The pursuit of higher efficiency and reliability in power transmission continuously drives innovation in gear design. Among various gear types, the traditional worm gear drive is often associated with significant sliding friction, leading to relatively low transmission efficiency and pronounced thermal challenges. To address these inherent limitations, the single roller enveloping face worm gear drive has been proposed as a novel configuration. This design fundamentally alters the worm wheel by replacing its conventional teeth with cylindrical rollers that are free to rotate about their own axes. This paper presents a comprehensive, first-principles analysis of this drive, focusing on the detailed characteristics of the contact lines on the roller surface, the self-rotation kinematics of the rollers, and the consequential impact on sliding velocities. The objective is to establish a robust theoretical foundation for evaluating its contact performance and anti-friction potential.

1. Fundamentals and Mathematical Modeling of the Worm Gear Drive

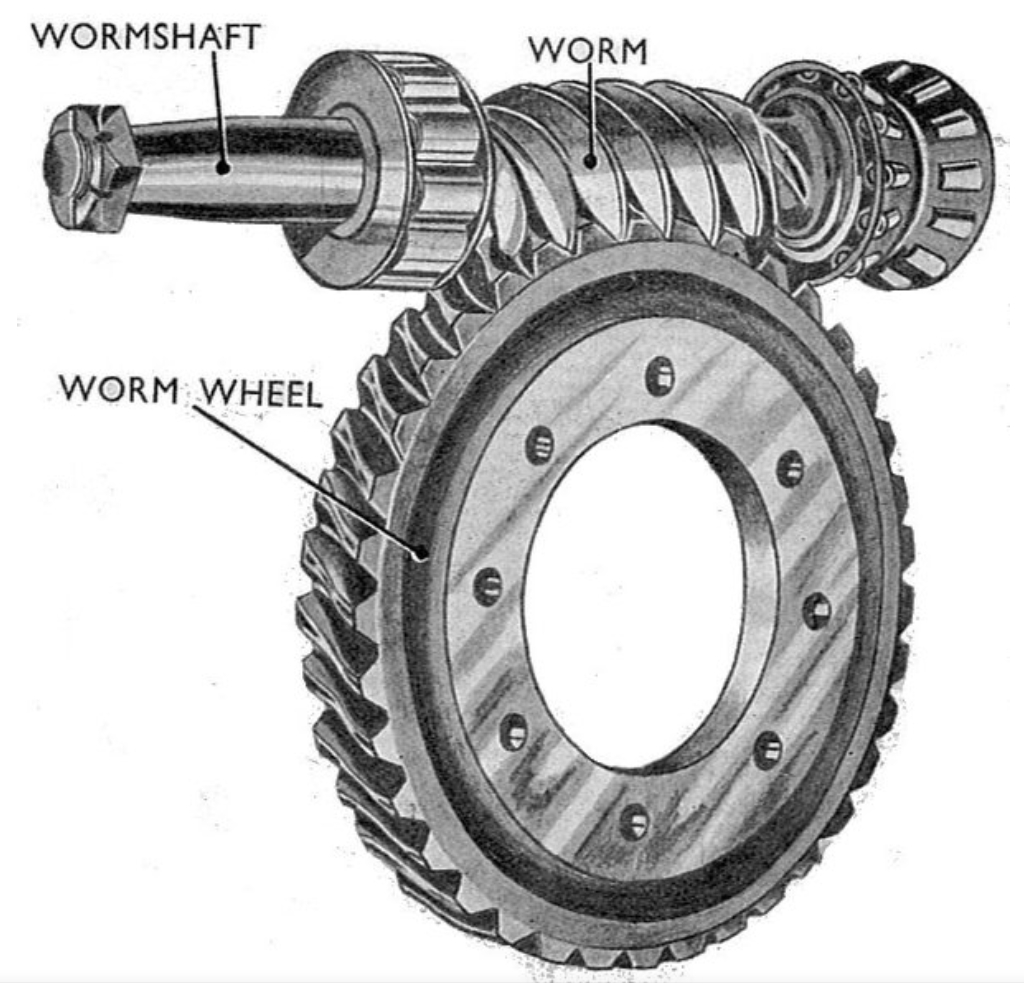

The formation of the conjugate tooth surfaces in the single roller enveloping face worm gear drive is based on the theory of gearing. The analysis begins with the establishment of coordinate systems to describe the spatial relationship and motion between the worm and the worm wheel (roller assembly).

1.1 Establishment of Coordinate Systems and Moving Frame

Figure 1 illustrates the coordinate systems essential for defining the worm gear drive geometry and kinematics. The fixed coordinate systems are denoted as $\sigma_1(\mathbf{i}_1, \mathbf{j}_1, \mathbf{k}_1)$ and $\sigma_2(\mathbf{i}_2, \mathbf{j}_2, \mathbf{k}_2)$. The moving coordinate systems rigidly attached to the worm and the worm wheel are $\sigma_1′(\mathbf{i}_1′, \mathbf{j}_1′, \mathbf{k}_1′)$ and $\sigma_2′(\mathbf{i}_2′, \mathbf{j}_2′, \mathbf{k}_2′)$, respectively. The axes $\mathbf{k}_1’$ and $\mathbf{k}_2’$ represent the rotation axes of the worm and the worm wheel, with angular velocity vectors $\boldsymbol{\omega}_1$ and $\boldsymbol{\omega}_2$. The transmission ratio is defined as $i_{12} = \omega_1 / \omega_2 = Z_2 / Z_1$, where $Z_1$ is the number of worm threads and $Z_2$ is the number of rollers on the worm wheel. The center distance is $A$.

The cylindrical roller, representing a tooth of the worm wheel, can rotate about its own axis. A local coordinate system $\sigma_0(\mathbf{i}_0, \mathbf{j}_0, \mathbf{k}_0)$ is fixed to the worm wheel at the center of the roller’s top face, with the $\mathbf{k}_0$-axis aligned along the roller’s axis (radial direction of the worm wheel) and perpendicular to $\mathbf{k}_2’$. The angular displacements of the worm and worm wheel are $\varphi_1$ and $\varphi_2$, related by $\varphi_1 = i_{12} \varphi_2$.

At the point of contact $O_p$, a moving frame $\sigma_p(\mathbf{e}_1, \mathbf{e}_2, \mathbf{n})$ is established on the roller surface, as shown in Figure 2. Here, $\mathbf{n}$ is the unit normal vector to the surface at $O_p$, and $\mathbf{e}_1$ and $\mathbf{e}_2$ are orthogonal unit vectors in the tangent plane. Crucially, the roller’s axis of self-rotation is aligned with the $\mathbf{e}_2$ direction.

1.2 Meshing Equation and Tooth Surface Equation

The fundamental condition for contact between two conjugate surfaces is that their relative velocity at the contact point has no component along the common normal direction. This is expressed by the meshing equation:

$$

\boldsymbol{V}^{(1’2′)} \cdot \mathbf{n} = 0

$$

where $\boldsymbol{V}^{(1’2′)}$ is the relative velocity vector at the contact point between the worm surface ($\Sigma_1$) and the roller surface ($\Sigma_2$). This vector can be derived from kinematic relations. Based on the coordinate systems and applying transformation matrices, the detailed meshing function for this specific worm gear drive is obtained. The component of the relative velocity along the normal direction in the moving frame is found to be:

$$

V_n^{(1’2′)} = M_1 \cos\varphi_2 + M_2 \sin\varphi_2 + M_3

$$

where the coefficients $M_1, M_2, M_3$ are functions of the roller surface parameters and design constants. The meshing condition $V_n^{(1’2′)} = 0$ therefore establishes a functional relationship between the worm wheel rotation angle $\varphi_2$ and the roller surface parameters.

The roller is a cylinder. Let $u$ be the height parameter along the roller axis ($\mathbf{k}_0$ direction) and $\theta$ be the angular parameter around the roller axis. The surface of the roller can be represented in $\sigma_0$ as:

$$

\mathbf{r}_0 = R\cos\theta \, \mathbf{i}_0 + R\sin\theta \, \mathbf{j}_0 + u \, \mathbf{k}_0

$$

where $R$ is the roller radius. The meshing equation, when solved, provides a constraint linking $u$, $\theta$, and $\varphi_2$:

$$

u = f(\theta, \varphi_2) \quad \text{or} \quad \theta = g(u, \varphi_2)

$$

For a given instant (fixed $\varphi_2$), the set of $(u, \theta)$ points satisfying this equation defines the instantaneous contact line on the roller surface. The corresponding worm tooth surface $\mathbf{r}_{1′}(u, \theta, \varphi_1)$ is generated by applying the sequence of coordinate transformations from $\sigma_0$ to $\sigma_1’$, incorporating the meshing condition.

2. Analysis of Contact Lines on the Roller

The nature of the contact lines on the roller surface is critical for understanding load distribution, wear patterns, and the self-rotation behavior of the roller within the worm gear drive.

2.1 Geometry and Length of Instantaneous Contact Lines

The parametric equation for an instantaneous contact line on the roller, for a fixed $\varphi_2$, is given by combining the roller surface equation with the meshing condition $u = f(\theta, \varphi_2)$:

$$

\mathbf{r}_0(\theta) = R\cos\theta \, \mathbf{i}_0 + R\sin\theta \, \mathbf{j}_0 + f(\theta, \varphi_2) \, \mathbf{k}_0, \quad \theta \in [\theta_1, \theta_2]

$$

The length $L_i$ of the $i$-th contact line (corresponding to a specific $\varphi_2^{(i)}$) is calculated by integrating the differential arc length along this space curve:

$$

L_i = \int_{\theta_{i1}}^{\theta_{i2}} \sqrt{ \left( \frac{dx_0}{d\theta} \right)^2 + \left( \frac{dy_0}{d\theta} \right)^2 + \left( \frac{dz_0}{d\theta} \right)^2 } \, d\theta = \int_{\theta_{i1}}^{\theta_{i2}} \sqrt{ R^2 + \left( \frac{df(\theta, \varphi_2^{(i)})}{d\theta} \right)^2 } \, d\theta

$$

where $\theta_{i1}$ and $\theta_{i2}$ are the lower and upper bounds of $\theta$ for that particular contact line.

2.2 Contact Line Wrap Angle and Density

To quantitatively describe the spatial characteristics of contact in this worm gear drive, two new metrics are introduced: Contact Line Wrap Angle ($\lambda$) and Contact Line Density ($\epsilon$).

Wrap Angle ($\lambda$): This is defined as the central angle subtended by the projection of a single instantaneous contact line onto the plane of the roller’s base. It measures the angular spread of the contact line around the roller’s circumference. A larger $\lambda$ indicates a more spatially extended contact line, potentially implying a more complex contact stress state. For a given $\varphi_2$, the wrap angle is simply the range of the $\theta$ parameter for that line:

$$

\lambda_i = \theta_{i2} – \theta_{i1}

$$

Contact Line Density ($\epsilon$): This concept describes how densely the family of contact lines (from different $\varphi_2$ positions) is distributed over the roller’s surface. It is defined as the incremental change in the worm wheel angle $\varphi_2$ per unit change in the roller’s angular parameter $\theta$ for a constant roller height $u$:

$$

\epsilon = \left| \frac{\partial \varphi_2(u, \theta)}{\partial \theta} \right|

$$

A higher $\epsilon$ means a larger change in $\varphi_2$ is needed to shift the contact line by a small amount in $\theta$, implying the contact lines are sparsely distributed in that region of the roller surface. Conversely, a low $\epsilon$ indicates closely spaced contact lines.

2.3 Numerical Analysis of Contact Line Parameters

A numerical analysis is performed using the following primary geometrical parameters for the worm gear drive:

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Center Distance | $A$ | 160 mm |

| Number of Worm Threads | $Z_1$ | 1 |

| Number of Rollers (Teeth) | $Z_2$ | 25 |

| Roller Radius | $R$ | 9 mm |

| Worm Angular Velocity | $\omega_1$ | 1 rad/s |

The analysis yields the following key insights into the contact behavior of this worm gear drive:

Spatial Distribution: The instantaneous contact lines on the roller surface vary with $\varphi_2$. During the meshing cycle, the contact lines shift, and their distribution changes from being relatively dense at the start (roller entry) to more sparse towards the end (roller exit). Figure 6 visualizes this spatial distribution in the roller’s coordinate system $\sigma_0$.

Contact Line Length ($L_i$): Figure 7 plots the contact line length against the worm wheel angle $\varphi_2$. The length variation is remarkably small, with a total change of only about 0.0015 mm over the entire mesh cycle. The curve is mostly flat for the first two-thirds of the cycle, followed by a slightly steeper increase in the final third. The smoothness of the curve indicates stable meshing without abrupt changes.

Wrap Angle ($\lambda$): As shown in Figure 8, the wrap angle follows a trend similar to the contact line length, which is expected given their geometric relation. The values are very small, ranging from approximately 0.1° to 1.3°. This indicates that each instantaneous contact line occupies only a very narrow strip on the roller’s circumference.

Contact Line Density ($\epsilon$): Figure 9 shows the contact line density $\epsilon$ versus $\varphi_2$ for three different roller heights: near the tooth tip ($u$ small), middle, and root ($u$ large). The density is highest at the tip and decreases towards the root. All curves show a rapid decline in density as meshing progresses, meaning contact lines become increasingly spaced apart on the roller surface later in the engagement.

Total Contact Area on Roller: By defining the region on the unwrapped roller surface bounded by the first and last contact lines (entry and exit) and the roller’s top and bottom edges, the total area $D$ where contact occurs during a full mesh cycle can be calculated. For the given parameters, this area is found to be:

$$

D = \int_{y_1}^{y_2} [x_c(y) – x_d(y)] \, dy \approx 8.148 \, \text{mm}^2

$$

where $x_c(y)$ and $x_d(y)$ describe the entry and exit contact lines in the unwrapped coordinates. This area represents only about 0.88% of the total cylindrical surface area of the roller. This extreme localization of the contact zone has significant implications for wear and contact fatigue life in the worm gear drive.

3. Self-Rotation Kinematics of the Roller

The defining feature of this worm gear drive is the ability of the roller to spin freely about its own axis. This self-rotation is crucial for converting sliding friction into rolling friction, thereby enhancing efficiency.

3.1 Self-Rotation Angle

The self-rotation angle $\mu$ is defined as the acute angle between the relative velocity vector $\boldsymbol{V}^{(1’2′)}$ at the contact point and the roller’s own axis (which is aligned with $\mathbf{e}_2$). Since $\boldsymbol{V}^{(1’2′)}$ lies in the common tangent plane ($\mathbf{n}$ component is zero due to meshing equation), its direction within that plane determines how effectively it drives roller rotation. The component $V_1^{(1’2′)}$ along $\mathbf{e}_1$ is tangential to the roller and causes it to rotate, while the component $V_2^{(1’2′)}$ along $\mathbf{e}_2$ represents pure sliding. Therefore, an ideal self-rotation angle $\mu$ close to 90° indicates that most of the relative motion is converted into rolling.

The self-rotation angle is calculated as:

$$

\mu = \arccos\left( \frac{ |V_2^{(1’2′)}| }{ ||\boldsymbol{V}^{(1’2′)}|| } \right) = \arccos\left( \frac{ |V_2^{(1’2′)}| }{ \sqrt{ (V_1^{(1’2′)})^2 + (V_2^{(1’2′)})^2 } } \right)

$$

Figure 12 shows $\mu$ as a function of roller height $u$ for various $\varphi_2$. Critically, across almost the entire mesh cycle and for all roller heights, the self-rotation angle remains above 89°. This demonstrates the excellent inherent self-rotation potential of the roller in this worm gear drive configuration.

3.2 Self-Rotation Angular Velocity and Total Rotation

The instantaneous self-rotation angular velocity $\omega_0$ of the roller is derived from the tangential component of the relative velocity that induces rolling. The rolling condition at the contact point gives:

$$

\omega_0 R = V_1^{(1’2′)}

$$

Therefore,

$$

\omega_0(u, \theta, \varphi_2) = \frac{V_1^{(1’2′)}(u, \theta, \varphi_2)}{R}

$$

Using the meshing condition $\theta = g(u, \varphi_2)$, $\omega_0$ can be expressed as a function of $u$ and $\varphi_2$.

Analysis of $\omega_0$: Figure 13 plots $\omega_0$ against $\varphi_2$ for different $u$. The angular velocity is highest (27.5-30 rad/s) at the start of engagement and decreases to about 7.5 rad/s by the end. Figure 14 shows $\omega_0$ versus $u$ for different $\varphi_2$, revealing a complex but generally mild dependence on roller height.

To obtain a single representative value for the self-rotation speed at a given meshing position, the height-averaged self-rotation angular velocity $\bar{\omega}_{0u}$ is introduced:

$$

\bar{\omega}_{0u}(\varphi_2) = \frac{1}{u_2 – u_1} \int_{u_1}^{u_2} \omega_0(u, \varphi_2) \, du

$$

where $u_1$ and $u_2$ define the active height of the roller in contact.

Total Rotation per Mesh Cycle: The total angle $\Theta_{total}$ through which a roller turns about its own axis during one complete engagement cycle is a key performance metric. It is obtained by integrating the averaged angular velocity over the meshing time $T$:

$$

\Theta_{total} = \int_{0}^{T} \bar{\omega}_{0u}(\varphi_2(t)) \, dt = \int_{\varphi_{2i}}^{\varphi_{2e}} \frac{\bar{\omega}_{0u}(\varphi_2)}{\omega_2} \, d\varphi_2

$$

where $\varphi_{2i}$ and $\varphi_{2e}$ are the initial and final worm wheel angles for the roller’s mesh cycle, and $\omega_2 = \omega_1 / i_{12}$ is the worm wheel angular velocity.

Performing this numerical integration for the example worm gear drive yields a remarkable result:

$$

\Theta_{total} \approx 749.85 \, \text{rad} \quad \text{or} \quad \approx 119.34 \, \text{revolutions}

$$

This implies that during a single pass through the mesh, each roller spins over 119 times about its own axis. This intense self-rotation is a direct consequence of the near-90° self-rotation angle and is fundamental to the worm gear drive’s anti-friction mechanism.

4. Analysis of Sliding Velocity and Anti-Slip Effect

The primary benefit of the roller’s self-rotation is the reduction of sliding velocity between the contacting surfaces. This section compares the sliding velocity in the proposed design (free roller) with that in a hypothetical case where the roller is fixed (cannot rotate).

4.1 Sliding Velocity with Free Roller (Design Condition)

When the roller is free to rotate, the relative velocity component $V_1^{(1’2′)}$ is accommodated as rolling motion. Therefore, the only source of sliding is the component $V_2^{(1’2′)}$ along the roller’s axis. The sliding velocity vector is:

$$

\boldsymbol{V}_{h,\text{free}} = V_2^{(1’2′)} \, \mathbf{e}_2

$$

and its magnitude is $|V_2^{(1’2′)}|$. For the example worm gear drive, this magnitude is calculated and plotted in Figures 15 and 16. The sliding velocity remains extremely low, varying between approximately 0.2 mm/s and 0.95 mm/s throughout the mesh cycle.

4.2 Sliding Velocity with Fixed Roller (Comparison Baseline)

If the roller were fixed (a conventional, non-rotating tooth), none of the relative velocity would be converted to roll. The entire relative velocity vector in the tangent plane would constitute sliding:

$$

\boldsymbol{V}_{h,\text{fixed}} = V_1^{(1’2′)} \, \mathbf{e}_1 + V_2^{(1’2′)} \, \mathbf{e}_2

$$

Its magnitude is $||\boldsymbol{V}_{h,\text{fixed}}|| = \sqrt{(V_1^{(1’2′)})^2 + (V_2^{(1’2′)})^2}$. Figures 17 and 18 show this magnitude for the same operating conditions. The sliding velocity in this case is orders of magnitude higher, ranging from about 55 mm/s to 265 mm/s.

4.3 Comparative Summary

The contrast is stark. The maximum sliding velocity in the free-roller worm gear drive is less than 0.36% of the minimum sliding velocity in the fixed-roller case. This dramatic reduction, by a factor of over 275, highlights the exceptional anti-sliding efficacy of the single roller enveloping face worm gear drive design. The near-elimination of sliding friction is the key to its potential for high efficiency and low thermal loading.

| Condition | Sliding Velocity Range | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Free Roller (Proposed Design) | 0.2 – 0.95 mm/s | Extremely low, primarily axial sliding. |

| Fixed Roller (Conventional) | 55 – 265 mm/s | High, combined tangential and axial sliding. |

5. Conclusion

This comprehensive analysis of the single roller enveloping face worm gear drive provides profound insights into its unique meshing behavior. The introduction and numerical evaluation of the contact line wrap angle ($\lambda$) and density ($\epsilon$) quantitatively describe the sparse and highly localized nature of the contact pattern on the roller surface, with the total contact zone covering less than 1% of the roller’s area. The kinematic analysis reveals that the rollers possess an excellent self-rotation capability, evidenced by self-rotation angles consistently above 89°. Consequently, each roller undergoes approximately 119 full revolutions about its own axis during a single meshing engagement with the worm. The most significant outcome is the drastic reduction in sliding velocity. Compared to a configuration with fixed rollers, the operational sliding velocity in this worm gear drive is reduced to a mere fraction (less than 0.36%), effectively transforming sliding friction into rolling friction. These characteristics—minimal contact area, intense self-rotation, and near-elimination of sliding—establish a strong theoretical foundation for this worm gear drive as a high-efficiency, low-wear alternative to traditional worm gear designs, meriting further investigation into its load capacity and fatigue performance.