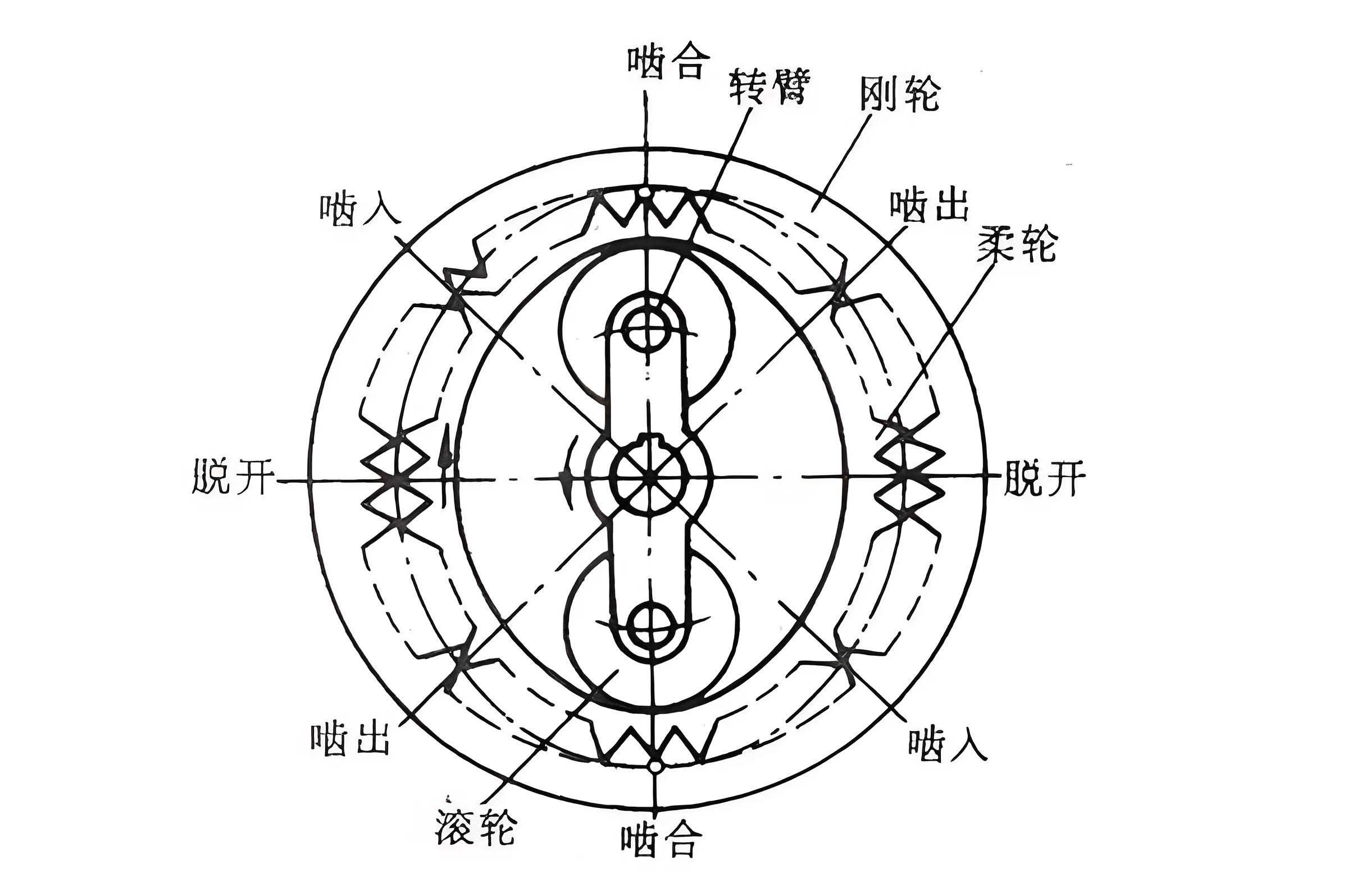

The pursuit of miniaturization, high reduction ratios, and exceptional positional accuracy in modern precision drives has firmly established the strain wave gear, also known as the harmonic drive, as a critical component. Its unique advantages make it indispensable in fields ranging from aerospace robotics to advanced industrial automation. The core of this precision transmission system comprises three elements: the circular spline (rigid ring), the flexspline (thin-walled elastic cup), and the wave generator. The flexspline, a key component, is typically manufactured as a large-modification cylindrical gear. In many standard strain wave gear designs, the flexspline features a significant positive addendum modification coefficient, often around 3. This large modification is essential for achieving a near-zero backlash meshing condition and optimal load distribution between the flexspline and circular spline teeth under the deflection induced by the wave generator.

However, the very feature that enables its superior performance—the large modification—also introduces significant challenges in its manufacturing, particularly during the hobbing process, which is the primary method for generating the teeth. Using a standard involute gear hob to cut a gear with such a large modification coefficient can lead to substantial theoretical machining errors on the tooth flanks. These errors, if not properly understood and mitigated, directly compromise the transmission accuracy, load capacity, and smoothness of the final strain wave gear assembly. Therefore, a deep understanding of the hobbing formation mechanism for large-modified gears and precise control over the resulting tooth surface errors is paramount for producing high-performance strain wave gear drives. This analysis focuses on establishing a comprehensive numerical simulation model to investigate this mechanism, quantify the inherent theoretical machining errors, and provide actionable guidance for optimizing hob geometry and process parameters to achieve the necessary precision for strain wave gear applications.

Mathematical Modeling for Hobbing Simulation and Error Evaluation

To accurately simulate the hobbing process and predict the theoretical form of the machined tooth surface, a precise mathematical model encapsulating the hob geometry, the machine kinematics, and the workpiece is essential.

Parametric Model of the Hob Cutting Edges

The foundation of the simulation lies in defining the geometry of the hob. We consider a standard single-start, left-handed Archimedes hob. The axial tooth profile of the hob serves as the generator for all its cutting edges. A local coordinate system $$O_1 – X_1Y_1$$ is fixed to the hob, with the $$X_1$$-axis aligned with the hob axis and the $$Y_1$$-axis bisecting the axial tooth profile. The profile, parameterized by variable $$s$$ along the $$X_1$$-axis, is defined as:

$$

P_1(s) = [s, Y_1(s), 0, 1]^T

$$

where the function $$Y_1(s)$$ describes the profile contour, incorporating the hob’s addendum, dedendum, pressure angle, and tip radius. The series of cutting edges, indexed by an integer $$k$$ (with $$k=0$$ representing the central edge), are generated by rotating this axial profile around the hob axis with a helical pitch. The transformation for the $$k$$-th cutting edge is given by:

$$

L^1_k(s) = M^1_k \cdot P_1(s)

$$

with the transformation matrix $$M^1_k$$ accounting for the helical lead and the angular spacing between gashes:

$$

M^1_k =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & \frac{k P_a}{Z_L \tan \gamma_s} \\

0 & \cos(2\pi k / Z_L) & -\sin(2\pi k / Z_L) & 0 \\

0 & \sin(2\pi k / Z_L) & \cos(2\pi k / Z_L) & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

$$

Here, $$Z_L$$ is the number of gashes, $$P_a$$ is the axial pitch, and $$\gamma_s$$ is the lead angle (positive for a right-hand hob, negative for a left-hand hob).

Kinematic Model of the Hobbing Process

The relative motion between the rotating hob and the workpiece is complex. A series of coordinate systems are established to model this kinematics accurately, as conceptually illustrated in prior works. The key transformations involve:

- Hob Rotation: The hob rotates about its own axis ($$X_1$$).

- Hob Setting: The hob axis is tilted by the installation angle $$\gamma_i$$ relative to the workpiece axis and set at a center distance $$a$$, which for a gear with modification coefficient $$x$$ and module $$m_n$$ is $$a = r_g + r_h + x m_n$$, where $$r_g$$ and $$r_h$$ are the gear and hob pitch radii, respectively.

- Axial Feed: The hob translates along the workpiece axis ($$Z_4$$) with a feed rate $$f$$ (mm per revolution of the workpiece). The axial position $$\mu$$ is a function of the hob rotation angle $$\phi$$: $$\mu(\phi) = \pm \frac{N f \phi}{2\pi z}$$, where $$N$$ is the number of hob starts, $$z$$ is the gear tooth number, and the sign depends on climb or conventional hobbing.

- Workpiece Rotation: The workpiece rotates synchronously with the hob according to the gear ratio: $$\psi(\phi) = \pm \frac{N \phi}{z}$$.

The trajectory surface generated by the $$k$$-th cutting edge in the workpiece coordinate system $$O_5 – X_5Y_5Z_5$$ is obtained through a series of homogeneous coordinate transformations:

$$

G^g_k(s, \phi) = M^5_4 \cdot M^4_2 \cdot M^2_1 \cdot L^1_k(s)

$$

The matrices $$M^2_1$$, $$M^4_2$$, and $$M^5_4$$ represent the rotations and translations corresponding to hob rotation, hob setting with axial feed, and workpiece rotation, respectively. The family of surfaces generated by all active cutting edges envelops the theoretical machined tooth flank of the strain wave gear flexspline.

Theoretical Tooth Surface and Error Evaluation Model

The target geometry is the standard involute flank of a large-modified, straight spur gear. The tooth slot surface can be generated by translating its transverse involute profile along the gear axis. For a gear with base radius $$r_b$$, pressure angle $$\alpha_n$$, and modification coefficient $$x$$, the theoretical tooth slot surface for the $$i$$-th tooth space is parameterized by the involute roll angle $$\theta$$ and the face width coordinate $$w$$:

$$

F_i(\theta, w) =

\begin{bmatrix}

\pm [r_b \sin(\theta – \Omega – i\cdot\Delta) – r_b \theta \cos(\theta – \Omega – i\cdot\Delta)] \\

r_b \cos(\theta – \Omega – i\cdot\Delta) + r_b \theta \sin(\theta – \Omega – i\cdot\Delta) \\

w \\

1

\end{bmatrix}

$$

where $$\Omega$$ is a constant phase angle incorporating the tooth space symmetry and the effect of modification, and $$\Delta = 2\pi / z$$.

The surface normal vector $$n_i(\theta, w)$$ at any point is calculated from the cross product of the partial derivatives with respect to $$\theta$$ and $$w$$.

The core of the error evaluation lies in simulating the multi-edge cutting process. The theoretical tooth surface is discretized into a grid of points $$F_i(\theta_m, w_n)$$. For each point, the shortest distance along its normal vector $$n_i(\theta_m, w_n)$$ to any of the hob cutting edge trajectory surfaces $$G^g_k(s, \phi)$$ is computed. This minimum distance, signed relative to the normal direction, defines the theoretical machining error $$\delta_i(\theta_m, w_n)$$ at that point. A positive error indicates material remaining (undercut), while a negative error indicates overcut. By evaluating this for all grid points, the complete topological error map $$\delta_i(\theta, w)$$ for the tooth flank is constructed. Profile and lead error plots are derived from this map by fixing either the $$w$$ or $$\theta$$ parameter, respectively.

Experimental Validation of the Simulation Methodology

To verify the accuracy and reliability of the proposed simulation model, hobbing experiments were conducted on two test gears: a standard gear (modification $$x=0$$) and a large-modified gear ($$x=3$$). The key parameters are summarized below.

| Table 1: Workpiece Gear Parameters for Validation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gear | Module (mm) | Modification (x) | Pressure Angle | Number of Teeth | Tip Diameter (mm) |

| Gear 1 | 2.5 | 0 | 20° | 90 | 230.00 |

| Gear 2 (Large-Modified) | 2.5 | 3 | 20° | 90 | 245.00 |

| Table 2: Hob Parameters for Validation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Module (mm) | Pressure Angle | Number of Starts | Number of Gashes | Hand |

| 2.5 | 20° | 1 | 10 | Left |

The gears were machined on a CNC hobbing machine. The tooth flank errors of the manufactured gears were then meticulously measured using a coordinate measuring machine (CMM). The measured error values were compared directly with the simulation predictions from our model.

The results showed a strong correlation. For both the standard and the large-modified gear, the simulated profile error curves and lead error waveforms closely matched the trends and magnitudes of the experimentally measured data. The characteristic “waviness” of the lead error due to the intermittent axial feed was accurately predicted by the simulation. This close agreement validates the mathematical model’s capability to predict the theoretical machining errors inherent in the hobbing process for strain wave gear components, providing a reliable tool for further analysis.

Analysis of Hobbing Errors in Large-Modified Strain Wave Gear Flexsplines

With the validated model, we focus on the specific case of a typical strain wave gear flexspline. The parameters for this analysis are representative of common designs.

| Table 3: Flexspline Parameters for Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Module (mm) | Modification (x) | Pressure Angle | Number of Teeth | Tip Diameter (mm) | |

| 0.5 | 3 | 20° | 200 | 104.00 | |

| Table 4: Small-Module Hob Parameters for Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Module (mm) | Pressure Angle | Number of Starts | Number of Gashes | Hand |

| 0.5 | 20° | 1 | 12 | Left |

Simulating the hobbing process with a standard-length hob (73 active cutting edges) and a typical axial feed of $$f = 1.5 \text{ mm/rev}$$ reveals the characteristic error topology. The error map for a tooth flank shows two dominant features:

- Lead Error Waviness: A pronounced periodic error along the face width, corresponding to the hob’s axial feed rate.

- Profile Error Spikes: A significant increase in error magnitude near the tooth tip region of the profile.

While the lead error is common in hobbing, the profile error spike at the tip is particularly critical for large-modified gears and warrants detailed investigation.

Root Cause of Tip Region Error: Insufficient Cutting

The primary cause of the large error near the tooth tip in large-modified strain wave gear hobbing is insufficient cutting or lack of enveloping action by the available hob cutting edges. In hobbing a standard gear ($$x \approx 0$$), the central cutting edge ($$k=0$$) plays a major role in forming the final tooth profile. For a gear with many teeth, the involute flank near the pitch line is almost straight, and this central edge traces a path very close to the final form.

However, for a large-modified gear like the flexspline, the effective working portion of the tooth profile is shifted radially outward. The simulation reveals that the central cutting edge ($$k=0$$) does not engage the final tooth flank at all in the tip region. Instead, the left and right flanks are generated exclusively by cutting edges with negative and positive index numbers (e.g., $$k=-36$$ and $$k=36$$), respectively, which are far from the hob’s center. If the hob is not long enough, the most extreme active cutting edges cannot reach sufficiently “deep” into the tooth space to fully generate the profile all the way to the specified tip diameter. This results in an uncut (or undercut) region at the tooth tip, manifesting as a large positive error in our simulation. This is a fundamental geometric limitation when using a standard, finite-length hob on a high-modification coefficient strain wave gear component.

Solution: Determining the Minimum Hob Length

The solution is to use a longer hob with a greater number of active cutting edges. The minimum required hob length can be determined through simulation by identifying the highest cutting edge index needed to just contact the tooth tip point. For the analyzed flexspline, the required edge indices for complete generation of the tip points on left and right flanks are shown below.

| Table 5: Required Hob Cutting Edge Indices for Complete Tip Generation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter at Evaluation Point (mm) | 103.544 | 103.658 | 103.772 | 103.886 | 104.000 (Tip) |

| Left Flank (Edge Index k) | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 |

| Right Flank (Edge Index k) | -37 | -38 | -39 | -40 | -41 |

Table 5 indicates that to fully generate the tooth tip at 104.00 mm diameter, cutting edges with indices $$k=41$$ and $$k=-41$$ must be active. Therefore, the minimum total number of required active cutting edges is 83 (from -41 to +41, inclusive). Simulation confirms that using a hob with 83 active edges effectively eliminates the large tip error. The relationship between the required number of active edges and the modification coefficient $$x$$ for this class of strain wave gears is strongly positive and can be characterized to guide hob selection.

Optimizing Axial Feed to Minimize Lead Error

The lead error is a direct consequence of the discontinuous, stepwise axial advancement of the hob. The error reaches a maximum midway between two successive feed steps and a minimum at the step locations. This error is purely kinematic and can be significantly reduced by decreasing the axial feed per revolution $$f$$. The simulation clearly quantifies this effect. For the large-modified flexspline, reducing the feed from $$f = 1.5 \text{ mm/rev}$$ to $$f = 0.5 \text{ mm/rev}$$ resulted in a reduction of the peak-to-valley lead error by approximately 89%. The relationship between the maximum lead error magnitude $$\delta_{lead}^{max}$$ and the axial feed $$f$$ is central to process optimization for precision strain wave gear manufacturing.

Verification and Practical Implications for Strain Wave Gear Manufacturing

The proposed solutions were verified through comprehensive simulation of the strain wave gear flexspline case. When a sufficiently long hob (83 active edges) is employed, the severe profile error at the tip vanishes, as shown in comparative profile error plots. The remaining error distribution becomes more uniform and is dominated by the lead error pattern.

Subsequent reduction of the axial feed to $$f = 0.5 \text{ mm/rev}$$ further minimizes the overall tooth flank error. The combined strategy produces a simulated tooth surface where the maximum profile error is reduced to about 0.6 μm and the characteristic lead error waviness is drastically smoothed, achieving a level of theoretical precision suitable for high-performance strain wave gear assemblies.

The analysis yields a clear and actionable methodology for manufacturing large-modified strain wave gear flexsplines:

- Hob Length Selection: Prior to machining, determine the minimum required active hob length via simulation based on the specific gear parameters (module, pressure angle, tooth number, and most critically, the modification coefficient). For high-modification gears, a custom long hob may be necessary to avoid tip generation errors.

- Process Parameter Optimization: The axial feed rate $$f$$ should be minimized to the greatest extent economically feasible, as it has a direct and significant impact on reducing lead error. The trade-off is increased machining time.

- Error Prediction and Compensation: The established model can serve as a virtual metrology tool, predicting the theoretical error map for a given set of tool and process parameters. This information can be used to assess manufacturability or even as a basis for active error compensation strategies in advanced CNC hobbing machines.

In conclusion, the precision hobbing of large-modified components, such as the flexspline in a strain wave gear drive, requires special consideration beyond standard gear practice. The primary challenges are the geometric limitation of insufficient cutting at the tooth tip with standard hob lengths and the kinematic error induced by axial feed. Through rigorous mathematical modeling and simulation, these errors can be accurately predicted, analyzed, and effectively mitigated by selecting an adequately long hob and employing a reduced axial feed rate. This systematic approach is essential for realizing the full potential of strain wave gear technology in applications demanding the highest levels of accuracy and reliability.