in still air, especially with part stacking. This inconsistency is a root cause of unpredictable machining behavior and subsequent heat treatment distortion.

- Isothermal Annealing (or Controlled Normalizing): A superior process where the forged parts are austenitized, then rapidly cooled to a specific temperature (e.g., 600-650°C) in a forced-air or fluidized bed, and held isothermally to produce a uniform, fine ferrite-pearlite structure. This results in a very consistent and optimal hardness (typically 160-190 HB) for machining and creates a homogeneous starting condition that greatly enhances the predictability of final hardening. Neglecting this step properly is a common source of downstream heat treatment defects related to distortion.

2.2 Case Hardening: Carburizing and Carbonitriding

This is the core process for developing the hard, wear-resistant surface. The goal is to diffuse carbon (and sometimes nitrogen) into the surface layer to a specified depth (Case Depth) and concentration profile.

Process Parameters & Controlled Outcomes:

The key variables are temperature ($T$), time ($t$), and atmosphere carbon potential ($C_p$). The case depth (CD) follows a diffusion-controlled relationship:

$$ CD = k \sqrt{t} $$

where the diffusion coefficient $k$ is exponentially dependent on temperature: $k \propto e^{-Q/RT}$, with $Q$ being the activation energy for carbon diffusion, $R$ the gas constant, and $T$ the absolute temperature. Higher temperatures drastically reduce process time but increase the risk of grain growth and distortion.

The surface carbon concentration is critical. An optimal range (0.7-0.9% C) ensures a high martensite hardness without forming massive, brittle grain-boundary carbides, which are severe heat treatment defects that act as crack initiation sites. The carbon gradient from surface to core influences the residual stress profile; a well-designed gradient induces beneficial compressive stresses at the surface.

Technology Evolution:

– Atmosphere (Gas) Carburizing: The most common method. Requires precise control of $C_p$ via gas composition (e.g., endothermic gas + natural gas) to avoid sooting (if $C_p$ too high) or decarburization (if $C_p$ too low). Internal oxidation is its main inherent heat treatment defect.

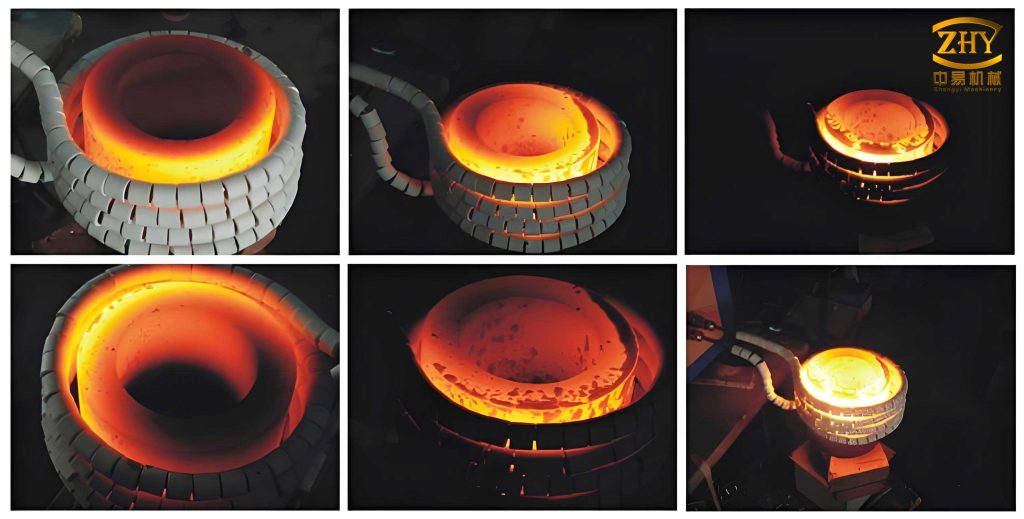

– Vacuum/Low-Pressure Carburizing: Conducted in a partial pressure of hydrocarbon gas (e.g., C2H2, C3H8). Eliminates internal oxidation, allows higher temperatures for faster processing, and provides a very clean, bright surface. It is superior for controlling heat treatment defects related to surface chemistry.

– Plasma (Ion) Carburizing: Uses a glow discharge in a hydrocarbon atmosphere. Offers very fast, clean, and precise case development with minimal distortion.

2.3 Quenching and Tempering: The Final Transformation

After carburizing, the gear is quenched to transform the high-carbon case to high-hardness martensite and the lower-carbon core to a strong, tough martensitic/bainitic structure.

Quenching Media and Distortion: The choice of quenchant (oil, polymer, high-pressure gas) is a critical compromise between achieving the required cooling rate for full hardness and minimizing thermal and transformational stresses that cause distortion and cracking—catastrophic heat treatment defects. Intensive quenching, martempering, and high-pressure gas quenching (in vacuum furnaces) are advanced techniques designed to reduce distortion.

Tempering: A mandatory follow-up to quenching, typically between 150-200°C. It relieves internal stresses, improves toughness, and stabilizes the microstructure. The tempering response can be approximated by the Hollomon-Jaffe parameter for time-temperature equivalence:

$$ P = T (C + \log t) $$

where $T$ is temperature in Kelvin, $t$ is time in hours, and $C$ is a constant. Under-tempering can leave the gear brittle, while over-tempering excessively reduces surface hardness.

2.4 Common Heat Treatment Defects and Their Origins

A systematic view of potential failures during thermal processing is essential for quality control.

| Defect Category | Description & Manifestation | Primary Causes | Preventive/Corrective Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distortion (Dimensional Change) | Unwanted changes in gear geometry (tooth profile, pitch, helix angle). Increases noise, reduces load capacity. | Non-uniform heating/cooling; residual forging stresses; inconsistent steel hardenability; improper fixturing. | Use isothermal annealing; ensure narrow hardenability band; optimize furnace loading; use press quenching or controlled quenchants. |

| Cracking (Quench Cracks) | Macroscopic cracks, often originating at stress concentrators (sharp corners, keyways). | Excessive thermal gradients during quenching; too high martensite start (Ms) temperature in case; delayed quenching. | Design with generous fillets; use milder quenchants; implement martempering; ensure immediate and uniform quenching. |

| Soft Spots / Low Hardness | Localized areas with lower-than-specified hardness in case or core. | Insufficient quenching (poor agitation, low quenchant temperature); surface decarburization during processing; inadequate carburizing. | Maintain quenchant quality and agitation; control furnace atmosphere; verify carburizing parameters and case depth. |

| Excessive Residual Austenite | Retained non-martensitic phase in the case, reducing hardness and promoting dimensional instability. | Surface carbon content too high; quenching temperature too low; inadequate quenching speed. | Control surface carbon potential; ensure proper austenitizing temperature; use deep freezing (cryogenic treatment) after quenching. |

| Internal (Intergranular) Oxidation | Dark etching subsurface network, leading to soft spots and reduced fatigue life. | Oxidation of Si, Mn, Cr by H2O/CO2 in gas carburizing atmosphere. | Use low-Si steel grades; employ vacuum or plasma carburizing; optimize gas atmosphere purity and dew point. |

| Grain Boundary Carbides | Continuous or semi-continuous brittle carbide films along prior austenite grain boundaries. | Excessively high surface carbon potential during carburizing, especially in alloy-rich steels. | Careful control of boost-diffuse cycles in carburizing; avoid excessive “boost” carbon potential. |

| Abnormal Grain Growth | Localized areas of extremely coarse grains within a fine-grained matrix. | Insufficient grain-growth inhibiting precipitates (AlN, TiN, NbC); excessive time/temperature during carburizing. | Use fine-grained steel with microalloying additions (Ti, Nb); control carburizing temperature relative to steel’s grain coarsening temperature. |

III. Future Perspectives and Integrated Approach

The advancement of automotive gear technology necessitates a fully integrated approach from steelmaking to final finishing. Steel producers must evolve beyond being mere material suppliers to becoming solutions partners. This involves:

- Predictive Metallurgy: Using computational models based on robust databases to predict hardenability, distortion, and microstructure with high accuracy, moving beyond traditional end-quench testing.

- Tailored Steel Grades: Developing next-generation steels, such as ultra-clean, low-Si grades for gas carburizing, or Nb/V-microalloyed grades for high-temperature vacuum carburizing, specifically designed to mitigate known heat treatment defects.

- Surface and Inclusion Engineering: Controlling the morphology of sulfides for optimal machinability and the complete elimination of harmful oxide clusters.

Conversely, gear manufacturers must embrace digitalization and advanced process control:

- Process Simulation: Using Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to simulate heat treatment, predicting distortion and residual stress patterns to optimize fixturing and quenching strategies before physical trials.

- Industry 4.0 Integration: Implementing real-time monitoring and adaptive control of heat treatment furnaces (temperature, atmosphere, quenchant flow) using IoT sensors and AI algorithms to ensure repeatability and detect process drift.

- Holistic Quality Management: Understanding that the quality of the preliminary forging heat treatment is as critical as the final hardening. Investing in controlled cooling lines and isothermal annealing facilities is essential for consistency.

The synergy between consistently high-quality steel and precisely controlled, often innovative, heat treatment processes is the definitive path to manufacturing high-performance automotive gears. The continuous battle against heat treatment defects—whether they originate from material inconsistencies like wide hardenability bands or from process instabilities like atmosphere fluctuations—drives progress in this field. By deepening the collaboration between metallurgists and thermal process engineers, the industry can achieve the dual goals of enhanced gear reliability and manufacturing efficiency, paving the way for the next generation of quieter, safer, and more durable vehicles.