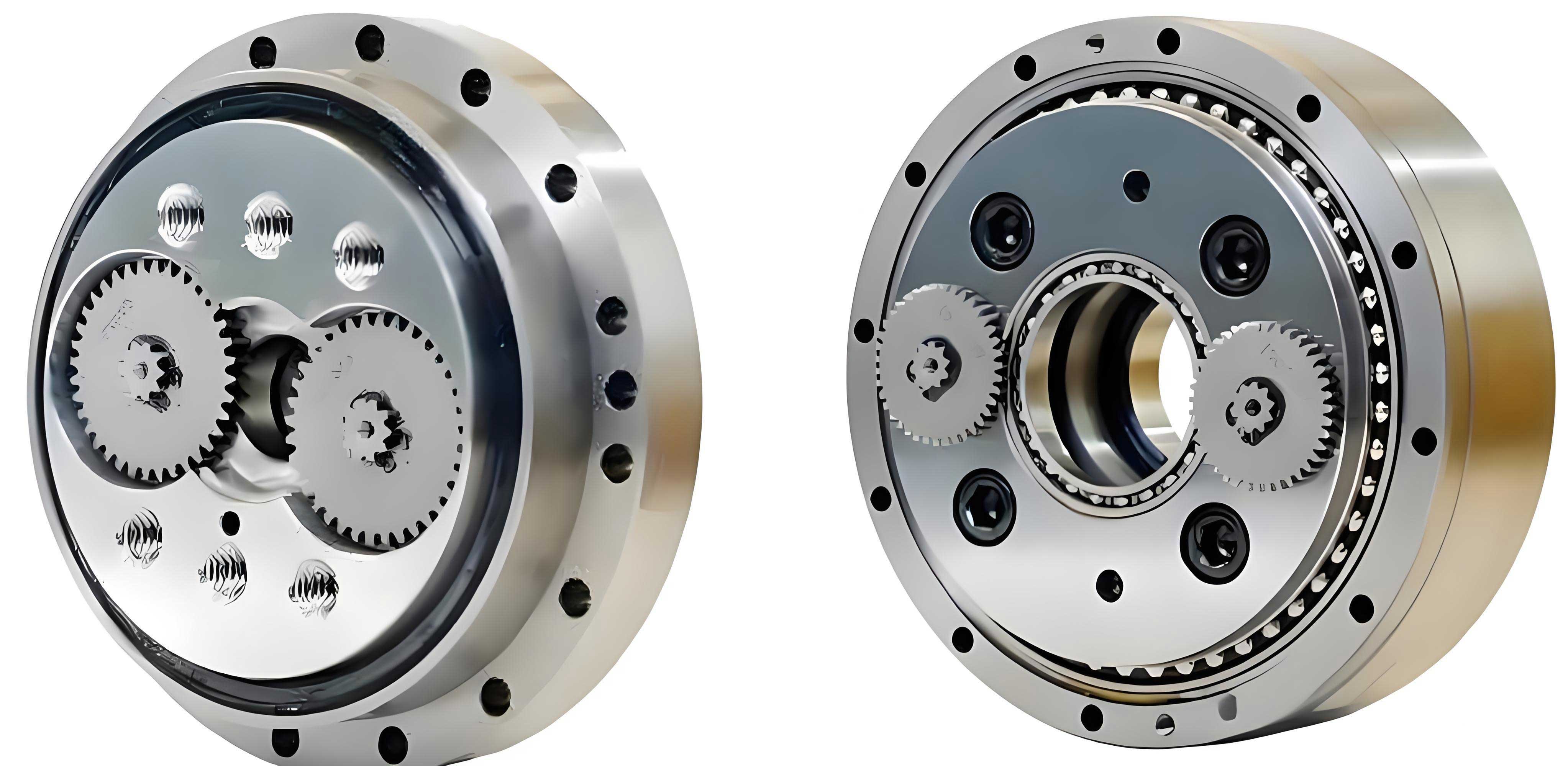

As a core component in high-end robotic and precision equipment, the performance of the Rotate Vector (RV) reducer directly dictates the overall functionality and reliability of the entire system. Ensuring its long-term, stable service under demanding conditions necessitates accurate dynamic analysis. Traditional dynamic modeling approaches for the RV reducer often rely on deterministic parameters, overlooking the significant influence of multi-source uncertainties stemming from manufacturing tolerances, assembly errors, material property variations, and fluctuating operational environments. These oversights lead to discrepancies between theoretical models and real-world behavior, consequently compromising the precision of subsequent analysis, such as vibration prediction, noise assessment, and reliability evaluation. Therefore, developing a robust methodology to quantify these uncertainties, refine the dynamic model, and reliably predict dynamic responses is paramount for advancing RV reducer design and performance assurance.

This work presents a comprehensive hierarchical Bayesian inference framework to address these challenges. We begin by establishing the dynamic theoretical models for key components of the RV reducer, specifically the crank shaft and the cycloid wheel, which are often identified as critical or weak links in the transmission chain. The governing equations of motion consider three degrees of freedom per component: two translational and one torsional. For an RV reducer system component q (representing either the crank-shaft assembly or the cycloid wheel), the dynamic equation is expressed as:

$$

\mathbf{M}_q \ddot{\mathbf{X}}_q + \mathbf{C}_q \dot{\mathbf{X}}_q + \mathbf{K}_q \mathbf{X}_q = \mathbf{F}_q

$$

where \(\mathbf{M}_q\), \(\mathbf{C}_q\), and \(\mathbf{K}_q\) are the mass, damping, and stiffness matrices, respectively. \(\mathbf{X}_q = [x_q, y_q, \theta_q]^T\) is the displacement vector containing translational displacements \(x_q\), \(y_q\) and torsional displacement \(\theta_q\). \(\mathbf{F}_q\) represents the external excitation force vector. The specific forms of these matrices differ for the crank shaft and cycloid wheel due to their distinct kinematics and loading conditions. The Newmark-β method is employed for the numerical integration of these equations to obtain displacement, velocity, and acceleration responses over time.

To account for parameter uncertainties, we define a set of dimensionless scaling parameters \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) to modify the nominal stiffness values in the theoretical model. For a given component, this parameter vector is defined as:

$$

\boldsymbol{\theta} = [\theta_1, \theta_2, \theta_3]^T

$$

where \(\theta_1, \theta_2\) typically scale the translational or mesh stiffnesses, and \(\theta_3\) scales the torsional stiffness. The true, unknown stiffness matrix \(\mathbf{K}_{q, true}\) is related to the nominal matrix \(\mathbf{K}_{q, nom}\) by these scaling factors integrated into its structure. The objective of model updating is to identify the probabilistic descriptions of these \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) parameters based on measured data.

The core of our methodology lies in the Hierarchical Bayesian Modeling (HBM) framework. Conventional Bayesian modeling struggles to properly quantify parameter uncertainty when multiple datasets from different environmental or operational conditions are available, often artificially inflating the prediction error. The HBM framework overcomes this by introducing hyperparameters. We assume that the scaling parameter vector \(\boldsymbol{\theta}^{(i)}\) for the \(i\)-th test condition (dataset \(\mathcal{D}_i\)) is drawn from a common population distribution governed by hyperparameters \(\boldsymbol{\phi}\). A typical choice is a multivariate normal distribution:

$$

\boldsymbol{\theta}^{(i)} | \boldsymbol{\phi} \sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{\mu}_{\theta}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{\theta}), \quad \boldsymbol{\phi} = \{\boldsymbol{\mu}_{\theta}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{\theta}\}

$$

Here, \(\boldsymbol{\mu}_{\theta}\) is the mean vector and \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{\theta}\) is the covariance matrix of the population distribution, representing the inter-dataset variability of the RV reducer’s parameters. For a single dataset \(\mathcal{D}_i\) containing measured responses \(\mathbf{y}\), the likelihood function, which quantifies the probability of observing the data given the parameters, is constructed. We model the discrepancy between the measured response \(\mathbf{y}\) and the model prediction \(\mathbf{g}(\boldsymbol{\theta})\) as an independent and identically distributed Gaussian error \(\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}\):

$$

\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{g}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) + \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}, \quad \boldsymbol{\varepsilon} \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \sigma_e^2 \mathbf{I})

$$

where \(\sigma_e\) is the prediction error parameter. The likelihood is therefore:

$$

p(\mathcal{D}_i | \boldsymbol{\theta}, \sigma_e) \propto (\sigma_e^2)^{-N/2} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma_e^2} J(\boldsymbol{\theta})\right)

$$

with \(J(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = [\mathbf{y} – \mathbf{g}(\boldsymbol{\theta})]^T [\mathbf{y} – \mathbf{g}(\boldsymbol{\theta})]\) and \(N\) being the number of data points. Using Bayes’ theorem, the posterior distribution for the parameters of a single dataset is:

$$

p(\boldsymbol{\theta}, \sigma_e | \mathcal{D}_i) \propto p(\mathcal{D}_i | \boldsymbol{\theta}, \sigma_e) p(\boldsymbol{\theta}) p(\sigma_e)

$$

where \(p(\boldsymbol{\theta})\) and \(p(\sigma_e)\) are prior distributions. The Transitional Markov Chain Monte Carlo (TMCMC) algorithm is used to sample from this complex posterior distribution.

The hierarchical step integrates information from all \(N_D\) available datasets. The joint posterior distribution of the hyperparameters \(\boldsymbol{\phi}\), given the complete data \(\mathcal{D} = \{\mathcal{D}_1, …, \mathcal{D}_{N_D}\}\), is:

$$

p(\boldsymbol{\phi} | \mathcal{D}) \propto p(\boldsymbol{\phi}) \prod_{i=1}^{N_D} \int p(\mathcal{D}_i | \boldsymbol{\theta}^{(i)}) p(\boldsymbol{\theta}^{(i)} | \boldsymbol{\phi}) d\boldsymbol{\theta}^{(i)}

$$

This integral is efficiently approximated using Monte Carlo integration with samples from the single-dataset posteriors. Sampling from \(p(\boldsymbol{\phi} | \mathcal{D})\) via TMCMC provides a robust quantification of the population-level uncertainty in the RV reducer’s parameters. The final, updated distribution for a parameter in a new, similar condition is given by the conditional \(p(\boldsymbol{\theta}^{new} | \boldsymbol{\phi}, \mathcal{D})\), effectively refining the dynamic model.

With the quantified parameter uncertainties (the posterior distributions of \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) and \(\sigma_e\)), we can perform dynamic response prediction for the RV reducer under new inputs. The predictive distribution for a response \(\mathbf{y}_{pred}\) accounts for both parameter uncertainty and prediction error. It can be approximated by Monte Carlo simulation:

$$

p(\mathbf{y}_{pred} | \mathcal{D}) \approx \frac{1}{M} \sum_{m=1}^{M} p(\mathbf{y}_{pred} | \boldsymbol{\theta}^{(m)}, \sigma_e^{(m)})

$$

where \(\{\boldsymbol{\theta}^{(m)}, \sigma_e^{(m)}\}\) are samples drawn from their joint posterior distribution \(p(\boldsymbol{\theta}, \sigma_e | \mathcal{D})\). This yields not just a point prediction but a full probabilistic forecast, including credible intervals.

We demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed framework using an RV-20E type reducer, focusing on its crank shaft and cycloid wheel. The nominal parameters for the dynamic models are listed below.

| Component | Mass (kg) | Moment of Inertia (kg·m²) | Translational Stiffness (N/m) | Torsional Stiffness (N·m/rad) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crank Shaft | 0.135 | 1.30e-5 | 9.84e8 | 6.00e5 |

| Cycloid Wheel | 0.305 | 4.62e-4 | 1.50e9 (Mesh) | 2.10e7 |

To simulate realistic multi-condition data, we generated \(N_D=20\) synthetic datasets. The “true” scaling parameters \(\boldsymbol{\theta}^{(i)}\) for each dataset were sampled from a population distribution: \(\boldsymbol{\theta} \sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{\mu}_{\theta, true}=[1,1,1]^T, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{\theta, true}=diag(0.05^2, 0.05^2, 0.05^2))\). Measured data \(\mathcal{D}_i\) were created by adding Gaussian noise to the simulated model outputs based on these sampled parameters.

The HBM framework was applied to this data. For comparison, a Conventional Bayesian Model (CBM) was also implemented, which treats all datasets as informing a single set of parameters without the hierarchical structure. The results for the posterior estimates of the hyper-means \(\boldsymbol{\mu}_{\theta}\) and the prediction error parameter \(\sigma_e\) are summarized below. The HBM accurately recovers the true population mean and variance, while the CBM severely underestimates the parameter variance, misattributing it to an inflated prediction error.

| Method | Parameter | Mean (\(\mu_{\theta1}\)) | Std. Dev. | Mean (\(\mu_{\theta2}\)) | Std. Dev. | Mean (\(\mu_{\theta3}\)) | Std. Dev. | Mean (\(\sigma_e\)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True Value | – | 1.000 | 0.050 | 1.000 | 0.050 | 1.000 | 0.050 | – |

| CBM | Crank Shaft | 0.993 | 0.001 | 0.986 | 0.001 | 1.006 | 0.001 | 0.0520 |

| HBM | Crank Shaft | 0.989 | 0.060 | 0.985 | 0.057 | 1.003 | 0.051 | 0.0275 |

| CBM | Cycloid Wheel | 1.002 | 0.001 | 0.981 | 0.001 | 0.990 | 0.001 | 0.0515 |

| HBM | Cycloid Wheel | 0.999 | 0.047 | 0.979 | 0.047 | 0.991 | 0.066 | 0.0197 |

The dynamic response prediction capability is validated by forecasting the torsional displacement of both components. The following figures conceptually illustrate the superiority of the HBM framework. When predicting responses, the HBM provides realistic, well-calibrated uncertainty bounds (e.g., 95% credible intervals) that fully encapsulate the synthetic “true” response. In contrast, the CBM produces either excessively narrow bounds that fail to contain the true response (when ignoring prediction error) or excessively wide, conservative bounds (when including the inflated error), both of which are less informative for practical engineering assessment.

In conclusion, this study successfully develops and applies a hierarchical Bayesian inference framework for the uncertainty quantification, model updating, and dynamic response prediction of RV reducers. The key advantage of this method is its ability to properly distinguish and quantify the inherent randomness in RV reducer parameters across multiple operational conditions from the model prediction error. By doing so, it provides a more accurate and reliable probabilistic description of the RV reducer’s dynamic properties. The updated model and the predictive distributions for critical responses offer a solid foundation for advanced RV reducer design, precision health monitoring, and robust reliability analysis, ultimately contributing to enhanced performance and longevity of the systems that rely on them.